Bearded Seal

Updated: June 2025

The bearded seal gets its name from the long whiskers on its muzzle. Another English name for them, “square flipper”, refers to their large pectoral flippers which are flattened at the ends. These characteristics, plus the fact that the head appears small relative to the overall body size, make the bearded seal easy to distinguish from other northern seals.

Bearded seals are found throughout the Arctic and are the largest species of seal in the north being able to reach lengths of 2.1–2.7 m in length and weigh between 200–430 kg (DFO 2016). Males and females are difficult to distinguish, although in the spring the females tend to be slightly larger than the males. The largest bearded seal recorded was a female that weighed 432 kg (Cameron et al., 2010) and maximum body size is reached when the seal is 9–10 years old. Bearded seals may live for up to 30 years.

Abundance

Estimates suggest that there are approximately 500,000 to 1 million bearded seals across the Arctic, however the data available is rather poor.

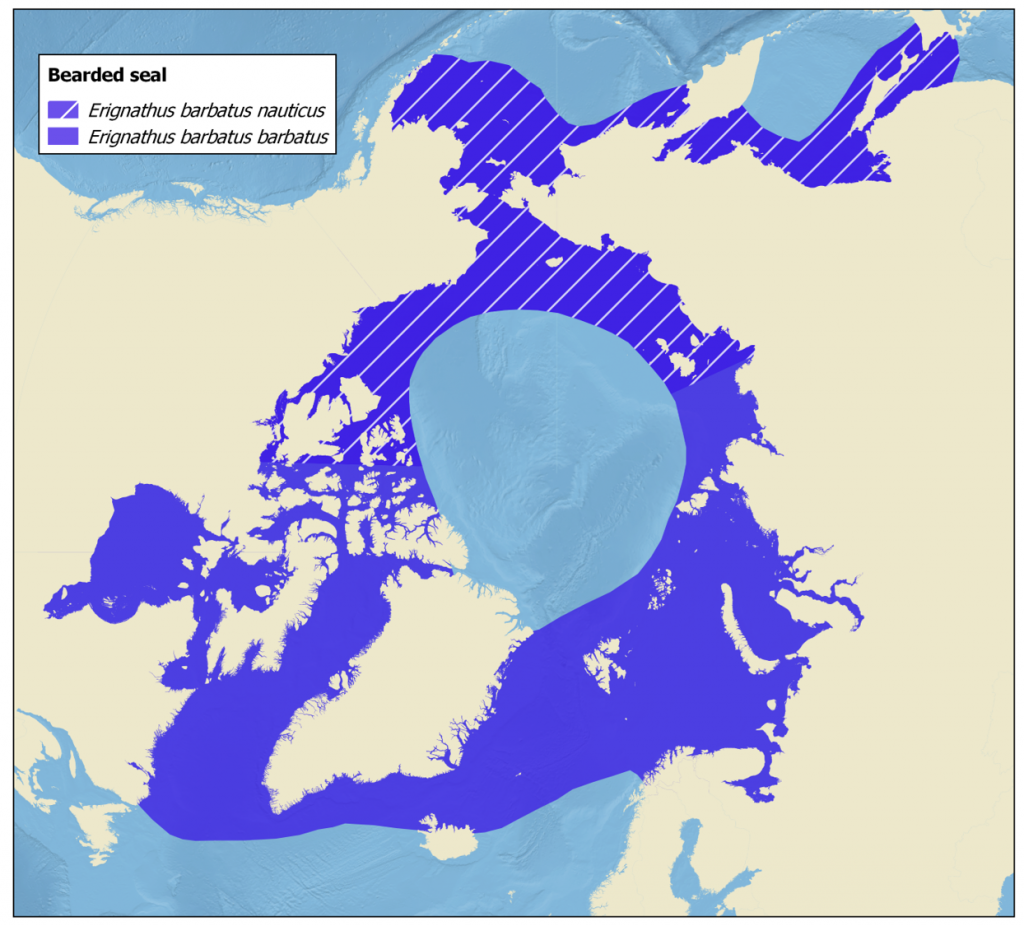

Distribution

They are found throughout the Arctic and sub-Arctic and are strongly associated with sea ice.

Relation to Humans

There is a subsistence hunt of bearded seals throughout their range, with some previous commercial hunt in Svalbard and Russia. There is also currently a small sport-hunt in Svalbard.

Conservation and Management

NAMMCO provides management advice on bearded seals to its member countries. In both Greenland and mainland Norway, hunters must have a permit to hunt bearded seals, but there is no quota system in place. In Svalbard, however, hunting is only allowed in a very restricted area and is tightly regulated.

The most recent assessment (2016) listed the species as ‘Least Concern’ on the global IUCN Red List. However, in Norway, the species is listed as Near Threatened on the 2021Norwegian national Red List, due to concerns over climate change and the associated loss of sea ice habitat.

Bearded seal © Martha de Jong Lantink

Scientific name: Erignathus barbatus (Erxleben 1777)

Erignathus barbatus barbatus – “Atlantic” subspecies

Erignathus barbatus nauticus – “Pacific” subspecies

Faroese: Granarkópur

Greenlandic: Ussuk

Icelandic: Kampselur, Granselur, Kampur

Norwegian: Storkobbe

Danish: Remmesæl

English: Bearded seal, Square flipper

Lifespan

Bearded seals live to around 30 years old.

Average Size

They are typically 2.1-2.7 m in length and 200-430 kg in weight.

Migration and Movements

Bearded seals stay around the ice edge, following it as it moves seasonally.

Feeding

They are benthic (bottom) feeders, eating mostly fish but also some invertebrates.

General characteristics

© Danita Delimont/Shutterstock.com

Adult bearded seals have dark grey or brown fur, often with reddish-brown colouring on the face and pectoral flippers. This reddish hue is especially common in individuals from Svalbard and is thought to result from feeding on bottom-dwelling organisms that live in iron-rich sediments (Lydersen et al., 2001). Juveniles are generally lighter grey or brown, with paler faces.

Pups are born with a layer of blubber and are capable of swimming and diving from the first day of life (Lydersen et al., 1994; Lydersen et al., 1996). Contrary to earlier belief, they are not born with a lanugo coat. Instead, the lanugo is shed while still in the womb and expelled at birth along with the placenta in the form of discs (Kovacs et al. 1996).

Recent research has provided an updated understanding of bearded seal subspecies. Genetic and evolutionary evidence now supports the existence of three distinct genetic groups rather than the previously assumed two subspecies. These groups are associated with the Atlantic Arctic, the Pacific Arctic, and the Sea of Okhotsk, with overlapping ranges and no clear geographical boundaries (McCarthy et al., 2025). These findings revise earlier conclusions based on genetic and vocalisation differences (e.g. Davis et al., 2008; Charrier et al., 2013; Risch et al., 2007) and reflect a more complex and nuanced view of population structure shaped by past and present icescapes.

