Northern Bottlenose Whale

Updated: July 2020

The northern bottlenose whale (Hyperoodon ampullatus) is a medium-sized toothed whale belonging to the ziphiid, or beaked whale, family. It is found only in the North Atlantic Ocean. These whales are somewhat dolphin-like in appearance, with a beak and falcate (curved) dorsal fin, but they are much larger than most dolphins. The dorsal fin is also smaller and placed further along the back than a dolphin’s. The flippers are small and blunt, and the tail flukes generally do not have a median notch. Northern bottlenose whales have distinctive pronounced foreheads, which are bulbous in females and immature animals but more flat in mature males. The overall body colour ranges from light grey to brown, with a lighter underside. In older adults, the melon and face often become a light grey colour, turning almost white in older males.

ABUNDANCE

In 2017, populations around the UK, Iceland and the Faroe Islands were estimated to number around 19,500 animals. In 2018, an additional 7,800 animals were estimated in the area from the North Sea (southern boundary at 53°N) to the ice edge of the Barents Sea and the Greenland Sea. In 2011, the Scotian Shelf population was estimated to number 164 animals in 2011.

DISTRIBUTION

There are six recognised areas of concentration: four in the North East Atlantic (around Iceland, Svalbard and two locations off mainland Norway), and two in Canadian waters off Nova Scotia and off Labrador and into Davis Strait-southern Baffin Bay.

RELATION TO HUMANS

Northern bottlenose whales are not currently hunted.

CONSERVATION AND MANAGEMENT

NAMMCO provides advice to its member countries on conservation status.

The species is listed as ‘Least concern’ on the regional European IUCN Red List (2023) and on Norwegian national red list (2021). On Icelandic national red list, the species is listed as ‘Data Deficient’.

© Line Anker Kyhn

Scientific name: Hyperoodon ampullatus

Faroese: Døglingur

Greenlandic: Anarnaq

Icelandic: Andarnefja

Norwegian: Nebbhval, andehval, nordlig nebbhval

Danish: Nordlig døgling

English: Northern bottlenose whale, Bottlehead, North Atlantic bottlenose whale

LIFESPAN

The average lifespan of females is around 27 years, while for males it is 37 years.

AVERAGE SIZE

Adults are on average 7-9 m and 5-8 tonnes, but males up to 10 m do occur. Mature males are around 1 m longer than females.

MIGRATION AND MOVEMENTS

There is some degree of variation with indications of migration strategies spanning both small and long distances and some animals not migrating at all.

FEEDING

Northern bottlenose whales appear to occupy a very narrow feeding niche, with their primary prey item being deep-water squid.

General characteristics

The northern bottlenose whale (Hyperoodon ampullatus) is a medium-sized toothed whale belonging to the ziphiid, or beaked whale, family. It is found only in the northern parts of the North Atlantic Ocean. Adult lengths range from 7–9 m on average (DFO 2017). They may reach 10 or 11 m though, with mature males generally being 1 m longer than mature females (COSEWIC 2011). These whales are somewhat dolphin-like in their appearance, with a beak and falcate (curved) dorsal fin. They are, however, much larger than most dolphins. Adult males can weigh from 7–8 tonnes, while adult females can be from 5–6 tonnes (Kovacs & Lydersen 2017). The dorsal fin is also smaller and placed further along the back than a dolphin’s. The flippers are small and blunt, and the tail flukes generally do not have a median notch.

The northern bottlenose whale could be confused with Sowerby’s or Cuvier’s beaked whale, as the ranges of these species overlap in some areas. They can, however, be distinguished by differences in body colouration and by the distinct “melon” (forehead) of the northern bottlenose whale.

© Line Anker Kyhn

Head shape and colouration

Northern bottlenose whales have distinctive pronounced foreheads, which are bulbous in females and immature animals, while more flat and whitish in colour in mature males. Their “beak” carries a single pair of small conical teeth at the tip of the lower jaw, although these have usually only erupted through the gums in older males.

The overall body colour of northern bottlenose whales ranges from light grey to brown, with a lighter underside. Some have suggested that the brown colour results from a film of diatoms on the body (Mead 1989). Calves are grey with dark eye patches and a light-coloured forehead when they are born. Juveniles have a similar appearance, with darker coloured bodies and lighter coloured heads. They also have a more rounded beak and smaller forehead than the adult whales. In older adults, the melon and face often become a light grey colour, turning almost white in older males.

Life History and Ecology

Behaviour

The behaviour of northern bottlenose whales is characterised by two main features: their diving ability and their curiosity.

Diving and surface behaviour

Northern bottlenose whales are among the deepest-diving mammal species in the world, with dives often lasting an hour at depths of more than 1,000 metres. The longest and deepest dive recorded so far for this species was 94 minutes to a depth of 2,340 m (Sivle et al. 2015, Miller et al. 2015). In another study, a tagged individual made regular dives deeper than 800 m (Hooker & Baird 1999). The same study noted two distinct types of dives that the whales made: ‘short duration and shallow’ and ‘long duration and deep’. The short shallow dives generally followed a long deep dive, when the whales remained at or near the surface, sometimes for an hour or more (Whitehead and Hooker 2011).

While at the surface, whales sometimes remain quite still, and at other times may swim quickly in various directions, jump or breach out of the water (Reeves et al. 1993). It has been suggested that the short shallow dives that follow a series of deep dives may serve to reduce tissue and blood supersaturation of nitrogen and so prevent decompression sickness (the “bends”) in these whales (Hooker et al. 2009). The whales may also have certain physiological adaptations to reduce the risk of decompression sickness during their normal diving routine, however, these are unknown at present.

Northern bottlenose whales often socialise at the surface between dives, in groups of 4–20 animals. There is some segregation in the groups by age and sex. Females appear to have looser networks of more short-term relationships, while associations between some males last for several years (Culik 2010, COSEWIC 2011, Whitehead & Hooker 2012). Aggression between males is rare, although they have been observed head butting each other (Gowans et al. 2001).

