Grey seal

Updated: July 2023

The grey seal (Halichoerus grypus) is a coastal or continental shelf marine mammal species, inhabiting the temperate areas of the North Atlantic. Grey seals haul out on exposed reefs or on beaches of undisturbed islands. They are relatively large, around 2 m in length and 200–400 kg in weight, with males larger than females. In addition to the difference in size between the sexes, there are differences in shape as well. Adult males have elongated snouts with a convex outline giving it an appearance like a horse head. The body colour of the adults may vary from entirely black to almost creamy-white, with males tending to be darker than females.

ABUNDANCE

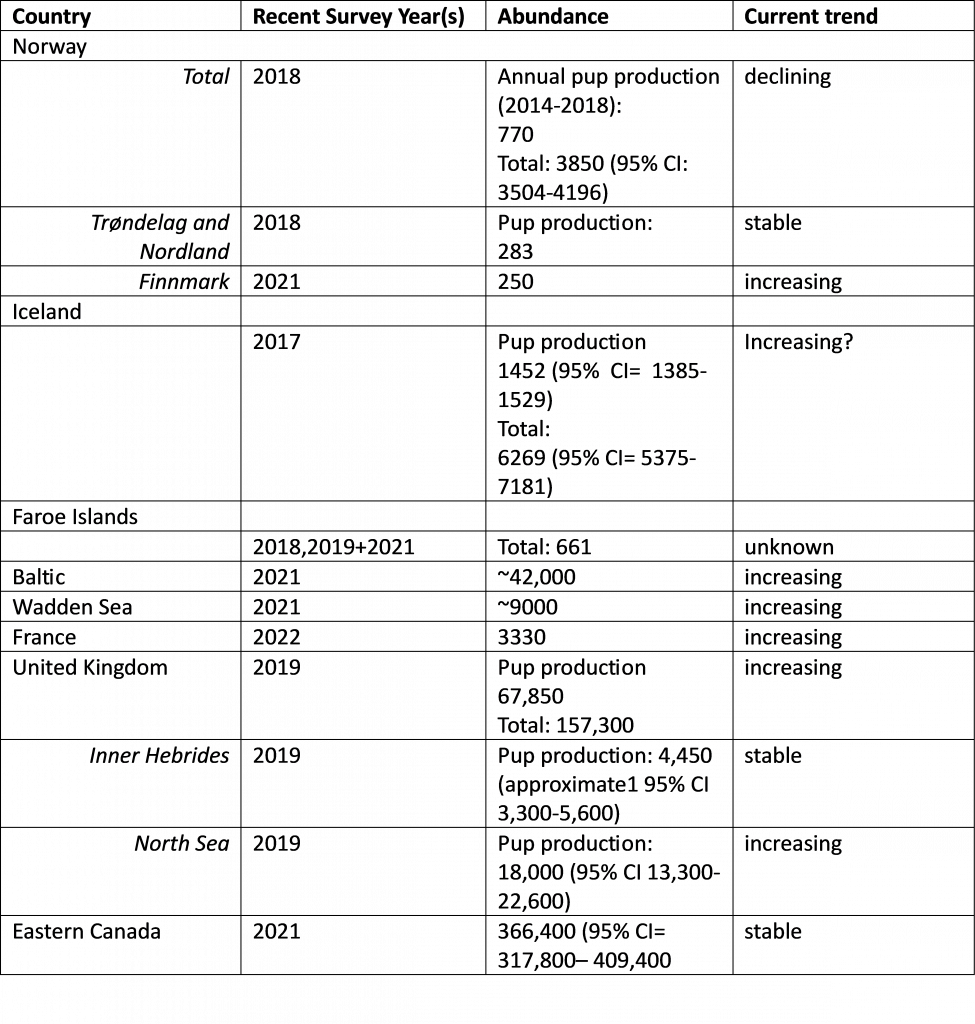

There are estimated to be approximately 650,000 grey seals globally in the North Atlantic and Baltic, with the largest numbers found on the east coasts of Canada and the USA.

DISTRIBUTION

Grey seals inhabit temperate waters of the North Atlantic but only some individuals have been observed in southern Greenland, likely as visitors.

RELATION TO HUMANS

In the NAMMCO countries, small numbers of grey seals are hunted, mainly in Norway. This is primarily for their meat but in previous years also some fat whitecoats were taken, mainly for the blubber.

CONSERVATION AND MANAGEMENT

The NAMMCO Coastal Seals Working Group provides scientific advice on stock status and sustainable takes, although management actions are the responsibility of the member countries.

In the most recent assessment (2016) the global IUCN Red List as well as the Norwegian national red list register the species as ‘Least Concern’. It is listed as ‘Vulnerable’ on the Icelandic national red list as of 2018 because of a decreasing population over the last decades.

.

Lifespan

35-40 years

Productivity

One pup per year, age at maturity 5-7 years

Feeding

Generalists feeding on a wide variety of prey usually near the sea bottom (demersal and benthic fish)

Size

2m in length and 200-400kg in weight, with males larger than females

General Characteristics

The grey seal is a coastal seal and occurs on both shores of the North Atlantic Ocean and the Baltic Sea. In Latin Halichoerus grypus means “hook-nosed sea pig”. It is a large seal of the family Phocidae, which are commonly referred to as “true seals” or “earless seals”. It is the only species classified in the genus Halichoerus.

They are relatively large, around 2 m in length and 200–400 kg in weight, with males larger than females. In addition to the difference in size between the sexes, there are differences in shape as well. The snout of the adult male is elongated with a convex outline giving it an appearance like a horse head. The body colour of the adults may vary from entirely black to almost creamy-white, with males tending to be darker than females.

The grey seal is a relatively large phocid seal with a cold temperate to sub-Arctic distribution along the coasts of the North Atlantic Ocean (Hauget al., 2007).

There are two recognized subspecies of this seal (Berta & Churchill, 2012):

Halichoerus grypus grypus (Fabricius 1791) – Atlantic grey seal

Distribution: Northern Atlantic coastlines of North America and Europe

Halichoerus grypus macrorynchus (Hornschuch & Schilling 1851) – Baltic grey seal

Distribution: Baltic Sea, from Estonia to Denmark

Behaviour

Grey seals gather in large groups during the mating/pupping and moulting seasons. Throughout the rest of the year, they roam alone, in small groups, or in large aggregations, either on land or at sea. On average, they can consume four to six percent of their body weight in food each day, but do not feed during the mating/pupping or moulting seasons. Their excellent vision and hearing make them effective hunters. They often hunt in groups, which facilitates their ability to catch prey. They primarily feed on fish (mostly sand eels, hake, whiting, cod, haddock, pollock, and flatfish), crustaceans, squid, octopuses, and occasionally even seabirds. Their diet varies depending on age, sex, season, and geographic region.

Diving and swimming

Grey seals exhibit various movement patterns in their behavior. They travel between haul-outs, which are places where they rest on land, go on short trips, and also rest near the haul-out sites. When they travel, they move horizontally in a direct and relatively fast manner, with V-shaped dive profiles. During short trips, they swim slower and follow square-wave dive profiles, where they spend about 60% of the total dive duration at the maximum depth. Resting behavior involves shallow dives near the haul-out sites and no specific lateral movement. Their impressive navigational abilities are evident as they demonstrate rapid and direct swimming between distant haul-out sites (Thompson et al. 1991).

Between May 2003 and May 2007, 80 grey seals were tagged with satellite-relay data logger in the UK and Canada. The maximum dive depth recorded was 477 m. However, 95% of all recorded locations were associated with water depths of less than 127.5 m and 95% of all recorded maximum dive depths were less than 113 m (Boehme et al. 2012).

Western North Atlantic grey seals preferred water temperatures range from 0°C to 20°C while the range from the eastern North Atlantic grey seals spans from 8.5°C to 18.5°C (Boehme et al. 2012).

Hauling out and social

Haulout pattern of grey seals in the Baltic Sea during summer and early winter were observed from from 1989 to 1996 (Sjöberg et al., 1999). The time of day had the most significant influence on the seals’ haulout patterns, with the highest number of seals on land during the night. Season and specific habitat characteristics also played a role in the haulout pattern. The researchers suggest that the nocturnal haulout pattern is influenced by changes in prey behavior and distribution.