Behaviour

Social behaviour

Bearded seals are generally solitary animals and are typically observed alone or in small groups across their range. However, during the breeding season, males become more social and vocal. They produce complex underwater vocalisations to advertise their breeding condition and possibly to defend territories (Mizuguchi et al., 2016; Charrier et al., 2013). Earlier studies from Svalbard provided detailed insights into these behaviours, showing that vocalising males are most active between early April and mid-July, when female presence in the water is highest (Van Parijs et al., 2001).

Males often position themselves at strategic locations, such as fjord entrances, where they are more likely to encounter receptive females (Van Parijs et al., 2001). Research has also shown that males may employ different mating tactics, such as remaining stationary or moving between calling sites, possibly to increase their chances of attracting mates (Van Parijs et al., 2003). Furthermore, sea ice conditions can influence male behaviour, with changes in ice cover affecting both their calling activity and movement patterns (Van Parijs et al., 2004).

During the breeding season, males may also become aggressive towards one another, displaying both bubble-blowing behaviours and engaging in direct physical contact (Kovacs, 2016).

© Ondrej Prosicky/Shutterstock.com

Habitat preference

Bearded seals maintain a close association with sea ice throughout their lives, particularly during critical life history periods concerning reproduction and moulting. They show a preference for areas of moving pack ice and open water, such as leads and polynyas, where the water depth is generally less than 200 m. Nevertheless, researchers have observed bearded seals creating breathing holes in landfast ice and inhabiting deeper areas. In the open water season, these seals are entering river estuaries and hauling out on land (Stewart & Lockhart, 2005). Although their primary habitat is coastal regions, they can also be found in drifting pack ice situated far from the shore in shallow (and also deep water) areas such as the Bering and Barents Seas (Kovacs et al., 2011).

Bearded seals overwinter near polynyas or other areas with leads, drifting ice and open water, or they stay near ice edges. The “North Water”, a large annual polynya between Canada and Greenland, is an important overwintering location for bearded seals. An aerial survey conducted over the eastern part of the North Water in April 2014 found an estimated 10,000 bearded seals there (NAMMCO, 2015).

In some areas, as in the Bering and Chukchi seas, they undergo seasonal movements with the advance and retreat of sea ice (Kovacs, 2016). In other parts of their range, they stay more or less in the same area year-round, making more local movements in response to ice conditions (Hamilton et al, 2018).

Sexual maturity and breeding

In general, bearded seals attain sexual maturity at 5‐6 years old for females and 6‐7 for males (Cameron et al., 2010). In Svalbard, studies show that females become sexually mature at around 5 years of age (Kovacs, 2016). Although males become mature at around the same age as females, they may not successfully breed until they are older.

The majority of mature females breed each year and produce one pup. Variation in pregnancy rates has however been recorded for various locations (Cameron et al., 2010). These variations may indicate differences in carrying capacity between the various habitats.

As in other phocid (earless) seals, the mother ovulates towards the end of the nursing period and mates after the she weaned her pup (Kovacs, 2016). Similar to other seals, bearded seals undergo embryonic diapause with implantation occurring in late July or early August.

Two bearded seals on ice © Sergey Uryadnikov/Shutterstock.com

Pups

Bearded seal pups are born on sea ice, either on pack ice or small floes of annual sea ice (Kovacs et al., 1996). In Svalbard, females have also been observed using loose pieces of glacier ice for birthing and nursing when sea ice is not available (Lydersen et al., 2014). Pupping occurs from late March to mid-May across most of the species’ range, with peak pupping in Svalbard taking place in early May.

Bearded seal pups are large at birth, measuring about 130 cm in length and weighing between 34 and 40 kg (Kovacs et al., 1996). They are not born with a lanugo coat, as it is shed in the womb and expelled at birth with the placenta (Kovacs et al., 1996). The nursing period lasts 18–24 days, during which pups gain weight rapidly, around 3.3 kg per day (Lydersen et al., 1996). By the time of weaning, they often weigh over 100 kg (Gjertz et al., 2000; Lydersen & Kovacs, 1999).

Pup behaviour

Bearded seal pups are capable of swimming and following the adult female soon after birth (Hammill et al., 1994). A study of four nursing pups found that they spent about 53% of the time in the water and were submerged for 42% of that time (Lydersen et al., 1994). Six of the seven pups tagged in a study at Svalbard dived deeper than 448 m by the time they were 2 months old (Gjertz et al., 2000). This early swimming ability may have evolved so that the young can escape predation by polar bears, the bearded seal’s main predator. There is also evidence that pups are learning to catch and feed on small prey while they are still nursing (Lydersen et al., 1996).

Nursing females spend over 80% of their time in the water while caring for a dependent pup and only haul-out to nurse three times a day on average (Lydersen & Kovacs, 1999). This might be a response to polar bear predation, as that a pup alone on the ice is less conspicuous than both a pup and mother.

Vocalisations

Bearded seal vocalising © Sergey Uryadnikov/Shutterstock.com

during the breeding season. In the Beaufort Sea, they have been heard calling year-round, with increased activity as pack ice forms in winter, peaking in spring during mating (MacIntyre et al., 2013). Males begin developing vocal displays around the onset of sexual maturity. These displays are key for attracting mates and competing with other males. Captive studies show that young or inexperienced males produce shorter and simpler calls compared to adult males in the wild (Davies et al., 2006). The most common calls, known as “trills”, can be heard from as far as 25 to 45 km away in calm conditions (Jones et al., 2014).

Individual males have distinctive vocalisations. Research from Svalbard showed that these vocal differences serve both to advertise breeding condition and to defend territories (Van Parijs et al., 2001; 2003). Male bearded seals show alternative mating tactics. Some return to the same display sites year after year and defend them aggressively, while others roam over larger areas and do not defend specific sites. These tactics are influenced by environmental factors such as ice conditions (Van Parijs et al., 2004; Van Parijs & Clark, 2006).

The type and timing of vocalisations vary by location and strategy. In Svalbard, territorial males produced longer calls than roaming ones, whereas the opposite pattern was found in Alaska (Van Parijs & Clark, 2006). Recent studies have also shown that the use of specific trill types differs by site and season. For example, long trills were used most frequently in a drift-ice area north of Svalbard, while a land-fast ice site showed more balanced use of different trill types. In contrast, little variation in trill type was observed in Kongsfjorden, where ice cover has declined significantly (Llobet et al., 2021). These differences likely reflect adaptations to local environmental conditions and breeding strategies.

