Common Minke Whale

Updated: June 2025

The common minke whale is the smallest of the rorquals, typically reaching a length of 8–9 metres and weighing around eight tonnes in the North Atlantic. Females are generally larger than males. Common minke whales have black or dark grey colouring on their dorsal side and white on the ventral side. A distinctive white band across the flippers is characteristic of the species in the Northern Hemisphere. With a worldwide distribution, it is the most common of the rorquals. The common minke whale feeds on a wide range of fish and invertebrates and plays an important role as a predator in the marine ecosystem.

The information presented on this page focuses on stocks within the remit of NAMMCO, including stocks shared with non-NAMMCO member countries.

Abundance

The common minke whale is the most abundant baleen whale, in the North Atlantic with an estimated population of over 220,000 in the North Atlantic (Guldborg Hansen et al., 2018; IWC; NAMMCO, 2019; NMFS, 2016; Pike et al., 2018; Solvang et al., 2021).

Distribution

Common minke whales undertake extensive seasonal migrations, moving from wintering areas in tropical or subtropical regions to higher latitude feeding areas in summer. Major summering areas include the North, Norwegian, and Barents Seas; the coastal waters of Iceland, east and west Greenland; Newfoundland and Labrador; and the northeastern coast of the USA.

Relation to Humans

In 2023, whaling activities in Norway and Greenland resulted in a total catch of 689 minke whales.

Conservation and Management

Minke whales are managed under international regimes for conservation and sustainable use by the International Whaling Commission and NAMMCO. All stocks are currently considered healthy and not threatened by current levels of human use.

The common minke whale is classified as ‘Least Concern’ on both the European regional and global IUCN Red List (2023 and 2018, respectively). It is also listed as a ‘Least Concern’ species on the national red lists of Norway (2021) and Iceland (2018).

Minke whale surfacing in calm blue sea, Bjørnøya. © George McCallum / Whalephoto.com

Scientific name: Balaenoptera acutorostrata (Lacépède, 1804). The North Atlantic common minke whale is the subspecies Balaenoptera acutorostrata acutorostrata.

Faroese: Sildreki

Greenlandic:Tikaagullik

Icelandic: Hrefna

Norwegian: Minke, Vågehval

Danish: Vågehval, sildepisker

English: Common minke whale, Northern minke whale, lesser rorqual, little piked whale, pikehead, sharp headed finner

Lifespan

Up to 50 years.

Average size

8–10 metres long and approximately nine tonnes in the Northern Hemisphere. Females are typically larger than males. For the Norwegian 2021 total catches the mean length was 743 cm with an individual length span of 450 cm – 920 cm.

Productivity

One calf probably every year from 5-8 years of age.

Feeding

‘Lunge-gulping’ behaviour is used to feed on euphausiids (krill) and a variety of shoaling fish, including herring, capelin, and cod.

Migration

Common minke whales generally migrate to high-latitude feeding areas in spring and to low-latitude breeding areas in autumn. However, some individuals may remain on feeding grounds throughout the winter.

General Characteristics

The common minke whale is the smallest species within the rorqual family (also known as the balaenopterid family). It is also the most abundant of all baleen whales in the North Atlantic.

© Marine and Freshwater Research Institute, Iceland

Males and females share a remarkably similar appearance and cannot be distinguished in the field. Females are generally larger than males, as is typical for all balaenopterids. In the North Atlantic, they typically reach lengths of 8–10 metres and weigh around nine tonnes (Gunnlaugsson et al., 2020).

At sea

The body of the common minke whale is relatively stockier compared to other rorquals. It has a sharply pointed and flat head, which has led to the nickname “pikehead.” The dorsal fin, positioned roughly two-thirds along the length of the body, is relatively tall and falcate, curving in a shape reminiscent of a sickle.

The uncommon sight of two common minke whales off Norway. Minke whales are most often seen alone in the North East Atlantic. © K.A. Fagerheim, IMR, Norway.

Common minke whales are black or dark grey on their dorsal side and white on the ventral side. They have a pale chevron (V-shaped line) on their back, just behind the head, which extends down to the flanks. A distinctive white band across the flippers is characteristic of the species in the Northern Hemisphere.

Their blow is low, rising only 2–3 metres, and is often inconspicuous and difficult to spot in the North Atlantic. Unlike some other whales, common minke whales do not raise their flukes when diving, although they do arch their backs noticeably.

Many common minke whales, especially younger animals, are inquisitive and may approach vessels. They are also capable of swimming at high speeds, over short distances up to 20 knots. From a distance, they can be mistaken for bottlenose whales or other beaked whales. However, bottlenose whales have bulbous heads and distinct beaks, whereas common minke whales have sharply triangular, flat heads. In the North Atlantic, common minke whales are typically observed alone, whereas bottlenose whales are usually seen in groups

Behaviour

In the North Atlantic, common minke whales are generally solitary., Their most distinctive behaviour is lunge feeding, where they swim at high speeds with their mouths open towards their prey. After capturing prey, they close their mouths and expel water, trapping the prey in their baleen plates.

Common minke whales do not raise their flukes when diving, but they do arch their backs prominently. They are curious by nature and may approach vessels, demonstrating impressive swimming speeds.

Like other baleen whales, common minke whales exhibit migration segregation with respect to age (length) and sex. Females tend to arrive earlier in the northern feeding areas during summer and travel further north than males (Haug et al., 2011; Horwood, 1990; Jonsgård, 1951; Laidre et al., 2009). As a result, catches early in the season and in more northern locations, such as West Greenland and Spitsbergen, tend to include a higher proportion of females than males. The historic Norwegian minke whale catches until the Moratorium (1938-1985) show a dominance of females in the Barents Sea and southern North Sea, otherwise there was a male dominance. The largest animals were also in the Barents Sea, while the coastal areas from Stadt to North Cape were inhabited by smaller individuals (Øien, 1988).

Lunge feeding common minke whale off Iceland. © Marine and Freshwater Research Institute, Iceland.

Listen to their calls off Eastern Canada (NOAA)

Life history

Common minke whales reach sexual maturity at 5–7 years of age (Haug et al., 2011; NAMMCO, 1999) and can live up to 42 years in the North Atlantic (Audunsson et al., 2013). They are essentially annual breeders, with most mature females becoming pregnant each year. Mating takes place in late winter, and gestation lasts about 10 months, with calves born in low-latitude regions during the winter (Martin et al., 1990).

Although the mating strategies of common minke whales remain poorly understood, evidence suggests sexual segregation during the summer months, with females dominating at higher latitudes This behaviour has implications for management, as females constitute a significant proportion of the catch in northern regions. For instance, in the coastal West Greenland harvest, females make up approximately 71–78% of the catch (Laidre et al., 2009), and in the recent Norwegian catches the proportion of females is around 70%.

Feeding

Common minke whales feed on a wide variety of fish and invertebrates. In the North Atlantic, their diet primarily consists of krill (Thysanoessa spp. and Meganyctiphanes spp.), Atlantic herring (Clupea harengus), capelin (Mallotus villosus), sandeels (Ammodytidae), cod (Gadus morhua), polar cod (Boreogadus saida), haddock (Melanogrammus aeglefinus), and other fish and invertebrate species (NAMMCO, 1998). The diet varies by location and over time.

In the Northeast Atlantic, krill dominate the diet in far northern areas, while capelin, herring, and haddock become more prominent further south in the Norwegian Sea and along coastal Norway. Sandeels and mackerel (Scomber scombrus) are commonly eaten in southern areas such as the North Sea (Haug et al., 2002; Windsland et al., 2007). However, recent research suggests an increasing reliance on krill and demersal fish, such as gadoids, in the northern Barents Sea, likely driven by ecosystem changes due to climate warming (Haug et al., 2024). In the Central Atlantic, capelin constitutes a significant portion of the diet, alongside herring, sandeels, and cod (Víkingsson et al., 2013). Interannual variations in diet composition, likely reflecting prey availability, have been observed in the Northeast Atlantic (Haug et al., 2002; Windsland et al., 2007) and around Iceland (Víkingsson et al., 2013).