© Line Anker Kyhn

Curiosity

Northern bottlenose whales appear to be curious. They will approach slow moving or stationary boats and seem to be attracted by unfamiliar noises, such as those made by ship motors or generators. A consequence of this behaviour is that bottlenose whales were easily captured by whalers. Another aspect of their behaviour that often led to their capture is their tendency to remain by wounded companions (Mead 1989, Miller et al. 2015).

Sounds

Northern bottlenose whales make a variety of low-intensity sounds in the human hearing range. They also produce ultrasonic clicks. These clicks are produced when the whales are foraging and are thought to be used for echolocation of their prey. The pattern and frequency range used is distinctive to bottlenose whales (Hooker & Whitehead 2002, Wahlberg et al. 2011).

Life History

The biology of these whales is not well known. Their generally remote and patchy distribution, combined with their lengthy deep diving behaviour, makes them difficult to study. Most of the information known about northern bottlenose whales comes from two main sources: analyses of whales hunted by Norwegian whalers (e.g. Benjaminsen 1972, Christensen 1973, Benjaminsen & Christensen 1979), and studies of living, individually photo-identified whales off the Scotian Shelf of Canada, primarily in a submarine canyon called the Gully (e.g. Gowans et al. 2001, Wimmer & Whitehead 2004).

Males become sexually mature between 7–11 years old, with females maturing slightly later, between 8–12 years old (Benjaminsen & Christensen 1979). Individual life span is estimated to be around 27 years for females and 37 years for males (Christensen 1973, Mead 1989).

The peak time for mating and calving is spring to early summer (Reeves et al. 1993). The main calving period occurs in July–August for whales off the Scotian shelf (Harris et al. 2013). Gestation is thought to be 12 months (Benjaminsen & Christensen 1979, Reeves et al. 1993). Females are thought to give birth every second year, although fewer calves are observed in the Gully population than would be expected if this were the case (Whitehead & Hooker 2011). Of 3,113 sightings between 1988–1999, only 6% were recorded as first-year calves (Whitehead & Hooker 2012). Females in this population may produce a calf every third year. Bottlenose whales in the Baffin Bay – Davis Strait area calve earlier than those off the Scotian shelf, with a peak around April (Whitehead & Hooker 2012).

Food and feeding

Main prey

Northern bottlenose whales appear to occupy a very narrow feeding niche, with their primary prey item being deepwater squid from the genus Gonatus. In the northern parts of their range, the primary species is Gonatus fabricii, whereas in more southerly waters, G. steenstrupi is more commonly eaten. This corresponds to the distribution of these two squid species. In one study examining 2 whales stranded from the North Sea, Gonatus sp. made up more than 99 and 98% of the estimated weight of prey items eaten (Santos et al. 2001). A fatty acid analysis of these prey species found that squid represent a relatively rich food source in terms of their lipid content (Hooker et al. 2001).

Other species of squid are also taken. Stomach contents of 9 whales stranded in the Faroe Islands contained at least 13 different squid species (Bloch et al. 1996), while the stomach contents of whales stranded from the North Sea contained at least 16 different species in one study (Santos et al. 2001) and 21 different species in another (Fernández et al. 2014). Apart from Gonatus, other common taxa found are Teuthowenia spp., Taonius pavo and Histioteuthis reversa (Hooker et al. 2001). For 10 whales stranded from the North Sea, Gonatus spp., Teuthowenia spp. and Taonius pavo together made up more than 90% of the total diet both by weight and number (Fernández et al. 2014).

Other food sources

Fish remains have also been found in the stomachs of northern bottlenose whales, both from stranded animals and those hunted commercially. However, the numbers found have always been low compared to cephalopod prey remains. They have also been found to vary by location: 50% of the whales studied from off Labrador contained fish remains, while only 10% of those off Iceland had eaten any fish (Benjaminsen & Christensen 1979). Fish species found include redfish (Sebastes sp.), Greenland halibut (Reinhardtius hippoglossoides), rabbitfish (Chimaera monstrosa), spiny dogfish (Squalus acanthias), ling (Molva molva) and skate (Raja sp.) (Benjaminsen & Christensen 1979). Northern bottlenose whales occasionally also take other benthic organisms such as sea cucumbers, starfish and prawns (Reeves et al. 1993, Taylor et al. 2008).

Predators

Northern bottlenose whales have few predators apart from humans. Whaling crews have observed killer whales attacking and feeding on them (Harris et al. 2013) and some whales bear scars that are likely from previous attacks.

Distribution and habitat

Northern bottlenose whales are found only in the northern parts of the North Atlantic Ocean. This is a species that occurs in cool and subarctic waters, generally north of about 40°N (COSEWIC 2011). They may travel into broken ice fields, but are more commonly found in open water. On the western side of the Atlantic, they are distributed from Nova Scotia to the Davis Strait, although there have been strandings and sightings as far south as North Carolina in the US (Taylor et al. 2008).

The best-studied subpopulation of these whales is in the waters over “the Gully”–a large submarine canyon off Nova Scotia, Canada (location 44°N, 59°W). The Gully is the southernmost area that northern bottlenose whales consistently occupy in the western Atlantic (Wimmer & Whitehead 2004). In the mid North Atlantic, their range includes both the west and east coasts of Greenland and around Iceland. On the eastern side of the Atlantic, they are found from England north along most of the Norwegian coast and up to the west coast of Svalbard, preferring the deep waters of the Norwegian Sea.

There are no confirmed records from around Novaya Zemlya (Culik 2010) but there have been incidental sightings in the western Barents Sea (Øien & Hartvedt 2011). Northern bottlenose whales have occasionally been seen in both the Mediterranean and Baltic Seas, and have been observed off the Azores and as far south as the Cape Verde Islands (Taylor et al. 2008, Culik 2010, COSEWIC 2011).