Males are aggressive towards each other during the breeding season, with displays of bubble-blowing and physical combat, indicating that the mating system is likely polygynous (Kovacs, 2016). Mating occurs in the water, making it difficult to observe directly.

Moulting usually takes place after mating, between March and May depending on the location, though it can occur as late as August (Kovacs, 2016). During the moult, bearded seals are often thought to spend more time hauled out, but telemetry data from adult seals in Svalbard suggest that some individuals may haul out for as little as 5% of their total time during this period (Hamilton et al., 2018). This shows that haul-out behaviour during moult may vary more than previously assumed.

Food and Feeding

Bearded seals are primarily benthic (bottom) feeders, but their diet varies by age, location and season. They have been characterised as a “foraging generalist” able to prey on a wide variety of items throughout their circumpolar range (Antonelis et al., 1994). See Cameron et al., (2010) for a full list of prey items.

Major food items

Fish constitute a major portion of the diet. In 15 of 19 bearded seals from the Canadian high Arctic, whose stomachs contained more than 1 kg food, fish made up over 90% of the wet weight (Finlay & Evans 1983). Twelve different species of fish were present in those stomachs, with sculpins (Cottidae) and arctic cod (Boreogadus saida) the most common. A study of the stomach contents of 78 bearded seals in the Bering Sea found that 86% of the stomachs contained fish, including capelin (82%) and gadoids (64%) (Antonelis et al., 1994). In one study from Svalbard, fish accounted for 70% of the diet, with arctic cod, sculpins, and long rough dab (Hippoglossoides platessoides) being the most common species (Hjelset et al., 1999).

Capelin

Other benthic invertebrates are important in the diet. Bearded seals can capture prey on the bottom or use their broad muscular snouts to extract prey from the substrate by powerful suction and water-jetting (Marshall et al., 2016). Their long mystacial vibrissae (whiskers) aid them in locating and identifying buried prey. The main invertebrate prey taken are benthic polychaetes, crustaceans and molluscs.

The whelk Buccinum and the shrimp Sclerocrangon boreas accounted for most of the invertebrate component of the diet in the Canadian High Arctic. Clams, cephalopods, anemones, sea cucumbers, polychaete worms and other invertebrates occurred in small amounts (Finlay & Evans 1983).

Variations

Bearded seal diets have demonstrated to change with changing ice conditions. In Svalbard, seal diets consisted of more pelagic fish species and fewer benthic invertebrates in the years with the most extensive fast ice, while the opposite was seen in the years when the fjords were relatively ice free (Hindell et al., 2012).

In the central Bering Sea, Antonelis et al., (1994) detected no differences between the diets of males and females or between adults and juveniles, indicating no apparent change in the diet or feeding habits according to sex or age.

Predators

Polar bears are the main predators of bearded seals, although walruses, killer whales and Greenland sharks occasionally hunt them as well (Kovacs, 2016; Cameron et al., 2010; Cleator, 1996). Walruses appear to primarily take young seals (Cleator, 1996).

Adult polar bear feeding on the remains of a bearded seal kill, Svalbard Archipelago, Norwegian Arctic © Nora Yusuf/Shutterstock.com

Health and parasites

Bearded seals host a wide variety of parasites across their circumpolar range. Parasitic worms are common, including cestodes, trematodes, nematodes and acanthocephalans. These helminths most often infect the stomach and intestinal tract but have also been found in the heart, lungs and gall bladder. A complete list of parasite species is available in Cameron et al. (2010). The nematode Trichinella has been detected in bearded seals (Forbes, 2000), which is relevant for human health as it can cause trichinosis if infected meat is consumed raw or undercooked.

Protozoan parasites can also occur. In one small study, Giardia duodenalis was found in three out of four bearded seals sampled in Nunavik, Quebec, while Cryptosporidium spp. were not detected (Dixon et al., 2008). These protozoa can cause gastrointestinal illness in humans.

Knowledge about viral and bacterial diseases in bearded seals remains limited. However, Brucella pinnipedialis has been isolated from this species. Antibodies were detected in 19% of tested seals from the Chukchi Sea and 8% from Svalbard (Foster et al., 2018), indicating exposure in some populations. Barratclough et al. (2023) further highlight Brucella as a pathogen of concern, though clinical symptoms and population-level impacts in bearded seals are not well understood. This review also points out the importance of monitoring for emerging zoonotic diseases and mentions that bearded seals may be susceptible to pathogens such as influenza A viruses and morbilliviruses, although confirmed cases remain rare. Overall, disease surveillance in this species is still sparse, and further research is needed to assess health risks, particularly under changing environmental conditions.

Stock distribution, habitat and migrations

Bearded seals have a circumpolar distribution throughout much of the Arctic and sub-Arctic, generally occurring south of 85°N. Their presence is closely linked to sea ice, which is essential for critical life history activities such as pupping, nursing and moulting, as well as to areas of high benthic productivity for feeding. They are typically seen alone or in small groups and tend to occur in patchy, low-density distributions. Currently, distinct management stocks are not formally recognised.

In regions such as the Bering and Chukchi Seas, bearded seals undertake seasonal migrations, following the advance and retreat of sea ice (Kovacs, 2016). In other areas, such as parts of the Canadian Arctic and Svalbard, individuals may remain in the same general region throughout the year.

Bearded seals show a preference for areas with drifting pack ice and access to open water, often in shallow continental shelf regions with depths less than 200 metres. However, they are also known to maintain breathing holes in landfast ice and occasionally use deeper offshore areas. During the open-water season, they may enter estuaries and rivers, and in some areas haul out on land (Stewart & Lockhart, 2005).

The North Atlantic

In the North Atlantic, bearded seals are found in Hudson Bay and much of the eastern Canadian Arctic Archipelago, extending south to southern Labrador, and along both coasts of Greenland. They are also present in the Barents Sea, the Svalbard Archipelago, the north coast of Iceland, and across northern Russia as far east as the Laptev Sea (Kovacs, 2016). While not native to Iceland, bearded seals occasionally appear along the northern and northwestern coasts (Hauksson & Bogason, 1995).

Sightings far outside their usual range have been recorded. On the European side of the Atlantic, individual seals have been reported as far south as Portugal. On the western side, a bearded seal was observed in the harbour at Gloucester, Massachusetts (Sardi & Merigo, 2006). Such occurrences are rare and likely involve dispersing individuals rather than established populations.