A series of ecological studies conducted over the past 30 years has examined how fluctuations in the stocks of key pelagic fish species, such as capelin and herring, influenced the diet and food consumption of minke whales in the Barents Sea. During periods of low capelin and herring abundance, such as the capelin stock collapse in 1992–1993, minke whales adapted by consuming alternative prey like krill. These studies highlighted the whales’ flexible feeding habits and their ability to switch prey based on availability, with krill dominating diets in higher latitudes and herring and capelin being more prominent further south. These findings are crucial for understanding minke whale foraging behaviour and ecosystem dynamics.

areas in a lean condition but accumulate blubber rapidly during the summer. Blubber accumulation has been shown to reflect prey availability and ecosystem health, with notable fluctuations in thickness linked to prey dynamics such as Northeast Arctic cod stocks (Solvang et al., 2022). Using data from whales taken during Iceland’s common minke whale harvest, Christiansen et al. (2013) estimated that mature common minke whales accumulate around 0.5 cubic metres—nearly half a tonne—of blubber over the summer feeding season. This blubber serves as an energy reserve for migration and reproduction in southern regions, where food is less abundanT.

Multi-species interactions

Common minke whales play a significant role as predators in the marine ecosystem, particularly in the Northeast and Central Atlantic stock areas. They are estimated to consume over 1.8 million tonnes of prey annually in the northern Northeast Atlantic stock area (NAMMCO, 1998), much of which includes commercially important fish species such as herring, cod, and haddock. This level of consumption is comparable to the total commercial fishery for pelagic fish in the area (Toresen et al., 1998).

In Icelandic shelf waters, common minke whales are the most significant marine mammal predators of fish, consuming about one million tonnes of fish annually (Sigurjónsson & Vikingsson, 1997). Multispecies modelling has suggested that this level of consumption may have important implications for commercial fisheries in the Northeast and Central Atlantic (NAMMCO, 1998; Stefánsson et al., 1997). However, such modelling is still in its early stages.

The effects of multi-species interactions can sometimes be counterintuitive. For instance, Lindstrøm et al. (2009), using a multi-species model for the Barents Sea including cod, capelin, herring, and common minke whales, found that increased predation by common minke whales could positively affect capelin stocks. Although capelin is a major prey species for common minke whales, the whales also consume cod, which are significant predators on capelin. Dietary shifts observed in the Barents Sea towards krill and demersal fish further underscore the complexity of these interactions under changing environmental conditions (Haug et al., 2024).

Predation

Common minke whales are preyed upon by humans, killer whales (Orcinus orca), and potentially by large sharks in southern regions. Numerous instances of killer whale predation have been observed (e.g., Ford et al., 2005). Pods of killer whales begin their hunt by chasing common minke whales at speeds of 15–30 km/h. In most cases, common minke whales can maintain these speeds for longer periods than killer whales, eventually outdistancing them. However, if a common minke whale is confined in a bay or unable to escape, the killer whales kill it by ramming it repeatedly or holding it underwater (Ford et al., 2005). The extent of killer whale predation on common minke whales and its impact on their population is not yet known.

Parasites and Epibiotics

Common minke whales are hosts to various internal and external parasites, as well as commensals and epibiotic organisms. In waters off Iceland, more than half of the whales show evidence of attacks by sea lamprey (Petromyzon marinus). Approximately 10% of the population is affected by copepods such as Caligus elongatus and Pennella balaenopterae. Other observed epibiotic organisms include the whale louse (Cyamus balaenopterae), the pseudo-stalked barnacle (Xenobalanus globicipitis), and the goose barnacle (Conchoderma auritum) (Ólafsdóttir & Shinn, 2017).

Distribution

Like other baleen whales, common minke whales undertake extensive seasonal migrations, moving from wintering areas in tropical or subtropical regions to higher latitude feeding areas in the summer (Horwood, 1990). The wintering areas are not documented, but satellite tagging during autumn migrations suggests that common minke whales that summer in the northeast Atlantic and around Iceland spend winter in the southern North Atlantic at latitudes below 30°N (IWC, 2014a; Víkingsson & Heide-Jørgensen, 2014). Summering areas are well known from past whaling activities and more recent surveys.

Major summering areas in the North Atlantic include the North, Norwegian, and Barents Seas; the coastal waters of Iceland; east and west Greenland; Newfoundland and Labrador; and the northeastern coast of the USA. Recent research highlights significant distributional changes in response to climate-driven prey shifts. For instance, studies in the Barents Sea suggest that minke whales expand northwards, reflecting the ongoing borealization of Arctic ecosystems (Haug et al., 2024). In some regions, common minke whales appear to be extending their summer range northwards. Sightings in Arctic Canada have been reported in recent decades in areas where they were previously unknown to local residents (Higdon & Ferguson, 2011). Additionally, there has been an increase in catches by northern communities in west Greenland (NAMMCO, 2012b). Recent Norwegian surveys in the northeast Atlantic also suggest significant distributional shifts northwards and eastwards (NAMMCO, 2018). A habitat modelling study (Sun et al., 2022) project further changes in minke whale distribution under future climate scenarios, with a contraction of suitable habitat for North Atlantic populations due to warming, while the North Pacific population may experience an expansion. Distributional changes in the Barents Sea are likely in response to shifts in prey distribution, which may themselves result from a warming marine climate in the region (Haug et al., 2017). This aligns with findings that prey species, such as capelin and krill, are undergoing northward expansions, significantly altering the feeding grounds available to minke whales (Haug et al., 2024).

