Ringed Seal

Latest update: September 2024 (reviewed by the Scientific Committee)

The ringed seal (Pusa hispida) is among the smallest of the phocid seals. The species consists of five subspecies, of which the Arctic ringed seal (Pusa hispida hispida) is the most widespread and abundant. It is the only subspecies in the NAMMCO countries.

The ringed seals are generally most abundant in areas with ice and they play an important role in the high Arctic ecosystems. Their ability to make and maintain breathing holes allows them to spread out in ice covered areas where other marine mammals have no or limited access. Another speciality is their ability to make lairs that protect them and their pups against the cold weather, and in some cases, also allows for some reaction time in the case of polar bear attacks. The name of the ringed seal refers to the light-coloured rings on the dark-coloured back.

ABUNDANCE

The overall number of ringed seals is very uncertain but various estimates (Laire et al. 2015, Kovacs et al. 2021 and NMFS. (2024)) indicate a total number of about 3.5 million seals of which a little more than 3 million are of the Arctic subspecies Pusa hispida hispida.

DISTRIBUTION

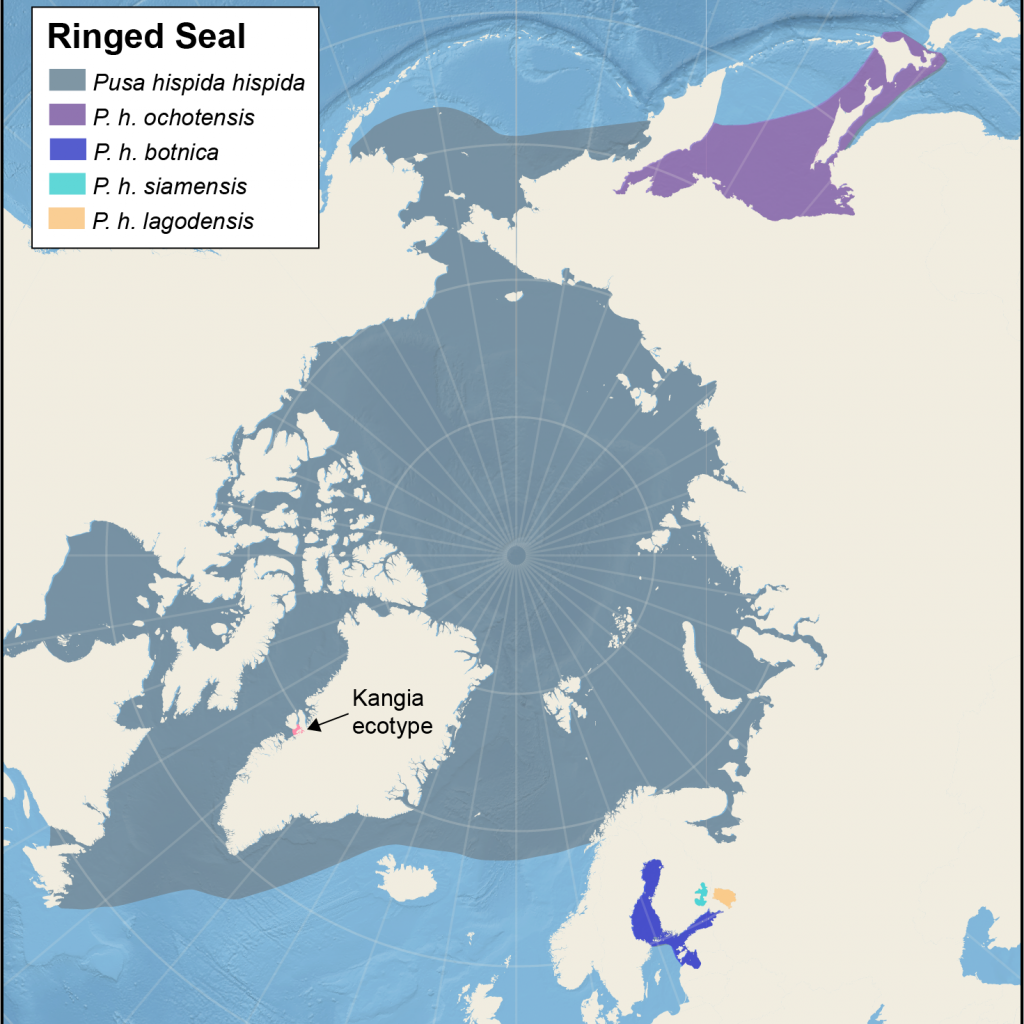

The Arctic Ringed seals have a circumpolar distribution throughout the Arctic, whereas the other sub species occupy The Sea of Okhotsk, The Baltic Sea and Lake Ladoga (Russia) and lake Saimaa (Finland).

RELATION TO HUMANS

Ringed seals have traditionally been hunted by indigenous peoples from Alaska, Canada, Greenland, and Russia for food and skin. Nowadays, there is also a limited sport hunting in northern Norway.

CONSERVATION AND MANAGEMENT

There are both national and regional management regimes.

A hunting licence is required in Canada, Greenland, and Russia, but there is no restriction on season or numbers that can be taken. Hunting is closed in Svalbard during the breeding season and there is a quota system for sport hunters in northern Norway. In Greenland it is prohibited to hunt pups with lanugo hair and nursing females.

At present there is little evidence of depletion, but the species is likely to be challenged by the impacts of climate change, with a predicted reduction in distribution range and numbers.

In the most recent assessment (2016) the species is listed as ‘Least Concern’ on the global IUCN Red List. The species is listed as ‘Vulnerable’ on the Norwegian national red list (2021) and as “Least Concern” in the Greenlandic Red List (2018).

LIFESPAN

Up to 45 years (Lydersen 1998)

AVERAGE SIZE

A study comparing morphometric data of ringed seals from 35 different locations in the Arctic found the asymptotic lengths varied from 113 cm to 151 cm. The sexes differed in length at some locations, but not in a consistent pattern of dimorphism (Kovacs et al. 2021). Ringed seals are sometimes referred to as the smallest of the seal species, but although the smallest of seals are likely to be found among the ringed seals, some habitats have ringed seals that become larger than the Baikal seal (Pusa sibirica) and the Caspian Seal (Pusa capsica), and are more similar in size with the Harbour seal (Phoca vutulina).

MIGRATION AND MOVEMENTS

Ringed seals are generally associated with areas that have ice, but low densities may also be found in areas without ice. Telemetry studies especially in high Arctic waters show that adult seals are more sessile than pups and juveniles (Yurkowski 2016). The adults tend to stay or return to certain breeding areas, that have stable ice-conditions, whereas pups tend to move to areas with relatively light ice-conditions, where they don’t have to maintain breathing holes in thick ice. Some pups are known to have returned as adult to the area where they were born, but how regularly this happens is unknown.

FEEDING

Ringed seals are opportunistic feeders, preying on a wide variety of fish, crustaceans, and cephalopods, with polar cod typically the most common prey in areas with many ringed seals. This goes for both juvenile and adults, although younger seals tend to feed more heavily on crustaceans, especially on amphipods, mysidae, and euphausiids. There are important regional and seasonal differences in diet, reflecting habitat-specific prey availability (Kelly et al. 2010b, Kovacs 2014).

GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS

The ringed seal belongs to the family of true seals, also called phocids, which are earless seals. Ringed seal pups are born with white woolly lanugo hair, which they begin shedding at about 2 months of age. Thereby, they reveal the underlying pelage, which can vary significantly between areas. Generally, however, their coats are light (silver-grey) on their belly, with a dark back, most often with a pattern of light rings. In some areas young and adult seals have a very similar pelage, but in other areas they seem to acquire more or more conspicuous rings gradually with age.

The ringed seal body is fusiform in shape (i.e. tapering at both ends). In winter, when seals are the fattest, their girth can exceed 80% of the body length (Reeves et al. 1992). Their muzzle is short and their head cat-like. The male’s faces might appear to be darker than those of females because of an oily secretion from glands in the facial region. This is often related to the rut in spring when the smell and the taste of their meat also change significantly. These seals are called tiggaq by inuit. In some areas the tiggaq might also occur during late fall and winter in areas where the seals make territories.

The fore-claws of young 0-1½ year-old seals are usually unworn and pointed (indicating that they haven’t stayed in heavy/thick ice during their first winter). The claws of adult seals are often worn down because these seals often maintain breathing holes in thick stable ice.

Pups are born with a full complement of permanent adult teeth.

Young ringed seal pup from Northwest Greenland (still with a few lanugo hair on its back) © Aqqalu Rosing-Asvid

Subspecies and ecotype

Ringed seals are divided into five subspecies on the basis of geographical isolation:

- Pusa hispida hispida of the Arctic Ocean and adjacent waters (the Arctic ringed seal)

- P. hispida ochotensis of the Sea of Okhotsk and northern Japan

- P. hispida botnicaof the Baltic Sea

- P. hispida ladogensisof Lake Ladoga in Russia

- P. hispida saimensisof Lake Saimaa in Finland

The subspecies Pusa hispida hispida, is the Arctic ringed seal, which can be encountered in all parts of the Arctic and in some adjacent waters. It is the only subspecies present in the NAMMCO area and the focus of the information presented on this website.

