Updated: September 2018

In order to effectively manage human impacts on marine mammals, we need to know how many marine mammals are in the management area and if this number is changing over time: is the population going up or down? The best way to get this information is to carry out surveys to estimate the abundance of whales or seals in specific areas. Repeating surveys over time helps to determine if the population is stable, rising or falling.

Why do we count seals?

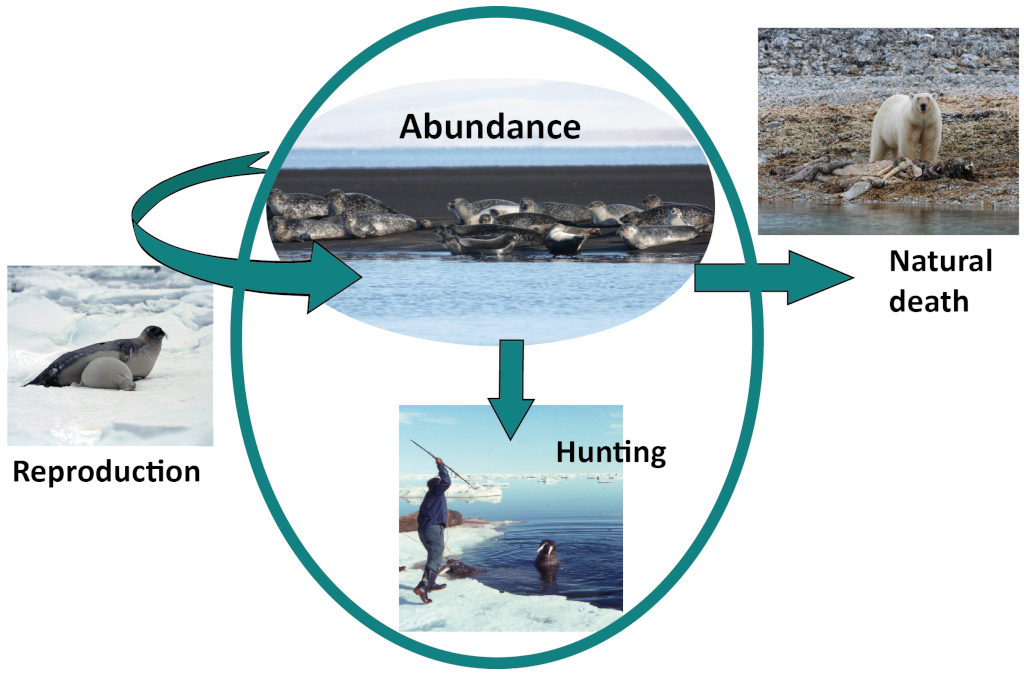

The future abundance of animals depends on several factors. Wildlife managers usually have knowledge of only abundance and catch.

Researchers conduct surveys to generate estimates of absolute abundance, which consequently represents the number of animals present in a specific area at a specific time. In some cases estimates of relative abundance (a fraction of absolute abundance that is assumed to be constant) are also useful. By conducting repeated surveys over time, it becomes possible to estimate trends in abundance, thereby determining whether the number of animals is increasing, decreasing, or remaining stable over time. The main use of these estimates is for the management of whale and seal populations. Additionally, surveys serve the purpose of general environmental monitoring and ecosystem research.

Marine Mammal Management

“Management” does not mean telling seals what to do! It is actually the management of human impacts on seal populations, mainly direct catch (hunting) and indirect catch (by-catch, ship strikes), but also other sub-lethal impacts such as pollution and climate change. The main goal of management is usually to ensure that human impacts on marine mammal populations are sustainable, thus meaning that they do not cause the populations to decrease below a pre-defined threshold. To accomplish this, researchers combine estimates of abundance with past, present, and projected future catch levels in a population model. The population model is a mathematical model that replicates the population’s response to catch. This enables managers to set allowable total removal levels: levels of direct and/or indirect catch that will not endanger the population.

How do we count seals?

Counting pinnipeds and cetaceans differs in approach. For estimating the total population, researchers count both adult seals and pups, typically during the whelping or moulting seasons when the seals gather on land or ice. In fact, the counting methods vary depending on the species and location. Different seal species have different whelping and moulting times, and this can even vary within species, depending on location.

Which type of count?

Pup production surveys

Pups are counted at breeding colonies to estimate pup production. The pup production and factors like female fecundity, mortality and catch rates inform a population model to estimate the total population size. Grey and harp seals are among the species for which the population size is based on pup production surveys.

Moulting surveys

Seals are counted during the moulting season, when most of the population is hauled out on land or ice and thus available for counting. Different age classes usually start moulting at different times, so surveys take place multiple times throughout the moulting period, or when the highest proportion of seals are hauled out. Correction factors account for the portion of seals not present on land or ice and therefore not available for counting. Harbour and ringed seals are among the species for which the estimation of the population size uses counts during the moulting season.