Breeding

The time of birth can vary from late September to early March, depending on the population in question. The breeding habitat, i.e. those places where the grey seal gives birth to her pups, can also vary. Grey seals breed in caves (the Faroe Islands, Scotland and Wales), on rocky islets (Iceland, Norway and some of the British Isles) and ice (in the Baltic and near Canada). Some grey seals therefore breed relatively dispersed, while others give birth in very dense colonies.

A study by Boness & James (1971) of a land-breeding colony of grey seals on Sable Island in the western Atlantic revealed interesting breeding behavior. Both males and females arrive at the breeding beach about a week before the breeding season, and shortly after the first pup is born, they don’t stay on the beach for long. Female seals, being social animals, tend to return to the same part of the beach annually for giving birth. During their approximately two and a half week stay, they form temporary groups that change daily while staying close to their birth site. As the cows’ receptive period approaches, they become thinner and less active, without overtly displaying signs of receptivity.

In contrast, male grey seals do not establish territories or dominance hierarchies. Instead, they compete for tenure, seeking the right to remain near the shifting population of females. Tenured bulls periodically test nearby cows’ receptivity and position themselves strategically to be close to females in estrus or those about to enter this state (Boness & James, 1971).

Acoustics

Aquatic and terrestrial animals use different mechanisms in sound generation. However, grey seals efficiently use their vocal tracts in both environments. Nowak et al. (2020) recorded and analysed the variety of sounds emitted by grey seals both underwater and above the water surface using microphones and hydrophones. You can hear listen to the underwater audio recordings, surface recordings and watch video footage.

The vocalisations were classified into three groups based on acoustic differences, and their temporal and spectral parameters were studied to understand the underlying sound generation mechanisms. The first group was characterised as tonal vocalisations with multiple harmonic components. The sounds were produced by completely and partially submerged seals, and also on the surface. Adult males and females emitted vocalisations underwater while sounds produced on surface were primarily communication between mothers and pups. The second group of vocalisations were a series of short bursts without any distinct tonal components which males produced only underwater. The third group was a series of short, pulsed sounds with several distinct harmonic components which were only heard underwater (Nowak 2020).

Reproduction

Breeding occurs on islands, isolated beaches, or on pack ice. There are regional variations in timing of grey seal breeding (see Nilssen & Haug 2007) and the breeding occurs either in the autumn or in the spring. The gestation period is 11.5 months, including a 3-month delay in the implantation of the fertilised egg. Grey seals give then birth to a single pup. Pups are born with a silky white fur that is moulted by the end of the lactation period, which lasts around 15–20 days. Pupping sites are usually on isolated skerries or uninhabited islands. In Canada, and in the Baltic, spring-breeding seals may give birth on sea ice as well (NAMMCO 2016b).

Molting grey seal pup © Sandra Granquist

Foraging

Grey seals are generalist predators, consuming a wide variety of species. Moreover, their diet varies seasonally and geographically, but the species is considered to be largely demersal or benthic feeders (Bowen et al. 1993).

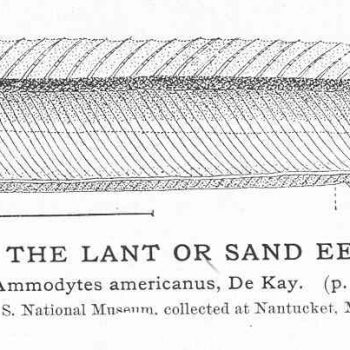

The grey seal is a large consumer of sandeel (Ammodites spp.), which at times can be over 50% of their diet (Bowen & Harrison 1994, Hammond et al. 1994, Beck et al. 2007). In a study conducted in Canada, sandeels and redfish (Sebastes sp.) together accounted for 40-91% of the diet (Bowen & Harrison 1994). Atlantic Cod can also be an important part of the diet in some areas and seasons (Hammill et al. 2014). There is ongoing debate about the possible negative impacts of seal predation on certain groundfish populations. One factor contributing to this debate is the growth in grey seal populations in eastern Canadian waters over the past five decades and the concurrent decline, or in some cases collapse, of several groundfish populations in the 1990s (Hammill et al. 2014).

Iceland

The main prey species are cod (Gadus morhua), sand eels (Ammoditdae), catfish (Anarhichas lupus), saithe (Pollachius virens) and lumpsucker (Cyclopterus lumpus) (Hauksson & Bogason 1997).

Faroe Islands

In the Faroe Islands, grey seals mainly prey on haddock (Melanogrammus aeglefinus), catfish (Anarhichas lupus), sandeel (Ammodytes sp.), lemon sole (Microstomus kitt), cod (Gadus morhua) and saithe (Pollachius virens) (Mikkelsen et al. 2002).

Norway

The Norwegian Institute of Marine Research and UiT the Arctic University of Norway conducted research on the feeding habits and prey consumption of grey seals (Nilssen et al. 2019). Between 1999 and 2010, they examined 182 grey seal gastrointestinal tracts and 199 fecal samples collected in Finnmark, Nordland, and Rogaland counties. The study revealed that the most important prey for grey seals were saithe (Pollachius virens), cod (Gadus morhua), and wolffish (Anarchichus spp). Seals aged five years or older mainly consumed Wolffish. The data did not indicate significant temporal or spatial variations in the main prey items in the grey seal diet. However, during spring in Finnmark, seals consumed capelin (Mallotus villosus), suggesting that seasonally abundant pelagic fish species could be regionally important.

Nilssen et al. (2019) estimated total annual grey seal consumption of various species using bio-energetic modelling. The input variables were seal numbers, energy demands, diet composition in terms of biomass, and energy densities of prey species. Assuming the observed grey seal diet composition in the sampling areas was representative for the diet along the Norwegian coast, the mean total annual consumption by 3850 grey seals was estimated to be 8084 tons in Norwegian waters; saithe (3059 tons), cod (2598 tons) and wolffish (1364 tons).

Habitat use

Satellite tags were deployed on five grey seals in Iceland to map habitat use of recently weaned pups during their first year of life (Baylis et. al., 2019). In general, pups either remained close to the tagging location or dispersed up to 300 km to the east of Iceland. Maximum foraging trips distances spanned from 20 to 160 km while their maximum duration ranged from 4.3 to 20.8 days. They were typically restricted to the continental shelf, which presumably reflects a preference for benthic foraging, as is reported for grey seals at other breeding locations (Baylis et al., 2019).

Distribution and Habitat

Grey seals inhabit the temperate waters of the North Atlantic. They usually move in specific corridor areas to travel between their foraging areas offshore and their haul-out sites on land (Jones et al. 2015). Satellite telemetry data from Canada show that West Atlantic grey seals perform much longer foraging trips (averaging 5–12 days) and often travel much larger distances than East Atlantic grey seals (Breed et al. 2009).