Habitat

These whales prefer deep waters, generally from 800–1,800 m deep. They are most abundant in waters more than 1,000 m deep and so are usually found seaward of the continental shelf or in areas of submarine canyons (Reeves et al. 1993, Whitehead & Hooker 2012). Three such canyons (where northern bottlenose whales have been intensively studied), are found on the eastern Scotian Shelf off Nova Scotia, Canada. They are named “the Gully”, Shortland Canyon and Haldimand Canyon. These canyons are thought to be areas where the whale’s main prey (squid of the genus Gonatus) accumulates, but also where the whales socialise, mate and rear their young (DFO 2007). In 2010, these canyons were identified as critical habitat for the population under the Canadian Species at Risk Act (SARA) (DFO 2017).

Northern Bottlenose whale on its side, showing its tail © Line Anker Kyhn

Migrations and movements

It has been suggested that northern bottlenose whales undertake seasonal north-south migrations in some areas, particularly in the Northeastern Atlantic, however the evidence for this is not clear. Norwegian whalers felt that the whales reached their northernmost distribution in the Northeast Atlantic in spring and early summer, and that by July they were moving south (Reeves et al. 1993).

From whaling data, both catch rates and sex ratios varied seasonally in different Northeastern Atlantic locations (Benjaminsen 1972, Benjaminsen & Christensen 1979). This has been interpreted as a result of the whales moving northward in spring and southward in the fall. Strandings on the shores of Europe and Ireland occur most frequently in late summer and autumn, suggesting southward migration at that time (Whitehead & Hooker 2011). One bottlenose whale tagged in the North East Atlantic did appear to migrate, travelling from Jan Mayen Island to the Azores between 22nd June and 4th August 2015 (Miller et al. 2015).

North East Atlantic

In the Norwegian Sea, sightings of bottlenose whales are higher between April and June, but they are sighted there throughout the year (Øien & Hartvedt 2011). Off the Faroe Islands, the whales strand and are caught year round, although in greater numbers in August and September (Bloch et al. 1996). In a feeding study, four whales stranded on European shores in the late summer were found to have been feeding in temperate rather than northern waters prior to stranding, based on the particular prey species found in their stomachs (Fernandez et al. 2014). It is possible that some of the distribution patterns thought to be north–south migrations could instead represent seasonal inshore–offshore movements following particular food resources (Whitehead & Hooker 2012).

North West Atlantic

On the western side of the Atlantic, the Scotian Shelf population does not seem to migrate, as whales are present in the Gully and the other canyons year round (COSEWIC 2011, Whitehead & Hooker 2011). Some movement between canyons is seen, especially by mature males, but some individuals (primarily females) show a preference for particular canyons (Wimmer & Whitehead 2004, Whitehead & Wimmer 2005).

Further north, northern bottlenose whales have been sighted in the Labrador Sea – Baffin Bay area during the winter, which seems to indicate that they too do not migrate seasonally (Reeves et al. 1993, Whitehead & Hooker 2012).

Difference in migration strategies?

It could be that these whales have various migration strategies, even within a single population, with some individuals, age or sex classes migrating large distances, some small distances, and some not at all.

North Atlantic stocks

There are no stocks identified for these whales. However, there are six recognised areas of concentration, based on historic catch distributions. These could potentially represent separate stocks or populations. Four of these are in the North East Atlantic: around Iceland, around Svalbard, and two locations off mainland Norway (one off Andenes and the other off Møre). The other two concentrations are in Canadian waters: along the edge of the Scotian Shelf off Nova Scotia, and off Labrador and into Davis Strait-southern Baffin Bay (COSEWIC 2011, Whitehead & Hooker 2012).

The two Canadian concentrations have been found to be genetically different at both mitochondrial and nuclear markers, indicating that these are two separate populations (Dalebout et al. 2006). Whales in the Gully are also smaller and appear to breed at a different time of year than those found further north (Whitehead et al. 1997, COSEWIC 2011).

Dalebout et al.(2006) compared the genetics of whales from Davis Strait with those sampled from near Iceland and found no genetic differences between these two groups.

Previously, some authors have considered that all the bottlenose whales caught east of Greenland belonged to a single population, with those west of Greenland belonging to a second population. There is, however, no biological evidence for this division. In 1976, the Scientific Committee of the International Whaling Commission (IWC) determined that it would treat northern bottlenose whales as part of one single population (International Whaling Commission 1977).

Current abundance and trends

Estimating the current population size for any of the concentration areas or potential stocks of the northern bottlenose whale is very difficult due to their remote and patchy distribution, and their deep-diving behaviour.

Catch-per-unit-effort methods are also compromised by the whales’ attraction to whaling vessels and their “standing-by” behaviour toward wounded companions.

Population estimates made from visual ship surveys will be negatively biased because of the animals’ long dives, and positively biased because of their attraction to boats (Reeves et al. 1993, NAMMCO 2019). The attraction to vessels is especially hard to correct for, as the degree of attraction may vary with many factors such as location, season, and the type and speed of the survey vessel.

Aerial surveys for these whales only face the deep-diving bias, but the length of time they spend underwater lowers the sighting rate such that not enough data is obtained to be able to make a population estimate.