Ships versus air

Several methods can be employed to conduct aerial surveys. Observers can count seals directly from a plane, and/or photographed from an airplane, with counts performed on the photographs. Lately, it has also become possible to use drones/unmanned aerial vehicles (UVAs) to photograph seals. This is both safer, less expensive, and more environmentally friendly than using airplanes.

In shipboard or land-based surveys, observers count hauled-out seals from ships or nearby islets. This can be difficult because of the angle, as seals can hide behind each other or in the back, thus missed by the observers. The Institute of Marine Research (IMR) in Norway has had success combining this survey method with drone footage for harbour seal counts, especially when there are many seals on each site (IMR 2016).

Successful surveys; land-based, shipboard and aerial, are heavily dependent on good weather and sighting conditions.

Ice seals are those seal species who complete their life-cycles largely on or about the sea ice: harp, hooded, ringed and bearded seals in the North Atlantic/Arctic. Directly counting the seals is extremely challenging due to their wide distribution and dispersion across the North Atlantic and Arctic Oceans for most of the year. Also they spend much of their time underwater. Methods to estimate the population sizes of ice seal species usually use some combination of direct counts and population modelling to obtain the total number of seals.

Harp and hooded seals

Harp and hooded seals congregate during the whelping season, which makes counting them possible at that period. However, not all of the population is present at the surface at any one time or place. Therefore, direct surveys of the whelping grounds (counting seal pups on the ice) are used in combination with population modelling.

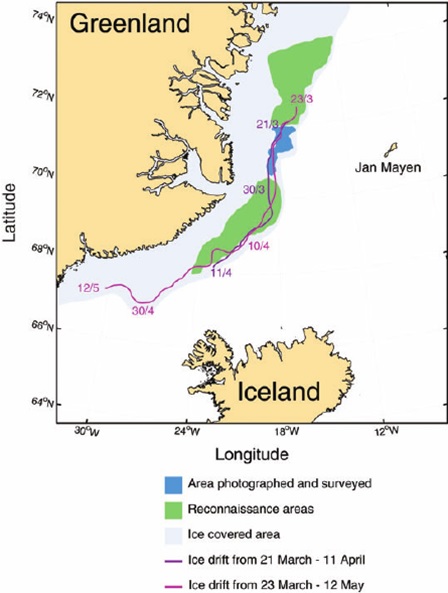

In general, surveys for harp and hooded seals use a combination of visual and photographic methods (Hammill et al. 2014, 2015, Øigard et al. 2014). Visual reconnaissance surveys, using helicopters and fixed wing aircraft, locate and map the whelping patches. Photographic survey transects are then flown over the patches. Experienced readers count the seal pups in the photos, and the counts undergo verification through repeated readings. The pups are classified by “stages” according to their apparent age, from newborn to weaned pup. The combination of these data, along with information obtained from tagged pups, enables the estimation of the proportion of pups present on the ice rather than in the water, making them “visible” at any given time. The corrected pup density on the photographic transects are applied to the entire survey area using standard strip transect methodology.

Population models use the pup production to estimate the total population. These models incorporate data on pregnancy rate at age, natural mortality rate and catch at age to calculate the number of adult seals needed to produce the number of pups observed during the survey (Hammill et al. 2014, 2015, Øigard et al. 2014).

Ringed Seals

A dog sniffing out a ringed seal lair during counts of ringed seals in Alaska. © University of Southeast Alaska

Ringed seals spread throughout the Arctic but a total population count throughout their range does not exist. However, ringed seal abundance estimates exist for various areas using many different methods: 1) direct counts from a ship or from land, 2) acoustic monitoring (estimating the number of seals based on number of recorded vocalizations), 3) estimating how big the population size must be to sustain the polar bear populations, 4) using dogs to find breeding lairs and counting the lairs, 5) looking at the type of sea ice that ringed seals typically use and then using known sea ice density to estimate ringed seal numbers, and 5) the most common method of using aerial surveys, similar to harp and hooded seals.

Rather than during the breeding period (when ringed seals are hiding in their “birth lairs”), counting takes place during the moulting period (when seals lose their hair and grow a new coat), as the most seals are then on the ice. Airplanes are flown over concentrations of seals and photographs are taken. Information from tagged seals are used to estimate how many seals were likely not counted because they were in the water and not available to be photographed.

Bearded Seals

Similar to ringed seals, bearded seals occur throughout the Arctic, and a total population estimate does not exist. However, some aerial surveys have been conducted in some areas, and ice density has also been used to estimate population size. For the ice density estimation, aerial surveys were conducted in various areas, and the average density of seals on various types of ice (e.g. fast ice versus pack ice) were documented. Then, using satellite maps of ice density, the number of bearded seals was estimated.

Coastal seals are seal species for which the life cycle is not obligatory associated with ice. Coastal seals; harbour and grey seals in the North Atlantic, are counted by visual and photographic methods during either the pupping season or the annual moult when most of the population haul out on land. In Norway, coastal seal surveys cover only specific sections of the coastline each year, resulting in a complete count of coastal seals approximately every fifth year (Nilssen and Haug 2007, Nilssen et al 2010).