In 2023 what appears to be a ringed seal ecotype was described. This ecotype is mainly residing in Kangia (Ilulissat Icefjord) in central West Greenland. An ecotype, unlike the subspecies, is not geographically separated from other ringed seals. They may live in proximity of other ringed seals, but they differ genetically and remain different. This ecotype in Kangia has a very high degree of site fidelity and seems to “monopolise” the fjord. Their pelage is somewhat different from that of other ringed seals, and they are larger in size. Genomic analysis reveal that they diverged from the Arctic ringed seals about 240 thousand years ago and lived isolated until the last glacial maximum about 20.000 years ago. It is unknown where these seals have been isolated, but it is speculated that it has been in one of the side-fjords to Kangia, which get blocked as the glacier expands. (Rosing-Asvid et al., 2023). An aerial survey in 2018 estimated this population to number around 3000 seals that due to their genetic uniqueness and isolation will be treated as a separate management unit.

LIFE HISTORY AND ECOLOGY

Survival rates are not well known but ringed seals are relatively long-lived and can live to be more than 40 years old (McLaren 1958, Lydersen 1998). Their average life span is about 15–28 years (Kelly et al. 2010b).

Female ringed seals may reach sexual maturity at age 3–5, but due to geographic and temporal variability in condition and population structure, some do not mature until they are 7–8 years old (Reeves 1998, Sipilä & Hyvärinen 1998, Krafft et al. 2006b, Kovacs et al. 2008, Kelly et al. 2010b, Kovacs 2014).

Ringed seal females usually produce a single pup each year, although this may not happen if conditions are not favourable (Kingsley and Byers 1998, Kovacs et al. 2008, Kelly et al. 2010). Reproductive success depends on many factors including prey availability, the relative stability of ice, and sufficient snow accumulation prior to the commencement of breeding so that the birth lair can be constructed (Kovacs et al. 2008).

Males mature about 2 years later than females at 5–7 years (Krafft et al. 2006b, Kelly et al. 2010b) and likely do not participate in breeding before they are between 8–10 years old (Kovacs et al. 2008).

MOULTING

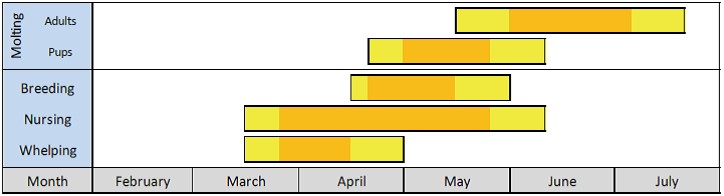

Approximate annual timing of reproduction and moulting for Arctic ringed seals (from Kelly et al. 2010b). Yellow bars indicate the “normal” range over which each event is reported to occur and orange bars indicate the “peak” timing of each event.

Ringed seals can begin to moult as early as late April, with the number of moulting seals increasing in May and peaking in June. The seals spend a lot of time (up to 60%) hauled out on ice basking in the sun both prior and during moulting. This behaviour is attributed to the need to maintain an elevated skin temperature (Kelly et al. 2010ab). Feeding activity is at a minimum during the spring moult and ringed seals lose a lot of weight and are therefore thin in the summer (Ryg et al. 1990, Rosing-Asvid 2010). Consequently, they sink more easily when hunted in the early summer. In August–September, they begin to put on weight again and by December, they have returned to their maximum weight.

Feeding

The diet of ringed seals has been well documented across the species’ range (Belikov & Boltunov 1998, Lyersen 1998, Siegstad et al. 1998, Wathne et al. 2000, Holst et al. 2001, Andersen et al. 2004, Carlsen et al. 2006, Stenman and Pöyhönen 2005, Dehn et al. 2007, Agafonova et al. 2007, Labansen et al., 2007, 2011, Vincent-Chambellant 2010, Kelly et al. 2010b, Kovacs 2014 and 2020).

Ringed seals are opportunistic feeders and prey on a wide variety of fish and invertebrates, but strong preferences for particular types of prey are evident. Diet is thus determined by the combination of preferences and the regional and seasonal availability of various type of prey. Gadoid fishes dominate the diet at least from late autumn through the spring in many areas, with polar cod (Boreogadus saida) being the most commonly consumed species. This small fish occurs both in ice-free and ice-covered waters, especially at the ice edge, where young polar cod sometimes can be found in spaces within the sea ice. Other gadoid fish are also seasonally important in some areas, such as Arctic saffron cod (Eleginus gracilis) in the Pacific, and navaga (Eleginus nawaga) in the eastern part of the Atlantic. Other prey found important in some areas are redfish (Sebastes sp.), capelin (Mallotus villosus), herring (Clupea sp.) and pricklebacks (Stichaeidae).

Invertebrates, both crustaceans and cephalopods, become more important in most areas during the open-water season. Ringed seals around Greenland are most abundant in the ice-filled regions of North and East Greenland, where the bulk of the diet often is polar cod and Themisto (a kind of amphipod).

Fresh Themisto specimen. © Pinngortitaleriffik

Preferred prey size

Most ringed seal prey is small and preferred prey tend to be schooling species that form dense aggregations. Fishes are usually in the 5–10 cm range and crustacean prey in the 2–6 cm range, but larger prey may be taken on occasion. Typically, ringed seals prey upon no more than 10–15 species in any one area, with 2–4 species considered as important prey.

Differences in prey composition

There seem to be age- and sex-related differences in prey composition. Adult ringed seals prefer to feed on pelagic schooling fish in most areas, while younger animals feed heavily on smaller prey such as amphipods, euphausiids, and mysidae. Ringed seals do also feed on demersal fish and shrimps. In that relation, adult males are able to dive deeper than pregnant females, which can create a difference between the sexes in the dive and feeding patterns.

Competition with other species

Ringed seals are normally the only Arctic seal that regularly maintains breathing holes in areas with thick winter ice. Bearded seals also maintain breathing holes in some regions, but vast areas of habitat are not used by other seals than ringed seals during winter. The competition with other seal species is in the NAMMCO area mainly with harp seals (Pagophilus groenlandicus) that migrate into ringed seal habitat during the open water season, and forage along the pack ice and land-fast ice zones during winter. Especially polar cod and capelin are consumed by both seal species. Belugas (Delphinapterus leucas), narwhals (Monodon monoceros) and bowhead whales (Balaena mysticetus) are also mainly summer competitors, but they also move into relatively loose pack ice and relatively thin winter ice and together with bearded seals and young ringed seals some of them winter in polynyas.

Predators

Polar bears (Ursus maritimus) are by far the most important predator of ringed seals (Kelly et al. 2010, Kovacs 2014). They kill seals at their breathing holes or in their subnivean lairs (i.e. lairs in the area between the surface of the ground and the bottom of the snowpack) by crashing through the snow roof. They also stalk seals lying on the ice in the spring and summer, in ice cracks, and even in open water. Polar bears tend to be most successful at killing pups and sub-adult seals, but adult seals are also taken.

Ringed seals are also preyed upon by walrus (Odobenus rosmarus), killer whales (Orcinus orca), glaucous gulls (Larus hyperboreus) and Greenland sharks (Somniosus microcephalus) (Lydersen 1998, Ridoux et al. 1998, Kelly et al. 2010b, Leclerc et al. 2012, Lydersen & Kovacs 2013, Remili et al. 2023). In addition, pups are taken by Arctic (Alopex lagopus) and red (Vulpes vulpes) foxes, wolves (Canis lupus), wolverines (Gulo gulo) ravens (Corvus corax), and dogs in the spring (Reeves 1998, Kelly et al. 2010b, Kovacs 2014).

Health and Parasites

Many different parasites have been detected in ringed seals, the most common being helminths in the gastro-intestinal tract (Kelly et al. 2010 and Kovacs 2014). In Svalbard, the abundance of nematodes and acantocephalans in the digestive tract varies with sampling location and seal age and sex, influenced by the fish availability as prey and the age class exploited by the different seal groups (Johansen et al. 2010). Parasite burdens can be quite high in ringed seals, although they seldom debilitate healthy seals.

Distribution

Ringed seals occur throughout the Arctic, north to the pole if it is without multi-year ice. They are the only northern seal that regularly maintain breathing holes in thick sea ice (over 1 m in thickness). This special ability allows them to have an extensive distribution in the Arctic and sub-Arctic and to thrive in areas where even other ice associated seals cannot reside.

In the North Atlantic, the ringed seal occurs in marine areas virtually everywhere where there is seasonal ice cover (Reeves 1998, Kelly et al. 2010b, Kovacs 2014), as they cannot make breathing holes in multi-year ice. Their global distribution has expanded and contracted with changing sea‐ice cover, and today they inhabit close to all the seasonally ice‐covered seas of the Northern Hemisphere, as well as some fresh-water lakes.

Distribution of different subspecies of ringed seals

In the Western Atlantic, the Arctic ringed seals (Pusa hispida hispida) occur as far south as Newfoundland, northward to the pole and throughout the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. They occur throughout Greenland waters but are generally most abundant in areas with sea ice. Ringed seals occur around Svalbard and Franz Josef Land and are occasionally encountered in the Faroe Islands and northern Iceland. In the Eastern Atlantic, ringed seals inhabit the entire Eurasian Arctic coast, including the coastal waters of the White Sea and southeastern Barents Sea. The subspecies Pusa hispida botnica live in the Gulf of Bothnia, and in the Baltic Sea. Two other subspecies live in freshwater (in Lake Ladoga in Russia and Lake Saimaa in Finland) (Sipilä & Hyvärinen 1998). In Nunavut, Canada ringed seals live in Nettilling Lake, but these seals do not have status as subspecies.

Extralimital records extend far south on both sides of the Atlantic, to New Jersey in the west and to France and Portugal in the east (Ridoux et al. 1998). A young seal tagged in Brittany in France, was found one year later in a Greenland shark stomach off Iceland, showing that at least some of these, usually young, vagrants may have the navigational skills to return to normal habitat (Ridoux et al. 1998).