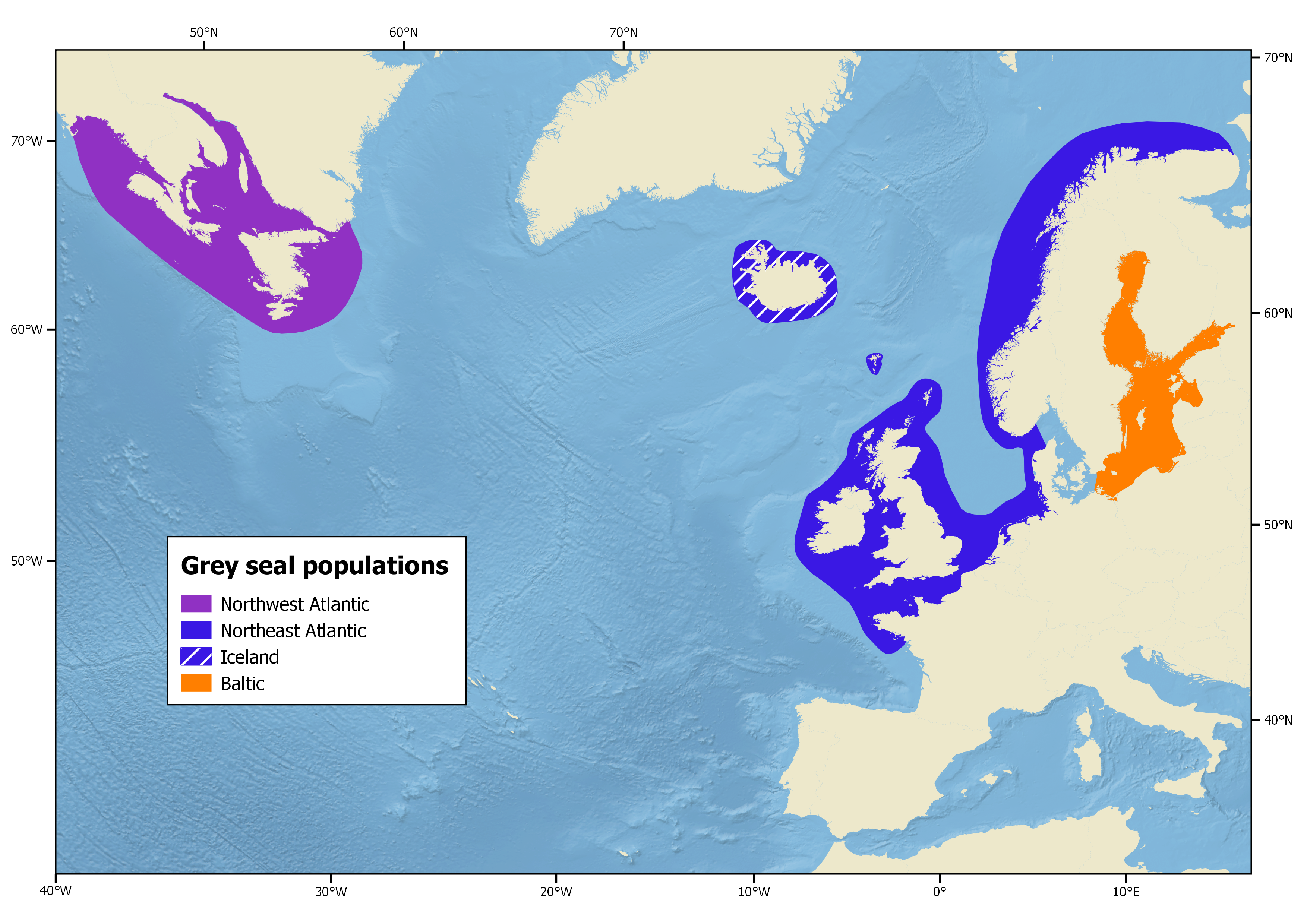

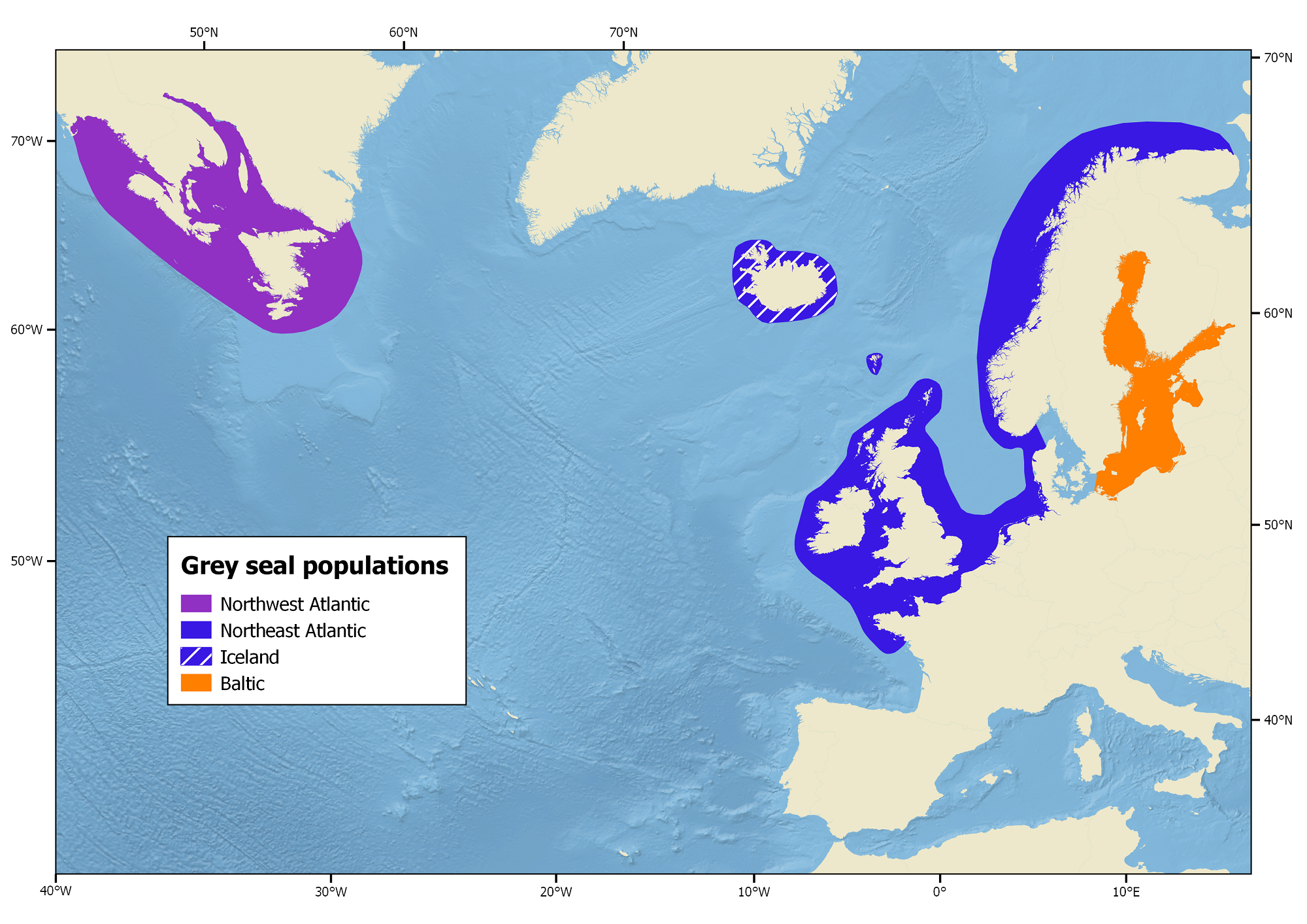

North Atlantic Stocks

Grey seals only inhabit the North Atlantic and 3 populations exist: the Northeast Atlantic, the Northwest Atlantic and Baltic Sea populations.

Northeast Atlantic

The Northeast Atlantic population centres around the British Isles, ranging from Iceland, eastward along the coast of France, and north to Norway and the Kola Peninsula, Russia (Haug et al. 1994).

A recent preliminary study using more than 1900 RADseq loci genotyped in 192 grey seals supports the existence of a finer scale genetic structure within the NE Atlantic, corresponding to separate populations in Iceland, Wales (and possibly Ireland), the North See region, Norway and Russia (NAMMCO 2023b, p. 20). Thus, future stock assessments should consider NE Atlantic grey seals as comprising several distinct populations. RADseq genotyping utilises small pieces of DNA that are fragmented into even smaller fragments, and are subsequently analysed to observe how they vary from one organism to another.

The grey seal colony in the Faroe Islands evolved from UK colonies sometimes after the postglacial period, and due to geographical isolation, the population is now genetically significantly different from Norwegian grey seals (Klimova et al. 2014). Tracked grey seals in the Faroe Islands have showed only restricted local movements along the coastal waters inside the 150-meter depth contour of the archipelago. Movements of UK grey seals to the Faroe Islands have been documented by both conventional and telemetry tagging (Mcconnell et al. 1999, Matthiopoulos et al. 2004, Mikkelsen 2007), but the intensity seems low, excluding any tight connections between the areas.

Norwegian populations are, on the other hand, connected to the UK and Russian populations (Henriksen et al. 2007).

Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea population inhabits the central Baltic area, bounded by Sweden, Finland and Estonia (Harding et al. 2007).

The Baltic grey seal (Halichoerus grypus macrorynchus) is a recognised subspecies of the Atlantic grey seal (H.g.grypus). This subspecies delineation has been determined by geographical separation and differences in the timing of births (October–January in the Northeast Atlantic, and January–March in the Baltic population) (NAMMCO 2016a).