Grey seals

Pup production surveys provide estimates for the total population of grey seals. In Norway, researchers use mainly shipboard and land-based surveys, and sometimes also aerial photographic surveys to count pups. During the grey seal pupping season, each pupping area undergoes two or three counts to ensure comprehensive coverage (Nilssen and Haug 2007). To prevent double-counting of pups on subsequent surveys, the researchers record the developmental stage of each pup (Nilssen and Haug 2007). Then researchers estimate the total population using population modeling techniques (Øigård et al. 2012). In Iceland, grey seal pup counts primarily rely on aerial surveys, supported by shipboard and land-based surveys (CSWG 2016, Hauksson et al. 2014).

Harbour seals

Harbour seal population investigations along the Norwegian coast began with interviews and questionnaires in the 1960s (Øynes 1964, 1966, cited in Nilssen et al. 2010).

Boat-based counts in the breeding season were conducted later. At present, researchers conduct aerial photographic surveys (using fixed-wing aircraft and drones) to count harbour seals during the moulting season. In areas with challenging topography or low seal numbers, visual counts with binoculars from boats and land serve as a supplement. (Nilssen et al. 2010, IMR 2016).

Since 1980, researchers in Iceland have been conducting aerial population surveys of harbour seals using both photography and direct counts. Two observers count and photograph all observed seals. The surveys follow standardized conditions and take place during the peak of the moulting season, utilizing haul-out sites from previous surveys (Þorbjörnsson et al. 2017). Icelandic harbour seals mostly haul out in smaller groups of <4 animals, meaning that the entire coastline needs surveying in order to obtain an accurate population estimate (Þorbjörnsson et al. 2017). Covering a significant coastline within a limited time frame (approximately 3 weeks) has been challenging during the aerial surveys of harbour seals in Iceland. Additionally, the unfavorable weather conditions often result in only a few feasible days for airborne operations (CSWG 2016).

The optimization of correction factors for Icelandic conditions is still underway. However, using similar correction factors for all years ensures that the yearly results are comparable across different years (Þorbjörnsson et al. 2017) and represent an index of relative abundance.

(CSWG) Report of the Coastal Seals Working Group (2016) Reykjavik, Iceland. Available at: https://nammco.no/topics/sc-working-group-reports/

Hammill, M.O., Stenson, G.B., Mosnier A., and Doniol-Valcroze, T. (2014). Abundance Estimates of Northwest Atlantic Harp seals and Management advice for 2014. DFO Can. Sci. Advis. Sec. Res. Doc. 2014/022. v + 33 p.

Hammill, M.O., Stenson, G.B., Doniol-Valcroze, T., Mosnier, A., 2015. Conservation of northwest Atlantic harp seals: past success, future uncertainty? Biol. Conserv. 192, 181–191 Hauksson, E., Ólafsson, H. G. and Granquist, S. (2014). Talning útselskópa úr lofti haustið 2012. Available at: http://gamli.veidimal.is/default.asp?sid_id=23836&tre_rod=003%7C002%7C&tId=15&meira=1&sky_id=19573

IMR (2016). Omfattende telling av sel i sør, Institute of Marine Research [online] Available at: https://www.hi.no/nyhetsarkiv/2016/september/omfattende_telling_av_sel_i_sor/nb-no [Accessed 27 June 2018]

Nilssen, K.T. and Haug, T. (2007). Status of grey seals (Halichoerus grypus) in Norway. NAMMCO Sci. Publ. 6:23-31

Nilssen, K.T., Skavberg, N.-E., Poltermann, M., Haug, T., Härkönen, T., and Henriksen, G. (2010). Status of harbour seals (Phoca vitulina) in mainland Norway. NAMMCO Sci. Publ. 8:61-70

Þorbjörnsson, J. G., Hauksson, E., Sigurðsson, G. M. and Granquist, S. M. (2017), Aerial census of the Icelandic harbour seal (Phoca vitulina) population in 2016: Population estimate, trends and current status. Available at: https://www.hafogvatn.is/is/midlun/utgafa/haf-og-vatnarannsoknir/aerial-census-of-the-icelandic-harbour-seal-phoca-vitulina-population-in-2016-population-estimate-trends-and-current-status-landselstalning-2016-stofnstaerdarmat-sveiflur-og-astand-stofns

Øigård, T. A., Haug, T., and Nilssen, K. T. (2014). From pup production to quotas: current status of harp seals in the Greenland Sea. – ICES Journal of Marine Science, 71: 537–545.

Øigård, T.A., Frie, A.K., Nilssen, K.T. & Hammill, M.O. 2012. Modelling the abundance of grey seals (Halichoerus gryupus) along the Norwegian coast. ICES Journal of Marine Science 69: 1446-1447. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fss013