North Atlantic Stocks

Biologists use the term stock to describe a subpopulation of a species that is largely reproductively isolated from others of the same species. Due to this isolation, stocks can often be distinguished by genetic differences if they have been separated for long enough. Other ways to differentiate stocks include morphometrics (body size and shape), pollutant or trace element profiles in tissues, behaviour (such as vocal dialects), and movement patterns. From a management perspective, the key feature of a stock is that harvesting or depleting one stock should have minimal or no impact on neighbouring stocks.

Note the square front flippers characteristic of bearded seals© Smudge 9000

Bearded seals occur throughout the Arctic in a patchy, low-density distribution. While distinct stocks or breeding populations may exist, current knowledge is insufficient to clearly delineate them, and no formal stock structure is currently recognised for management purposes.

Historically, two subspecies of bearded seals have been recognised: Erignathus barbatus barbatus (Atlantic) and E. b. nauticus (Pacific). The Atlantic form ranges from the central Canadian Arctic eastward to the central Eurasian Arctic, while the Pacific form is found from the Laptev Sea eastward, including the Sea of Okhotsk, into the central Canadian Arctic. Although the boundary between these groups remains uncertain, support for recognising two subspecies has come from earlier genetic studies (Davis et al., 2008) and differences in vocalisations (Charrier et al., 2013; Risch et al., 2007).

However, recent research by McCarthy et al., 2025 has revealed a more complex population structure than previously understood. Their large-scale genomic study identified at least three genetically distinct clusters of bearded seals associated with:

- The Atlantic Arctic (including Canada, Greenland, and Svalbard)

- The Pacific Arctic (including the Chukchi and Bering Seas)

- The Sea of Okhotsk

These findings challenge the traditional two-subspecies view and suggest that bearded seals have a more dynamic evolutionary history shaped by past and present icescape connectivity. The study also highlights gene flow across regions and suggests that ice conditions may act as both barriers and corridors for movement, depending on the time period. These results have important implications for understanding bearded seal ecology and for designing conservation and management strategies.

Current abundance and trends

Current population numbers and trends for bearded seals are not well known. There are several factors that make it difficult to accurately assess bearded seal populations. Firstly, their remote and broad distribution makes surveying them expensive and logistically challenging. As a result, population surveys for these and some other Arctic marine mammals are “infrequent, incomplete or simply non-existent” (Kovacs et al., 2011). Furthermore, the range of the species spans several political boundaries and since there has not been much international cooperation to conduct range‐wide surveys, estimating current abundance is difficult.

Estimates of the total world population of bearded seals have ranged from 500,000 to around 1 million (Cameron et al., 2010). Laidre et al., (2015) summarised known population data for bearded seals throughout their range but described the data available as “poor and outdated”. The methods used to arrive at bearded seal population numbers have varied with time and location, making comparison of the numbers difficult. Because of this, there are no reliable quantitative estimates of population trends for the species.

For most of the range of the Atlantic subspecies (E.b. barbatus) no population numbers or trends are known (Laidre et al., 2015). Cleator (1996) suggested a minimum population of 190,000 bearded seals for Canadian waters, but this number was based on summing different indices made between 1958 and 1979, rather than any direct population survey. The Greenland Institute of Natural Resources estimates that there are approximately 250,000 of the E.b. barbatus subspecies (GINR 2016).

Stock status

Bearded seals occur throughout the Arctic in a patchy, low-density distribution. There may be distinct stocks or breeding populations, however, not enough is known at this time in order to be able to delineate them and therefore none are currently recognised.

There is subsistence hunt of bearded seals throughout their range, although this is at low levels relative to other seal species. Catch rates for bearded seals in all countries are considered small relative to the local populations and hunting is believed to have little impact on abundance (Cameron et al., 2010). There is a general belief that the bearded seals’ distribution at relatively low densities across a vast area contributes to their protection from overexploitation (GINR, 2016).

© NOAA

Management

There is no international governing body that regulates the hunting of bearded seals. Advice on the management of bearded seals can be provided by the North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO). If requested by a member country, the NAMMCO Scientific Committee will prepare advice on the size of a sustainable hunt based on existing data, which the Management Committee will then consider when it proposes measures for conservation and management to member countries.

Greenland

In Greenland, Government of Greenland regulates the management of marine mammals and local municipalities carry it out by putting in place by-laws restricting hunting by area, season, or hunting method. All hunters must have a permit and provide catch records.

Bearded seals may be hunted year-round and there are no Total Allowable Catches (TACs) or allocations set. There are some restrictions on the hunting of seals in Melville Bay Nature Reserve and in the national park in North and East Greenland (Cameron et al., 2010).

Management advice is provided to the Greenland Government through NAMMCO.

Norway

Bearded seals do not usually occur along the mainland coast and the Norwegian Marine Resources Act sets no quotas for the hunting of this species. The Svalbard Environmental Protection Act manages the hunt of bearded seals in Svalbard waters (Cameron et al., 2010).

Licensed hunters can shoot bearded seals in Svalbard during a restricted season, in a restricted area. There is no TAC for Svalbard and only a small number of seals are taken each year.

Canada

The federal Department of Fisheries and Oceans and regional resource management boards, such as the Nunavut Wildlife Management Board, co-manage bearded seals in Canada. The 2011-2015 Integrated Fisheries Management Plan for Atlantic Seals (DFO 2016) includes provisions for bearded seals, although no Total Allowable Catches (TACs) or allocations have been set at present. If there was to be any commercial catch, licences and permits would be required. However, the catch of bearded seals for subsistence purposes is permitted year-round (DFO, 2016).

Russia

In Russia, the “Law of Fisheries and Preservation of Aquatic Resources” provides for subsistence hunt of seals by aboriginal Russian peoples and a TAC for the commercial catch is determined annually by the Russian Federal Fisheries Agency. Russia is the only nation to set a quota on the number of bearded seals that can be hunted (Kovacs, 2016).

Recent Catches

There is currently a legal subsistence catch of bearded seals throughout their range (Laidre et al., 2015). Bearded seals have a tough, flexible hide which is valued for many purposes, such as lines or rope, kayak coverings, and kamik (boot) soles while the meat is also suitable for human and dog food (Hovelsrud et al., 2008).

Greenland

In Greenland, hunting of bearded seals takes place throughout the year. During the winter in North Greenland, they are hunted by their breathing holes in the ice and by netting close to shore. In spring they are hunted while basking on the sea ice and in summer they are hunted in open water from boats (Hovelsrud et al., 2008).

From 2005 to 2007, between 1454 and 1773 bearded seals were taken in Greenland (NAMMCO, 2009). More recently (2011 to 2013), catches have dropped slightly, with between 990 and 610 taken in West Greenland and 312 to 186 in East Greenland (NAMMCO, 2014).

These figures do not include seals that were “struck and lost”, or not retrieved during the hunt.