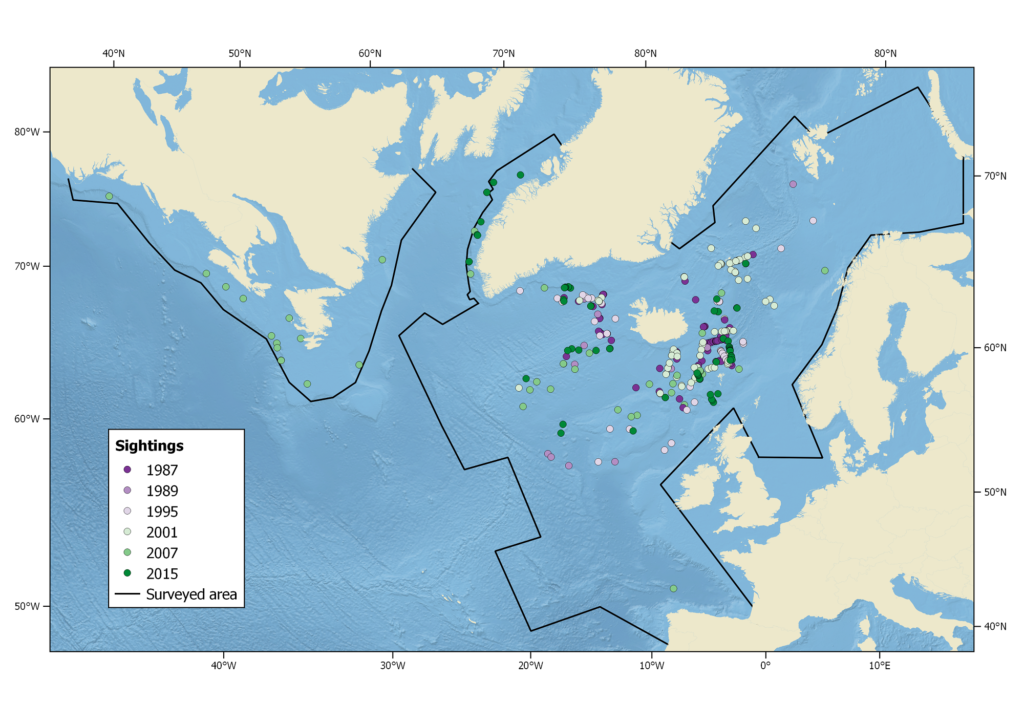

Sightings of northern bottlenose whales in the North Atlantic, showing sightings from all North Atlantic Sightings Surveys (NASS) 1987 – 2015. Not all areas were surveyed in each year.

North East Atlantic

Central

There have been some estimates made of the populations around Iceland and the Faroe Islands. Gunnlaugsson and Sigurjonsson (1990) estimated a population size of 4,925 (CV = 0.16) off Iceland and 902 (CV = 0.45) off the Faroes, based on only 86 sightings made in 1987 and 1989. Later, from a similar survey in 2001, Pike et al. (2003) estimated that there were 27,879 whales (95% CI: 12,396–62,700) around both Iceland and the Faroe Islands based on a ship-based survey conducted in 1995 and 24,561 (95% CI: 15,261–39,528) in 2001 (NAMMCO 2019).

Cañadas et al. (2011, cited in Whitehead & Hooker 2012) made population estimates based on the data from the Faroese 2007 T-NASS ship surveys as well as the 2007 Cetacean Offshore Distribution and Abundance in the European Atlantic (CODA) surveys. They estimated 16,284 (CV = 0.41) northern bottlenose whales in the waters around the Faroes based on 12 sightings and 3,254 (CV = 0.70) in the CODA study area based upon 3 sightings.

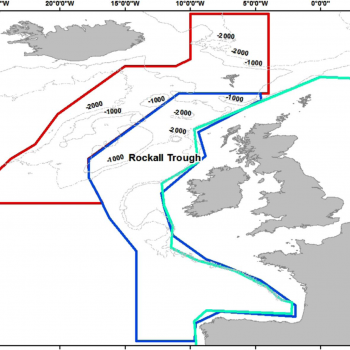

Some of these estimates were revised by Rogan et al. (2017) giving an abundance of 19,539 (95% CI: 9,92–38,482) for the North East Atlantic. The survey areas (outlined in the map to the right taken from Rogan et al. 2017) are: SCANS-II 2005 (cyan), CODA 2007 (blue), and the Faroese block of T-NASS 2007 (red).

On the basis of the 2015 NASS survey, the abundance of bottlenose whales around Iceland and the Faroe Islands was estimated to be 19,975 animals (95% CI: 5,562–71,737) (NAMMCO 2019).

Eastern

In Norwegian and adjacent waters, observations of bottlenose whales have been made during shipboard surveys where the target species is minke whales. Sightings have, however, typically been scarce.

From 1987–2010 a total of 66 primary sightings were made. Bottlenose whales are rarely seen off mainland Norway, but are more common around Svalbard. The most sightings in a single year occurred during the 2005 survey around Jan Mayen Island (13 sightings) and during the 2008 survey in the Svalbard area (13 sightings). In other years, the number of sightings varied from 0–5 (Øien & Hartvedt 2011). There is not enough data to be able to make estimates of either population or density for this area based on these earlier sightings.

In the ship-based survey carried out between 2014-2018, covering the area from the North Sea in the south (southern boundary at 53°N), to the ice edge of the Barents Sea and the Greenland Sea, sufficient sightings were made to generate an abundance estimate. From this survey, an abundance estimate of 7,800 (CV=0.28, 95% CI: 4,373–13,913) was calculated (Leonard & Øien in press).

North West Atlantic

The most-studied population, on the Scotian Shelf off Canada, contains approximately 164 adult and immature whales and appears to be relatively stable, showing no statistically significant trend in the population size between 1988 and 2009 (COSEWIC 2011).

There is no abundance estimate for the Davis Strait-Labrador Sea population of northern bottlenose whales (COSEWIC 2011). Vessel-based and aerial survey efforts between 2003 and 2007 did not yield enough sightings to make a population estimate. The abundance of this population is presumed to be low (Whitehead & Hooker 2011).