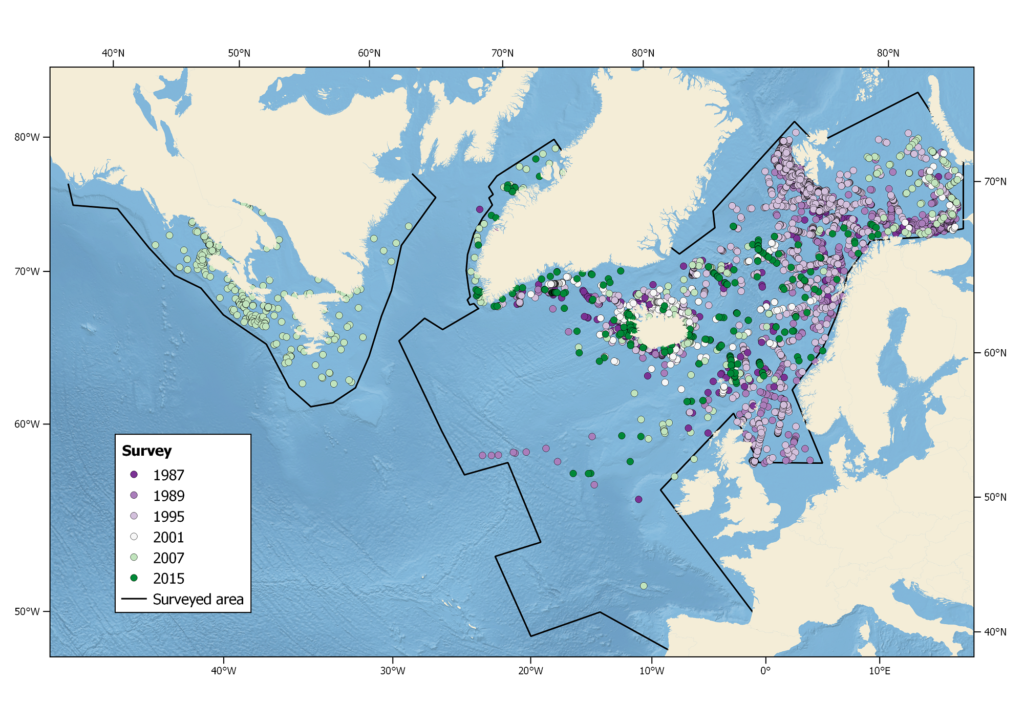

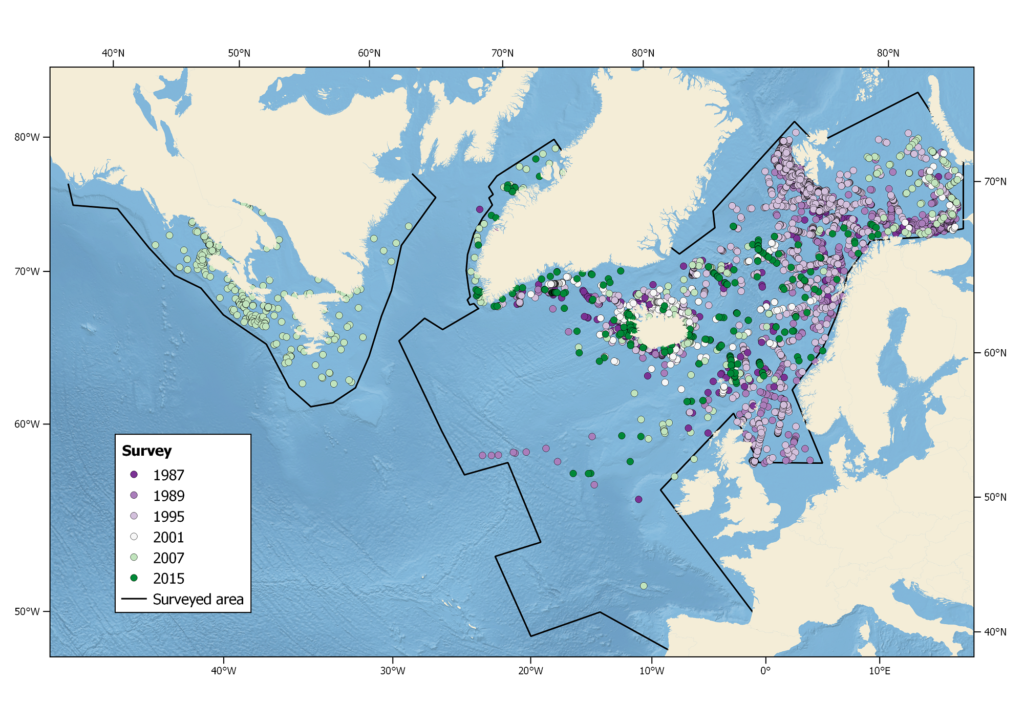

Summer distribution (June-August) of common minke whales in the North Atlantic, showing sightings from dedicated cetacean surveys in the North Atlantic over the period 1987-2015. Included are the 2007 CODA and SNESSA surveys. The outer boundary of the survey area is indicated. Not all areas were surveyed each year.

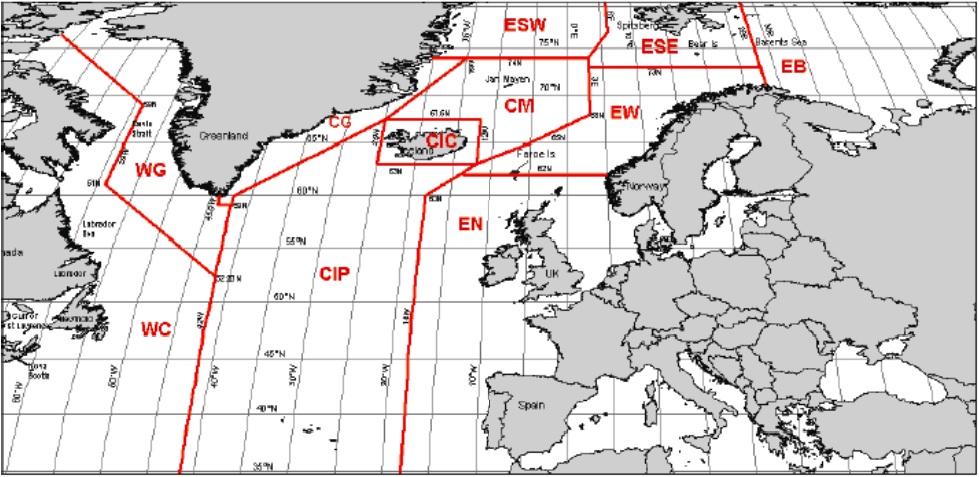

Management stocks

North Atlantic common minke whales have been divided into three management regions (referred to as “medium areas”) by the International Whaling Commission (IWC) (Donovan, 1991): the Northeast Atlantic (medium area E including the Barents, Norwegian, and North Seas), the Central Atlantic (medium area C covering waters around Jan Mayen, Iceland, and East Greenland), and the Western Atlantic (medium area W including West Greenland and the Canadian East Coast). The medium areas are further divided into smaller sub-stock areas, referred to as “small areas.” However, the original stock and sub-stock divisions were not based on extensive biological data, and recent genetic analyses have not provided clear evidence of stock structure among common minke whales in the North Atlantic (IWC, 2014a, b).

The NAMMCO Scientific Committee considers it likely that there is only one breeding stock of common minke whales in the North Atlantic. However, for management purposes, NAMMCO has agreed to use three management regions – Western Atlantic, Central Atlantic, and Northeast Atlantic – each of which is divided into smaller sub-areas (management units). Using these smaller sub-area boundaries is considered a conservative management approach, as it reduces the risk of overexploitation in any one area. Recent genetic studies have supported the idea of a panmictic population across the Northeast Atlantic, but further research is needed to conclusively confirm stock structure at finer scales (Øien et al., 2024).

Migration

The migratory pattern of North Atlantic common minke whales—wintering in tropical waters and summering at high latitudes—is similar to that of other baleen whales in both the northern and southern hemispheres (Horwood, 1990). As a result, the distributions of northern and southern hemisphere populations generally do not overlap. However, Antarctic minke whales (Balaenoptera bonaerensis), a species distinct from the common minke whale, have occasionally been found in the North Atlantic. Glover et al. (2010) analysed DNA profiles from minke whales taken during the Norwegian hunt and discovered that one Antarctic minke whale was taken in 1996, and a hybrid between the two species was recorded in 2007.

Recent habitat modeling suggests that climate change could influence the migratory and distributional patterns of North Atlantic minke whales, with potential reductions in habitat suitability in their wintering areas (Sun et al., 2022). Additionally, shifts in prey availability due to borealization in Arctic ecosystems may affect migratory timings and routes (Haug et al., 2024). While such occurrences are likely very rare, they indicate that the hemispheric populations of whales are not as isolated from one another as previously thought.

Estimates of the abundance of common minke whales, as well as other whale species in the North Atlantic, have primarily been derived from sightings surveys conducted from ships and aeroplanes to cover their summer feeding grounds. The North Atlantic Sightings Surveys (NASS) provide a time series of abundance estimates spanning from 1987 to 2015, covering a large portion of the North Atlantic. Norwegian “mosaic” surveys (NILS) cover most of the northeast Atlantic, with a portion of the area surveyed annually on a six-year rotation. Variation in distribution from year to year is accounted for in the variance of the resulting combined abundance estimates (Skaug et al., 2004). The most recent NASS survey was conducted in 2024 (results expected to be available in 2026) and will prolong the time series by nearly ten years. This will contribute to our understanding of minke whale trends in abundance.

Additional surveys, including the European SCANS and CODA surveys, the Canadian component of T-NASS 2007, NASS 2016, and American SNESSA surveys, have further contributed to our understanding of the abundance and distribution of common minke whales. Available abundance estimates by stock area are provided in the table below.

Abundance of minke whale in the North Atlantic from NASS and associated surveys

For definition of stocks see the above map; CMA, IWC Central Medium Area, with putative stock boundaries; A/S, aerial or shipboard surveys; Bias, correction bias: - a, availability and p, perception; CI, confidence interval. CA, Canada; GL, Greenland.| Areas | Stock | Year/Survey | A/S | Abundance | Bias | CV | 95% CI | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canadian East Coast | Newfoundland/Labrador | 2007/NASS | A | 4,020 | a.p | 0.43 | N/A | Lawson and Gosselin (2018) |

| 2016/NASS | A | 13,008 | a.p | 0.46 | N/A | |||

| Nova Scotia/Gulf of St. Lawrence | 2007/NASS | A | 12,412 | a.p | 0.37 | N/A | ||

| 2016/CA | A | 6,158 | a.p | 0.40 | N/A | |||

| West Greenland | WG | 1993/GL | A | 8,371 | a | 0.43 | 2,414–16,929 | Larsen (1995) |

| 2005/GL | A | 10,792 | a.p | 0.59 | 3,594–32,407 | Heide-Jørgensen et al. (2008) | ||

| 2007/NASS | A | 9,066 | a.p | 0.39 | 4,333–18,973 | Hansen et al. (2018) | ||

| 2015/NASS | A | 5,095 | a.p | 0.46 | 2,171–11,961 | |||

| East Greenland | CG | 2015/NASS | A | 2,762 | a.p | 0.47 | 1,160-6,574 | |

| Central Atlantic | CIC | 1987/NASS | A | 24,532 | a | 0.32 | 13,399–44,916 | Borchers et al. (2009) |

| 2001/NASS | A | 43,633 | a.p | 0.19 | 30,148–63,149 | |||

| 2007/NASS | A | 20,834 | a.p | 0.35 | 9,808–37,042 | Pike et al. (2020b) | ||

| 2009/IS | A | 9,588 | a.p | 0.24 | 5,274–14,420 | |||

| 2016/IS | A | 13,497 | a.p | 0.50 | 3,312–55,007 | |||

| CM | 1997/NILS | S | 26,718 | a.p | 0.14 | 20,333–35,107 | Skaug et al. (2004) | |

| 2005/NILS | S | 24,890 | a.p | 0.45 | 10,727–57,751 | IWC (2010) | ||

| 2008–2013/NILS | S | 10,991 | a.p | 0.36 | 4,498–35,911 | Solvang et al. (2015) | ||

| 2014–2019 | S | 37,020 | a.p. | 0.26 | N/A | Solvang et al. (2021) | ||

| CMA | 2015/NASS | S | 48,016 | p | 0.23 | N/A | Pike (2018) | |

| Northeast Atlantic | NEA (ESW + ESE + EB + CM + EW + EN | 1988–89/NASS | S | 67,380 | p | 0.19 | 44,060–92,181 | Schweder et al. (1997) |

| 1995/NILS | S | 118,299 | a.p | 0.10 | 92,213–136,337 | |||

| 1996–2001/NILS | S | 107,205 | a.p | 0.13 | 83,180–138,169 | Skaug et al. (2004) | ||

| 2002–2007/NILS | S | 108,140 | a.p | 0.23 | 69,299–168,752 | Bøthun et al. (2009) | ||

| 2008–2013/NILS | S | 100,615 | a.p | 0.11 | 81,154–124,743 | Solvang et al. (2015) | ||

| 2014–2019 | S | 149,722 | a.p. | 0.15 | N/A | Solvang et al. (2021) |

Canadian East Coast

Recent estimates indicate an abundance of more than 20,000 common minke whales in this area. As there has been no recent hunting and no other known threats to the population, there is currently no conservation concern. However, recent studies highlight the need to monitor the potential impacts of climate-driven habitat shifts and changes in prey availability, which could influence the long-term stability of the population (Sun et al., 2022).

West Greenland

estimates for West Greenland. These suggest that abundance initially increased until 2007 but then dropped to the lowest recorded level in 2015. Evidence suggests that common minke whales caught off West Greenland may be part of a more widespread stock, particularly given the high proportion of females in the catch (Laidre et al., 2009). Consequently, it is challenging to assess the status of the overall stock using data solely from surveys in West Greenland.

There may also be some exchange between East and West Greenland populations, which could explain the observed fluctuations (IWC, 2018). The IWC Scientific Committee has advised that an annual take of up to 164 whales will not harm the stock, and recent harvest levels have been below this threshold.

Central Atlantic

Five abundance estimates for the Central Atlantic’s CM sub-region are available from surveys conducted between 1987 and 2015. These show an upward trend from 1989 to 1997, stabilisation until 2005, followed by a decrease in the 2008–2013 surveys. Numbers increased again in 2015 and were even higher in 2016 (Solvang et al., 2021). This pattern suggests large-scale shifts in distribution between this sub-area and adjacent regions. Given the low level of harvest and the absence of evidence for a long-term decline in numbers, there is no conservation concern for common minke whales summering in this area.

Recent changes

The coastal area around Iceland, designated as the CIC sub-region of the Central Atlantic, has been surveyed five times since 1987, most recently in 2016. Recent estimates (2007 to 2016) are more than 50% lower than earlier ones (Pike et al., 2020). The reasons for this decline are unclear, as Icelandic whaling has only recently resumed at levels too low to account for such a reduction.

Possible explanations include:

- Changes in seasonal migration, with whales arriving in the area later than in previous years.

- Changes in spatial distribution, with whales that previously summered in this region moving elsewhere.

The second explanation seems most likely, as significant changes in oceanographic conditions and the distribution of key prey species, such as sandeels and capelin, have been observed in Icelandic waters (Víkingsson et al., 2015). These changes may have affected the distribution of common minke whales. New habitat modelling supports the hypothesis of northward shifts in summer distributions in response to borealization of the ecosystem, further emphasising the need for expanded surveys in previously unstudied areas (Sun et al., 2022).

Northeast Atlantic

Six abundance estimates for the Northeast Atlantic (Medium Area E) are available from surveys conducted between 1989 and 2019. These range from a low of 64,730 (CV=0.19) in 1989 to a high of 112,125 (CV=0.10) in 1995. Although fluctuations in abundance over the years, seen overall, the six estimates show an increasing trend, although not significant. However, more important are the distributional changes seen within the area: Over the recent three survey periods the summer abundance in the Barents Sea has doubled while it has been halved within the Norwegian Sea. At the same time there has also been a decrease in the Spitsbergen area. It is reasonable to assume that these movements are due to changes in the availability of prey and are under further investigations.

There is no evidence of a long-term increase or decrease in abundance between 1989 and 2019. In recent years, the basic total Norwegian annual quotas have remained steady at approximately 880 whales (for Area CM+E), while actual catches have been 537 whales/year (for Area E) the past 20 years and show a decreasing trend. For actual numbers regarding catches and quotas, click here. Although neither NAMMCO nor the IWC has assigned a specific conservation status to this stock, it is likely to be in a healthy state. The population is large relative to both present and historic harvests, with no evidence of a decline. Proposals for improved monitoring, including genetic mark-recapture and expanded survey coverage, have been made to ensure long-term sustainability under changing environmental conditions (Øien et al., 2024).

Management

The common minke whale is managed by the International Whaling Commission (IWC) and NAMMCO. NAMMCO provides scientific advice on stock status, sustainable harvest levels, and conservation proposals to member governments. Recently, NAMMCO has focused on the Central Stock at Iceland’s request.

In 2011, the NAMMCO Scientific Committee concluded that annual removals of up to 229 common minke whales from the CIC area around Iceland were safe and precautionary (NAMMCO, 2012a). In 2015, this advice was revised to allow annual removals of up to 224 whales until 2018 (NAMMCO, 2015). A further review in 2017 determined that annual catches of up to 217 whales would be safe for the period 2018–2025 (NAMMCO, 2017). This advice is considered conservative, as it assumes the CIC sub-area functions as a closed stock, whereas it is likely part of a larger North Atlantic population. Recent research indicates the importance of considering shifts in prey availability and distribution caused by climate change, which may affect stock connectivity and the reliability of abundance estimates (Haug et al., 2024).

NAMMCO

NAMMCO operates the only intergovernmental observation programme for marine mammal hunts: the NAMMCO Observation Scheme for the Hunting of Marine Mammals. This scheme collects reliable information on marine mammal hunting activities in member countries and ensures that NAMMCO recommendations and national regulations are adhered to.

NAMMCO appoints independent observers, typically from outside the country being observed, to monitor hunting and inspection activities. Observers may join whaling vessels to oversee hunts, check safety and maintenance of the equipment, check licences and certificates, inspect whaling logbooks, and visit landing and processing facilities. Reports from observers are submitted directly to the NAMMCO Secretariat.

Scientific advice

In 2015, the NAMMCO Scientific Committee concluded that annual removals of up to 224 common minke whales from the CIC area were sustainable until 2018 (NAMMCO, 2015). This advice was revised in 2017, with the recommendation that catches of up to 217 whales would remain precautionary for 2018–2025 (NAMMCO, 2017). Recent catches in this area have been much lower, ranging from 24 to 81 whales annually since hunting resumed in 2003.

IWC

The International Whaling Commission (IWC) introduced quotas on North Atlantic minke whales in the 1970s and implemented a temporary moratorium on commercial whaling taking effect from 1986. However, Norway is not subject to this moratorium, having lodged a formal objection under the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling. Greenland continues to hunt common minke whales under “Aboriginal Subsistence” quotas, which are exempt from the moratorium. Iceland ceased hunting common minke whales in 1985, withdrew from the IWC in 1992, and rejoined in 2003 with an objection to the moratorium.

Although the IWC provides scientific advice on the stocks hunted in the North Atlantic, it does not regulate commercial whaling by Norway or Iceland, as this is incompatible with the moratorium.

Aboriginal Subsistence Whaling

The IWC manages Aboriginal Subsistence Whaling in Greenland. Strike limits are based on scientific advice about sustainability and the cultural and nutritional needs of Indigenous communities. The main objectives are:

- Ensuring extinction risk is not significantly increased.

- Allowing harvests to meet cultural and nutritional needs sustainably.

- Maintaining or increasing stocks to their highest net recruitment levels.