Norway

Bearded seals were hunted commercially around Svalbard for several centuries, although they were taken more opportunistically in the hunt for other species. Currently, licensed hunters can legally catch bearded seals in Svalbard outside of the breeding season, and they take a few seals each year. Hunting of bearded seals is prohibited in all of Svalbard’s national parks or nature reserves.

Iceland

Bearded seals occasionally appear near Iceland, where local hunters opportunistically hunted by local hunters (Hauksson & Bogason, 1995).

Canada

In Canada, bearded seals are hunted year-round for subsistence purposes. This occurs from the ice in winter and from boats during the open water season. The Nunavut Wildlife Harvest Study, which ran from June 1996 to May 2001, documented hunts of from 584 to 786 bearded seals a year in Nunavut. The five year average was 735 seals (Priest & Usher, 2004).

Russia

Bearded seals have been commercially hunted by Russia in the Sea of Okhotsk and the Bering Sea, with annual catches exceeding 10,000 animals in some years during the 1950s and 1960s. There were indications of possible overexploitation in these areas, which led to a suspension of ship‐based sealing in both the Sea of Okhotsk and the Bering Sea from 1970 to 1975, and the imposition of annual total allowable catches (TACs) (Cameron et al., 2010). In 2010, the TAC for the Sea of Okhotsk was 2,100, while TACs for the White and Barents Seas in 2010 were 20 and 50 respectively, and 150 for the Kara Sea. (Cameron et al., 2010). None of the TACs include hunting for subsistence purposes.

Catches in NAMMCO member countries since 1992

| Unexpected token "end of expression" of value "" around position 1. |

|---|

This database of reported catches is searchable, meaning you can filter the information, e.g. by country, species or area. It is also possible to sort it by the different columns, in ascending or descending order, by clicking the column you want to sort by and the associated arrows for the order. By default, 10 entries are shown, but this can be changed in the drop-down menu, where you can decide to show up to 100 entries per page.

Carry-over from previous years are included in the quota numbers, where applicable.

You can find the full catch database with all species here.

For any questions regarding the catch database, please contact the Secretariat at nammco-sec@nammco.no.

EU sealskin ban and the Inuit exemption

In 1983, in response to concerns about the Canadian commercial harp seal hunt, the European Economic Community imposed an import ban on all harp seal whitecoat products. The ban, which was initially for 2 years, has been extended since then and was expanded in 2009 to include all seal products (DFO 2016).

Exceptions to the ban include products resulting from Inuit/indigenous hunts; products for the sole purpose of sustainable management of marine resources; and products for the personal use of travelers to the EU. As well, the ban does not apply to seal products trans-shipped through the EU to non-EU destinations (DFO 2016).

In order for seal products to be exempted from the ban and placed on the market in the EU the Inuit or indigenous hunt must meet certain conditions. The hunt must:

- be traditionally conducted by the community

- contribute to the community’s subsistence in order to provide food and income and not be primarily conducted for commercial reasons

- pay due care to animal welfare, while taking account of the community’s way of life and the subsistence purpose of the hunt (EUR-Lex 2016).

By-catch

By-catch, or entanglement in fishing nets or other gear, is not a significant source of mortality for bearded seals as these seals generally do not occur in areas where commercial fishing is taking place. Iceland has reported a total of 14 by-caught bearded seals between 2002 and 2018 in lumpsucker nets and gillnets (National Progress Reports Iceland). From 2002 to 2006, commercial fisheries in the Bering Sea – Aleutian Islands recorded an average annual mortality rate of one bearded seal (Cameron et al., 2010).

Struck and lost

Struck and lost refers to seals that are struck and assumed to be killed during the hunt but are not recovered. These rates vary greatly depending on the age of the seal taken, the hunter’s experience, and the weather conditions at the time of the hunt. Cameron et al., (2010) suggests struck and lost rates in the Alaskan hunt are between 25–50%. This is likely based on Cleator’s (1996) estimates that struck and lost may be up to 50% in open water and approximately 25 % on ice.

Climate change

Bearded seals are highly dependent on sea ice year-round. Stable ice pans are essential in late spring for raising pups and moulting, while summer ice is used for resting. Ice used during the pupping and nursing periods must also be located over shallow, productive waters that support a rich benthic community—providing food during this critical life stage (Kovacs et al., 2011).

© Peter Prokosch/GRID Arendal

Global climate warming is driving substantial reductions in both the extent and seasonal duration of sea ice cover in the Arctic. This poses a major threat to bearded seals and other ice-dependent marine mammals. If suitable ice floes are not available, bearded seals may lose critical pupping and nursing habitat (Hindell et al., 2012; Kovacs et al., 2011), leading to a decrease in the carrying capacity of their environment (Laidre et al., 2015). Recent modelling work shows that coastal regions, including important breeding areas in Svalbard and the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, are likely to experience some of the earliest and most severe losses of seasonal sea ice (Lacy et al., 2024).

As conditions change, bearded seals may be forced to move further north to locate suitable ice, restricting their range and potentially increasing competition for food. This may be worsened by the northward movement of temperate species into the Arctic as sea temperatures rise (Kovacs et al., 2011).

Around Svalbard, bearded seals have adapted to declining sea ice by using calved glacier ice as haul-out platforms (Lydersen et al., 2014). Although ice cover around Svalbard has declined sharply since 2006, growth rates in bearded seal pups have remained stable, likely due to their use of glacier ice for resting and nursing (Kovacs et al., 2020). In other regions, bearded seals have been observed hauling out on land during summer, which may allow them to better cope with sea ice loss than other Arctic seal species. Still, the lack of baseline data on bearded seal abundance and trends makes it difficult to assess current or future climate-related impacts on the population.

Shipping / Oil spills

Increased ship traffic poses another potential threat to bearded seals due to reduced ice cover and more open water as a consequence of climate change. The dramatic decline in Arctic Sea ice over the past few years has raised the possibility of regular cargo traffic using both the Northern Sea Route and the Northwest Passage (Laidre et al., 2015; Hovelsrud et al., 2008). Resource extraction and tourism activities will likely increase shipping traffic in the Arctic (Laidre et al., 2015; Hovelsrud et al., 2008). One example of this is the year-round shipping through Baffin Bay, planned for the Mary River iron ore project, which will affect the wintering grounds for bearded seals (NAMMCO, 2015).

Ship traffic could affect bearded seals and their habitat through their emissions and/or an accidental fuel spill. It could also affect the ecosystem by introducing invasive species or disrupt the seals themselves through the presence of enhanced movement and noise. An increase in noise in the Arctic environment could cause bearded seals to abandon areas of habitat they otherwise might use (Kovacs, 2016; Laidre et al., 2015). Increasing ship traffic could also lead to an increased risk in seals being struck by vessels.