Northwest Atlantic

The Northwest Atlantic population occurs from the North-eastern United States to Cape Chidley at the northern tip of Labrador (60° N), with the largest concentration around Sable Island, off the Nova Scotia coast. Canadian grey seals form a single genetic population that is divided into three groups for management purposes based on the location of breeding sites. These sites are the Sable Island, the Gulf of St Lawrence and the coast of Nova Scotia with differing proportions of born pups per site over the years (NAMMCO 2016a).

Northeast Atlantic

NAMMCO countries

In Iceland, the most recent aerial census conducted in 2017 was used to estimate the grey seal population, which was found to be 6269 (95% CI: 5375–7181). Among the areas surveyed, Breiðafjörður stood out as the most significant pupping location in Iceland, accounting for 58% of the total pup production in 2017 (Granquist & Hauksson 2019). A new count was carried out in 2022, and the analysis is expected to be finalised in late 2023 (NAMMCO 2023a).

In the Faroe Islands, the population was counted to number a minimum of 661 animals based on the highest counts for each island and survey year 2018, 2019, and 2021 (NAMMCO 2023a).

In Norway, new boat-based surveys carried out in 2017–2021 showed a significant decrease in the grey seal pup production compared with the counts in the period 2007–2008, particularly in mid Norway and most likely due to high levels of by-catch in the monkfish fishery (Nilssen and Bjørge, 2017). A total population of 3,850 (95% CI: 3504-4196) grey seals was estimated in 2018, compared to 8740 (95% CI: 7320-10170) animals in 2011 (Nilssen et al. 2019).

Outside NAMMCO

For British grey seal populations, Bayesian state-space modelling methodology has been used. The estimated adult population size in in 2020 was 157,300 (approximate 95% CI 144,600-169 400; SCOS, 2021).

Following a remarkable increase from 4,521 in 2014, the total number of grey seals in the Wadden Sea (Danish, German and Dutch coasts) was 9,000 during the moulting period in 2021 (Brasseur et al., 2021).

In France, the most recent data available was a count of 3330 grey seals in 2022 (unpublished data) Abundance has been increasing the last years, with 2602 grey seals reported for 2021 and 1350 in 2020 (ICES 2022).

No updated population estimate from Russia has been available since the early 1990s, when the total grey seal population was calculated to be about 3,400 animals (Haug et al. 1994).

Northwest Atlantic

Grey seals form a single population that Canada divided into two herds in for management purposes based on the location of breeding sites: Scotian Shelf (Sable Island and Coastal Nova Scotia) and Gulf of St. Lawrence (Gulf). The most recent assessment of Canadian grey seals was completed in 2021. The estimated total abundance for grey seals in 2021 was 366,400 (95% CI= 317,800– 409,400, rounded to the nearest 100). The model estimated a total grey seal pup production in Atlantic Canada of 98,200 (95% Confidence Interval (CI)= 86,800–109,700), with 81,300 (95% CI= 74,500–88,100) born on the Scotian Shelf, and 16,900 (95% CI= 12,300–21,500) born in the Gulf. The rate of growth of the population has continued to slow. Total abundance increased at a rate of 1.5% per year between 2016 and 2021 (DFO, 2022c).

In the United States, number of pups born at US breeding colonies are used to approximate the total size (pups and adults) of the grey seal population in US waters, based on the ratio of total population size to pups in Canadian waters (4.3:1). Using this approach, the abundance estimate in US waters for the 2021 pupping season is 27,911 with a minimum population of 27,454 (Wood et al., 2022).

Baltic Sea

The last population survey in 2021 indicated 42,000 seals, indicating that the population is still growing (ICES, 2022). The maximum number (not corrected for individuals in the water) counted during 2–3 replicate surveys in each sea area in the Baltic is used for assessing abundance.

Summary of abundance and trends of grey seals in the North Atlantic.

Stock Status

Greenland

The current status of grey seals in Greenland remains unknown, but it is assumed that they are few in number, with the total adult population likely being less than 250 individuals. In the Greenland Red List, this places them in the category of “critically endangered.” Up until now, 2-3 different individuals have certainly bvisited, but there might be many more. The first documented grey seal encounter was in 2009.

Iceland

Since 1982, regular aerial surveys during the pupping period have allowed population estimates of Icelandic grey seals. In the 2017 census, the pup production was calculated to be 1452 (95% CI=1385‐1529), leading to an estimated population of 6269 (95% CI=5375‐7181) animals (Granquist & Hauksson 2019). Key pupping areas are Breiðafjörður in West Iceland, with other important breeding sites on the northwest coast (Strandir and Skagafjörður) and the south coast (Öræfi and Surtsey).

Presently, the population is approximately 32% smaller than in the 1982 census. In 2017, the grey seal population surpassed the governmental management objective of 4100 animals. However, according to the Icelandic national red list, following IUCN criteria, the current population level categorizes grey seals as “Vulnerable.”

Faroe Islands

Limited biological knowledge about grey seals in the Faroe Islands stems from their inaccessible nature and lack of studies. Irregular observations around the islands indicate that the Faroese population has not seen a rapid increase, as has been evident for colonies around Britain and in West Atlantic (Bowen et al. 2003). Historical hunting and protective removals around salmon sea farms since the 1980s likely prevented the population from reaching high numbers. However, in 2020, a law banned the grey seal cull, ending direct hunting of the animals (Mikkelsen & Hoydal, 2021). Storms may also cause high pup mortality by exposing suitable breeding grounds (Mikkelsen 2007). The first population assessment took place in 2018, 2019, and 2021, with the highest count of 661 animals representing the best representative abundance number on each of the 18 survey islands, regardless of the survey year (NAMMCO 2023a).

Norway

1960-1999

Early investigations on grey seals during the 1960s, based on interviews with fishers, lighthouse crews, and seal hunters suggested that no animals were born south of Stad, while an estimated 660 pups were born annually in the areas north of Stad (62°N). Since then, several visual surveys carried out over the years have indicated that the population has increased and that the range has expanded (see Øigård et al. 2012).

Data from aerial and boat surveys carried out between Rogaland and Finnmark during 1974–1988 resulted in a minimum estimate of around 3100 grey seals. From 1987 to 1992, visual surveys covering the same areas along the coast indicated that the population had increased to around 4000–5000 animals. During the period 1996–1999, aerial photo surveys to estimate grey seal pup production were flown in the area from Froan (64°N) to Lofoten (67°N), and the number of moulting grey seals were registered in Troms and Finnmark counties (69–71°N). These investigations resulted in a total population estimate of around 4400 grey seals along the Norwegian coast from Froan and northwards.

2001-2011

In 2001–2003, boat-based surveys along the entire coast from eastern Finnmark to southern parts of Rogaland provided estimates of annual pup production of nearly 1200. Combined boat and aerial photo surveys in the same areas during September–December 2006–2008 yielded a minimum pup production estimate of 1275. In 2011, Øigård et al. (2012) developed a Bayesian age-structured population dynamics model for the Norwegian grey seal population, utilizing priors for various parameters. Model runs indicated an increase in the abundance of the total Norwegian grey seal population during the last 30 years, suggesting a total of 8740 (95% confidence interval: 7320–10 170) animals in 2011.

2014-2021

However, new boat-based surveys carried out between 2014 and 2021 did show a significant decrease in the grey seal pup production compared with the counts in 2007–2008, particularly in mid Norway and most likely due to high levels of by-catch in the monkfish fishery. The most recent pup production estimate is 770 pups which corresponds to a total stock of 3850 (95% confidence interval: 3504 – 4196) animals (Nilssen et al. 2019).

Greenland

The first documented grey seal encounter was in 2009 and Greenland granted the grey seal protection status in November 2010.

Iceland

In 2006, the Icelandic government proposed a management objective, recommending a target grey seal population size of 4,100 (NAMMCO 2006). Management actions should be initiated if the population dropped appreciably below that number, although no specific population regulating method is mentioned. In 2019, Iceland introduced a general ban on seal hunting with an exception under special licences for subsistence use.

Faroe Islands

In the late 1960s seal hunting virtually ceased with new weapon regulations that banned the use of the rifle as a hunting weapon. With the introduction of fish farms in the early 1980s, farmers with a licence were given permission to possess rifles to minimise problems of seals’ interaction with fish farms. From 2010, shot animals were supposed to be reported to the governmental authorities. The total number of grey seals reported removed at aquaculture farms ranged from 150 to 250 annually, which represented approximately 10-20% of the estimated population size (NAMMCO 2016a). This practice of killing grey seals interacting with fish farming installations is, however, banned by law since 14 May 2020 (Mikkelsen & Hoydal, 2021).