Stock status

As discussed in the previous section, it is very difficult to obtain population estimates for this species and so determine with any certainty the past or current status of northern bottlenose whales. Some very rough estimates of the pre-whaling abundance have been made, and it is thought that there were in the order of 100,000 whales in the mid 1800s (Whitehead & Hooker 2012). By 1920, the population had been substantially reduced by fairly intensive whaling. The effects of a second phase of whaling, which took place between 1937 and 1973, are less clear. There is some discussion about whether this second phase led to further depletion of the population, or whether it just slowed any population recovery. This uncertainty is due to the lack of both accurate current population sizes and information on the life history parameters of the species.

Trend?

In the 1970s after whaling had ceased, there were perhaps a few tens of thousands of northern bottlenose whales left. By the mid-1980s, the global population size was thought to be about 54,000, or roughly 60% of the initial stock size (Taylor et al. 2008). While these whales have been unexploited for over 30 years, there is currently not enough information available to state whether or not the overall population is increasing, decreasing or staying stable. The range of these whales does not appear to have changed and they are still found in most areas where whaling occurred, although they are rarely seen now in areas of former concentration off mainland Norway. The signs of possible recovery are, however, better off Svalbard, Iceland and the Faroe Islands where sightings are fairly common.

The population that has been most intensively studied, on the Scotian Shelf off Canada, currently appears to be stable, showing no statistically significant trend in the population size between 1988 and 2009 (COSEWIC 2011).

Based on catch levels, is thought that the Baffin Bay-Davis Strait-Labrador Sea population must have been considerably larger than the Scotian Shelf population prior to the last phase of whaling in 1969. The scarcity of recent sightings could mean that this population remains much reduced, but without more data from properly designed surveys and lacking any current abundance estimates, it can only be concluded that the status of these whales is uncertain (DFO 2007, COSEWIC 2011).

Uncertainty regarding the global status of the northern bottlenose whale led the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) to list this species as “Data deficient” in its 2008 assessment (Taylor et al. 2008).

Management

NAMMCO

The Management Committee of NAMMCO receives advice from the Scientific Committee on the status of the northern bottlenose whales and makes recommendations to member countries based on that advice. The most recent advice with regard to bottlenose whales concerned the Faroe Islands. The Management Committee accepted that the traditional coastal drive hunt in the Faroe Islands did not have any noticeable effect on the population of northern bottlenose whales and that removals of fewer than 300 whales a year were unlikely to lead to a decline (NAMMCO 2015). Current removals in the Faroes are far lower than this and only occur when whales strand themselves and cannot be driven back to sea. There were 5 such strandings in 2014 and 2 in 2015 (NAMMCO 2015).

In Norway, northern bottlenose whales are protected in Svalbard (Kovacs & Lydersen 2017) and there have been no catches of these whales since 1973 (Reeves et al. 1993, Whitehead & Hooker 2012).

COSEWIC

In Canada, the Scotian Shelf population is considered “Endangered” under the Canadian Species at Risk Act (SARA), and the Baffin-Labrador population was listed as of “Special Concern” by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) in May 2011 (COSEWIC 2011). The Gully, a core habitat area for the Scotian shelf population, was designated a Marine Protected Area under the Oceans Act in 2004. This designation prohibits the disturbance, damage, destruction or removal of any living marine organism or habitat within the area (DFO 2017).

Other international organisations

The northern bottlenose whale is listed as a “Protected Species” by the International Whaling Commission, with a catch limit of zero. It is currently listed as “Data deficient” on the IUCN Redlist (Taylor et al. 2008). The species has been listed on Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) since 1984, which means that there is no international trade allowed.

Hunting and utilisation

Historical catches

The northern bottlenose is one of only a few species of beaked whales that has been hunted commercially on a large scale. It was initially hunted for its oil (including a form of spermaceti oil found in the head) and later for its meat, which was used for pet and fur farm food.

Whaling for the northern bottlenose whale was concentrated in six general areas across the northern part of the North Atlantic:

- the Scotian Shelf, Canada

- the Labrador Sea and southern Baffin Bay, Canada

- around Iceland, east Greenland and the Faroe Islands

- Andenes and the Lofoten Islands, off northern mainland Norway

- Møre, off southwestern mainland Norway; and

- Svalbard (Spitzbergen), Norway (Mead, 1989).

In the Faroe Islands, northern bottlenose whales have been taken occasionally in drive hunts or shot offshore for centuries. Catches in this area are very low. Between 1584–1993, 648 bottlenose whales were reported to have been driven ashore in the Faroe Islands and 92 shot offshore (Bloch et al. 1996).

Icelandic stamp

1800s to early 1900s

The main whaling period for this species began in the mid-1800s, as Scottish seal-hunting vessels began to target northern bottlenose whales. From 1877 to 1913, Scottish and British whalers hunted near Cumberland Sound, in Davis Strait, and in the waters off Greenland, and reported approximately 1,669 kills (Reeves et al. 1993; Harris et al. 2013). The British hunt in the Davis Strait-Labrador Sea ended in 1892 (DFO 2007).

The Norwegians began hunting bottlenose whales in the North East Atlantic in the late 1800s. They reportedly took 56,389 whales between 1882 and the late 1920s, primarily east of Greenland, although the early whaling records are not always reliable or available (Whitehead & Hooker 2012).

Whaling records from all areas also do not generally report struck but lost animals, so removal numbers could be higher. Bottlenose whales likely had a significant loss rate as they tend to dive down and sink after being harpooned (ASCOBANS 2017). They were also reported to be “difficult to kill and secure” (Reeves et al. 1993).

Greenlandic stamp

1930s to 1970s

A more recent phase of whaling began in the late 1930s, with the resumption of bottlenose whaling by the Norwegians. A total of 5,836 bottlenose whales were caught during the period 1938–1973, from the main hunting areas off Møre (western Norway), Andenes (northern Norway) and Spitsbergen (Øien & Hartvedt 2011). Later on, bottlenose whaling expanded westwards to the areas between Iceland and Jan Mayen. Between 1969–1971, Norwegian whalers also hunted in the Baffin Bay – Labrador Sea area, taking 818 animals (Reeves et al. 1993; Harris et al. 2013). Norway has not hunted this species since 1973.