Offshore extraction and transportation of oil and gas could affect bearded seals either through direct contact with oil from an accidental spill, or through damage to their habitat and/or prey species.

Contaminants

Contaminants transported to the Arctic from other locations, such as perfluorinated contaminants, organochlorines, and heavy metals like mercury, expose bearded seals to potential risks and environmental hazards.

Mercury in particular is a concern, as it has been found in numerous species across the Arctic in concentrations that exceed guidelines for adverse effects, and which may be increasing over time (Dietz et al., 2013). Mercury is a persistent substance that bioaccumulates in living organisms. A recent study in Alaska found both mercury and selenium in bearded seal tissues, with the highest levels found in the liver (Correa et al., 2015).

Studies have detected persistent organochlorine contaminants, including polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), Dichlorophenyltrichloroethane (DDT), and chlordane (CHL) related compounds, in the tissues of bearded seals both in the White Sea (Muir et al., 2003) and around Svalbard (Bang et al., 2001).

Bearded seals taken from the Bering and Chukchi Seas have also shown the presence of perfluorinated contaminants (PFCs), such as perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS), and related synthetic compounds. However, the levels of these compounds in bearded seals were comparatively low when compared to other species (Quackenbush & Citta, 2008).

Noise

Underwater noise in the Arctic is increasing as melting sea ice enables more human activity, including tourism, commercial fishing, oil and gas exploration, marine mining and transoceanic shipping (PAME, 2019; PAME, 2021). These activities introduce both chronic and impulsive sound sources into marine environments traditionally dominated by natural ice-related sounds.

Recent research in Svalbard has shown that human-generated noise is now a significant component of the underwater soundscape in some habitats used by bearded seals. Llobet et al. (2023) found that anthropogenic noise was present year-round in Kongsfjorden and particularly dominant during summer. The levels and types of sound differed between locations, with glacier bays and fjords exposed to tourism and vessel traffic showing much higher noise levels than more remote drift-ice sites. These sounds overlapped with the frequency range of bearded seal vocalisations, particularly those used by males during the breeding season, raising concerns about potential acoustic masking and disruption of mating behaviour.

As noise continues to increase across the Arctic, it may lead to behavioural changes, displacement from preferred habitats, and reduced communication success in bearded seals. This could have long-term implications for reproduction and survival, especially in regions with already declining sea ice availability

Greenland

The Greenland Institute of Natural Resources (GINR) conducts research on bearded seals in Greenland. Ongoing research includes analysis of sound recordings from moorings in West and East Greenland looking at seasonal distribution and movements of bearded seals, especially in relation to seismic activities (NAMMCO, 2015; National Progress Report Greenland, 2018). There has also been work on satellite tracking, and some diet samples have been collected (NAMMCO, 2016).

Greenland participated in a joint survey with Canada of the eastern part of the North Water Polynya in April 2014, to document the importance of this area for overwintering bearded seals and other marine mammals. The most recent aerial survey specifically focusing on bearded seals took place in the spring of 2018 in the North Water Polynya (National Progress Report Greenland, 2018).

Norway

In Norway, research on bearded seals is primarily carried out by the Norwegian Polar Institute, with most work focused in the Svalbard Archipelago. Over the past decades, a wide range of studies have been conducted on this species in Svalbard, covering topics such as growth and body condition, diet, movements, habitat preferences, diving behaviour, social and reproductive behaviour, pup development (ontogeny), and vocalisations.

Recent studies have highlighted year-round vocal activity in bearded seals using passive acoustic monitoring, with the most intense calling periods occurring during the breeding season in winter and spring (Mattmüller et al., 2022). Researchers have also investigated the influence of anthropogenic noise on bearded seal communication. In particular, vocalisations in fjords exposed to high levels of ship traffic, such as Kongsfjorden, may be masked by noise from tourism and transport vessels, potentially interfering with mating communication (Llobet et al., 2023).

In addition, satellite tagging of bearded seals continues to provide data on seasonal movements, haul-out behaviour, and habitat use. This ongoing work has contributed to a broader understanding of how bearded seals utilise drifting and landfast ice habitats in Svalbard, particularly in relation to pupping, moulting and feeding areas. Norwegian researchers are also involved in collaborative pan-Arctic genetic studies that aim to resolve population structure and connectivity across the species’ range.

First working group meeting currently being planned.

References

Andersen, M., Hjelset, A. M., Gjertz, I., Lydersen, C. and Gulliksen, B. (1999). Growth, age at sexual maturity and condition in bearded seals (Erignathus barbatus) from Svalbard, Norway. Polar Biology, 21, 179–185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s003000050350

Antonelis, G.A., Melin, S.R. and Bukhtiyarov, Y.A. (1994). Early Spring Feeding Habits of Bearded Seals (Erignathus barbatus) in the Central Bering Sea, 1981. Arctic, 47(1), 74–79. https://doi.org/10.14430/arctic1274

Bang, K., Jenssen, B.M., Lydersen, C. and Skaare, J.U. (2001). Organochlorine burdens in blood of ringed and bearded seals from north-western Svalbard. Chemosphere, 44(2), 193–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0045-6535(00)00197-1

Barratclough, A., Ferguson, S. H., Lydersen, C., Thomas, P. O., & Kovacs, K. M. (2023). A review of Circumpolar Arctic Marine Mammal Health—A call to action in a time of rapid environmental change. Pathogens, 12(7), 937. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens12070937

Cameron, M. F., Bengtson, J.L., Boveng, P.L., Jansen, J.K., Kelly, B.P., Dahle, S.P., Logerwell, E.A. Overland, J.E., Sabine, C.L., Waring, G.T. and Wilder, J.M. (2010). Status review of the bearded seal (Erignathus barbatus). U.S. Dep. Commer., NOAA Tech. Memo. NMFS-AFSC-211, 246 p. Available at https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/resource/document/status-review-bearded-seal-erignathus-barbatus

Charrier, I., Mathevo, N. and Aubin, T. (2013). Bearded seal males perceive geographic variation in their trills. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 67, 1679–1689. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-013-1578-6

Cleator, H.J. (1996). The status of the bearded seal, Erignathus barbatus, in Canada. Canadian Field Naturalist, 110, 501–510.