Habitat and Movements

The ringed seal is the species most strongly associated with ice, and therefore has the best adaptations to living on ice. Throughout most of its range, it does not come ashore and uses sea ice as a substrate for resting, pupping, and moulting (Kelly et al. 2010a). It comes out of the water exclusively on sea ice, except in marginal seas and freshwater lakes where ice disappears seasonally.

Ringed seals occur in areas of land-fast and drifting pack ice over virtually any water depth. While some may prefer areas of land-fast ice for breeding, others breed successfully in areas of stable pack ice, such as Baffin Bay and the Greenland Sea. Unlike other northern seals, such as harp and hooded seals, their breeding areas are spread out in many parts of the ice-covered waters of the Arctic.

© K.M. Kovacs, Norwegian Polar Institute

The young of the year and, to some degree, other juvenile ringed seals tend to move away from areas with heavy ice formation, which forces them to make breathing holes. This results in a general movement of young seals out of some fjords in early winter, and a general movement from high Arctic areas toward less severe conditions in polynyas or in more southern areas. These movements of young seals, to some extent, resemble a migration pattern.

Adult seals are generally more sessile than young seals (Yurkowski et al. 2016). They prefer to stay in stable ice although that involves the maintenance of breathing holes. One ringed seal is able to maintain several breathing holes in ice that may be over 1 m in thickness by using their strong fore-claws and teeth to scratch through the ice.

In the summer and fall, when land-fast ice is not available, ringed seals show considerable diversity in their distribution patterns (Kovacs 2014). Some animals remain in the general vicinity of their breeding sites, while others disperse along coastlines, or concentrate their time near glacier fronts. Some spend time in open water far from the coast, while others move north to the southern edge of the permanent ice (Teilmann et al. 1999, Gjertz et al. 2000, Born et al. 2002, Freitas et al. 2008a).

During the fast-ice seasons, each ringed seal might use several haul-out lairs and additional breathing holes within its home range and travel between them quite regularly. A seal’s lairs are usually only a few hundred meters apart, although on average, the lairs of males are spread over greater distances than those of females. During the reproductive season, females spend more time on average out of the water than males, and both sexes shift from hauling out during the night in early spring to hauling out during the day in late spring, with more time spent on the surface during the latter period (Kelly & Quakenbush 1990, Carlens et al. 2006).

It is unclear to what extent ringed seals show fidelity to natal sites or are faithful to breeding sites as adults. It is also not clear to what extent this depends on the quality of the sites (predictable ice stability, sufficient snow to construct lairs, good food availability), or whether there are regional and subpopulation differences. Prime habitat for ringed seals may be used over long periods of time, but there are also reports that strongly suggest that there is considerable mobility among ringed seals in some areas (Kovacs 2014). Ringed seals have, however, shown a high degree of spatial fidelity (territoriality) in the Baltic (Härkönen et al. 2008).

Ringed seals can travel significant distances, well over 1000 km (e.g., Kapel et al.1998, Ridoux et al. 1998). However, most satellite tracking studies show that individuals tagged at any one location display variable dispersal patterns, with some individuals remaining local throughout the open-water season, while others move offshore or northward to the permanent pack-ice (Teilmann et al. 1999, Gjertz et al. 2000, Born et al. 2004).

The seasonality of ice cover strongly influences ringed seal movements, as well as foraging, reproductive behaviour, and vulnerability to predation (Kelly et al. 2010b).

MANAGEMENT AREAS AND SUBSPECIES

On the basis of geographical isolation, ringed seals have been divided into five subspecies: Pusa hispida hispida of the Arctic Ocean (the Arctic ringed seal), P. hispida ochotensis of the Sea of Okhotsk and northern Japan, P. hispida botnica of the Baltic Sea and the two last living in fresh-water lakes, P. hispida ladogensis of Lake Ladoga in Russia, P. hispida saimensis of Lake Saimaa in Finland. The distribution of the Arctic ringed seal (Pusa hispida hispida) is virtually continuous and there are few geographical barriers that would prevent their dispersion. Indeed, individual tagged ringed seals have been shown to move very long distances on occasion (Kapel et al. 1998, Ridoux et al. 1998, Teilmann et al. 1999). As an example, from seals tagged in Resolute Bay three individuals travelled about 2,500 kilometres to southeast Baffin Island, and another covered 3,000 kilometres, swimming to Frobisher Bay via Greenland (Yurkowski et al. 2016).

The biodiversity within and among the closely situated Baltic, Saimaa, and Ladoga subspecies is not fully understood. A recent study show that the clade of Saimaa ringed seals is not nested within the Baltic haplotypes from which they were thought to have originated. Rather, the Saimaa seals are nested more within the Arctic group (Heino et al. 2023).

Map showing the five management areas for Arctic ringed seals, and the location of the ecotype from Kangia. The map also shows four non-Arctic subspecies

The NAMMCO Scientific Committee Working Group on Ringed Seals used published genetic and movement data to define areas with little or no interactions with neighbouring areas and came up with: (1) Svalbard, (2) East Greenland, (3) West Greenland and East Canadian waters, (4) Hudson Bay, (5) West Canada, Beaufort Sea, Chukchi and Bering Seas, and last, the Kangia ecotype (NAMMCO, 2023). Data from the border between unit 3 and 5 are few and the boundary between those areas are therefore not conclusive. Also, one juvenile seal has been tracked from East Greenland (2) to Labrador (3) showing some contact between these areas.

These areas can be used as management units that give an idea about which country is responsible for the management. Norway don’t seem to share ringed seals with other countries, but the ringed seals in eastern Canada and western Greenland should be managed as one unit. There might be sub populations within a management unit, which haven’t been recognized yet. The newly described Kangia ecotype, is an example of a small but well-defined unit that will have to be managed individually.

Current Abundance and Trends

Ringed seals are the most abundant high arctic seal and although no accurate global estimate is available, the species is thought to number at least a few million animals (Reeves 1998).

Counting ringed seals

Ringed seals are difficult to count. Other ice breeding seals, such as harp (Pagophilus groenlandicus) and hooded (Cystophora cristata) seals, give birth and nurse their pups on the surface of the ice in highly concentrated patches. Aerial surveys for these species are conducted to count the pups during breeding season and pup counts are then converted to total population estimates. Ringed seals give birth in lairs under the snow, which are practically invisible from the ice surface. While they commonly haul out on the ice during the moulting period in late spring, it is unlikely that the entire population would be on the ice surface at any given time. Aerial, ground- or ship-based surveys can detect only those seals that are on the ice or at the surface of the water and this proportion is usually unknown. Therefore, estimates of ringed seal abundance are not available for most areas.

Despite these difficulties, aerial surveys of fast-ice areas during the spring have been conducted and are the most widely used method of assessing the abundance of ringed seals, although it is widely recognized that such counts are underestimates (see Reeves 1998, and more recently e.g. Frost et al. 2004, Moulton et al. 2005, Bengtson et al. 2005, Krafft et al. 2006a). Surveys must be timed to coincide with peak haul-out season and correction factors are still required to account for the number of animals that are not visible at the time of the survey because they are either in the water, or in some cases, still in their snow lairs.

A variety of methods have been employed to attempt to correct counts to population estimates (Reeves 1998, Bengtson et al. 2005, Kelly et al. 2006, Krafft et al. 2006a) but calibration issues remain (Carlens et al. 2006, Krafft et al. 2006a). Most if not all abundance surveys to date should probably be considered indices of abundance (Kovacs & Lydersen 2006, Kovacs 2014).

A dog sniffing out a ringed seal lair during counts of ringed seals in Alaska. © University of Southeast Alaska

Counts of breathing holes and/or birth lairs using trained dogs have also proven to be an effective method in some areas (Hammill & Smith 1990, Lydersen 1998). Some estimates of abundance have also been derived by calculating the number of ringed seals required to support the predation of polar bears and humans in the area. The abundance of polar bears is usually more accurately known than the abundance of ringed seals. For example, Kingsley (1998) used a population estimate for polar bears in Baffin Bay, estimates of their food requirements, and the human hunt by Canada and West Greenland, to estimate that there must be at least 1.2 million ringed seals in the area to support this level of predation.

The remoteness and dynamic nature of ringed seal sea‐ice habitat, time spent below the surface, along with their broad distribution and seasonal movements makes surveying ringed seals expensive and logistically challenging. It is therefore very difficult to assess their population size and trend (Kelly et al. 2010b).

There is no new available abundance assessment for any of the NAMMCO management areas, except for the estimate of approximately 3000 Kangia seals in the Ilulissat Icefjord in Greenland (Rosing-Asvid et al. 2023).

ABUNDANCE AND TRENDS

Because of the difficulties in deriving estimates of abundance, there is little information on trends in abundance for most areas.

Short-term fluctuations in the numbers of young seals produced have been documented (e.g. Kingsley and Byers 1998) and are likely related to annual variations in snow and ice conditions. Seasonal reductions in abundance in the vicinity of hunting communities have also been noted (Reeves 1998). The only areas where population reductions definitely can be related to over-hunting have been in the Okhotsk Sea and the Baltic Sea. Both these areas were subject to large-scale commercial hunting in the past. This hunting has since been reduced (Okhotsk Sea) or ceased (Baltic Sea).

Ringed seal abundance and conservation status

| Areas | Year | Estimate | Status of ‘populations’ | Causes // Concerns | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arctic ringed seal | A few million | Least concern (IUCN Red list) | Large population size, broad distribution // Climate change | Reeves, 1998; Kovacs et al., 2008 | |

| Canadian Arctic Archipelago | N/A | Unknown | |||

| Greenland Sea & Baffin Bay | 1979 | 787,000 | Stable since 1979 | Large population size, broad distribution // Climate change | Finley et al., 1983 |

| Hudson Bay, western part | 1995 | 280,000 | Lunn et al., 1997 | ||

| 2007-08 | 53,400 on ice | Ferguson & Secretariat, 2009 | |||

| Beaufort & Chukchi Seas | from 1981 | 1,000,000, incl. pack ice | Kelly et al., 2010b, based on several surveys | ||

| White, Barents & Kara Seas | from 1975 | 220,000 | |||

| Russian Arctic coast | N/A | Unknown | |||

| Okhotsk ringed seal | 1968-90 | 676,000 – 855,000 | Likely stable | Hunting // Climate change | Fedoseev, 2000 |

| Baltic ringed seal | 1996 | 10,000 | Dramatic ↓ until the 1970s. Presently ↑ in Bothnia Bay, ↓ in the Gulf of Riga, stable in the Gulf of Finland | Swedish & Finnish extermination efforts, low fertility due to organochlorines // Climate change | Härkönen et al., 1998, 2008; Harding & Härkönen, 1999; Karlsson et al., 2007 |

| Lagoda ringed seal | 2001 | 3,000 – 5,000 | ↓ | By-catch // Climate change | Verevkin, 2002; Agafonova et al., 2007 |

| Saimaa ringed seal | 2005 | < 300 (1) | ↓ | By-catch // Climate change | Sipilä, 2006; Sipilä & Kokkonen, 2008 |

Stock Status

ARCTIC RINGED SEALS

Kovacs et al. (2021) compiled available survey-results of Arctic ringed seals from 10 different regions. This summed up to about 2.5 million seals, but in addition there were 5 more regions for which there were no estimates. Most surveys were old (some back to the 1970s), so the data might not reflect the current status, but it gives an idea about the potential number of seals.

A large fraction of these Arctic ringed seals occupy areas of pack ice that are extremely remote and inaccessible to hunters. Even large proportions of the coastal areas are only rarely visited, and these factors decrease the vulnerability to overexploitation. Hunting in Canada, Greenland and Russia have been sustained for hundreds of years without evidence of depletion.

Hunting statistics in Svalbard show less than 100 seals caught yearly since 2002 (NAMMCO, 2023) and this small catch is found to be neglectable. The available catch statistics from Alaska and Canada indicate a declining trend in catch numbers, which likely is related to lower interest in hunting of the newer generations.

In the (2) East Greenland and (3) West Greenland and East Canadian waters, there have been a major decline in ringed seal catches (more than 60% and 50%, respectively since 2005). The reason for these declines is unclear, but likely candidates are more focus on fisheries compared to hunting, decline in the number of sled dogs (less meat needed), more polar bears after the introduction of quotas (in 2006) and possibly a decline in the size and quality of their habitat due to climate changes.

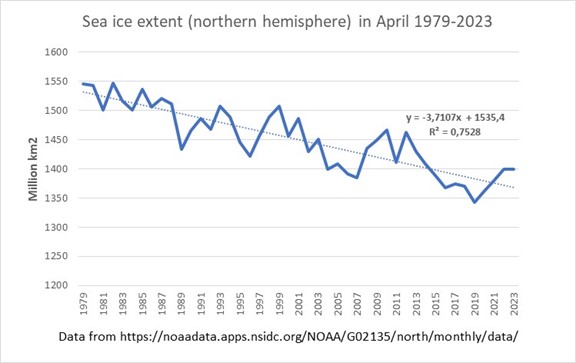

The persistence of the Arctic ringed seal, and other subspecies, will likely be challenged by the impacts of climate change, which are already apparent in the Arctic (e.g., Meier et al. 2004, Rosing-Asvid 2006, 2010, Kelly et al. 2010, Lydersen et al. 2007, 2010, 2014, Kovacs et al. 2008, 2012, Kovacs 2014). Habitat loss and deterioration caused by decreases in sea-ice and snow cover is expected to cause increases in pup mortality from premature weaning, hypothermia and predation.

Svalbard is one of the Arctic areas that has experience most warming so far, and one of the documented changes in ringed seal behaviour has been a stronger connection to glacier fronts (Hamilton et al. (2019a and 2019b). The diet is still focused on Arctic prey species (mainly polar cod) (Bengtsson et al. 2020) and the demography (age structure, reproductive parameters, body size and condition), seems to be unaffected so far (Andersen et al. 2021).

In the northernmost areas, one of the effects of warming is that multi-year ice will be replaced with annual ice and thereby form new ringed seal habitat. Productivity in the open water during summer will also increase productivity. Such changes are believed to have caused an increase in the Kane Basin polar bear population (Laidre et al. 2019). These kinds of changes might however be transient, and Kovacs (2014) stresses the importance of developing and implementing an Arctic ringed seal monitoring program, given the ecological and subsistence importance of this species in the Arctic.

Both the international programs CAFF (Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna) and AMAP (Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Program) under the Arctic Council have specifically requested that all of the Arctic countries launch scientific monitoring programs on ringed seal population structure, trends in abundance, vital rates and age structures, because of this species’ value as an ‘indicator species’ for monitoring global climate change and contaminant patterns. Today only Norway has a national program for ringed seal monitoring.

OKHOTSK, BALTIC, LAGODA AND SAIMAA RINGED SEALS

Commercial hunts in the Sea of Okhotsk and predator‐control hunts in the Baltic Sea, Lake Ladoga, and Lake Saimaa caused dramatic population declines in the past but have since been restricted.

The most recent population estimate for Okhotsk ringed seals (based on a survey from 2013) is about 120,000 animals (Chernook et al. 2014; Boveng 2016a). Earlier studies based on surveys from 1968–1990 indicated a population that was more than 5 times higher, but both the old and the new estimate have large uncertainties, and it cannot be stated with certain that the population have undergone a major decline (Chernook et al. 2014, Boveng 2016).

Unlike the habitat of the Arctic ringed seal the range of the Okhotsk population is bounded by land to the North so milder climate will not expand or improve the northernmost habitat.

The Baltic Sea population was likely increasing during 2003-2012 HELCOM (2023). After 2012, surveys have shown anomalously high estimates with significant variations between the years. This is potentially due to earlier ice breakup and lower ice coverage that have resulted in ringed seals hauling out in large groups and a larger portion of the total population being observed. The trend analysis for period after 2012 shows increases that are not biologically possible, so there are no trends available for this period (NMFS. (2024).

The Lake Ladoga population was estimated to exceed 5.000 seals in 2012 and may be recovering from steep declines caused by uncontrolled harvest in the past (BFN 2013).

The population of Saimaa seals was estimated to have been 160-180 in the 1980s but had increased to about 360 in 2016. By-catch is a significant source of mortality (Sipilä and Kokkonen 2008, Sipilä 2016), which adds to the consequences of reproductive failure in recent years due to poor ice conditions. Continued degradation of ice and snow habitat will likely further threaten the survival of this population.

STATUS ACCORDING TO OTHER INTERNATIONAL ORGANISATIONS

Ringed seals have no special conservation status under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Fauna and Flora (CITES) and are not listed in any appendix.

On the IUCN “Red list”, the ringed seal is listed as Least Concern in an assessment made in 2016. However, this assessment stipulates that “given the risks posed by climate change to all Ringed Seal subspecies, including the Arctic Ringed Seals, this species should be reassessed within a decade” (Kovacs et al. 2008).

The World Wildlife Fund (WWF) not only sees the Greenlandic Inuit hunt of seals, including ringed seals, as an important component of Greenland culture and economy, but considers the Inuit sealing to be sustainable and directly supports it. WWF (2013) calls for the EU to address the impacts of their import bans as well as to inform the European public about the Inuit exemption. It suggests that “with financial support from the EU, the existing certification label be considered expanded to guarantee e.g. sustainability of the hunt, full utilization of catches and animal welfare to meet increasing demands from conscious consumers in the EU as well as worldwide”.

In Canada, the ringed seal has been listed as “Not at Risk” by COSEWIC/COSEPAC in 1989 and has not been reviewed since.

Ringed seals are listed as “Vulnerable” in the Norwegian Red List (2021) and as “Least Concern” in the Greenlandic Red List (2018).

Management

Ringed seals inhabit the waters of two NAMMCO member states—Greenland and Norway. Only the Arctic ringed seal is present in these areas.

Humans have hunted ringed seals in the Arctic since the arrival of people to the region and they remain a fundamental subsistence resource for many northern coastal communities today (ACIA 2005, Hovelsrud et al. 2008, Kovacs et al. 2008, Kelly et al. 2008). Subsistence and commercial hunts of Arctic ringed seals have been large in the past, however there is no evidence to suggest that they have contributed to large‐scale population declines. Commercial hunts in the Sea of Okhotsk and predator‐control hunts in the Baltic Sea, Lake Ladoga, and Lake Saimaa caused population declines in the past but have since been restricted (Kelly et al. 2010).

No international governing body regulates the hunt of ringed seals. Advice on sustainable hunting and management of ringed seals is given by the North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO).

In most areas, there are relatively few restrictions on the hunting of ringed seals. In Canada, Greenland, Norway and Russia, a licence is required, but there are almost no restrictions on season or the number of animals that can be taken (Belikov & Boltunov 1998, Reeves et al. 1998, Teilmann & Kapel 1998). In Alaska, there are no limitations on the subsistence take of ringed seals. Total allowable catches (or TACs) are not set for ringed seals in Canada, but any commercial hunts are regulated by licenses and permits, and wastage is specifically prohibited.

In Norway, licensed hunters can shoot ringed seals in Svalbard from 20 May – 20 March. They are protected during their breeding season, as well as throughout the year in Svalbard national parks and nature reserves. Sport hunting of ringed seals is permitted on the Norwegian mainland. Individual hunters must have a licence and quotas on how many may be taken are set.

In Greenland there are no quotas or a fixed period of protection, but it is prohibited to hunt pups with lanugo hair and nursing females.

The general lack of catch quotas in most areas means that there has often been no requirement for hunters to register their catch. While records of commercial trade in sealskins exist for some areas, these likely represent a variable and sometimes small proportion of the number of seals that are actually taken. Hence historical catch records for ringed seals are in many cases poor and incomplete. Greenland has, however, been collecting complete catch statistics for all game species since 1992 and prior to that (1954-1983) was another system for collecting catch statistics – List-of-Game (Teilmann & Kapel 1998). Everyone engaged in hunting in Greenland must have a valid hunting license and in order to keep the license the hunter must submit a yearly catch report to the Ministry of Fisheries, Hunting and Agriculture.

UTILISATION

Ringed seals are the “daily bread” of many northern peoples. The Inuit in some parts of Greenland and Arctic Canada are heavily dependent on ringed seals for food, and on their skins for clothing and for sale. In some areas of the Arctic, the widespread and year-round existence of ringed seals is what has made the presence of human life possible.

Ringed seals, or “natseq”, can be hunted year-round, even during the dark months, and this has made them the most reliable source of daily necessities for the lives of northern peoples. Historically, ringed seals have provided a stable supply of meat and blubber for food, heating, and lighting, as well as skins for essential commodities such as boots (“kamiks”), clothing, tent coverings, bladder floats (“avataqs”) and other equipment essential for the survival and success of Inuit hunting communities.

Seal meat is also the essential “fuel” for the dogs that pull the sleds (Heide-Jørgensen & Lydersen 1998). Particularly in North and East Greenland, ringed seals remain a very important as a source of food for both humans and sled dogs (Rosing-Asvid 2010).

Catches in NAMMCO member countries since 1992

| Unexpected token "end of expression" of value "" around position 1. |

|---|

This database of reported catches is searchable, meaning you can filter the information by for instance country, species or area. It is also possible to sort it by the different columns, in ascending or descending order, by clicking the column you want to sort by and the associated arrows for the order. By default, 30 entries are shown, but this can be changed in the drop-down menu, where you can decide to show up to 100 entries per page.

Carry-over from previous years are included in the quota numbers, where applicable.

You can find the full catch database with all species here.

For any questions regarding the catch database, please contact the Secretariat at nammco-sec@nammco.no.

EU SEALSKIN BAN AND THE INUIT EXEMPTION

In 1983, the European Economic Community imposed an import ban on all whitecoat products (Kovacs 2015). The ban, which was initially for 2 years, has been extended since then and was expanded in 2009 to include juvenile (beater) pelts (Hammill et al. 2015).

Exceptions to the ban include products resulting from Inuit/Indigenous hunts, products for the sole purpose of sustainable management of marine resources, and products for the personal use of travellers to the EU. Furthermore, the ban does not apply to seal products trans-shipped through the EU to non-EU destinations (DFO 2016b).

In order for seal products to be exempt from the ban and placed on the market in the EU, the Inuit or Indigenous catch must meet certain conditions. The hunt must:

- be traditionally conducted by the community

- contribute to the community’s subsistence in order to provide food and income and not be primarily conducted for commercial reasons

- pay due care to animal welfare, while taking into account the community’s way of life and the subsistence purpose of the hunt (EUR-Lex 2016).

Other Human Impacts

Beyond hunting and direct utilisation, human activities can also impact ringed seal populations through climate change, pollution, habitat destruction and by-catch in commercial fisheries.

CLIMATE AND OCEANOGRAPHIC CHANGES

Climate change denotes changes in major weather patterns over a long time-scale and results from both natural variability and the influence of human activities. It is by far the most serious threat to Arctic biodiversity and exacerbates all other threats (CAFF 2013).

A potential long-term and alarming threat to ringed seals is human-induced global warming or climate change. Both the observed and the projected effects of a warming global climate are most extreme in northern high‐latitude regions (ACIA 2005, CAFF 2013). It has now become clear in the region that climate change is occurring, and that the Arctic has already undergone significant physical environmental changes due to global warming (ACIA 2005, CAFF 2013, Kovacs 2014 for review).

The observed and projected changes with significant potential to affect the ringed seal’s range and habitat (both its physical and biological components) are changes in sea ice, snow cover, ocean temperature, ocean pH (acidity), and associated changes in ringed seal predator and prey species.

Ringed seals are the most ice-associated/adapted pinnipeds in the Arctic and therefore the most vulnerable of the high-arctic pinnipeds. This is due to their reliance on sea ice as a platform for resting, whelping, nursing, and moulting, and their dependence on snow cover to provide protection from cold and predators and to successfully rear their young. Ice and snow cover are changing and will continue to do so as the climate warms. Numerous authors have studied and/or warned against the possible impact that global warming will have on ringed seals (Stirling et al. 1999, Stirling & Smith 2004, Meier et al. 2004, Ferguson et al. 2005, Stirling 2005, Rosing-Asvid 2006, 2010, Learmonth at al. 2006, Lydersen et al. 2007, 2010, 2014, Sipilä et al. 2007, Freitas et al. 2008b, Härkönen 2008, Kovacs & Lydersen 2008, Laidre et al. 2008, Moore & Huntington 2008, Kovacs et al. 2012).

The impacts of climate change on ringed seals and other Arctic species will be both direct and indirect and are reviewed in Kelly et al. (2010b) and Kovacs (2014). The impacts of climate change and the potential resilience of species are complex, but it is necessary to assess these factors so that suitable conservation actions can be taken (Moore & Huntington 2008).

A reduction in the extent and duration of ice cover would directly reduce the habitat available to ringed seals. It might also lead to poor condition of pups and higher pup mortality due to the early destruction of birth lairs. In the southern Baltic Sea, a series of nearly ice-free winters from 1989–1995 led to very high pup mortalities (Härkönen et al. 1998). Insufficient snow cover to protect pups in lairs in the spring will also likely lead to higher mortality due to increased predation. In warm years, ringed seal pups are more exposed to predation from polar bears due to a higher density of lairs on the smaller area of available sea ice and the fact that the lairs are weaker because there is less snow. The seals may also experience periods of thaw that can destroy their lairs and expose the pups (Hezel et al. 2012, Rosing-Asvid 2010). Ice is also needed by ringed seals for moulting, resting, and in some populations foraging, but the type of ice and its stability is not as important for the seals outside of the breeding season. Although northern ringed seals still exhibit a clear preference for areas with considerable ice coverage (e.g. Freitas et al., 2008).

Beyond the direct changes to their habitat, climate change will pose risks to ringed seals by inducing indirect changes. These include changes to their forage base (species and density shifts, and distributional shifts of prey species, etc.), increased competition from temperate species, increased predation rates from polar bears and arctic foxes (at least initially) as well as killer whales, increased disease and parasite risks, greater potential for exposure to increased pollution loads and impacts via increased human traffic and development in previously inaccessible, ice-covered areas (Kelly et al. 2010b, Kovacs 2014).

It is predicted that within the foreseeable future, the number of Arctic ringed seals will decline substantially, and they will no longer persist in a substantial portion of their range (Kelly et al. 2010). Kovacs (2014) stresses the importance of developing and implementing an Arctic ringed seal monitoring program, given the ecological and subsistence importance of this species in the Arctic. See under ‘‘Stock Status’ for more details.

There is some evidence of loss of habitats due to the loss of the sea ice, while in some other areas, e.g. some fjords in Greenland, there is gain of habitats. An example of this is in glacier fjords where retraction of the glacier makes the fjord longer and thereby increase the habitat. Another example is in high Arctic areas where multi-year ice (in which the ringed seals cannot make breathing holes) is replaced by annual sea ice where they can make and maintain breathing holes. (NAMMMCO, 2023).

Changes are indeed already taking place in the Arctic: see for example the figure below showing the sea ice extent in the northern hemisphere in April in the past five decades.

CONTAMINANTS

The levels of persistent organic pollutants (POPs), mercury, and radionuclides are particularly high in communities that have traditional dietary habits (e.g. Polder et al. 2003). This can be linked to the high contaminant loads in the marine mammals they consume.

Contaminant loads in ringed seals have been investigated in most parts of the species’ range, which reflects the ringed seal’s importance in the diets of coastal people and polar bears (Dietz et al. 1998, Hyvarinen et al. 1998, Muir et al. 1999, Bang et al. 2001, Fisk et al. 2002, 2005, Sonne et al. 2002, 2009, Rigét et al. 2005, 2006, Dietz 2008, Wolkers et al. 2008, Sonne et al. 2009, Routti et al. 2009, Kelly et al. 2010b, Kovacs 2014).

The Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP) was established in the 1990s to address the risks and trends in contaminants in the Arctic, and ringed seals were selected as a key monitoring species because of their broad circumpolar distribution, high abundance, high trophic status, and their frequency in the diet of coastal peoples (Wilson et al. 1998).

Pollutants such as organochlorine (OC) compounds and heavy metals have been found in all ringed seal populations, with males tending to have higher toxic loads than females for many substances. Relatively high levels of chlorinated hydrocarbons have been found in the blubber of ringed seals in some areas, probably as a result of atmospheric transport to the Arctic (Reeves 1998). OC contamination is also greater in the European Arctic than in the Canadian or U.S. Arctic (Borgå et al. 2005). In addition, metals including cadmium, mercury, zinc and selenium have been found to accumulate in other tissues (Dietz et al. 1998).

A risk assessment review of mercury exposure in ringed seals (and other Arctic species) found that ringed seals in most regions had no or low risk of Hg-mediated health effects. There were, however, some regions mainly in high Arctic Canada where a small fraction of the ringed seals had Hg concentrations in levels that potentially could cause health effects. (Dietz et al. 2022).

A suite of new-use chemicals previously unreported in the Arctic has been documented in arctic biota including ringed seals. However, little information exists for these compounds in terms of spatial patterns, food web dynamics, or species differences in levels (Kovacs 2014). Kovacs underlines that although levels of these compounds are currently low, there is concern because some are increasing rapidly in concentration in some areas (e.g., polybrominated diphenyl ethers, (Riget et al. 2006) and some have unique toxicological properties. Some of these compounds were presumed to have low potential for long-range transport and were therefore not expected to make their way into arctic biota. Kovacs (2014) also stresses that a better understanding of the effects of contaminants exposure is needed.

This is important because in addition to their direct toxicity, anthropogenic contaminants can increase susceptibility to disease and decrease resilience in marine mammals (Reijnders & de Ruiter-Dijkman 1995).

HABITAT DISTURBANCE AND ACOUSTIC POLLUTION

Reduction in sea ice cover due to global warming (see above) will likely lead to increased human activity in the Arctic in the form of shipping and resource extraction industries, with an associated increase in the threat of marine accidents, pollution discharge and human created noise.

Increased oil exploration, exploitation and possible oil spills, drilling and shipping are potential threats to ringed seals in some areas. Ice breakers may directly disrupt the ice habitat of ringed seals, although this would only affect a small area in relation to the total habitat available.

Noise from shipping and industrial activities may disturb ringed seals and disrupt their activities, possibly leading to the abandonment of prime habitat (Reeves 1998). To date, the rather isolated and inaccessible habitat of ringed seals had provided them some protection from these threats.

While some research has been done on sensitivity to noise pollution in Alaska show that ringed seals can adapt to noise as long as it is nor prolonged or long-term, monitoring changes in their behaviour or displacement due to the noise is not feasible. Unregulated icebreakers off the coast of Canada may cause disruption in mating and moulting season. Greenland has regulations in place due to other species (narwhal and beluga), but they protect ringed seals as well. Svalbard has implemented restrictions to using snowmobiles and icebreakers without a permit to reduce the disturbance, but there are other noise sources, such as tourism and fisheries.

Habitat disturbance, through manipulation of water levels, recreational snow machine operation, boating, tourism, shoreline construction, wind farms, etc., have been highlighted as specific threats for the Lakes Ladoga and Saimaa ringed seals (Sipilä & Hyvärinen 1998, Agafonova et al. 2007). Routine day-tourism seems to have caused the desertion of at least two previously used haul-out sites at Lake Ladoga (Agafonova et al. 2007, Verevkin et al. 2006). As many as 2,000 wind generators are planned to be erected in Bothnian Bay, the main breeding area for Baltic ringed seals, although the impacts on ringed seals from the disturbance associated with the construction and operation of wind farms are unknown.

BY-CATCH AND COMPETITION WITH FISHERIES

Arctic ringed seals have little interaction with commercial fisheries, both because they mainly consume non-commercial fish species, and because their distribution does not coincide with intensive fisheries in most areas. They are therefore seldom caught in fishing gear. However, capture in fishing gear and other negative impacts associated with fisheries is a major problem for the ringed seals in Lakes Saimaa and Ladoga (Sipilä & Hyvärinen 1998, Agafonova et al. 2007, Kovacs et al. 2012) and in the Baltic Sea (Härkonen et al. 1998). Young seals seem particularly susceptible to capture in nets.

GREENLAND

Research on ringed seal populations in Greenland has been ongoing for many years. Early research focused on monitoring the hunt (catch statistics, life history parameters, diet, contaminants). Some abundance surveys were also conducted, and movements were studied using conventional tagging. During recent years, ringed seals have been studied through tagging with satellite linked data-loggers.

Tagged Ringed seal © Aqqalu Rosing-Asvid

These tracking studies shows that some areas hold a high concentration of local stationary seals, whereas other areas are visited by migratory seals that swim long distances.

Tracking studies has shown that ringed seals in Kangia (Ilulissat Icefjord) are very local and that they kind of monopolise this fjord system. A genetic study show that these seals constitute a unique ecotype. See more under 2. General Characteristics /Subspecies and an ecotype.

Ringed seal studies in Greenland in near future focus on an aerial survey to update status of the Kangia ringed seals and more genetic studies to test the uniqueness of ringed seals that are stationary in other fjord systems

NORWAY

Ringed seals in Svalbard have been the subject of research efforts on a wide variety of topics intermittently since the early 1980s. Prominent in these research efforts has been the Norwegian Polar Institute (NPI), which has been looking at population parameters, diet, habitat use, reproductive and general ecology, reproductive energetics, abundance in different fjords, diving behaviour and physiology, and contaminant burdens. This body of research provides the basis for a data time series that will permit assessment of population and ecological trends.

In 2002, NPI began a dedicated monitoring programme for ringed seals as part of MOSJ (Monitoring of Svalbard and Jan Mayen), designed to explore important aspects of ringed seal population biology and ecology and provide the first comparative data in a time series for the population (Kovacs & Lydersen 2006). This work focuses on density and abundance of ringed seals in selected fjords, trends in population parameters (age structure and vital rates), diet, genetics, condition and ‘health status’ (blubber-reserves, serum chemistry, parasite infestations), and contaminant burdens (POPs, heavy metals, toxaphenes).

The project ICE Ecosystems is a research programme that focuses on Arctic species that are dependent on ice during some part of their life cycles and are threatened by future climate change: ice fauna, zooplankton, polar cod, polar bears, ringed seals, and ivory gulls. As part of the ICE ringed seal programme from 2010 to 2012, 38 ringed seals off Svalbard were instrumented with advanced satellite tags to get information on the life of the seals and their use of the sea ice outside the breeding and moulting periods. In 2013, tagging continued using various combinations of satellite tags and sensors that were deployed on males and females of different age classes.

The satellite tags used in this research programme provided standard information on where the seals were, how deep they were diving and for how long. They also provided hydrographic data (salinity and temperature) as well as information providing insights into primary production (chlorophyll levels) in the regions where the seals swim and dive. Ringed seals are a of part of Kongsjfjorden Case Study (ARK) together with bearded and harbour seals. The animals are equipped with biologging instrument to study space use and potential competition in the fjord where it seems that more temperate species like harbour seals, are taking over the area from more arctic species such as ringed and bearded seals. SMRU tags are used to record and transmit a GPS position every time a seal is at the surface, as well as to transmit data from every dive, which provide a spatial and temporal resolution of the data that is necessary for this study (NPR, 2023).

Sea ice has continued to decline markedly within the archipelago in recent years, with no sea ice formation at all taking place in most of Svalbard’s fjords in the winter of 2011 and spring of 2012. Instrumented animals tracked via ARGOs and GPS systems will document their responses to these unique conditions, which are likely precursors of what ringed seals will experience elsewhere in the decades to come (Lydersen & Kovacs, in Kovacs 2014).

Fitting a satellite tag to a ringed seal back at Svalbard. Scientists K. M. Kovacs and C. Hamilton (NPI) sitting over a ringed seal while gluing a satellite tag to its fur (left) prior to its release (right). © K.M. Kovacs and C. Lydersen, Norwegian Polar Institute, from ICE Ringed seals – 2nd field report.

Ringed seals in all ice-covered areas in Isfjorden, Svalbard, were surveyed with drones in May/June for hauled-out seals as a part of new time series to monitor ringed seal population trends in selected fjords in the archipelago. In addition, in 2020, 25 ringed seals were collected from the Isfjorden area in Svalbard by researchers from NPI and data on morphometrics, age, sex and various tissues were delivered to the Norwegian Environmental Specimen Bank (National Progress Report Norway 2023).

Andersen, M., Kovacs, K. M., & Lydersen, C. (2021). Stable ringed seal (Pusa hispida) demography despite significant habitat change in Svalbard, Norway. Polar Research, 40. https://doi.org/10.33265/polar.v40.5391

Arctic Climate Impact Assessment (ACIA). (2005). Cambridge, UK, Cambridge University Press. 1042 pp. Available at http://www.acia.uaf.edu./pages/scientific.html

Agafonova, E.V., Verevkin, M.V., Sagitov, R.A., Sipilä, T., Sokolovskay, M.V. and Shahnazarova, V.U. (2007). The ringed seal in Lake Ladoga and the Valaam Archipelago. Baltic Fund for Nature of Saint- Petersburg Naturalist Society, St. Petersburg State University & Metsähallitus, Natural Heritage Servives, Vammalan Kirjapaino OY., Vammala, Finland.

Andersen, S.M., Lydersen, C., Grahl-Nielsen, O. and Kovacs, K.M. (2004). Autumn diet of harbour seals (Phoca vitulina) at Prins Karls Forland, Svalbard, assessed via scat and fatty-acid analyses. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 82(8), 1230–1245. https://doi.org/10.1139/z04-093

Bang, K., Jenssen, B.M., Lydersen, C. and Skaare, J.U. (2001). Organochlorine burdens in blood of ringed and bearded seals from north‐western Svalbard.Chemosphere, 44(2), 193–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0045-6535(00)00197-1

Belikov, S.E. and Boltunov, A.N. (1998). The ringed seal (Phoca hispida) in the western Russian Arctic. NAMMCO Scientific Publications, 1, 63–82. https://doi.org/10.7557/3.2981

Bengtson, J.L., Hiruki-Raring, L.M., Simpkins, M.A. and Boveng, P.L. (2005). Ringed and bearded seal densities in the eastern Chukchi Sea, 1999-2000. Polar Biology, 28, 833–845. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00300-005-0009-1

Biologists for Nature Conservation. (2013). Final report on the implementation of the project “Assessment of ringed seal bycatch in commercial fisheries and its impact on seal population in Lake Ladoga, Northwest Russia.”

Bonner, N. (1994). Seals and sea lions of the world. London: Blandford, 224 pp.

Borgå, K., Gabrielsen, G.W., Skaare, J.U., Kleivane, L., Norstrom, R.J. and Fisk, A.T. (2005). Why do organochlorine differences between arctic regions vary among trophic levels? Environmental Science and Technology, 39(12), 4343‐4352. https://doi.org/10.1021/es0481124

Born, E.W., Teilmann, J. and Riget, F. (2002). Haul-out activity of ringed seals (Phoca hispida) determined from satellite telemetry. Marine Mammal Science, 18(1), 167–181. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-7692.2002.tb01026.x

Born, E.W., Teilmann, J., Acquarone, M. and Riget, F.F. (2004). Habitat Use of Ringed Seals (Phoca hispida) in the North Water Area (North Baffin Bay). Arctic, 57(2), 129–142. https://doi.org/10.14430/arctic490

Boveng, P. (2016a). Pusa hispida ssp. ochotensis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T41677A66991702. https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T41677A66991702.en

Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna (CAFF). (2013). Arctic Biodiversity Assessment. Status and trends in Arctic biodiversity. Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna, Akureyri. Available at http://www.caff.is/publications/view_category/10-arctic-biodiversity-assessment

Carlens, H., Lydersen, C., Krafft, B.A., and Kovacs, K.M. (2006). Spring haul-out behavior of ringed seals (Pusa hispida) in Kongsfjorden, Svalbard. Marine Mammal Science, 22(2), 379–393. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-7692.2006.00034.x

Chernook, Vladimir & Grachev, Aleksey & Vasiliev, Alexandr & Trukhanova, Irina & Burkanov, Vladimir & Solovyev, Boris. (2014). Results of instrumental aerial survey of ice-associated seals on the ice in the Okhotsk Sea in May 2013. TINRO News. Vol. 179.. P. 158–176.. https://doi.org/10.26428/1606-9919-2014-179-158-176.

Dehn, L.‐A., Sheffield, G., Follmann,E., Duffy, L., Thomas, D. and O’Hara, T. (2007). Feeding ecology of phocid seals and some walrus in the Alaskan and Canadian Arctic as determined by stomach contents and stable isotope analysis. Polar Biology, 30, 167–181. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00300-006-0171-0

Dietz, R. (2008). Contaminants in marine mammals in Greenland — with linkages to trophic levels, effects, diseases and distribution. DSc Thesis. University of Aarhus, Denmark, Copenhagen, Denmark. 120 p. Available at https://www2.dmu.dk/Pub/Doctor_RDI.PDF

Dietz, R., Letcher, R. J., Aars, J., Andersen, M., Boltunov, A., Born, E. W., Ciesielski, T. M., Das, K., Dastnai, S., Derocher, A. E., Desforges, J.-P., Eulaers, I., Ferguson, S., Hallanger, I. G., Heide-Jørgensen, M. P., Heimbürger-Boavida, L.-E., Hoekstra, P. F., Jenssen, B. M., Kohler, S. G., … Sonne, C. (2022). A risk assessment review of mercury exposure in Arctic marine and terrestrial mammals. Science of The Total Environment, 829, 154445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.154445

Dietz, R., Paludan-Müller, P., Agger, C.T. and Nielsen, C.O. (1998). Cadmium, mercury, zinc and selenium in ringed seals (Phoca hispida) from Greenland and Svalbard. NAMMCO Scientific Publications, 1, 242–273. https://doi.org/10.7557/3.2992

Fedoseev, G.A. (2000). Population biology of ice‐associated forms of seals and their role in the northern Pacific ecosystems. Center for Russian Environmental Policy, Russian Marine Mammal Council, Moscow, Russia. 271 p. (Translated from Russian by I. E. Sidorova).

Ferguson, S., and Secretariat, C.S.A. (2009). Review of aerial survey estimates for ringed seals (Phoca hispida) in western Hudson Bay. DFO Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat, Science Advisory Report 2009/004. Available at http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/csas-sccs/Publications/SAR-AS/2009/2009_004-eng.htm

Ferguson, S.H., Stirling, I. and Mcloughlin, P.M. (2005). Climate change and ringed seal (Phoca hispida) recruitment in western Hudson Bay. Marine Mammal Science, 21(1), 121–135. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-7692.2005.tb01212.x

Ferguson, S. H., Zhu, X., Young, B. G., Yurkowski, D. J., Thiemann, G. W., Fisk, A. T., & Muir, D. C. G. (2018). Geographic variation in ringed seal (Pusa hispida) growth rate and body size. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 96(7), 649–659. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjz-2017-0213

Finley, K. J., Miller, G. W., Davis, R.A. and Koski, W.R. (1983). A distinctive large breeding population of ringed seals (Phoca hispida) inhabiting the Baffin Bay pack ice. Arctic, 36(2), 162–173. https://doi.org/10.14430/arctic2259

Fisk, A.T., de Wit, C.A., Wayland, M., Kuzyk, Z.Z., … and Muir, D.C.G. (2005). An assessment of the toxicological significance of anthropogenic contaminants in Canadian arctic wildlife. Science of the Total Environment, 351–352, 57‐93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2005.01.051

Fisk, A.T., Holst, M., Hobson, A., Duffe, J., Moisey, J. and Norstrom, R.J. (2002). Persistent organochlorine contaminants and enantiomeric signatures of chiral pollutants in ringed seals (Phoca hispida) collected on the east and west side of the Northwater polynya, Canadian Arctic. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 42, 118‐126. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002440010299

Freitas, C., Kovacs, K.M., Fedak, M.A. and Lydersen, C. (2008a). Ringed seal post-moulting movement tactics and habitat selection. Oecologia, 155(1), 193–204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-007-0894-9

Freitas, C., Kovacs, K.M. and Lydersen, C. (2008b). Predicting habitat use by ringed seals (Phoca hispida) in a warming Arctic. Ecological Modelling, 217(1–2), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2008.05.014

Frost, K.J., Lowry, L.F., Pendleton, G. and Nute, H.R. (2004). Factors affecting the observed densities of ringed seals, Phoca hispida, in the Alaskan Beaufort Sea, 1996–1999. Arctic, 57(2), 115–128. https://doi.org/10.14430/arctic489

Furgal, C.M., Innes, S. and Kovacs, K.M. (2002). Inuit spring hunting techniques and local knowledge of the ringed seal in Arctic Bay (Ikpiarjuk), Nunavut. Polar Research, 21(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3402/polar.v21i1.6470

Gjertz, I., Kovacs, K. M., Lydersen, C. and Wiig, Ø. (2000). Movements and diving of adult ringed seals (Phoca hispida) in Svalbard. Polar Biology, 23, 651–656. https://doi.org/10.1007/s003000000143

Government of Greenland. (2012). Ministry of Fisheries, Hunting and Agriculture. Management and utilization of seals in Greenland. 39pp.

Hammill, M.O. and Smith, T.G. (1990). Application of removal sampling to estimate the density of ringed seals (Phoca hispida) in Barrow Strait, Northwest Territories. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 47(2), 244–250. https://doi.org/10.1139/f90-027

Hamilton, C.D., Kovacs, K.M., & Lydersen, C. (2019). Sympatric seals use different habitats in an Arctic glacial fjord. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 615, 205–220. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps12917

Hamilton, C. D., Vacquié-Garcia, J., Kovacs, K. M., Ims, R. A., Kohler, J., & Lydersen, C. (2019). Contrasting changes in space use induced by climate change in two Arctic marine mammal species. Biology Letters, 15(3), 20180834. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2018.0834

Harding, K.C. and Härkönen, T.J. (1999). Development of the Baltic grey seal (Halichoerus grypus) and ringed seal (Phoca hispida) populations during the 20th century. Ambio, 28(7), 619–627. Available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/279587941

Härkönen, T. (2008). Vikaresälen pressad av mildare klimat. Havet 2008, 89–90. Available at http://www.havet.nu/dokument/havet2008-vikaresal.pdf [In Swedish]

Harkonen, T., Jüssi, M., Jüssi, I., Verevkin, M., Dmitrieva, L., Helle, E., Sagitov, R. and Harding, K.C. (2008). Seasonal activity budget of adult Baltic ringed seals. PLoS ONE, 3, e2006. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0002006

Härkönen, T., Stenman, O., Jüssi, M., Jüssi, I., Sagitov, R. and Verevkin, M. (1998). Population size and distribution of the Baltic ringed seal (Phoca hispida botnica). NAMMCO Scientific Publications, 1, 167–180. https://doi.org/10.7557/3.2986

Heide‐Jørgensen, M.P. and Lydersen, C. (1998). Ringed Seals in the North Atlantic. NAMMCO Scientific Publications, 1, 5–8. https://doi.org/10.7557/3.2978

Heino, M. T., Nyman, T., Palo, J. U., Harmoinen, J., Valtonen, M., Pilot, M., & Aspi, J. (2023). Museum specimens of a landlocked pinniped reveal recent loss of genetic diversity and unexpected population connections. Ecology and Evolution, 13(1), Article 9720. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.9720

Hezel , P. J., Zhang, X., Bitz, C. M., Kelly, B. P., and Massonnet, F. (2012). Projected decline in spring snow depth on Arctic sea ice caused by progressively later autumn open ocean freeze-up this century. Geophysical Research Letters, 39(17), L17505. https://doi.org/10.1029/2012GL052794

HELCOM. (2023). Population trends and abundance of seals: Helsinki Commission (HELCOM) core indicator report. Helsinki, Finland. https://indicators.helcom.fi/indicator/ringed-seal-abundance/

Holst, M., Stirling, I. and Hobson, K.A. (2001). Diet of ringed seals (Phoca hispida) on the east and west sides of the North Water Polynya, northern Baffin Bay. Marine Mammal Science, 17(4), 888–908. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-7692.2001.tb01304.x

Hovelsrud, G.K., McKenna, M. and Huntington, H.P. (2008). Marine mammal harvests and other interactions with humans. Ecological Applications, 18(sp 2), 135‐147. https://doi.org/10.1890/06-0843.1

Hyvärinen, H., Sipilä, T., Kunnasranta, M. and Koskela, J.T. (1998). Mercury pollution and the Saimaa ringed seal (Phoca hispida saimensis). Marine Pollution Bulletin, 36(1), 76‐81. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0025-326X(98)90037-6

Iversen, M., Aars, J., Haug, T., Alsos, I.G., Lydersen, C., Bachmann, L. and Kovacs, K.M. (2013). The diet of polar bears (Ursus maritimus) from Svalbard, Norway, inferred from scat analysis. Polar Biology, 36(4), 561–571. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00300-012-1284-2

Jeffries, M.O., Richter-Menge, J.A. and Overland, J.E. (eds.). (2013). Arctic Report Card 2013. Available at https://www.arctic.noaa.gov/Report-Card

Johanessen, O.M., Miles, M.W. and Bjørgo, E. (1995). The Arctic’s shrinking sea ice. Nature, 376, 126-27. https://doi.org/10.1038/376126a0

Johansen, C.E., Lydersen, C., Aspholm, P.E., Haug, T. and Kovacs, K.M. (2010). Helminth parasites in ringed seals (Pusa hispida) from Svalbard, Norway with special emphasis on nematodes: Variation with age, sex, diet, and location of host. Journal of Parasitology, 96(5), 946–953. https://doi.org/10.1645/GE-1685.1

Kapel, F.O., Christiansen, J., Heide-Jørgensen, M.P., Härkönen, T., Born, E.W., Knutsen, L.Ø., Riget, F. and Teilmann, J. (1998). Netting and conventional tagging used to study movements of ringed seals (Phoca hispida) in Greenland. NAMMCO Scientific Publications, 1, 211–228. https://doi.org/10.7557/3.2990

Karlsson, O., Härkönen, T. and Bäcklin, B.-M. (2007). Seals on the increase [In Swedish – Sälar på uppgång]. Havet 2007, 84–89. Available at http://www.havet.nu/dokument/Havet2007-salar.pdf

Kelly, B. P., Badajos, O.H., Kunnasranta, M. and Moran, J. (2006). Timing and re‐interpretation of ringed seal surveys. Coastal Marine Institute University of Alaska Fairbanks, Final Report. 60 p. Available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/292158758

Kelly, B. P., Badajos, O.H., Kunnasranta, M. and Moran, J., Martinez-Bakker, M., Wartzok, D. and Boveng, P. (2010a). Seasonal home ranges and fidelity to breeding sites among ringed seals. Polar Biology, 33, 1095–1109. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00300-010-0796-x

Kelly, B.P., Bengtson, J.L., Boveng, P.L., Cameron, M.F., Dahle, S.P., Jansen, J.K., Logerwell, E.A., Overland, J.E., Sabine, C.l., Waring, G.T. and Wilder, J. M. (2010b). Status Review of the ringed seal (Phoca hispida). U.S. Dep. Commer., NOAA Tech. Memo. NMFS-AFSC-212. 250pp. Available at http://www.afsc.noaa.gov/Publications/AFSC-TM/NOAA-TM-AFSC-212.pdf

Kelly, B.P. and Quakenbush, L.T. (1990). Spatiotemporal use of lairs by ringed seals (Phoca hispida). Canadian Journal of Zoology, 68(12), 2503–2512. https://doi.org/10.1139/z90-350

Kingsley, M.C.S. (1998). The number of ringed seals (Phoca hispida) in Baffin Bay and associated waters. NAMMCO Scientific Publications, 1, 181–196. https://doi.org/10.7557/3.2988

Kingsley, M.C.S. (1990). The status of the ringed seal, Phoca hispida, in Canada. Prepared for the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Cananda. Canadian Field-Naturalist, 104, 138–145.

Kingsley, M.C.S. and Byers, T. (1998). Failure of reproduction in ringed seals (Phoca hispida) in Amundsen Gulf, Northwest Territories in 1984-1987. NAMMCO Scientific Publications, 1, 197–210. https://doi.org/10.7557/3.2989

Kostamo, A., Hyvärinen, H., Pellinen, J. and Kukkonen, J.V.K. (2002). Organochlorine concentrations in the Saimaa ringed seal (Phoca hispida saimensis) from Lake Haukivesi, Finland, 1981-2000. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 21(77), 1368–1376. https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.5620210706

Kovacs, K.M. (ed.). (2014). Circumpolar ringed seal (Pusa hispida) monitoring. Norwegian Polar Institute, Report Series 143. 45pp. Available at Rapport143.pdf (npolar.no)

Kovacs, K.M., Aguilar, A., Aurioles, D., Burkanov, V., … and Trillmich, F. (2012). Global threats to pinnipeds. Marine Mammal Science, 28(2), 414–436. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-7692.2011.00479.x

Kovacs, K.M., Belikov, S., Boveng, P., Desportes, G., Ferguson, S., Hansen, R., Laidre, K., Stenson, G., Thomas, P., Ugarte, F., Vongraven, D., & Martínez Llobet, S. (2021). State of the Arctic marine biodiversity report update: Marine mammals.

Kovacs K. M., Citta J., Brown T., Dietz R., Ferguson S., Harwood L., Houde M., Lea E. V., Quakenbush L., Riget F., Rosing-Asvid A., Smith T., Svetochev V., Svetocheva O., & Lydersen C. (2021). Variation in body size of ringed seals (Pusa hispida hispida) across the circumpolar Arctic: evidence of morphs, ecotypes or simply extreme plasticity?. Polar Research, 40. https://doi.org/10.33265/polar.v40.5753

Kovacs, K.M., Lowry, L. and Härkönen, T. (IUCN SSC Pinniped Specialist Group). (2008). Pusa hispida. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2014.2. Available at http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/full/41672/0

Kovacs, K.M. and Lydersen, C. (2006). Population biology of ringed seals in Svalbard, Norway. Polar Research in Tromsø, 3–4.

Kovacs, K.M. and Lydersen, C. (2008). Climate change impacts on seals and whales in the North Atlantic Arctic and adjacent shelf seas. Science Progress, 91(2), 117–150. https://doi.org/10.3184/003685008X324010

Krafft, B.A., Kovacs, K.M., Andersen, M., Aars, J., Lydersen, C., Ergon, T. and Haug, T. (2006a). Abundance of ringed seals (Pusa hispida) in the fjords of Spitsbergen, Svalbard, during the peak molting period. Marine Mammal Science, 22(2), 394–412. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-7692.2006.00035.x

Krafft, B. A., Kovacs, K. M., Frie, A. K., Haug, T. and Lydersen, C. (2006b). Growth and population parameters of ringed seals (Pusa hispida) from Svalbard, Norway, 2002–2004. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 63(6), 1136–1144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icesjms.2006.04.001

Krafft, B.A., Kovacs, K.M. and Lydersen, C. (2007). Distribution of sex and age groups of ringed seals Pusa hispida in the fast-ice breeding habitat of Kongsfjorden, Svalbard. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 335, 199–206. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps335199

Krupnik, I., Aporta, C., Gearheard, S., Laidler, G.J. and Kielsen Holm, L. (eds.). (2010). SIKU: Knowing Our Ice: Documenting Inuit Sea Ice Knowledge and Use. Springer Science and Business Media. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-8587-0

Labansen, A.L., Lydersen, C., Haug, T., and Kovacs, K.M. (2007). Spring diet of ringed seals (Phoca hispida) from northwestern Spitsbergen, Norway. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 64(6), 1246–1256. https://doi.org/10.1093/icesjms/fsm090

Labansen, A.L., Lydersen, C., Levermann, N., Haug, T. and Kovacs, K.M. (2011). Diet of ringed seals (Pusa hispida) from Northeast Greenland. Polar Biology, 34(2), 227–234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00300-010-0874-0

Laidre, K., Atkinson, S., Regehr, E., Stern, H., Born, E., Wiig, Ø., Lunn, N., Dyck, M., Heagerty, P., & Cohen, B. (2020). Transient benefits of climate change for a high-Arctic polar bear (Ursus maritimus) subpopulation. Global Change Biology, 26. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.15286

Laidre, K. L., Stern, H., Kovacs, K. M., Lowry, L., Moore, S. E., Regehr, E. V., Ferguson, S. H., Wiig, Ø., Boveng, P., Angliss, R. P., Born, E. W., Litovka, D., Quakenbush, L., Lydersen, C., Vongraven, D., & Ugarte, F. (2015). Arctic marine mammal population status, sea ice habitat loss, and conservation recommendations for the 21st century. Conservation Biology, 29(3), 724–737. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12474

Laidre, K.L., Stirling, I., Lowry, L.F., Wiig, Ø., Heide-Jørgensen, M.P. and Ferguson, S.H. (2008). Quantifying the sensitivity of Arctic marine mammals to climate-induced habitat change. Ecological Applications, 18(sp 2), 97–125. https://doi.org/10.1890/06-0546.1