A Canadian hunt based out of Blandford, Nova Scotia, took place from 1962–1967. During this period, 87 whales were taken from the Scotian Shelf population (COSEWIC 2011). This population does not seem to have been subject to any hunt prior to that.

Faroese stamp

Commercial whaling of northern bottlenose whales died out everywhere in the early 1970s due to a combination of several factors. The UK banned the import of meat from these whales, Norway found cheaper sources of food for the animals in its fur industry, minke whales became relatively more valuable, and protests against commercial whaling grew.

Recent catches

There is currently no hunt occurring for bottlenose whales. Some may be taken incidentally in the Faroe Islands if they strand and cannot be driven back to sea. In 2015, 2 whales were reported stranded there and in 2014, 5 strandings were reported (NAMMCO, 2015).

Greenland has reported catches of bottlenose whales in the recent past. However, validation of these catches determined that they were actually harbour porpoises that had been incorrectly reported on the catch data form. Bottlenose whales are not normally hunted in Greenland (NAMMCO 2015).

Other human impacts

Some current human impacts on bottlenose whales include by-catch or entanglement in fishing gear, disturbance from oil and gas activities, acoustic disturbance, contaminants, possible changes in food supply, and vessel strikes.

Entanglements

Incidental catch or entanglement of northern bottlenose whales in fishing gear appears to be low. During the past 30 years, only nine entanglements or catches have been reported in Atlantic Canada by DFO. Four of these occurred on the Scotian Shelf, one on the Grand Banks, and three in the Davis Strait area (Harris et al. 2013).

Of the three fisheries implicated in the reported entanglements, only one is still active. The squid and the silver hake fisheries along the edge of the eastern Scotian Shelf ended in the mid 1980s and the late 1990s, respectively, and therefore no longer pose a threat. The swordfish longline fishery, as well as other pelagic longline fisheries, is still conducted in areas of known northern bottlenose whale distribution (DFO 2007).

In the Baffin Bay – Labrador Sea area, photographic and written observer records suggest a greater frequency of interaction with fishing activities than off the Scotian Shelf, at least for a portion of the northern bottlenose whale population. Lawson (2010, in COSEWIC 2011) noted that some whales had scars from fishing lines and some had injuries that could have been caused by propellers or fishing gear.

There have also been other reports from the Davis Strait area. In one case, a fisherman reported a dead northern bottlenose whale caught in a Greenland halibut gillnet. Fisheries observers also reported one whale wrapped in a longline targeting Greenland halibut, which was able to be released alive. Another reported a whale caught by a trawler fishing for Greenland halibut (Harris et al. 2013). Overall, however, the mortality of northern bottlenose whales due to by-catch or entanglement is low.

Noise

© Line Anker Kyhn

Acoustic disturbance is considered a threat of great concern because of the dependence of these and other whales on sound for communication, socialising, foraging, navigation and sensing the environment. Potential sources of underwater noise include military exercises (sonar, detonations), marine scientific research using sound, oil and gas exploration and extraction, vessel traffic, aircraft traffic, and construction.

The loud sounds produced by military sonar have been implicated in fatal stranding events of other beaked whale species (DFO 2007, D’Amico et al. 2009), and represent a concern for bottlenose whales. Over the past few decades, a number of bottlenose whale strandings in the UK appear to be clustered around a submarine testing site in Gairlochhead, near Glasgow (Culik 2010). It is not clear what the direct effects of the sounds are, but the deep-diving behaviour of northern bottlenose whales may make them especially vulnerable to physiological impacts from acoustic disturbance (DFO 2017).

In one field experiment near Jan Mayen Island, northern bottlenose whales were exposed to naval sonar. The whales showed marked behavioural changes when exposed to the noise. The whales stopped foraging, stopped producing foraging sounds, and moved away from the area. The whales’ avoidance of the area started at rather low received sound levels and persisted for several hours after the end of exposure periods (Miller et al. 2015, Sivle et al. 2015).

Effects

Such behavioural changes could have long-term effects on the species if animals that are feeding, resting, or breeding are disturbed by noise. Another effect could be that whales get displaced by noise and forced into areas of poorer habitat.

As discussed in a previous section, northern bottlenose whales have a fairly specialised diet, consisting largely of squid of the genus Gonatus. If whales are displaced by noise or other human activities away from the locations where they find this food, their survival could be compromised. There is currently no human fishery for these squid, but if one were to develop, this too could result in a lack of food for the whales.

Pollutants

Pollutants and the presence of contaminants is a concern for bottlenose whales, as it is for all marine species. Contaminants such as PCBs and organochlorine compounds have been found in bottlenose whale samples, at concentrations similar to other North Atlantic toothed whales (Hooker et al. 2008, DFO 2009). Concentrations of PCBs, DDTs and several other organochlorine compounds were higher in the blubber of whales sampled from the Gully than from the Davis Strait, with significant increases in 4,4′-DDE and trans-nonachlor in 2003 relative to 1996 (Hooker et al. 2008). The contaminant levels found in this study were below those suspected of causing health problems.

Research in NAMMCO member countries

While northern bottlenose whales are not the primary target species, sightings of them are recorded during the NAMMCO-coordinated North Atlantic Sighting Surveys (NASS), as well as in the Norwegian mosaic ship-board surveys. In most cases, there are not enough sightings made to be able to produce a population estimate and this species has a low priority for that work (NAMMCO 2016). There have also been some sightings during recent Greenlandic surveys, but there are no plans to generate an abundance estimate from those (NAMMCO 2016).

In Iceland, a new research project on northern bottlenose whales began in January 2020 by the University of Iceland in collaboration with Marine and Freshwater Research Institute (MFRI) and others. This three-year project will use long-term acoustic monitoring, satellite tags and surface observations to provide new insights into the species’ movement ecology and their vulnerability to high-intensity anthropogenic noise, such as seismic airguns and naval sonar (National Progress Report 2019). Previously, one skin biopsy from a northern bottlenose whale had been obtained in 2013 during a MFRI study on humpback whales.

In the Faroe Islands, biological data was obtained and delivered to the Museum of Natural History from four stranded northern bottlenose whales in 2018 (National Progress Report Faroe Islands 2018).

ASCOBANS. (2017). Agreement on the Conservation of Small Cetaceans in the Baltic, North East Atlantic, Irish and North Seas. Available at http://www.ascobans.org/en/species/hyperoodon-ampullatus

Benjaminsen, T. (1972). On the biology of the bottlenose whale, Hyperoodon ampullatus (Forster). Norwegian Journal of Zoology, 20, 233–241.

Benjaminsen, T. and Christensen, I. (1979). The natural history of the bottlenose whale, Hyperoodon ampullatus (Forster). In H.E. Winn, and B.L. Olla (eds.), Behavior of Marine Animals. Volume 3, 143–164. New York: Plenum. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4684-2985-5_5

Bloch, D., Desportes, G., Zachariassen, M. and Christensen, I. (1996). The northern bottlenose whale in the Faroe Islands, 1584–1993. Journal of Zoology, 239, 123−140. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7998.1996.tb05441.x

Christensen, I. (1973). Age determination, age distribution and growth of bottlenose whales, Hyperoodon ampullatus (Forster), in the Labrador Sea. Norwegian Journal of Zoology, 21, 331–340.

COSEWIC. (2011). COSEWIC assessment and status report on the northern bottlenose whale Hyperoodon ampullatus in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. xii + 31pp.

Culik, B. (2010). Odontocetes. The toothed whales: “Hyperoodon ampullatus“. UNEP/CMS Secretariat, Bonn, Germany. CMS (Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals) 2017. Available at http://www.cms.int/reports/small_cetaceans/data/H_ampullatus/h_ampullatus.htm

Dalebout, M.L., Ruzzante, D.E., Whitehead, H. and Øien, N.I. 2006. Nuclear and mitochondrial markers reveal distinctiveness of a small population of bottlenose whales (Hyperoodon ampullatus) in the western North Atlantic. Molecular Ecology, 15, 3115–3129. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2006.03004.x

D’Amico, A., Gisiner, R.C., Ketten, D.R., Hammock, J.A., Johnson, C., Tyack, P.L. and Mead, J. (2009). Beaked whale strandings and naval exercises. Aquatic Mammals, 35, 452–472. https://doi.org/10.1578/AM.35.4.2009.452

Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO). (2017). Northern Bottlenose Whale (Scotian Shelf population).

Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO). (2009). Contaminant Monitoring in the Gully Marine Protected Area. DFO Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat, Sci. Advis. Rep. 2009/002. Available at http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/csas-sccs/Publications/SAR-AS/2009/2009_002-eng.htm

Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO). (2007). Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada. Recovery potential assessment of northern bottlenose whale, Scotian Shelf population. DFO Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat, Sci. Advis. Rep. 2007/011. Available at https://waves-vagues.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/Library/327975.pdf

Fernández, R., Pierce, G.J., Macleod, C.D. , Brownlow, A., Reid, R.J., Rogan, E., Addink, M., Deaville,R., Jepson, P.D. and Begoña Santos, M. (2014). Strandings of northern bottlenose whales, Hyperoodon ampullatus, in the north-east Atlantic: seasonality and diet. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 94(6), 1109–1116. https://doi.org/10.1017/S002531541300180X

Gowans, S., Whitehead, H. and Hooker, S.K. (2001). Social organization in northern bottlenose whales, Hyperoodon ampullatus: not driven by deep-water foraging? Animal Behaviour, 62, 369–377. https://doi.org/10.1006/anbe.2001.1756

Gunnlaugsson, Th. and Sigurjónsson, J. (1990). NASS-87: Estimation of whale abundance based on observations made onboard Icelandic and Faroese survey vessels. Report of the International Whaling Commission, 40, 571–580.

Harris, L.E., Gross, W.E. and Emery, P.E. (2013). Biology, status, and recovery potential of northern bottlenose whales (Hyperoodon ampullatus). DFO Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat, Res. Doc. 2013/038. v + 35 p. Available at http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/csas-sccs/Publications/SAR-AS/2013/2013_038-eng.html

Hooker, S.K. and Baird, R.W. (1999). Deep-diving behaviour of the northern bottlenose whale, Hyperoodon ampullatus (Cetacea: Ziphiidae). Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B, 266, 671–676. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.1999.0688

Hooker, S.K., Iverson, S.J., Ostrom, P. and Smith, S.C. (2001). Diet of northern bottlenose whales inferred from fatty-acid and stable-isotope analyses of biopsy samples. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 79, 1442–1454. https://doi.org/10.1139/z01-096

Hooker, S.K. and Whitehead, H. (2002). Click characteristics of northern bottlenose whales (Hyperoodon ampullatus). Marine Mammal Science, 18, 69–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-7692.2002.tb01019.x

Hooker, S.K., Baird, R.W. and Fahlman, A. (2009). Could beaked whales get the bends? Effect of diving behaviour and physiology on modelled gas exchange for three species: Ziphius cavirostris, Mesoplodon densirostris and Hyperoodon ampullatus. Respiratory Physiology & Neurobiology, 167, 235–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resp.2009.04.023

Hooker, S.K., Metcalfe, T.L., Metcalfe, C.D., Angell, C.M., Wilson, J.Y., Moore, M.J. and Whitehead, H. (2008). Changes in persistent contaminant concentration and CYP1A1 protein expression in biopsy samples from northern bottlenose whales, Hyperoodon ampullatus, following onset of nearby oil and gas development. Environmental Pollution, 152, 205–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2007.05.027

International Whaling Commission (IWC). (1977). Report of the working group on North Atlantic whales. Oslo, April 1976. Report of the International Whaling Commission, 27, 369−387.

Kovacs, K.M. and Lydersen, C. (2017). Northern bottlenose whale. Norwegian Polar Institute. Available at http://www.npolar.no/en/species/northern-bottlenose-whale.html

Mead, J.G. (1989). Bottlenose Whales – Hyperoodon ampullatus (Forster, 1770) and Hyperoodon planifrons (Fowler, 1882). In S.H. Ridgway and S.R. Harrison (eds.), Handbook of marine mammals. Volume 4: River dolphins and the larger toothed whales, 321–348. London, UK: Academic Press.

Miller, P.J.O., Kvadsheim, P.H., Lam, F.P.A., Tyack, P.L., Curé, C., DeRuiter, S.L., Kleivane, L., Sivle, L.D.,van IJsselmuide,S.P., Visser, F.,Wensveen,P.J., von Benda-Beckmann,A.M., Martín López, L.M., Narazaki, T. and Hooker, S.K. (2015). First indications that northern bottlenose whales are sensitive to behavioural disturbance from anthropogenic noise. Royal Society Open Science, 2(6), 140484. http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rsos.140484

North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO). (2015). Annual report 2015. NAMMCO, Tromsø, Norway. 374 p. Available at https://nammco.no/topics/annual-reports/

North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO). (2016). Report of the 23rd Scientific Committee Meeting, Nuuk, Greenland. NAMMCO, Tromsø, Norway. Available at https://nammco.no/topics/scientific-committee-reports/

North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO). (2019). Report of the Abundance Estimates Working Group, October 2019. Tromsø, Norway. Available at https://nammco.no/topics/abundance_estimates_reports/

Øien, N. and Hartvedt, S. (2011) Northern bottlenose whales Hyperoodon ampullatus in Norwegian and adjacent waters. Paper presented to the IWC Scientific Committee, May 2011 SC/63/SM1. Cambridge: IWC.

Pike, D.G., Gunnlaugsson, T., Víkingsson, G.A., Desportes, G. and Mikkelson, B. (2003). Surface abundance of northern bottlenose whales (Hyperoodon ampulatus) from NASS-1995 and 2001 shipboard surveys. NAMMCO/SC/11/AE/11, Tromsø.

Reeves, R.R., Mitchell, E. and Whitehead, H. (1993). Status of the northern bottlenose whale, Hyperoodon ampullatus. Canadian Field-Naturalist, 107, 490–508.

Rogan, E., Canadas, A., Macleod, K., Santos, B., Mikkelsen, B., Uriarte, A., Van Canneyt, O., Vazquez, J.A. and Hammond, P.S. (2017). Distribution, abundance and habitat use of deep diving cetaceans in the North East Atlantic. Deep–Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 141, 8–19. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr2.2017.03.015

Santos, M.B., Pierce, G.J., Smeenk, C., Addink, M.J., Kinze, C.C., Tourgaard, S. and Herman, J. (2001). Stomach contents of northern bottlenose whales Hyperoodon ampullatus stranded in the North Sea. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 81, 143–150. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025315401003484

Sivle, L.D., Kvadsheim, P.H., Curé, C., Isojunno, S., Wensveen, P.J., Lam,F-P. A., Visser, F., Kleivane, L., Tyack, P.L., Harris, C.M. and Miller, P.J.O. (2015). Severity of expert-identified behavioural responses of humpback whale, minke whale, and northern bottlenose whale to naval sonar. Aquatic Mammals, 41(4), 469–502. https://doi.org/10.1578/AM.41.4.2015.469

Taylor, B.L., Baird, R., Barlow, J., Dawson, S.M., Ford, J., Mead, J.G., Notarbartolo di Sciara, G., Wade, P. and Pitman, R.L. (2008). Hyperoodon ampullatus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2008: e.T10707A3208523. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T10707A3208523.en.

Wahlberg, M., Beedholm, K., Heerfordt, A. and Møhl, B. (2011). Characteristics of biosonar signals from the northern bottlenose whale, Hyperoodon ampullatus. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 130(5), 3077–3084. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.3641434

Whitehead, H. and Hooker, S.K. (2012). Uncertain status of the northern bottlenose whale Hyperoodon ampullatus: population fragmentation, legacy of whaling and current threats. Endangered Species Research, 19, 47–61. https://doi.org/10.3354/esr00458

Whitehead, H. and Hooker, S.K. (2011). Status of northern bottlenose whales. International Whaling Commission Scientific Committee. SC/63/SM4

Whitehead, H. and Wimmer, T. (2005). Heterogeneity and the mark-recapture assessment of the Scotian Shelf population of northern bottlenose whales (Hyperoodon ampullatus). Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 62, 2573–2585. https://doi.org/10.1139/f05-178

Weir, C.R. 2023. Hyperoodon ampullatus (Europe assessment). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2023: e.T10707A221058609. Accessed on 22 December 2023.

Whitehead, H., Gowans, S., Faucher, A. and McCarrey, S.W. (1997). Population analysis of northern bottlenose whales in the Gully, Nova Scotia. Marine Mammal Science, 13, 173–185. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-7692.1997.tb00625.x

Wimmer, T. and Whitehead, H. (2004). Movements and distribution of northern bottlenose whales, Hyperoodon ampullatus, on the Scotian Slope and in adjacent waters. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 82, 1782–1794. https://doi.org/10.1139/z04-168

Norwegian Polar Institute – Northern bottlenose whale

Sea Watch Foundation – Northern bottlenose whale in UK waters

Voices in the Sea – The northern bottlenose whale (includes a sound recording)

Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society – Northern bottlenose whale

Canadian Department of Fisheries and Oceans – Northern bottlenose whale

International Union for the Conservation of Nature, “Red List”