Greenland has requested 666 tonnes of whale meat annually, with minke whales contributing about half of this total. In 2024, the IWC reaffirmed its commitment to managing Aboriginal Subsistence Whaling, ensuring that Indigenous communities’ needs are met while protecting whale populations. At the 69th Meeting of the International Whaling Commission (IWC69) held in Lima, Peru, discussions highlighted the importance of balancing cultural and nutritional requirements with sustainability. Greenland’s request for an annual quota of 666 tonnes of whale meat, including minke whales, continues to be supported under scientifically advised strike limits. This approach ensures that subsistence whaling practices do not compromise conservation objectives or harm whale populations.

The Revised Management Procedure

While the IWC does not currently set catch limits for commercial whaling, it developed the Revised Management Procedure (RMP) in 1994. The RMP has three main objectives:

- Establishing stable catch limits.

- Prohibiting catches from populations below 54% of their original size.

- Maximising sustainable yield within conservation limits.

The RMP uses a Catch Limit Algorithm (CLA) to calculate quotas based on abundance estimates, uncertainty, and historical catches. While the IWC has not implemented the RMP for commercial whaling, the Scientific Committee continues to refine it, and Norway uses it to set national quotas.

Iceland

Iceland sets its common minke whale quotas based on NAMMCO advice. Recent quotas have been around 200 whales annually, though actual catches have been significantly lower. In 2019, a quota of 217 whales was confirmed for the period 2018–2023.

Icelandic regulations require gunners to complete training in handling and firing grenades and harpoons and hold a general firearms licence for backup weapons. Other regulations govern the type of equipment used. Hunters must report the sex, length, and location of each whale taken to the Directorate of Fisheries. Inspectors carry out random, unannounced checks on whaling vessels.

Iceland also maintains a DNA registry, modelled after Norway’s, to monitor the catch.

Norway

Minke whale surfacing in calm blue sea, Bjørnøya. © George McCallum / Whalephoto.com

The Norwegian Ministry of Trade, Industry and Fisheries sets common minke whale quotas for six-year periods based on the modified Revised Management Procedure (RMP) implemented by the IWC Scientific Committee for North Atlantic minke whales. This system determines an annual sustainable removal level for the entire Norwegian area, then allocates specific quotas to different management areas based on the abundance in each.

If the full annual quota is not taken, unused quotas can be carried over and added to the next year’s quota (the “carry-over system”). The whaling season starts primo April and ends medio September, however, most of the whaling activity takes place in May and June. The average annual catch in the past 20 years is about 540 whales and showing a decreasing trend. The catch in 2024 was 415 whales. For actual numbers regarding catches and quotas, click here.

Equipment regulation

Norway regulates the equipment used in common minke whale hunting to ensure hunter safety and minimise animal suffering. Regulations specify the size and type of harpoon guns, grenade types and charges, the minimum calibre and type of secondary rifles, and other required equipment. Prospective whalers and gunners must pass an obligatory training course, including a shooting proficiency test, to obtain a licence (NAMMCO, 2011).

To further ensure compliance with regulations and ethical hunting practices, the Director of Fisheries monitors the use of penthrite grenades by comparing the number purchased with the number used and the number of whales caught. This oversight helps verify that hunting activities align with approved quotas and ensures accountability among whalers.

Electronic monitoring system

Norway has largely replaced human inspectors with an electronic monitoring system to independently oversee whaling activities (NAMMCO, 2004, 2005, 2011a). Fully implemented in 2006, the “blue box” system consists of a control and data logger that monitors hunting activity independently. The use of this system was stopped from the 2023 season onward. This decision was made due to a combination of high operational costs, technical challenges, and the limited added value of the system compared to the existing monitoring regime. The small size and design of many whaling vessels also made the installation and maintenance of the system increasingly difficult. Norwegian authorities concluded that the current system of independent observers, mandatory reporting, and random inspections by the Directorate of Fisheries provided sufficient oversight.

The unit, which was sealed and tamper-proof, uses an independent GPS to log time and position data, alongside sensors such as shot transducers, strain transducers, and heel sensors. These detect when and where a whale was shot and brought on board. The system could operate without maintenance for up to four months, with data encrypted for security. After the hunting season, the encrypted data was retrieved, decrypted, and analysed by authorised personnel in the Directorate of Fisheries. In addition, Fisheries Directorate inspectors conduct periodic random checks of hunting activities.

DNA registry

Norway ensures the legitimacy of the harvest through the world’s first wildlife DNA registry. A sample is taken from every legally harvested minke whale. The analysis of 12 DNA loci creates a unique “fingerprint” for individual whales. Meat and other products can then be sampled to confirm they originate from legally taken whales.

The effectiveness of this system was demonstrated in a study that tested market products and samples from two beached whales. All market products were identified as originating from legally caught whales, while the samples from the beached whales did not match the DNA registry (Palsbøll et al., 2006).

Hunting and Utilisation

Whaling has been practised in the North Atlantic for thousands of years, but commercial hunting specifically targeting common minke whales is relatively recent (Kalland, 1995; Sigurjónsson, 1997). This form of whaling (‘small-type whaling’) began in the 20th century in Norway, Iceland, Greenland, and Canada, primarily conducted on a small scale by fishers using small vessels as a supplement to their fishing activities. The primary product from common minke whale hunts has always been meat for human consumption. Today, common minke whaling in the North Atlantic is conducted by only three countries: Norway, Iceland, and Greenland.

Greenland

Collective common minke whale hunt in Greenland. © F. Sejersen

Greenland primarily hunts common minke whales from the West Greenland stock, with a smaller proportion taken from the Central stock by East Greenlanders. Over the past decade, catches have remained stable, ranging from 140 to 200 whales annually – in 2023 the catches were 164 animals off West Greenland and 18 animals off East Greenland. This hunt is categorised as “Aboriginal Subsistence Whaling” and is not affected by the IWC moratorium on commercial whaling.

The hunt

Greenland’s hunting methods are partly similar to those used in Norway: Around 40–50 vessels equipped with harpoon cannons hunt common minke and larger whales (Greenland, 2018). In addition, 20–30% of the quota is hunted using collective rifle hunts, primarily in isolated communities lacking harpoon-equipped vessels, such as those north of Disko Bay and in East Greenland.

In collective hunts, hunters use small boats to drive whales into shallow waters, where they are easier to retrieve. The whale is then slowed with non-lethal shots before being harpooned and secured with floats to prevent it from sinking. Once secured, it is killed with rifle shots to the brain (Larsen & Hansen, 1997; NAMMCO, 2011).

Whales killed in collective hunts are towed ashore and butchered on the beach. Similarly, vessels participating in harpoon hunts may bring whales ashore for processing if they lack onboard facilities.

Time to death

Between 2007 and 2011, median TTD for Greenlandic harpoon hunts was 1 to 5 minutes, with 20% of whales dying instantly or within one minute. In contrast, the instantaneous death rate in Norwegian hunts is 80% (Greenland, 2012; NAMMCO, 2011). The reasons for this difference may include monitoring methods, weapon quality, and hunter training.

In collective hunts, where whales must be secured with several harpoons before being killed, TTD ranged from 20 to 25 minutes. This approach balances the need to prevent struck-and-lost rates, which averaged 6% from 2007 to 2011, against the goal of instantaneous kills (NAMMCO, 2007).

Use

Onshore processing of common minke whale in Greenland. © F. Sejersen

In Greenland, common minke whale meat is a valued food, with the skin and subcutaneous fat (mattak) and ventral grooves (qiporaq) considered delicacies. Baleen and bones are sometimes used for crafts. Greenland consumes approximately 340 tonnes of common minke whale meat annually, making it the largest source of whale meat in the country (Greenland, 2012).

Historically, catches were shared among hunters and their communities according to traditional rules (Inuktitut ningiqtuq, Greenlandic ningerpoq), ensuring that everyone received a portion (Wenzel, 1995; Sejersen, 2001). Today, some whale products are sold in open-air markets (Kalaalimineerniarfik) and supermarkets, providing essential income to hunters and supplying meat to areas with limited local access.

Iceland

Whaling in Iceland dates back to medieval times, with various species hunted for food. The term hvalreki (a stranded whale) is synonymous with good fortune in Icelandic. Modern whaling began in the late 1800s, primarily targeting blue and fin whales. Common minke whaling developed in the early 20th century as a seasonal occupation for fishers.

Before 1950, catches of common minke whales were small, averaging 50 annually, and primarily consumed domestically (Sigurjónsson, 1989). By the mid-20th century, export markets, particularly to Japan, became more significant, increasing catches to 200 annually before the IWC moratorium in 1986. Common minke whaling resumed under a Scientific Permit in 2003 and as commercial whaling in 2006. Since then, 40–80 whales have been hunted annually, primarily in coastal waters of the CIC sub-area of the Central Stock until 2019 when no catches of minke whales were made.

The Icelandic Minke Whale Research Program. Sampling of stomach content. © Marine and Freshwater Research Institute, Iceland.

Icelandic vessels use harpoon cannons with penthrite grenades, similar to those used in Norway. Whales are processed at sea.

A study of Time of Death (TTD) data from the 2014 and 2015 seasons was inconclusive due to a small sample size (NAMMCO, 2015). However, the efficiency of Icelandic hunts is assumed to be comparable to Norwegian standards (NAMMCO, 2011).

Use

Since hunting resumed in 2003, all common minke whale products have been consumed within Iceland. Once a staple food, whale meat became scarce after the cessation of whaling in 1986. Today, it is available in butcher shops, supermarkets, and restaurants and is prepared like other meats.

A traditional Icelandic delicacy is hvalrengi, ventral groove blubber pickled in sour milk (súrmatur), a preservation method unique to Iceland (Sigurgeirsson, 2001).

In 2019, for the first time since 2003, no common minke whales were hunted in Iceland. The primary whaling company, IP útgerð, focused on harvesting sea cucumbers and imported minke whale meat from Norway instead (Kyzer, 2019).

Norwegian common minke whaling with a harpoon cannon and explosive harpoon head. © T. Haug, IMR, Norway.

Norway

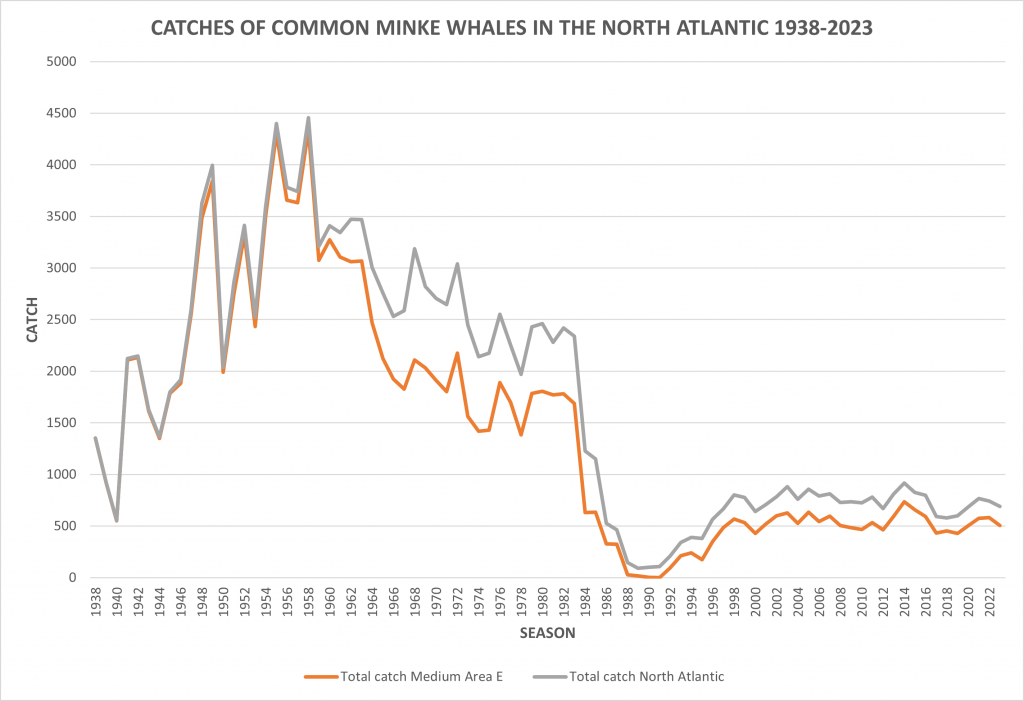

The Norwegian commercial minke whaling started around 1920 and developed quite quickly into a comprehensive coastal fishery. In 1938 a licensing system was introduced giving information on all whales caught since then. In 1938, 260 vessels were involved with the whaling – mostly small fishing boats with a mean length of about 45 feet. Through the years the number of participating vessels decreased, and their mean length increased to respectively around 80 vessels and about 70 feet length in the early 1980ies. Minke whaling was originally coastal but moved early on into the Barents Sea and Spitsbergen area and reached its peak in the mid 1950ies with total annual catches of around 4300 whales. This triggered a strong competition between the whalers and resulted in a westward expansion of the Norwegian minke whaling to include waters of the Central stock and West Greenland area, and even Canadian waters were explored. Following the introduction of Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ, formally adopted by UNCLOS 1982), whaling areas were limited to Norwegian waters.

The recent Norwegian catches primarily come from the Northeastern stock area, with a smaller proportion taken from the Central stock area around Jan Mayen. Historically, Norway also took common minke whales from the West Greenland stock area until 1986. Norwegian whalers have caught the largest share of the recorded minke whale catches in North Atlantic.

Catches of common minke whales in the North Atlantic 1938-2023. Catches in Medium Area E (Northeast Atlantic) have been taken by Norwegian whalers.

Before the International Whaling Commission (IWC) moratorium on commercial whaling in 1986, annual catches in Norway were between 1500 and 2,000 whales. Although Norway lodged a formal reservation to the moratorium and was not legally bound by it, commercial whaling was temporarily halted from 1988 to 1992. During this period, a large research program on marine mammals was conducted and only scientific research whaling was allowed. Commercial whaling resumed in 1993, and recent catches have ranged from 500 to 700 whales annually

The hunt

Norwegian whaling is conducted from fishing vessels that are equipped for whaling during the spring and summer but are used for fishing during the rest of the year. These vessels are fitted with 50 mm or 60 mm harpoon cannons, which use a gunpowder charge to fire harpoons.

The harpoons are of the “hot” type, equipped with explosive grenades containing 30 grams of penthrite. The grenades are designed to detonate inside the whale, aiming to kill the animal as quickly as possible to minimise suffering. A line attached to the harpoon secures the whale and prevents it from being lost, and the animal is hauled aboard using a winch (NAMMCO, 2011).

Flensing of a minke whale onboard a Norwegian vessel (1994). © B.T. Forberg, IMR, Norway.

The harpooner typically aims for the whale’s thorax region, shooting from the side. A large-calibre rifle serves as a secondary method if required, though this is usually unnecessary. The instantaneous death rate (IDR) from the harpoon shot alone was over 80% in 1,667 hunts monitored between 2000 and 2002 (NAMMCO, 2011). In 2011 – 2012 , further data collection showed an IDR of 82%. Most of the remaining whales died within a few minutes, with only a small proportion requiring a second harpoon shot or dispatch with a rifle shot to the brain. Once secured, the whale is flensed onboard. Meat and other products are cooled in the open air on deck before being stored on ice for transport to port.

Hunting methods

Norway has conducted extensive research to improve methods of killing whales, aiming to make the process as quick and humane as possible. It is the only country to undertake such research in modern times. A significant focus has been on developing and refining the explosive penthrite grenades used in hunts, which replaced earlier non-explosive “cold” harpoon heads.

The penthrite grenade was initially developed and deployed in 1986, and its refinement is ongoing. The use of these grenades has increased the IDR to over 80%, compared with just 17% with cold harpoons, and significantly reduced the average time to death. Post-mortem studies of killed whales are used to determine the cause of death and provide hunters with information to further improve their techniques.

Export

Norway previously exported whale meat and blubber, mainly to Japan, but this trade ceased in 1983 following a trade ban on whale products under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). While Norway held a reservation against this decision, it voluntarily stopped exporting whale products.

In 2001, Norway allowed exports to resume, resulting in a minor international trade, particularly with Japan. However, the majority of whale products are consumed domestically. Whale meat is sold fresh or frozen in grocery stores, butcher shops, restaurants and fish markets across Norway, particularly along the western and northern coast. Some meat is also processed into products such as sausages and burgers. Recent evaluations suggest that the domestic market for whale products remains stable, but ongoing monitoring of consumer trends and international trade regulations is essential (Øien et al., 2024).

Map of the North Atlantic showing the sub-areas defined for the North Atlantic common minke whales. The E area for Norway in the database below is a compilation of the catches in the EB, EN, ES and EW sub-areas.

Catches in NAMMCO member countries since 1992

| Country | Species (common name) | Species (scientific name) | Year or Season | Area or Stock | Catch Total | Quota (if applicable) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iceland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 1992-2002 | Iceland Coastal (CIC) | 0 | |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2024 | E | 415 | 904 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2024 | C | 0 | 253 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2024 | Total | 415 | 1157 |

| Iceland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2024 | Iceland Coastal (CIC) | 0 | 260 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2023 | E | 507 | 747 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2023 | C | 0 | 253 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2023 | Total | 507 | 1000 |

| Iceland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2023 | Iceland Coastal (CIC) | 0 | 260 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2023 | West | 164 | 188 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2023 | East | 18 | 24 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2022 | E | 581 | 664 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2022 | C | 0 | 253 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2022 | Total | 581 | 917 |

| Iceland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2022 | Iceland Coastal (CIC) | 0 | 260 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2022 | West | 146 | 206 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2022 | East | 17 | 21 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2021 | E | 577 | 1108 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2021 | C | 0 | 170 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2021 | Total | 577 | 1278 |

| Iceland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2021 | Iceland Coastal (CIC) | 1 | 260 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2021 | West | 167 | 219 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2021 | East | 21 | 22 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2020 | E | 503 | 1108 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2020 | CM | 0 | 170 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2020 | Total | 503 | 1278 |

| Iceland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2020 | Iceland Coastal (CIC) | 0 | 217 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2020 | East | 20 | 23 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2020 | West | 162 | 216 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2020 | Total | 182 | 239 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2019 | E | 429 | 1108 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2019 | CM | 0 | 170 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2019 | Total | 429 | 1278 |

| Iceland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2019 | Iceland Coastal (CIC) | 0 | 217 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2019 | East | 11 | 20 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2019 | West | 160 | 164 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2019 | Total | 171 | 184 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2018 | E | 454 | 1108 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2018 | CM | 0 | 170 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2018 | Total | 454 | 1278 |

| Iceland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2018 | Iceland Coastal (CIC) | 6 | 217 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2018 | East | 2 | 15 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2018 | West | 116 | 179 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2018 | Total | 118 | 194 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2017 | E | 432 | 829 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2017 | CM | 0 | 170 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2017 | Total | 432 | 999 |

| Iceland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2017 | Iceland Coastal (CIC) | 17 | 269 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2017 | East | 10 | 15 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2017 | West | 133 | 179 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2017 | Total | 143 | 194 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2016 | E | 591 | 710 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2016 | CM | 0 | 170 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2016 | Total | 591 | 880 |

| Iceland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2016 | Iceland Coastal (CIC) | 46 | 264 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2016 | East | 15 | 15 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2016 | West | 148 | 179 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2016 | Total | 163 | 194 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2015 | E | 660 | 1016 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2015 | CM | 0 | 270 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2015 | Total | 660 | 1286 |

| Iceland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2015 | Iceland Coastal (CIC) | 29 | 275 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2015 | East | 6 | 15 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2015 | West | 133 | 179 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2015 | Total | 139 | 194 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2014 | E | 736 | 1016 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2014 | CM | 0 | 270 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2014 | Total | 736 | 1286 |

| Iceland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2014 | Iceland Coastal (CIC) | 24 | 229 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2014 | East | 11 | 15 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2014 | West | 146 | 164 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2014 | Total | 157 | 179 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2013 | E | 594 | 1016 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2013 | CM | 0 | 270 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2013 | Total | 594 | 1286 |

| Iceland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2013 | Iceland Coastal (CIC) | 35 | 229 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2013 | East | 6 | 12 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2013 | West | 175 | 178 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2013 | Total | 181 | 190 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2012 | E | 464 | 1016 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2012 | CM | 0 | 270 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2012 | Total | 464 | 1286 |

| Iceland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2012 | Iceland Coastal (CIC) | 52 | 229 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2012 | East | 4 | 15 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2012 | West | 148 | 183 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2012 | Total | 152 | 198 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2011 | E | 533 | 1016 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2011 | CM | 0 | 270 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2011 | Total | 533 | 1286 |

| Iceland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2011 | Iceland Coastal (CIC) | 58 | 216 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2011 | East | 10 | 15 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2011 | West | 179 | 185 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2011 | Total | 189 | 200 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2010 | E | 467 | 1016 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2010 | CM | 1 | 270 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2010 | Total | 468 | 1286 |

| Iceland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2010 | Iceland Coastal (CIC) | 60 | 200 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2010 | East | 9 | 15 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2010 | West | 187 | 193 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2010 | Total | 196 | 208 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2009 | E | 485 | 750 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2009 | CM | 0 | 135 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2009 | Total | 485 | 885 |

| Iceland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2009 | Iceland Coastal (CIC) | 81 | 200 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2009 | East | 4 | 15 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2009 | West | 164 | 215 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2009 | Total | 168 | 230 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2008 | E | 506 | 900 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2008 | CM | 30 | 152 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2008 | Total | 536 | 1052 |

| Iceland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2008 | Iceland Coastal (CIC) | 38 | |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2008 | East | 1 | 12 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2008 | West | 151 | 200 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2008 | Total | 152 | 212 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2007 | E | 597 | 900 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2007 | CM | 0 | 152 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2007 | Total | 597 | 1052 |

| Iceland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2007 | Iceland Coastal (CIC) | 43 | |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2007 | East | 2 | 15 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2007 | West | 167 | 169 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2007 | Total | 169 | 184 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2006 | E | 545 | 609 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2006 | CM | 0 | 443 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2006 | Total | 545 | 1052 |

| Iceland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2006 | Iceland Coastal (CIC) | 61 | |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2006 | East | 3 | 14 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2006 | West | 181 | 175 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2006 | Total | 184 | 189 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2005 | E | 634 | 651 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2005 | CM | 5 | 145 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2005 | Total | 639 | 796 |

| Iceland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2005 | Iceland Coastal (CIC) | 39 | |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2005 | East | 4 | 12 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2005 | West | 176 | 176 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2005 | Total | 180 | 188 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2004 | E | 527 | 525 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2004 | CM | 17 | 145 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2004 | Total | 544 | 670 |

| Iceland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2004 | Iceland Coastal (CIC) | 25 | |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2004 | East | 11 | 10 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2004 | West | 179 | 180 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2004 | Total | 190 | 190 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2003 | E | 626 | 674 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2003 | CM | 21 | 37 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2003 | Total | 647 | 711 |

| Iceland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2003 | Iceland Coastal (CIC) | 37 | |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2003 | East | 14 | 12 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2003 | West | 185 | 190 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2003 | Total | 199 | 202 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2002 | E | 599 | 635 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2002 | CM | 35 | 36 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2002 | Total | 634 | 671 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2002 | East | 10 | 10 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2002 | West | 139 | 190 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2002 | Total | 149 | 200 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2001 | E | 521 | 518 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2001 | CM | 31 | 31 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2001 | Total | 552 | 549 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2001 | East | 17 | 12 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2001 | West | 139 | 190 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2001 | Total | 156 | 202 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2000 | E | 430 | 591 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2000 | CM | 57 | 64 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2000 | Total | 487 | 655 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2000 | East | 10 | 10 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2000 | West | 145 | 190 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 2000 | Total | 155 | 200 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 1999 | E | 530 | |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 1999 | CM | 59 | |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 1999 | Total | 589 | 753 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 1999 | East | 15 | 14 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 1999 | West | 170 | 190 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 1999 | Total | 185 | 204 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 1998 | E | 568 | |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 1998 | CM | 57 | |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 1998 | Total | 625 | 671 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 1998 | East | 10 | 12 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 1998 | West | 166 | 190 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 1998 | Total | 176 | 202 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 1997 | E | 482 | |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 1997 | CM | 20 | |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 1997 | Total | 502 | 580 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 1997 | East | 14 | 14 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 1997 | West | 148 | 180 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 1997 | Total | 162 | 194 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 1996 | E | 348 | |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 1996 | CM | 40 | |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 1996 | Total | 388 | 425 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 1996 | East | 12 | 15 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 1996 | West | 164 | 180 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 1996 | Total | 176 | 195 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 1995 | E | 175 | |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 1995 | CM | 42 | |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 1995 | Total | 217 | 232 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 1995 | East | 9 | 15 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 1995 | West | 153 | 180 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 1995 | Total | 162 | 195 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 1994 | E | 237 | |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 1994 | CM | 41 | |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 1994 | Total | 278 | 319 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 1994 | East | 5 | 15 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 1994 | West | 104 | 130 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 1994 | Total | 109 | 145 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 1993 | E | 213 | |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 1993 | CM | 13 | |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 1993 | Total | 226 | 296 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 1993 | E | 0 | 0 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 1993 | CM | 0 | 0 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 1993 | East | 9 | 14 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 1993 | West | 107 | 130 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 1993 | Total | 116 | 144 |

| Norway | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 1992 | Total | 0 | 0 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 1992 | East | 11 | 15 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 1992 | West | 103 | 130 |

| Greenland | Common minke whale | Balaenoptera acutorostrata | 1992 | Total | 114 | 145 |

This database of reported catches is searchable, meaning you can filter the information by for instance country, species, or area. It is also possible to sort it by the different columns, in ascending or descending order, by clicking the column you want to sort by and the associated arrows for the order. By default, 30 entries are shown, but this can be changed in the drop-down menu, where you can decide to show up to 100 entries per page.

Carry-over from previous years is included in the quota numbers, where applicable.

For an explanation and location of the different management areas, have a look under 5. North Atlantic Stocks.

You can find the full catch database with all species here.

For any questions regarding the catch database, please contact the Secretariat at nammco-sec@nammco.no.

Climate Impacts

In some regions, common minke whales appear to be extending their summer range northwards. Recent sightings in Arctic Canada, where they were previously unknown to local residents, suggest this shift (Higdon & Ferguson, 2011). Similarly, there has been an increase in catches by northern communities in West Greenland (NAMMCO, 2012b). These changes are likely responses to shifts in prey distribution, which may be driven by warming marine climates.

For the Central Atlantic stock, significant changes have been observed in oceanographic conditions and the distribution and abundance of several fish species, including sandeels and capelin, and seabirds in Icelandic waters. Recent studies confirm that borealization of the Barents Sea and other northern regions is influencing prey distributions, prompting minke whales to shift their feeding grounds northwards (Haug et al., 2024). These changes in prey distribution are expected to influence the distribution of common minke whales. Additionally, if factors such as ocean currents and water temperature impact migration, feeding, breeding, and calving site selection, changes in these variables could render currently used habitats unsuitable.

Noise

Common minke whales may be affected by noise from human activities such as shipping and resource development, including seismic exploration and drilling. Such noise may interfere with the low frequency sounds the whales use to communicate. Increased noise pollution in Arctic regions, driven by rising vessel traffic, may pose new challenges for minke whales, particularly as they expand their range into previously quieter areas (Sun et al., 2022).

Vessel Strikes

Like fin whales, common minke whales sometimes feed at the surface, making them vulnerable to ship strikes. However, few collisions involving common minke whales have been reported. It is unclear whether this is because they are rarely struck or because, due to their smaller size, collisions go unnoticed by vessels. As vessel traffic increases in Arctic waters, enhanced monitoring and mitigation measures will be essential to minimise the risk of collisions (Haug et al., 2024).

Entanglements

Common minke whales may occasionally be caught as by-catch in fishing nets and other gear, but this is not considered to significantly impact their population in the North Atlantic. Reports of by-catch incidents from the ICES Working Group on By-catch of Protected Species for the period 2008–2012 were very limited (ICES WGBYC, 2011–2014). Nonetheless, ongoing monitoring is critical, especially in regions where changes in fishing practices or gear types might increase entanglement risks (Øien et al., 2024).

Competition with Fisheries

Common minke whales play a significant role as predators in the marine ecosystem, particularly in the Northeast and Central Atlantic stock areas. In the northern Northeast Atlantic stock area, they are estimated to consume over 1.8 million tonnes of prey annually, much of which consists of commercially important fish species such as herring, cod, and haddock (NAMMCO, 1998). This consumption is comparable to the total commercial fishery for pelagic fish in the region (Toresen et al., 1998). Skern-Mauritzen et al (2022) found that marine mammals altogether remove between three and nine times the biomass harvested by fisheries in the northeast Atlantic and that there are large geographical variations of the possible competition between fisheries and marine mammal species.

In Icelandic shelf waters, common minke whales are the most significant marine mammal predators of fish, consuming approximately one million tonnes annually (Sigurjónsson & Vikingsson, 1997). Multispecies modelling suggests that these levels of consumption may have notable implications for the yields of commercial fisheries in the Northeast and Central Atlantic (NAMMCO, 1998; Stefánsson et al., 1997). Recent ecosystem studies underscore the complexity of trophic interactions, highlighting the potential for indirect effects, such as increased capelin stocks, due to minke whale predation on cod (Haug et al., 2024). However, this modelling remains in the early stages.

Minke whale off Iceland. © Marine and Freshwater Research Institute, Iceland.

Research in NAMMCO Member Countries

All NAMMCO member countries, along with Canada, have participated in the NASS and T-NASS surveys, with the common minke whale being a key target species. These surveys are coordinated through the NAMMCO Scientific Committee. In addition to these coordinated efforts, each country conducts independent research into the biology and ecology of common minke whales.

A recent collaborative project, MINTAG, funded by NAMMCO member countries and the Fisheries Agency of Japan, aims to develop advanced satellite tag technology specifically for fast-moving rorquals like minke whales. This project addresses previous challenges in tagging these species, such as minimising tag size, difficulties in attachment and signal transmission, and seeks to enhance understanding of their seasonal migrations and behaviour. The improved tagging technology is expected to provide longer-lasting and more accurate tracking data, which will significantly contribute to minke whale research and conservation efforts

Greenland

Greenland periodically conducts aerial surveys focusing on common minke whales (Hansen et al., 2018; Heide-Jørgensen et al., 2008, 2010). The 2007 survey incorporated still and video cameras alongside human observers, with data analysis using aerial photography and satellite tag information to account for submerged whales during the survey.

In 2018 and 2019, telemetry studies targeting minke whales off Maniitsoq, West Greenland, provided valuable data (National Progress Report Greenland, 2018, 2019).

The Icelandic Minke Whale Research Program. Sampling of blubber thickness © Marine and Freshwater Research Institute, Iceland.

Dr. Heide-Jørgensen, a Greenlandic researcher, has been a leader in developing satellite-linked transmitters and tagging techniques. Tagging common minke whales has proven challenging due to their elusive behaviour, small target size, and tendency to shed tags. The longest recorded tag duration is 101 days, though most last under 30 days, with some failing to transmit (Víkingsson & Heide-Jørgensen, 2013). Research is ongoing, with advancements in tagging methods expected to improve future data collection.

Iceland

The Minke Whale Research Program

After rejoining the IWC in 2003, Iceland initiated a research program focused on minke whales. Conducted under Article VIII of the International Convention on the Regulation of Whaling, which permits scientific research, the program aimed to study feeding ecology, stock structure, distribution, migration, and other biological parameters.

Between 2003 and 2007, 190 minke whales were taken for the program, with more than 70 measurements and 80 samples collected from each whale. The findings, summarised by Pampoulie et al. (2013), were presented at an IWC meeting in 2013.

Diet and feeding studies

Dietary studies revealed that minke whales are opportunistic feeders, predominantly consuming fish. Shifts in diet, such as the reduced importance of sandeels and increased reliance on herring, reflect changes in the marine ecosystem. Stock assessment models, such as Gadget, have been used to explore the relationship between minke whale abundance and prey availability, confirming that whaling mortality is minimal for this stock.

The Icelandic Minke Whale Research Program. Sampling of stomach content. © Marine and Freshwater Research Institute, Iceland.

Other key results of the Program

Determining the age of common minke whales using earplugs or tympanic bullae was found to be unreliable. Instead, ageing through aspartic acid racemisation in the eye lens proved to be more accurate, revealing ages of up to 42 years.

Common minke whales accumulate blubber rapidly during the spring, summer, and autumn feeding seasons. Mature individuals can add up to 500 kg of blubber on feeding grounds, which serves as an energy reserve for growth, reproduction, and migration to and from breeding grounds.

Satellite tagging was attempted on 12 common minke whales, with six tags successfully deployed (Víkingsson & Heide-Jørgensen, 2013, 2014). Of these, three remained active into the whales’ southward autumn migration. These whales were tracked migrating through the mid-Atlantic, with one reaching as far as 28°S before transmissions ceased in early December. During migration, the whales moved significantly faster than those on the Icelandic shelf, averaging over 100 km per day.

Genetics

Genetic analyses have been conducted on a dataset of 737 minke whale samples from Iceland (National Progress Report Iceland, 2020). This research has explored the affinity of Icelandic minke whales with populations in other regions of the North Atlantic. Microsatellite data have been used to infer Parent-Offspring (PO) pairs, providing insights into both regional and ocean-wide movements.