Norway

The Ministry of Fisheries and Coastal Affairs adopted and implemented management plans for coastal seals in Norway on 5th November 2010. The goal of the management plans is to ensure viable populations of harbour and grey seals within their natural distribution areas. Grey seals are monitored by counting pups and the government decided that the population should be stabilised to ensure that at least 1,200 pups are recorded annually. Quotas for removals are based on scientific advice in accordance with the management plan. Three geographical Management Units (MU) for grey seals are used, based on biological evidence (the Southern MU from Lista to Stad; the Central MU from Stad to Lofoten; and the Northern MU from Vesterålen to Varanger). The county authorities manage the administration of hunting licenses and hunting statistics (NAMMCO 2016a).

Baltic

The continuous distribution of the species and the free movement of individuals in the Baltic Sea result in treating the species as a single management unit. Moreover, the HELCOM 2006 Seal Recommendation defines the grey seal management principles. The long-term objectives are: to allow population growth towards carrying capacity, to allow breeding seals to expand to suitable distribution in all areas of the sea, and attaining a health status that secures the continued existence of the populations. The ecological carrying capacity defines the population target limit (HELCOM 2006).

United Kingdom

Under the Conservation of Seals Act 1970, the UK Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) has a duty to provide scientific advice to the government on matters related to the management of seal populations. NERC has appointed a Special Committee on Seals (SCOS) to formulate this advice. SCOS fives formal advice annually based on the latest scientific information provided by the Sea Mammal Research Unit (SCOS 2021).

Canada

The governmental organization Fisheries and Ocean Canada manages the Canadian grey seal population. Currently, the Canadian grey seal is considered a data-rich species, with three or more abundance estimates over a 15-year period, and the most recent estimate obtained within the last five years. To determine sustainable levels of exploitation, information on fecundity and/or mortality within the past five years is also required.

All Canadian Atlantic seal populations are managed under a precautionary approach, which identifies three types of reference points:

-

The Critical Limit: This level indicates that a population has likely experienced serious and irreversible harm, and all human-induced removal should cease below this point.

-

The Precautionary Reference Point: This level signifies that the population is considered healthy, and conservation is not of the greatest concern.

-

The Target Reference Point: This level is the desired population size that management aims to achieve.

Northeast Atlantic

Although, traditionally, grey seal hunt played an important role in Iceland, seal hunt in general has ceased the last few decades and in 2019 Iceland introduced a general ban on seal hunting. It is possible to apply for exception under special licences for subsistence use, however, this hunt has only been in low numbers. Grey seal hunting in Iceland primarily focuses on the seal pup hunt during the autumn season. The main reasons for hunting pups are to obtain their skin, meat, blubber, and flippers. The meat is used fresh, salted, or smoked. The traditional hunt involved taking pups in the pupping areas when they are a few weeks old, just towards the end of lactation, using a seal club or a rifle from a very short distance. Hunters of adult grey seals only use a rifle.

Traditional seal hunting has virtually ceased in the Faroe Islands after the late 1960s. There is no longer any tradition to utilise seal meat, blubber or skin in the Faroe Islands (NAMMCO 2016b).

Norwegian grey seals are subject to a non-commercial game hunt. Hunters usually shoot the animal from land and retrieve it in the water with the support of a small boat.

Baltic

The Baltic grey seal population is now recovering after commercial over-hunting in the first half of the 20th century. Sweden stopped seal hunting entirely in 1975, and Finland followed suit in 1982, but both countries later resumed hunting in 2001 and 1997, respectively. At the present time, both countries strictly regulate the hunt and prohibit hunting from boats. During the spring period, seals are hunted on the ice. Seals sink quickly in the Baltic because the salinity of the water is very low and since the water is not very clear, retrieval of sunken seals is difficult. Therefore, hunters favor areas of shallow water where they can retrieve sunken seals more easily. Hunting is prohibited in seal reserves, encompassing all major resting-places for seals in the Baltic (NAMMCO 2016b).

Northwest Atlantic

A commercial juvenile grey seal hunt usually runs from early February until early March, mainly along the eastern shore of Nova Scotia and in the southern Gulf of St Lawrence. Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) has not assigned a Total Allowable Catch (quota) for the Atlantic seal hunt since 2016, as participation in the seal hunt, and the market demand for seals, is low (DFO 2022a). However, the DFO actively monitors the landings, and they have the authority to close the hunting within short notice (DFO 2022b).

Catches in NAMMCO member countries since 1992

| Country | Species (common name) | Species (scientific name) | Year or Season | Area or Stock | Catch Total | Quota (if applicable) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Faroe Islands | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2023 | Faroes | 0 | |

| Faroe Islands | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2022 | Faroes | 0 | |

| Faroe Islands | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2021 | Faroes | 0 | |

| Faroe Islands | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2020 | Faroes | N/A | |

| Faroe Islands | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2019 | Faroes | 34 | |

| Faroe Islands | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2018 | Faroes | 50 | |

| Faroe Islands | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2017 | Faroes | 117 | |

| Faroe Islands | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2016 | Faroes | 111 | |

| Faroe Islands | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2015 | Faroes | 140 | |

| Faroe Islands | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2014 | Faroes | 102 | |

| Faroe Islands | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 1992-2013 | Faroes | N/A | |

| Iceland | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2023 | Iceland | 1 | 13 |

| Iceland | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2022 | Iceland | 0 | 33 |

| Iceland | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2021 | Iceland | 0 | 21 |

| Iceland | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2020 | Iceland | 4 | 58 |

| Iceland | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2019 | Iceland | 24 | |

| Iceland | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2018 | Iceland | 24 | |

| Iceland | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2017 | Iceland | 39 | |

| Iceland | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2016 | Iceland | 61 | |

| Iceland | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2015 | Iceland | 30 | |

| Iceland | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2014 | Iceland | 2 | |

| Iceland | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2013 | Iceland | 1 | |

| Iceland | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2012 | Iceland | 106 | |

| Iceland | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2011 | Iceland | 107 | |

| Iceland | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2010 | Iceland | 98 | |

| Iceland | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2009 | Iceland | 71 | |

| Iceland | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2008 | Iceland | 180 | |

| Iceland | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2007 | Iceland | 269 | |

| Iceland | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2006 | Iceland | 211 | |

| Iceland | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2005 | Iceland | 213 | |

| Iceland | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2004 | Iceland | 298 | |

| Iceland | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2003 | Iceland | 505 | |

| Iceland | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2002 | Iceland | 341 | |

| Iceland | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2001 | Iceland | 430 | |

| Iceland | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2000 | Iceland | 503 | |

| Iceland | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 1999 | Iceland | 662 | |

| Iceland | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 1998 | Iceland | 567 | |

| Iceland | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 1997 | Iceland | 1276 | |

| Iceland | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 1996 | Iceland | 964 | |

| Iceland | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 1995 | Iceland | 1327 | |

| Iceland | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 1994 | Iceland | 1615 | |

| Iceland | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 1993 | Iceland | 1760 | |

| Iceland | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 1992 | Iceland | 1976 | |

| Norway | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2023 | Finmark | 47 | 115 |

| Norway | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2023 | Troms | 10 | 25 |

| Norway | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2023 | Stad - Lista | 39 | 60 |

| Norway | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2023 | Total | 96 | 200 |

| Norway | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2022 | Finnmark | 46 | 115 |

| Norway | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2022 | Troms | 11 | 25 |

| Norway | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2022 | Stad - Lista | 76 | 60 |

| Norway | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2022 | Total | 133 | 200 |

| Norway | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2021 | Finnmark | 6 | 115 |

| Norway | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2021 | Troms | 6 | 25 |

| Norway | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2021 | Stad - Lista | 17 | 60 |

| Norway | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2021 | Total | 29 | 200 |

| Norway | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2020 | Finnmark - Lofoten | 4 | 140 |

| Norway | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2020 | Lofoten - Stad | 0 | 0 |

| Norway | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2020 | Stad - Rogaland | 12 | 60 |

| Norway | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2020 | Total | 16 | 200 |

| Norway | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2019 | Finnmark - Lofoten | 22 | 140 |

| Norway | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2019 | Lofoten - Stad | 0 | 0 |

| Norway | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2019 | Stad - Rogaland | 40 | 60 |

| Norway | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2019 | Total | 62 | 200 |

| Norway | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2018 | Norway coast | 66 | 200 |

| Norway | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2017 | Norway coast | 81 | 200 |

| Norway | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2016 | Norway coast | 33 | 210 |

| Norway | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2015 | Norway coast | 82 | |

| Norway | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2014 | Norway coast | 216 | |

| Norway | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2013 | Norway coast | 194 | |

| Norway | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2012 | Norway coast | 64 | |

| Norway | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2011 | Norway coast | 111 | |

| Norway | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2010 | Norway coast | 363 | |

| Norway | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2009 | Norway coast | 516 | |

| Norway | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2008 | Norway coast | 458 | |

| Norway | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2007 | Norway coast | 456 | |

| Norway | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2006 | Norway coast | 272 | |

| Norway | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2005 | Norway coast | 379 | |

| Norway | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2004 | Norway coast | 302 | |

| Norway | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2003 | Norway coast | 353 | |

| Norway | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2002 | Norway coast | 110 | |

| Norway | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2001 | Norway coast | 105 | |

| Norway | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 2000 | Norway coast | 176 | |

| Norway | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 1999 | Norway coast | 130 | |

| Norway | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 1998 | Norway coast | 34 | |

| Norway | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 1997 | Norway coast | 36 | |

| Norway | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 1996 | Norway coast | 31 | |

| Norway | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 1995 | Norway coast | 31 | |

| Norway | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 1994 | Norway coast | 31 | |

| Norway | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 1993 | Norway coast | 31 | |

| Norway | Grey seal | Halichoerus grypus | 1992 | Norway coast | N/A | |

This database of reported catches is searchable, meaning you can filter the information, e.g. by country, species or area. It is also possible to sort it by the different columns, in ascending or descending order, by clicking the column you want to sort by and the associated arrows for the order. By default, 10 entries are shown, but this can be changed in the drop-down menu, where you can decide to show up to 100 entries per page.

Carry-over from previous years are included in the quota numbers, where applicable.

You can find the full catch database with all species here.

For any questions regarding the catch database, please contact the Secretariat at nammco-sec@nammco.no.

Other human impacts

The most important anthropogenic sources of mortality for grey seals (other than hunting) are by-catch during fishing operations, removal during interactions with fish farms, and pollution.

By-catch

Although we know that commercial fisheries, especially gillnet fisheries, cause a certain level of grey seal mortality as by-catch, accurately estimating this level is challenging due to the possibility of misidentifying seal species in logbook and inspector reports. This is particularly the case for young seals, where grey and harp seals can be misidentified and reported as harbour seals. There are now attempts underway in some countries to minimise this misidentification through the use of photos and analysis of DNA samples.

Iceland

In Iceland, the main fisheries of concern for grey seal by-catch is the lumpsucker fishery. In a report from 2019, just below 1000 grey seals were reported to be caught annually in lumpsucker gillnets between 2014–2018 (Marine and Freshwater Research Institute 2019). The most reliable by-catch data for cod gillnets comes from the March-April research survey and from the reports of fisheries observers (1% coverage of the fleet and representative geographical spreading). Cod gillnet fisheries also causes grey seal by-catch but to a much lower extent than the lumpsucker fishery. Estimating by-catch in cod gillnets remains difficult due to a lack of data outside of April.

Faroe Islands

In the Faroe Islands, where a shallow-water gillnet fishery is not practiced, long-line and trawl fishery may impose an insignificant a source of mortality for grey seals (NAMMCO 2016a).

Norway

In Norway, the levels of by-catch in fishing operations have been estimated using a range of data sources over the years, including: mark recapture data, data from the Coastal Reference Fleet (CRF) (a monitored segment of the coastal fishing fleet), and modelling of population trajectories. Using data from the CRF (scaled up to the whole fleet using national landing statistics) is currently the preferred data source for by-catch estimates. Between 2006-2020, a total by-catch of 363 grey seals (95% CI 298 – 474) was estimated in the Norwegian commercial gillnet fisheries (Moan & Bjørge 2021). Grey seal by-catch in Norway seems comparable to the annual hunt and thus should be taken into account in population assessments. It is also likely that the level of by-catch has been increasing in recent years north of 62°N due to an increase in fishing effort with large mesh gill nets, particularly in the monkfish fishery.

Baltic

There is an increasing problem with interactions between seals and commercial fisheries in the Baltic, and herring gillnet fishery is particularly vulnerable to this (NAMMCO 2016b).

Canada

In Canadian waters in the Northwest Atlantic, no data are available on incidental catches in fishing operations, although the numbers are thought to be small (NAMMCO 2016a).

Fish farming

Until recently, the most significant human-grey seal interaction in the Faroe Islands involved the culling of seals in connection with salmon farming.. This practice is, however, now banned by law (Mikkelsen & Hoydal, 2021).

Before the ban, the total numbers of grey seals removed at aquaculture farms in the Faroe Islands were estimated to be around 150-250 grey seals annually. These removal levels were around 10-20% of the approximate estimate of the population size (NAMMCO 2016a).

Pollutants

Pollutants have been problematic over a period of several decades, especially for the Baltic grey seal population. In a long term study, Bergman (1999) reported reduced a reproductive ability, reduced pregnancy rate, and lesions on the female reproductive organs, as well as a disease complex in adult individuals of both sexes. This, together with hunting, was seen to be the major contributor to the population decrease in the 1970s.

Persistent Organic Pollutants

Grey seals’ tissues, particularly their blubber, contain large concentrations of Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) (Sørmo et al., 2003). When food intake is irregular or nonexistent during breeding, lactation and moulting, important amounts of POPs are mobilised from blubber into the bloodstream, exposing targeted organs to increased concentrations of toxicants (Vanden Berghe et al., 2010). During lactation, seals produce lipid-rich milk containing high levels of POPs (Sørmo et al., 2003). Suckling newborns are thus exposed to high amounts of toxic chemicals, while being in a critical developmental period of their life. Pup or juvenile grey seals exposed to POPs, even to low concentrations, had reduced immune competence and impairment of the thyroid hormone (Hall et al., 2003, Sørmo et al., 2009).

A study by Robinson et al. (2019) compared POP concentrations in the blubber of weaned grey seal pups from the Isle of May, Scotland, between 2002 and 2015–17. By 2017, total dioxin-like polychlorinated biphenyls (ΣDL-CBs) and total non-dioxin-like polychlorinated biphenyls (ΣNDL-CBs) had decreased to about 75% of 2002 levels. However, organochlorine pesticides (OCPs) such as dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (ΣDDT), dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene (DDE), and dichlorodiphenyldichloroethane (DDD), along with some CB congeners, did not decrease over the 15-year period, likely due to the difficulty of detecting small changes at low concentrations. High DDE levels and no change in DDD suggest that this is due to low excretion of DDT metabolites rather than recent exposure. The limited decline in many POPs over 15 years indicates that risks persist for energy balance, endocrine status, and immune function in grey seal pups, which has implications for conservation and management efforts for this species.

Greenland

There is no current research on grey seals in Greenland.

FAROE ISLANDS

A programme for estimating the abundance of grey seals in the Faroe Islands started in summer 2018. Researchers surveyed all islands in the archipelago, except the east side of Suðuroy, by boat in 2018, 2019, and 2021 (Mikkelsen and Hoydal (2022). They visited each island 1–3 times and counted all seals hauled-out and in the water. Additionally, in high-density areas, footage captured by drone was used to improve accuracy of the counts (Mikkelsen & Hoydal, 2022).

Moreover, researchers tagged grey seals in Vestmannasund, with two seals tagged in 2020 and three in 2022, to study the potential disturbance caused by recently installed ocean turbines in the narrow strait. They also conducted land-based observations of marine mammal occurrences in the area between June and August from 2020 to 2022. As a result, the study found that both seals tagged in 2020 predominantly stayed within the strait for a significant portion of the time. Although they undertook several longer-distance trips, they never ventured into offshore areas (Mikkelsen & Hoydal, 2021).

The three seals tagged in 2022 did, although not providing good data, show the same affiliation to the study area.

The plan is to expand the summer census to include camera traps and satellite tracking, in order to study grey seal behaviour and to further improve the accuracy of the abundance estimate (Mikkelsen & Hoydal, 2022).

ICELAND

The latest aerial census to estimate the current status of the Icelandic grey seal population was conducted in 2022 and the analysis is ongoing as of 2023. Efforts to estimate by-catch of grey seals in fisheries are also ongoing at the MFRI.

In 2016, the Marine and Freshwater Institute (MFRI), the Icelandic Seal Center (ISC), the Natural History Museum of Denmark, and Main University initiated a study of Icelandic grey seal genetics. The analysis is ongoing (Granquist et al., 2023).

Projects

The MFRI initiated a project investigating environmental toxicants in seals in Icelandic waters in 2017 (Granquist et al., 2020). The focus of the project is to investigate the contents of new contaminants of concern in marine mammals, including new brominated flame retardants and PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances). The project is an international cooperation between Sweden (Naturhistoriska Riksmuséet and Stockholm University), Greenland (Grönlands Naturinstitut) and MFRI (Iceland). Spaan et al. (2020) published a paper on fluorine mass balance and suspect screening in marine mammals from the Northern Hemisphere.

In cooperation with the Icelandic Institute of Natural History, a study was conducted to examine the effects of seals and seabirds on plant succession on the island of Surtsey. The results of this study were published in 2020, and continuous monitoring is still ongoing (Magnússon et al., 2020, Víkingsson et al., 2021).

The study found that grey seals and sea birds play significant roles as drivers of plant succession on the northern spit of the island. Grey seals haul out and breed in the fall, while only a few pairs of seagulls breed in the spring in that area. Regarding Nitrogen (N) input, the study estimated that in 2019, grey seals contributed approximately 9-13 kg N/ha from the sea to the land. In comparison, the seagulls breeding in the same area were estimated to input around 5-30 kg N/ha/yr during the period from 2015 to 2019.

NORWAY

The Institute of Marine Research performs regular grey seal pup counts along the Norwegian coast (Haug et al. 1994, Nilssen & Haug 2007, Øigård et al. 2012). The most recent pup production survey was carried out between 2017 and 2021 (Haug & Henden, 2023).

Baylis, A.M., Þorbjörnsson, J.G., dos Santos, E. and Granquist, S.M. (2019). At-sea spatial usage of recently weaned grey seal pups in Iceland. Polar Biology, 42(11), 2165–2170. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00300-019-02574-5

Beck, C.A., Iversonn S.J., Bowen, W.D. and Blanchard, W. (2007). Sex differences in grey seal diet reflect seasonal variation in foraging behaviour and reproductive expenditure: evidence from quantitative fatty acid signature analysis. Journal of Animal Ecology, 76(3), 490–502. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2656.2007.01215.x

Bergman, A. (1999). Health condition of the Baltic grey seal (Halichoerus grypus) during two decades. APMIS, 107(1-6), 270–282. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1699-0463.1999.tb01554.x

Berta A., & Churchill, M. (2012). Pinniped taxonomy: review of cur-rently recognized species and subspecies, and evidence used for their description. Mammal Review, 42, 207–234. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2907.2011.00193.x

Boehme, L., Thompson, D., Fedak, M., Bowen, D., Hammill, M.O., et al. (2012). How Many Seals Were There? The Global Shelf Loss during the Last Glacial Maximum and Its Effect on the Size and Distribution of Grey Seal Populations. PLoS ONE 7(12): e53000. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0053000

Boness, D.J. and James, H. (1979), Reproductive behaviour of the Grey seal (Halichoerus grypus) on Sable Island, Nova Scotia. Journal of Zoology, 188: 477-500. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7998.1979.tb03430.x

Bowen, W.D. and Harrison, G.D. (1994). Offshore diet of grey seals Halichoerus grypus near Sable Island, Canada. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 112, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps112001

Bowen, W.D., Lawson, J.W. and Beck, B. (1993). Seasonal and Geographic Variation in the Species Composition and Size of Prey Consumed by Grey Seals (Halichoerus grypus) on the Scotian Shelf. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 50(8), 1768–1778. https://doi.org/10.1139/f93-198

Brasseur, S., Abel, C., Galatius, A., Jeß, A., Körber, P., Meise K., Schop J., et al. 2021. EG-Marine Mammals grey seal surveys in the Wadden Sea and Helgoland in 2020-2021. Wilhelmshaven, Germany: Common Wadden Sea Secretariat (CWSS). Retrieved from https://www.waddensea-worldheritage.org/sites/default/files/Wadden Sea_Grey_Seal_Report_2021_0.pdf

Breed, G.A., Jonsen, I.D., Myers, R.A., Bowen, W.D. and Leonards, M.L. (2009). Sex-Specific, Seasonal Foraging Tactics of Adult Grey Seals (Halichoerus grypus) Revealed by State-Space Analysis. Ecology, 90(11), 3209–3221. https://doi.org/10.1890/07-1483.1

DFO. (2022a). Seal management on Canada’s East Coast. https://www.canada.ca/en/fisheries-oceans/news/2022/05/seal-management-on-canadas-east-coast.html

DFO. (2022b). Harp and grey seal – North Shore season 2023 – CHP. https://www.qc.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/en/harp-and-grey-seal-north-shore-season-2023-chp

DFO. (2022c). Stock assessment of Northwest Atlantic grey seals (Halichoerus grypus) in Canada in 2021. DFO Can. Sci. Advis. Sec. Sci. Advis. Rep. 2022/018. https://waves-vagues.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/library-bibliotheque/41063648.pdf

Granquist, S.M. and Hauksson, E. (2019). Aerial census of the Icelandic grey seal (Halichoerus grypus) population in 2017: Pup production, population estimate, trends and current status. Marine and Freshwater Research Institution, HV 2019‐02. Reykjavík. 19 pp.

Granquist, S.M., Gunnlaugsson, Þ., Halldórsson, S.D., and Víkingsson, G.A. (2020). ICELAND -PROGRESS REPORT ON MARINE MAMMALS IN 2019. NAMMCO/28/NPR/IS-2019. https://nammco.no/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/npr_is-2018_nammco27-2019.pdf

Granquist, S.M., Halldórsson, S.D., Chosson, V., and Sigurðsson, G.M. (2023). ICELAND – PROGRESS REPORT ON MARINE MAMMALS IN 2022. NAMMCO/30/NPR/IS-2022. https://nammco.no/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/npr-is_2022.pdf

Hall, A.J., Kalantzi, O.I., Thomas, G.O. (2003) Polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) in grey seals during their first year of life — are they thyroid hormone endocrine disrupters?Environ Pollut, 126(1), 29-37. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0269-7491(03)00149-0

Hammill, M.O., Stenson, G.B., Swain, D.P. and Benoit, H.P. (2014). Feeding by grey seals on endangered stocks of Atlantic cod and white hake. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 71(6), 1332–1341. https://doi.org/10.1093/icesjms/fsu123

Harding, K.C., Härkönen, T., Helander, B. and Karlsson, O. (2007). Status of Baltic grey seals: Population assessment and extinction risk. NAMMCO Scientific Publications, 6, 33-56. https://doi.org/10.7557/3.2720

Haug, T., Henriksen, G., Kondakov, A., Mishin, V., Tormod Nilssen, K. and Røv, N. (1994). The status of grey seals Halichoerus grypus in North Norway and on the Murman Coast, Russia. Biological Conservation, 70, 59–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-3207(94)90299-2

Haug, T., and Henden, J.-A. (2023). NORWAY – PROGRESS REPORT ON MARINE MAMMALS 2022. NAMMCO/30/NPR/NO-2022. https://nammco.no/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/npr-no_2022.pdf

Hauksson, E. and Bogason, V. (1997). Comparative Feeding of Grey (Halichoerus grypus) and Common Seals (Phoca vitulina) in Coastal Waters of Iceland, with a Note on the Diet of Hooded (Cystophora cristata) and Harp Seals (Phoca groenlandica). Journal of Northwest Atlantic Fishery Science, 22, 125–135. https://doi.org/10.2960/J.v22.a11

HELCOM. (2006). Seal Expert Group First Meeting, Sigtuna, Sweden, 18-20 October 2006

Henriksen, G., Haug, T., Kondakov, A., Nilssen, K.T. and Øritsland, T. (2007) Recoveries of grey seals (Halichoerus grypus) tagged on the Murman coast in Russia. NAMMCO Scientific Publications, 6, 197-201. https://doi.org/10.7557/3.2734

ICES. 2022. Working Group on Marine Mammal Ecology (WGMME). ICES Scientific Reports. 4:61. 151 pp. http://doi.org/10.17895/ices.pub.20448942

Jones, E.L., McConnell, B.J., Smout, S., Hammond, P.S., Duck, C.D., Morris, C.D., Thompson, D., Russell, D.J.F., Vincent, C., Cronin, M., Sharples, R.J. and Matthiopoulos, J. (2015). Patterns of space use in sympatric marine colonial predators reveal scales of spatial partitioning. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 534, 235–249. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps11370

Klimova, A., Phillips, C.D., Fietz, K., Olsen, M.T., Harwood, J., Amos, W. and Hoffman, J.I. (2014). Global population structure and demographic history of the grey seal. Molecular Ecology, 23(16), 3999–4017. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.12850

Magnússon, B., Gudmundsson, G.A., Metúsalemsson, S. & Granquist, S.M. (2020). Seabirds and seals as drivers of plant succession on Surtsey. Surtsey Research, 14: 115-130. https://surtsey.is/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Surtsey-2020_14_115-130_BIOLOGY_Seabirds-and-seals-as-drivers-of-plant-succession-on-Surtsey.pdf

Marine and Freshwater Institute. (2019). Bycatch of seabirds and marine mammals in lumpsucker gillnets 2014-2018. Working paper 04 for NAMMCO By-catch Working Group. May 2020.

Matthiopoulos, J., Mcconnell, B., Duck, C. and Fedak, M. (2004) Using satellite telemetry and aerial counts to estimate space use by grey seals around the British Isles. Journal of Applied Ecology, 41(3), 476–491. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0021-8901.2004.00911.x

Mcconnell, B.J., Fedak, M.A., Lovell, P. and Hammond, P.S. (1999). Movements and foraging areas of grey seals in the North Sea. Journal of Applied Ecology, 36(4), 573–590. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2664.1999.00429.x

Mikkelsen, B. (2007). Present knowledge of grey seals (Halichoerus grypus) in Faroese waters. NAMMCO Scientific Publications, 6, 79-84. https://doi.org/10.7557/3.2724

Mikkelsen, B., Haug, T. and Nilssen, K.T. (2002). Summer Diet of Grey Seals (Halichoerus grypus) in Faroese Waters. Sarsia, 87(6), 462–471. https://doi.org/10.1080/0036482021000155745

Mikkelsen, B., & Hoydal, K. (2021). FAROE ISLANDS – PROGRESS REPORT ON MARINE MAMMALS 2020. NAMMCO/28/NPR/FO-2020-2019. https://nammco.no/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/npr-fo_2020-2019.pdf

Mikkelsen, B., & Hoydal, K. (2022). FAROE ISLANDS – PROGRESS REPORT ON MARINE MAMMALS 2021. NAMMCO/29/NPR/FO-2021. https://nammco.no/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/npr-fo-2021_final.pdf

Moan, A., Bjørge, A. 2021. Bycatch of coastal seals in Norwegian gillnet fisheries conducted by coastal fishing vessels. NAMMCO SC Working Group on Bycatch SC/28/BYCWG/04.

Nilssen, K.T. & Haug, T. (2007). Status of grey seals (Halichoerus grypus) in Norway. NAMMCO Sci. Publ. 6: 23-31. https://doi.org/10.7557/3.2719

Nilssen, K.T., Lindstrøm, U., Westgaard, J.I., Lindblom, L., Blencke, T.-R. & Haug, T. (2019). Diet and prey consumption of grey seals (Halichoerus grypus) in Norway. Marine Biology Research 15: 137-149. https://doi:10.1080/17451000.2019.1605182

North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO). (2006). Annual Report 2006. NAMMCO, Tromsø, Norway. https://nammco.no/topics/annual-reports/

North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO). (2016a). Report of the 23rd Scientific Committee Meeting, Nuuk, Greenland. https://nammco.no/topics/scientific-committee-reports/

North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO). (2016b). Report of the Committee on Hunting Methods, Oslo, Norway. https://www.nammco.no/publications/hunting-committee/

North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO). (2023a). Report of the Scientific Committee Working Group on Coastal Seals. May 2023, Copenhagen, Denmark.

North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO). (2023b). Report of the 29th Scientific Committee Meeting, Copenhagen, Denmark. https://nammco.no/topics/scientific-committee-reports/

Nowak, L.J. (2020). Observations on mechanisms and phenomena underlying underwater and surface vocalisations of grey seals, Bioacoustics, 30:6, 696-715, DOI: 10.1080/09524622.2020.1851298

Robinson, K.J., Hall, A.J., Scholl, G., Cathy Debier, Jean-Pierre Thomé, Gauthier Eppe, Catherine Adam, Kimberley A. Bennett. Investigating decadal changes in persistent organic pollutants in Scottish grey seal pups. Aquatic Conserv: Mar Freshw Ecosyst. 2019; 29( S1): 86– 100. https://doi.org/10.1002/aqc.3137

SCOS. (2021). Scientific Advice on Matters Related to the Management of Seal Populations: 2021. Sea Mammal Research Unit, St Andrews, Scotland. http://www.smru.st-andrews.ac.uk/files/2022/08/SCOS-2021.pdf

Sjöberg, M., McConnell, B. and Fedak, M. (1999), Haulout patterns of grey seals Halichoerus grypus in the Baltic Sea. Wildlife Biology, 5, 37-47. https://doi.org/10.2981/wlb.1999.007

Spaan, K.M., van Noordenburg, C., Plassmann, M.M., Schultes, L., Shaw, S., Berger, M., Heide-Jørgensen, M.P., Rosing-Asvid, A., Granquist, S.M., Dietz, R. and Sonne, C., 2020. Fluorine mass balance and suspect screening in marine mammals from the northern hemisphere. Environmental science & technology, 54(7), pp.4046-4058. http://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.9b06773

Sørmo, E.G., Skaare, J.U., Lydersen, C., Kovacs, K.M., Hammill, M.O., Jenssen, B.M. (2003).Partitioning of persistent organic pollutants in grey seal (Halichoerus grypus) mother–pup pairs.Sci Total Environ, 302, 145-155. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-9697(02)00300-5

Sørmo, E.G., Larsen, H.J.S., Johansen, G.M., Skaare, J.U., Jennsen, B.M. (2009). Immunotoxicity of Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCB) in Free-Ranging Gray Seal Pups with Special Emphasis on Dioxin-Like Congeners, Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part A, 72(3-4), 266-276, https://doi.org/10.1080/15287390802539251

Thompson, D., Hammond, P.S., Nicholas, K.S. and Fedak, M.A. (1991). Movements, diving and foraging behaviour of grey seals (Halichoerus grypus). Journal of Zoology, 224(2), 223–232. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7998.1991.tb04801.x

Vanden Berghe, M., Mat, A., Arriola, A., Polain, S., Stekke, V., Thomé, J-P, et al. (2012). Relationships between vitamin A and PCBs in grey seal mothers and pups during lactation. Environment International, 46, 6-15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2012.04.011

Víkingsson, G.A., Granquist, S.M., Gunnlaugsson, Þ., Halldórsson, S.D., Chosson, V., and Sigurðsson, G.M. (2021). ICELAND – PROGRESS REPORT ON MARINE MAMMALS IN 2020. NAMMCO/28/NPR/IS-2020-2019

Wood, S.A., Josephson E, Precoda K, Murray KT. 2022. Gray seal (Halichoerus grypus) pupping trends and 2021 population estimates in U.S. waters. US Dept Commer Northeast Fish Sci Cent Ref Doc. 22-14; 16 p.

Øigård, T.A., Frie, A.K., Nilssen, K.T. and Hammill, M.O. (2012). Modelling the abundance of grey seals (Halichoerus grypus) along the Norwegian coast. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 69(8), 1436–1447. https://doi.org/10.1093/icesjms/fss103

Institute of Marine Research (Norway) – Grey seal (in Norwegian)

Icelandic Seal Centre – Grey seal

Greenland Institute of Natural Resources – Grey seal

Fisheries and Oceans Canada – Management of the grey seal commercial hunt in Atlantic Canada

US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Fisheries – Grey seal

The Standing Senate Committee on Fisheries and Oceans – The sustainable management of grey seal populations