Correa, L., Castellini, J. M., Quackenbush, L.T. and O’Hara, T.M. (2015). Mercury and Selenium concentrations in skeletal muscle, liver, and regions of the heart and kidney in bearded seals from Alaska, USA. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 34(10), 2403–2408. https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.3079

Davies, C. E., Kovacs, K. M., Lydersen, C., and Van Parijs, S. M. (2006). Development of display behavior in young captive bearded seals. Marine Mammal Science, 22(4), 952–965. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-7692.2006.00075.x

Davis, C.S., Stirling, I., Strobeck, C. and Coltman, D.W. (2008). Population structure of ice‐breeding seals. Molecular Biology, 17(13), 3078‐3094. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.03819.x

Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO). (2016). 2011-2015 Integrated Fisheries Management Plan for Atlantic Seals. http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/fm-gp/seal-phoque/reports-rapports/mgtplan-planges20112015/mgtplan-planges20112015-eng.htm

Dietz, R., Sonne, C., Basu, N., Braune, B., … and Aars, J. (2013). What are the toxicological effects of mercury in Arctic biota? Science of the Total Environment, 443, 775–790. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.11.046

Dixon, B. R., Parrington, L.J., Parenteau, M., Leclair, D., Santín, M. and Fayer, R. (2008). Giardia duodenalis and Cryptosporidium spp. in the intestinal contents of ringed seals (Phoca hispida) and bearded seals (Erignathus barbatus) in Nunavik, Quebec, Canada. Journal of Parasitology, 94(5), 1161‐1163. https://doi.org/10.1645/GE-1485.1

EUR-Lex. (2016). Access to European Union Law. Available at http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/LSU/?uri=CELEX:32009R1007&qid=1455217489306

Finlay, K. and Evans, C. R. (1983). Summer Diet of the Bearded Seal (Erignathus barbatus) in the Canadian High Arctic. Arctic, 36(1), 82–89. https://doi.org/10.14430/arctic2246

Forbes, L. B. (2000). The occurrence and ecology of Trichinella in marine mammals. Veterinary Parasitology, 93(3–4), 321‐334. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4017(00)00349-6

Foster, G., Nymo, I., Kovacs, K., Beckmen, K., Brownlow, A., Baily, J., . . . Whatmore, A. (2018). First isolation of Brucella pinnipedialis and detection of Brucella antibodies from bearded seals Erignathus barbatus. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms, 128(1), 13–20. https://doi.org/10.3354/dao03211

Gjertz, I., Kovacs, K. M., Lydersen, C. and Wiig, Ø. (2000). Movements and diving of bearded seal (Erignathus barbatus) mothers and pups during lactation and post-weaning. Polar Biology, 23, 559–566. https://doi.org/10.1007/s003000000121

Greenland Institute of Natural Resources (GINR). (2016). Bearded seal. Available at http://www.natur.gl/en/birds-and-mammals/marine-mammals/bearded-seal/

Hamilton, C. D., Kovacs, K. M., & Lydersen, C. (2018). Individual variability in diving, movement and activity patterns of adult bearded seals in Svalbard, Norway. Scientific Reports, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-35306-6

Hammill, M., Kovacs, K.M. and Lydersen, C. (1994). Local movements by nursing bearded seal (Erignathus barbatus) pups in Kongsfjorden, Svalbard. Polar Biology, 14, 569–570. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00238227

Hauksson, E., and Bogason, V. (1995). Occurrences of bearded seals (Erignathus barbatus Erxleben, 1777) and ringed seal (Phoca hispida Schreber, 1775) in Icelandic waters, in the period 1990‐1994, with notes on their food. Council Meeting of the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea CM 1995/N:15.

Hindell, M.A., Lydersen, C., Hop, H. and Kovacs, K.M. (2012). Pre-Partum Diet of Adult Female Bearded Seals in Years of Contrasting Ice Conditions. PLoS ONE, 7(5), e38307. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0038307

Hjelset, A. M., Andersen, M., Gjertz, I., Lydersen, C., and Gulliksen, B. (1999). Feeding habits of bearded seals ( Erignathus barbatus ) from the Svalbard area, Norway. Polar Biology, 21(3), 186–193. https://doi.org/10.1007/s003000050351

Hovelsrud, G.K., McKenna, M. and Huntington, H.P. (2008). Marine mammal harvests and other interactions with humans. Ecological Applications, 18(2), S135–S147.https://doi.org/10.1890/06-0843.1

Jones, J.M., Thayre, B.J., Roth, E. H., Mahoney, M., Sia, I., Merculief, K., Jackson, C., Zeller, C., Clare, M., Bacon, A., Weaver, S., Gentes, Z., Small, R.J., Stirling, I., Wiggins, S.M., Hildebrand, J. A. and Giguère, N. (2014). Ringed, Bearded, and Ribbon Seal Vocalizations North of Barrow, Alaska: Seasonal Presence and Relationship with Sea Ice. Arctic, 67(2), 203–222. https://doi.org/10.14430/arctic4388

Kovacs, K. M., Krafft, B. A., & Lydersen, C. (2020). Bearded seal ( Erignathus barbatus ) birth mass and pup growth in periods with contrasting ice conditions in Svalbard, Norway. Marine Mammal Science, 36(1), 276–284. https://doi.org/10.1111/mms.12647

Kovacs, K. M., Krafft, B. A., and Lydersen, C. (2019). Bearded seal ( Erignathus barbatus ) birth mass and pup growth in periods with contrasting ice conditions in Svalbard, Norway. Marine Mammal Science, 36(1), 276–284. https://doi.org/10.1111/mms.12647

Kovacs, K.M. (2016). Erignathus barbatus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T8010A45225428. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T8010A45225428.en.

Kovacs, K.M., Lydersen, C. and Gjertz, I. (1996). Birth-site characteristics and prenatal molting in bearded seals (Erignathus barbatus). Journal of Mammalogy, 77(4), 1085–1091. https://doi.org/10.2307/1382789

Kovacs, K.M., Moore, S., Overland, J.E. and Lydersen, C. (2011). Impacts of changing sea-ice conditions on Arctic marine mammals. Marine Biodiversity, 41, 181–194. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12526-010-0061-0

Lacy, R. C., Kovacs, K. M., Lydersen, C., & Aars, J. (2024). Linking PVA models into metamodels to explore impacts of declining sea ice on ice-dependent species in the Arctic: the ringed seal, bearded seal, polar bear complex. Frontiers in Conservation Science, 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcosc.2024.1439386

Laidre, K.L., Stern, H., Kovacs, K.M., Lowry, L., … and Ugarte, F. (2015). Arctic marine mammal population status, sea ice habitat loss, and conservation recommendations for the 21st century. Conservation Biology, 29(3), 724–737. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12474

Llobet, S. M., Ahonen, H., Lydersen, C., & Kovacs, K. M. (2023). The Arctic and the future Arctic? Soundscapes and marine mammal communities on the east and west sides of Svalbard characterized through acoustic data. Frontiers in Marine Science, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2023.1208049

Llobet, S. M., Ahonen, H., Lydersen, C., Berge, J., Ims, R., & Kovacs, K. M. (2021). Bearded seal (Erignathus barbatus) vocalizations across seasons and habitat types in Svalbard, Norway. Polar Biology, 44(7), 1273–1287. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00300-021-02874-9

Lydersen, C. and Kovacs, K. M. (1999). Behaviour and energetics of ice-breeding, North Atlantic phocid seals during the lactation period. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 187, 265–281. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps187265

Lydersen, C., Assmy, P., Falk-Petersen, S., Kohler J., … and Zajaczkowski, M. (2014). The importance of tidewater glaciers for marine mammals and seabirds in Svalbard, Norway. Journal of Marine Systems, 129, 452–471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmarsys.2013.09.006

Lydersen, C., Hammill, M.O. and Kovacs, K.M. (1994). Diving activity in nursing bearded seal (Erignathus barbatus) pups. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 72(1), 96–103. https://doi.org/10.1139/z94-013

Lydersen, C., Kovacs, K.M., Hammill, M.O. and Gjertz, I. (1996). Energy intake and utilization by nursing bearded seal (Erignathus barbatus) pups from Svalbard, Norway. Journal of Comparative Physiology B, 166, 405–411. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02337884

MacIntyre, K.Q., Stafford, K.M., Berchok, C. L. and Boveng, P.L. (2013). Year-round acoustic detection of bearded seals (Erignathus barbatus) in the Beaufort Sea relative to changing environmental conditions, 2008–2010. Polar Biology, 36, 1161–1173. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00300-013-1337-1

Marshall, C.D. (2016). Morphology of the bearded seal (Erignathus barbatus) muscular– vibrissal complex: a functional model for phocid subambient pressure generation. The Anatomical Record, 299(8), 1043–1053. https://doi.org/10.1002/ar.23377

McCarthy, M. L., Martínez, A. R., Ferguson, S. H., Rosing‐Asvid, A., Dietz, R., De Cahsan, B., Schreiber, L., Lorenzen, E. D., Hansen, R. G., Stimmelmayr, R., Bryan, A., Quakenbush, L., Lydersen, C., Kovacs, K. M., & Olsen, M. T. (2025). Circumpolar population structure, diversity and recent evolutionary history of the bearded Seal in relation to past and present icescapes. Molecular Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.17643

Mizuguchi, D., Tsunokawa, M., Kawamoto, M. and Kohshima, S. (2016). Sequential calls and associated behavior in captive bearded seals (Erignathus barbatus). Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 140(4), 3238–3238. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.4970242

Muir, D., Savinova, T., Svinov, V., Alexeeva, L., Potelov, V. and Svetochev, V. (2003). Bioaccumulation of PCBs and chlorinated pesticides in seals, fishes and invertebrates from the White Sea, Russia. Science of the Total Environment, 306(13), 111–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-9697(02)00488-6

North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO). (2009). Annual Report 2007‐2008. NAMMCO, Tromsø, Norway. 399 p. https://nammco.no/topics/annual-reports/

North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO). (2014). Annual report 2014. NAMMCO, Tromsø, Norway. 246 p. https://nammco.no/topics/annual-reports/

North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO). (2015). Annual report 2015. NAMMCO, Tromsø, Norway. 374 p. https://nammco.no/topics/annual-reports/

North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO). (2016). Report of the 23rd of the Scientific Committee Meeting, Nuuk, Greenland, 4-7 November. 291 pp. https://nammco.no/topics/scientific-committee-reports/

PAME, Underwater Noise in the Arctic: A State of Knowledge Report, Roveniemi, May 2019. Protection of the Arctic Marine Environment (PAME) Secretariat, Akureyri (2019)

PAME, Underwater Noise Pollution from Shipping in the Arctic, Protection of the Arctic Marine Environment Working Group (PAME), May 2021.

Priest, H. and Usher, P.J. (2004). The Nunavut Wildlife Harvest Study. Nunavut Wildlife Management Board. 816 p. Available at https://www.nwmb.com/inu/publications/harvest-study/1824-156-nwhs-report-2004-156-0003/file

Quackenbush, L.T. and Citta, J.J. (2008). Perfluorinated contaminants in ringed, bearded, spotted, and ribbon seals from the Alaskan Bering and Chukchi Seas. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 56(10), 1802–1814. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2008.06.005

Risch, D., Clarke, C.W., Cockeron, P.J., Elepfandt, A., Kovacs, K.M., Lydersen, C., Stirling, I. and Van Parijs, S.M. (2007). Vocalizations of male bearded seals, Erignathus barbatus: classification and geographical variation. Animal Behavior, 73(5), 747–762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2006.06.012

Sardi, K. A. and Merigo, C. (2006). Erignathus barbatus (Bearded seal) Vagrant in Massachusetts. Northeastern Naturalist, 13(1), 39–42. https://doi.org/10.1656/1092-6194(2006)13[39:EBBSVI]2.0.CO;2

Stewart, D.B. and Lockhart, W.L. (2005). An overview of the Hudson Bay Marine Ecosystem. Canadian Technical Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 2586, vi + 487 p. https://waves-vagues.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/Library/314704covermaterial.pdf

Van Parijs, S. M., Lydersen, C. and Kovacs, K. M. (2003). Vocalizations and movements suggest alternative mating tactics in male bearded seals. Animal Behaviour, 65(2), 273–283. https://doi.org/10.1006/anbe.2003.2048

Van Parijs, S., Kovacs, K., & Lydersen, C. (2001). Spatial and temporal distribution of vocalising maile bearded seals – Implications for male mating strategies. Behaviour, 138(7), 905–922. https://doi.org/10.1163/156853901753172719

Van Parijs, S.M. and Clark, C.W. (2006). Long-term mating tactics in an aquatic-mating pinniped, the bearded seal, Erignathus barbatus. Animal Behaviour, 72(6), 1269–1277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2006.03.026

Van Parijs, S.M., Lydersen, C. and Kovacs, K.M. (2004). The effects of ice cover on the behavioural patterns of aquatic mating male bearded seals. Animal Behavior, 68(1), 89–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2003.09.013

Norwegian Polar Institute – Bearded seal

Greenland Institute of Natural Resources – Bearded seal

Canadian Dept of Fisheries and Oceans – Bearded seal

US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Fisheries -Bearded seal

Alaskan Department of Fish and Game – Bearded seal

Seal Conservation Society – Bearded seal

Ocean Conservation Research – Bearded seal (including audio recordings of vocalisations)

Discovery of Sound in the Sea – Bearded seal vocalisations

VIDEOS: