Bowhead whale

Updated: April, 2024 (reviewed by the Scientific Committee)

The bowhead whale is a large baleen whale. With a body mass of up to 100 tonnes and a length of up to 20 m, the bowhead whale is one of the largest animals on the planet. Females are slightly larger than males. The bowhead whale has no dorsal fin unlike most other baleen whales. The disproportionally large head constitutes more than one-third of the entire length of the animal. The name bowhead is associated with the whale’s high, arched lower jaw that looks like an archer’s bow.

Bowhead whales are predominately black but with much of their chin and lower jaw being white. A row of pigmented spots is also located on each side of the lower jaw. A light grey or whitish band around the peduncle in front of the fluke is seen in some (older) whales. The bowhead whale is the longest-living mammal on the planet and can reach an impressive age of more than 200 years.

ABUNDANCE

In 2016, total abundance of the North Atlantic bowhead whale population was estimated as being nearly 8,000 animals, mainly in the East Canada–West Greenland stock.

DISTRIBUTION

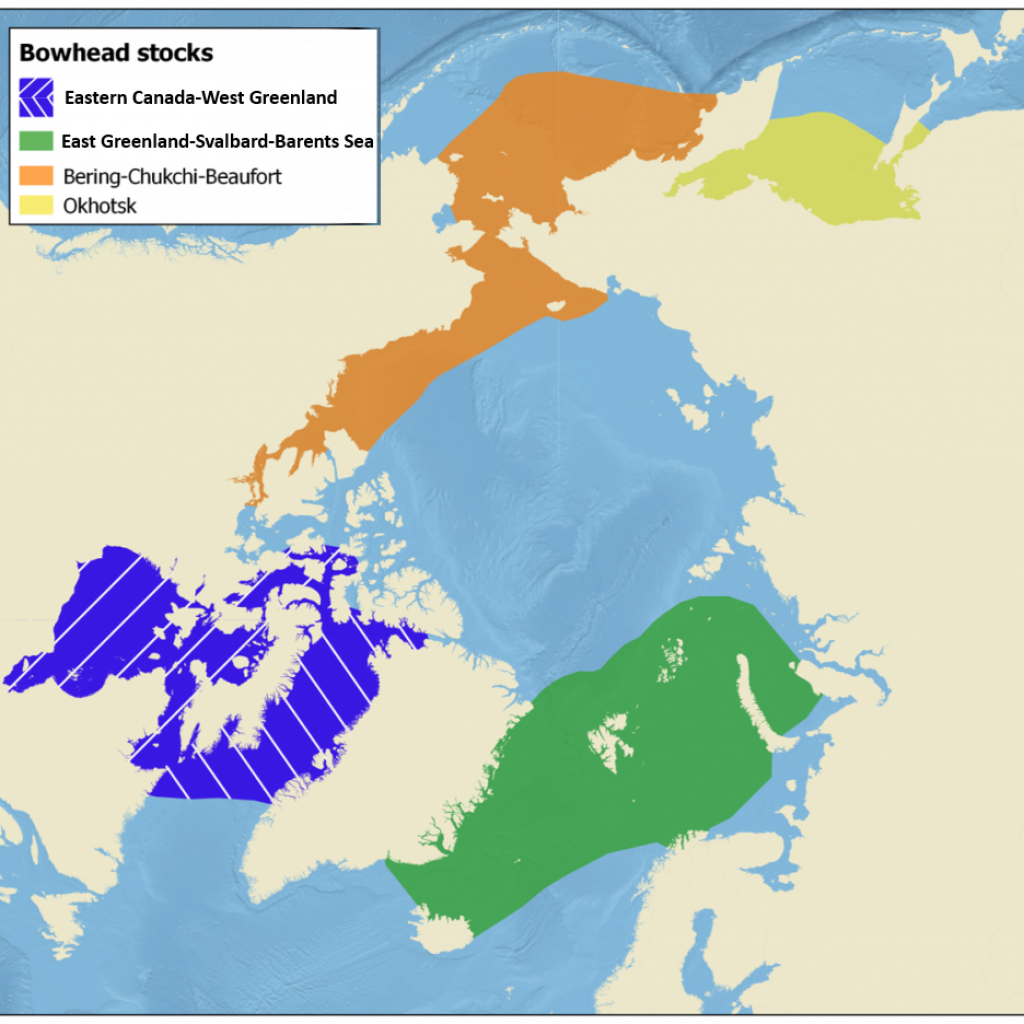

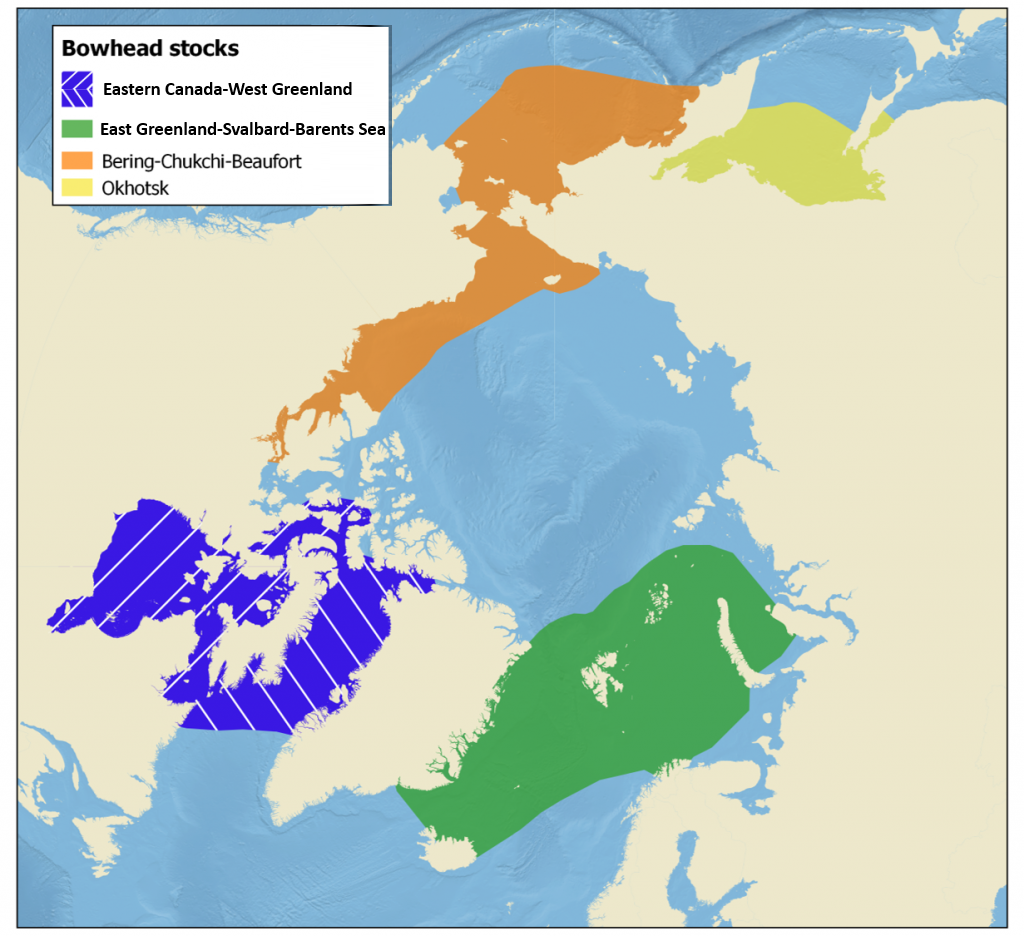

Bowhead whales can be found in the circumpolar Arctic and sub-Arctic waters, both in northern Atlantic and Pacific waters. Two stocks inhabit the North Atlantic—one in Eastern Canada–West Greenland (ECWG), and one in the East Greenland–Svalbard–Barents Sea (EGSB) area.

RELATION TO HUMANS

Bowhead whales have historically been hunted by native people. There has also previously been a large commercial hunt, which decimated the populations. Currently in the North Atlantic, few bowhead whales are taken by Inuit in Canada and Greenland.

CONSERVATION AND MANAGEMENT

Populations were reduced by historical whaling, but the ECWG stock is increasing, and new evidence shows possible increases in the EGSB stock as well. In Canada, hunting is managed by Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO). Greenland gets an annual quota of two individuals from the International Whaling Committee (IWC) and provides specific regulations. The EGSB stock is protected from hunting.

On the IUCN Red List, the most recent assessments (2023), list bowhead whales as ‘Vulnerable’ on a regional scale for Europe. The species is listed as ‘Endangered’ on Norwegian national red list, and according to the Greenlandic national red list, ECWG stock is ‘Near threatened’ and EGSB stock is ‘Vulnerable’.

Bowhead whale in Svalbard ©Nick Cobbing

Scientific name: Balaena mysticetus (Linnaeus 1758)

Faroese: Grønlandsslættibøka

Greenlandic: Arfivik

Icelandic: Grænland hvalur

Norwegian: Grønlandshval

Danish: Grønlandshval

English: Bowhead whale, Greenland right whale or Arctic whale

Average Size

Bowheads whales’ average length is approximately 18 m long (although they can reach a length of 20 m). They have a body mass of 70-100 tonnes. Females are larger than males

Lifespan

Bowhead whales live up to ~200 years.

Feeding

Bowhead whales are filter feeders. They feed by swimming slowly forward with their mouth wide open. Their diet consists of zooplankton, mainly copepods

Productivity

Female bowhead whales have one calf every 3-4 years from a body length of 13-13.5 m at around 25 years of age.

Migration

The bowhead whale is an Arctic resident, living its whole life in Arctic or sub-Arctic waters. It is migratory, with a seasonal appearance in certain areas and this migration is generally influenced by the distribution of sea ice.

General Characteristics

The bowhead whale belongs to the family Balaenidae and genus Balaena.

The bowhead whale is thick-bodied compared to other baleen whales. The head constitutes one third of the body length and they have the longest baleen plates of all whales. The skin is smooth, the back broad and there is no dorsal fin or dorsal hump. The paired blowholes are located on a distinct elevation called the crown. The eyes are located quite low on the sides of the head. Flippers are short and broad.

Colouration is predominately black with the chin and lower jaw being white. A row of pigmented spots is located on each side of the lower jaw. In some (older) whales a light grey or whitish band around the peduncle in front of the fluke is seen. The amount of white on the fluke and tail increases with age. Older individuals can be whiter on the head and can be heavily scarred (Reeves & Leatherwood 1985). The blubber layer of the bowhead whale is thick, ranging from 5.5 cm on the chin to 28 cm on the trunk (Haldiman & Tarpley ).

Bowhead whale fluke in Disko Bay, Greenland. © Camilla Ilmoni.

Size

Females are typically larger than males. Adult bowhead whales measure 12–18 m in length with some individuals reaching lengths of ~20 m (Haldiman & Tarpley 1993). These whales weigh about 80 metric tons, with some individuals weighing over 100 metric tons (George et al. 2018). The flippers are short and broad and fluke width averages 33% of body length (Haldiman & Tarpley 1993).

Behaviour

Bowhead whales are relatively slow swimmers. Their migratory speed has been reported at approximately 1.1–2.5 m/s, which is within the same range as the mean speed for other baleen whales when foraging at the surface (Simon et al. 2009, Heide-Jørgensen et al. 2006). Tracking of bowhead whales with satellite transmitters in West Greenland in winter has shown that these whales can travel fast through dense pack ice. Three whales (one male and two females) were shown to travel 1,730–5,888 kilometres in one month. The authors hypothesised that bowhead whales have the potential to cross stock boundaries that were perhaps not anticipated when the boundaries were established (Heide-Jørgensen et al. 2006).

Feeding behaviour

© Olga Shpak

The large head of the bowhead whale, which comprises approximately one-third of its total body length, functions as an enormous feeding device. The impressive mouth gap is more than 4 m2. The mouth forms a gigantic filtering apparatus with baleen plates up to 4 m long (Simon et al. 2009).

When foraging, bowhead whales move at very slow speeds, less than 1 m/s. Each foraging dive can amount to ~2000 tons of filtered water and prey. Bowhead whales are not deep divers. Simon et al. (2006) showed a maximum foraging dive depth of 127 m and a mean dive time of 11–20 min per dive. Bowhead whales have also been observed to drift-dive, meaning that for a proportion of the dive they do not move and are suspended in the water column while drifting up- or downwards to rest or sleep (Blackwell et al., 2022). The bowhead whale diet consists mainly of zooplankton, especially calanoid copepods and amphipods as well as other small crustaceans.

Sounds and Communication

Bowhead whales are highly vocal. They use sounds for communication, socializing, foraging, navigation, and mate selection. Five species of baleen whales are known to produce songs: the bowhead whale, blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus), humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae), fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus) and minke whale (Balaenoptera acutorostrata). Bowhead whale singing is most intense in the breeding season, but they have also been reported singing in other seasons (Reese et al. 2001, Würsig & Clark 1993).

Stafford et al. (2012) found bowhead whales in Fram Strait (between Greenland and Svalbard) to call or sing continuously from November through April. From the same area Ahonen et al. (2017) detected signals of bowhead whales almost daily from October through until April with significantly fewer detections in the period May–July. More than 60 unique songs were recorded. Stafford et al. (2018) found that members of the EGSB stock produced 184 different song types over a 3-year period from a site in Fram Strait. Distinct song types were recorded over short periods, lasting at most some months. Also, Johnson et al. (2014) found great variability in songs for bowhead whales from the Bering-Chukchi-Beaufort stock and that songs were shared among individuals.

Social and sexual behaviour

Bowhead whales are often segregated by size, sex, and reproductive state during migration and in their summering grounds. Population segregation may be related to predation pressures, diving abilities and habitat partitioning (Finley 2001). There are different reports regarding bowhead whale social organisation relating to populations, sex of the animal, age, and whether females are traveling with a calf. Bowhead whales have been observed in great numbers, for example in areas with plenty of food or when traveling between sites. However, whether or not they are gregarious animals as such is still an open question. Large aggregations of up to 20–60 animals have been observed along the east coast of Baffin Island and in the Beaufort Sea. During migration, bowhead whales often travel alone, in pairs, or in small groups (Reeves & Leatherwood 1985).

Sexual interaction between bowhead whales has been observed during the spring migration in the western Arctic but has also been observed in the autumn for animals of the Bering Sea stock. For the ECWG stock, sexual behaviour has been reported in the fall at Isabella Bay, Northeast Canada. Sexual activity can take place between pairs of whales but most often occurs in larger ’mating’ groups (Würsig & Clark 1993).

Bowhead whale © Fernando Ugarte

AT SEA

The bowhead whale is one of the stockiest whales of appearance. Compared to the fast fin whale, for example, the bowhead whale is a relatively slow swimmer. When swimming, only the whale’s head and the rounded back are above the water surface.

The bowhead whale has many structural similarities with genus Eubalaena (right whales). Two obvious characteristics distinguish them from each other; the bowhead whale’s higher arch of the upper jaw and the absence of bonnet callosities (bumps of hardened skin on the top of the rostrum) (Haldiman & Tarpley 1993).

Bowhead whales often occupy polynyas during winter but can move easily through extensive areas of nearly solid sea ice and break through ice up to 45 cm thick (Kovacs et al., 2011).

The bowhead whales two blowholes send a V-shaped blow several meters in the air when expelling air from them.

Bowhead whale in Disko Bay, Greenland, sending out a V-shaped blow. © Mads Peter Heide-Jørgensen.

DID YOU KNOW?

Bowhead Whales Can Cool Themselves Down Using an Erectile Organ on the Roof of their Mouth

Bowhead whales have a large palatal retial organ (roof of the mouth). Here they have a bulbous ridge of highly vascularised tissue (called the corpus cavernosum maxillaris) that extends down the centre line and forms two large lobes on their palate. Histological examination has revealed a large numbers of blood vessels and vascular as well as extravascular spaces that make it resemble a blood‐filled, erectile sponge, similar to that of the corpus cavernosum of the mammalian reproductive organ.

It is hypothesized that this organ provides a cooling mechanism for the whale. Protected from the cold Arctic waters the bowhead whales have a blubber layer of 40 cm (16 in) or more and sometimes needs an efficient way to cool down. During physical exertion, the whale must cool itself to prevent hyperthermia and ultimately brain damage. It is believed that this organ becomes engorged with blood and that the whale can then open its mouth to allow cold seawater to flow over the organ and thus cool the blood.

You can find the full article describing this unique cooling mechanism here.

Lifespan

The bowhead whale is the longest-lived mammal on earth. It can reach an impressive age of more than 200 years. The oldest estimated individual was 211 years old and was from Alaska (Vasquez et al., 2022). It was estimated using aspartic acid racemisation rates in the eye lens nucleus. Recoveries of traditional whale-hunting tools from some hunted whales also indicate lifespans in excess of 100 years of age (George et al. 1999).

Reproduction

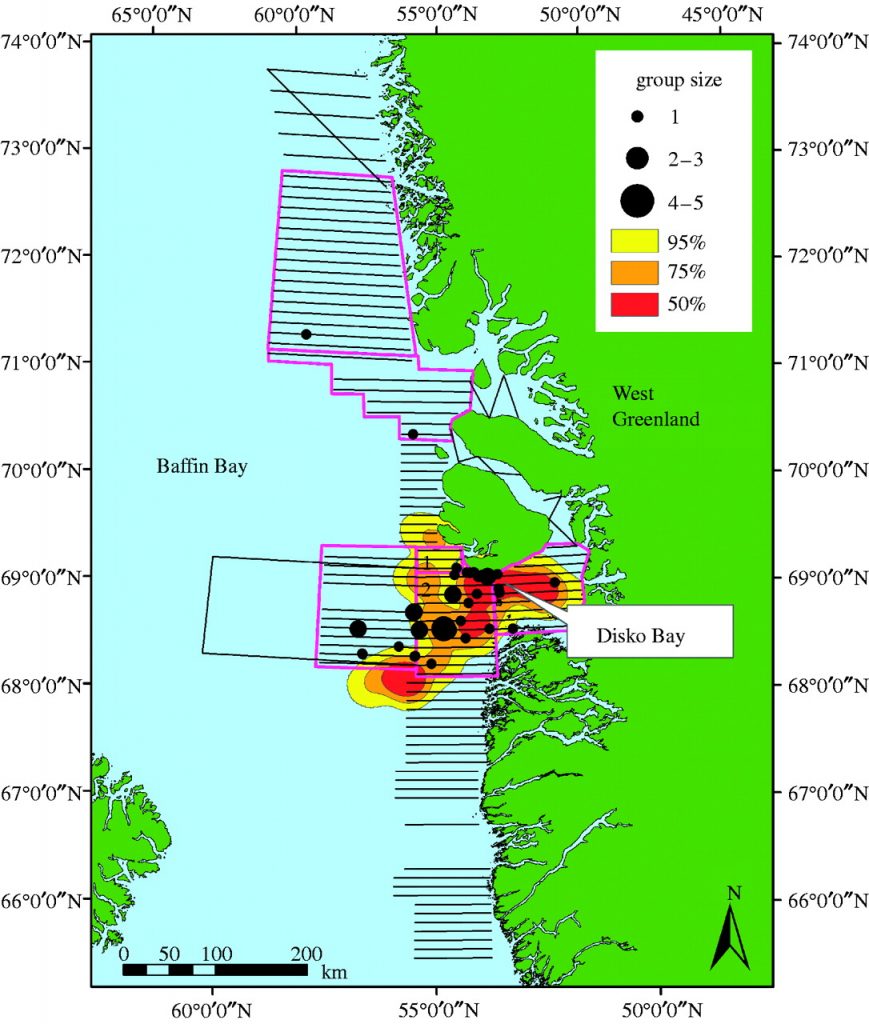

Conception in bowhead whales is believed to occur in late March (Reese et al. 2001, Heide-Jørgensen et al. 2007). Mean length of gestation was estimated to be around 14 months (Reese et al., 2001), but some recent studies suggest that female bowhead whales might be pregnant for up to 2 years (Lysiak et al., 2023), with parturition then likely occurring in May–June. Disko Bay in West Greenland is used as a spring feeding ground and probably also a mating ground for bowhead whales from the ECWG stock Near-term pregnant females have been observed in this area, however females are rarely accompanied by calves. Parturition in this stock thus likely occurs after the whales have visited Disko Bay in April–May, probably around the same time as the Bering-Chukchi-Beaufort Sea stock (Heide-Jørgensen et al. 2012a).

Female and male bowhead whales reach sexual maturity at around 25 years of age (Rosa et al. 2013) and at around 13 m in length (George et al. 2004, Heide-Jørgensen et al. 2012a, O’Hara et al. 2002).

Near-term foetuses have been measured to be 3.9–4.3 m long and lengths of small calves 3.6–4.3 m have been observed in May (see Koski et al. 1993). Lactation probably lasts a year (George et al. 1999). Average calving rate is assumed to be 3–4 years and is unlikely to be less than 3 years (Koski et al. 1993).

Predators

The only known natural predator of the bowhead whale is the killer whale (Orcinus orca).

Distribution and Habitat

Bowhead whales are endemic to Arctic and subarctic waters. The bowhead whale is the only baleen whale found year-round in the Arctic. The overall distribution of bowhead whales spans approximately latitudes 54–75°N in the North Pacific basin and 60–86°N in the North Atlantic basin (Moore & Reeves, 1993). Four management stocks of bowhead whales occupy the Northern Pacific Ocean, the Northwest Atlantic Ocean, and the Northeast Atlantic Ocean.

Distribution in the North Atlantic

Bowhead whale distribution in the Northwest Atlantic includes the western Arctic Canada from the Canadian high Arctic Archipelago to Hudson Bay in the South, Baffin Bay, Davis Strait, the West coast of Greenland (with a southernmost limit at approximately 66°N (Moore & Reeves, 1993) and northern Greenland.

The stock in the Northeast Atlantic is distributed from the Greenland Sea between East Greenland to the Barents and Kara Seas.

Migration

Bowhead whales live in close association with sea ice. They are migratory of nature, generally migrating to the high Arctic in summer and moving southward in winter with the advancing ice edge. More on migration is found in the section North Atlantic stocks: Bowhead whale migration in the North Atlantic.

Management stocks

For management, at least four geographic stocks of bowhead whales are recognised. The stocks are geographically separated by landmasses or extensive sea ice. The stocks are:

- The Eastern Canada-West Greenland (ECWG) stock (Frasier et al. 2015)

- The East Greenland-Svalbard-Barents Sea stock (EGSB, earlier referred to as the Spitsbergen stock)

- The Bering-Chukchi-Beaufort Sea stock (BCB)

- The Okhotsk Sea stock (OKH)

IWC operates with the ECWG population as being two distinct stocks: the Hudson Bay-Foxe Basin stock and the Baffin Bay-Davis Strait stock. The reason behind the stock delineation was the separation of bowhead whale summering areas in Baffin Bay and Foxe Basin, and the assumption that baleen whales make seasonal north-south movements rather than east-west movements. Exchange between the bowhead whale summering populations was therefore considered unlikely.

However, neither historic nor scientific evidence has been presented confirming the separation of these two stocks. On the contrary, scientific studies based on photographic evidence and satellite tracking have linked bowhead whales between West Greenland and the Hudson Strait (Heide-Jørgensen et al. 2006). Furthermore, genetic studies support a one-stock hypothesis for the ECWG bowhead whale population. It has also been found that whales from the ECWG population are genetically distinct from the more westerly Bering-Chukchi-Beaufort population (DFO 2015).

For management purposes, particularly regarding establishing quotas for subsistence hunting, it is essential to know the stock structure of populations. The recognition of one stock of bowhead whales in Foxe Basin-Hudson Bay/Baffin Bay-Davis Strait has led to a shared quota for the stock instead of different quotas for each of the two areas (DFO 2009, 2015).

For the EGSB stock, research shows that despite the small population size, the stock has a high genomic diversity (Bachmann et al., 2021; Cerca et al., 2022).

Bowhead whale migration in the North Atlantic

Migratory patterns of bowhead whales have been documented from aerial surveys, shore- and ship-based observations, telemetry studies, and from subsistence whaling activities. Bowhead whales from the ECWG stock spend the winter in Hudson Strait, northern Hudson Bay, or along the pack-ice edge extending to coastal West Greenland. Bowhead whales may also be found in winter in the North Water Polynya, and in polynyas along the east coast of Baffin Island. In spring, the whales are found along the West Greenland coast (primarily Disko Bay), in Hudson Strait, Cumberland Sound, and the entrance to Lancaster Sound. In spring, the whales cross Baffin Bay from Disko Bay to Lancaster Sound. The whales stay within the high Canadian Arctic or along the east coast of Baffin Island in summer and early autumn and winter in Hudson Strait or at the West Greenland coast (Heide-Jørgensen et al. 2006).

- Tagging of a bowhead whale in Disko Bay with a satellite transmitter. © Mads Peter Heide-Jørgensen.

- Satellite transmitter deployed a bowhead whale in Disko Bay, Greenland. © Mads Peter Heide-Jørgensen.

Recently a study showed overlap of the ECWG stock and the Bering-Chukchi-Beaufort stock when two whales spent time in the same area in the Northwest Passage in the high Canadian Arctic (Heide-Jørgensen et al. 2012b). Sea ice in the Northwest Passage is thus perhaps not a physical barrier separating bowhead whales from the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans as previously assumed.

East Greenland-Svalbard-Barents Sea stock

The Spitsbergen stock is confined to the Northeast Atlantic from the Greenland Sea between East Greenland to the Barents and Kara Seas and into the Russian Arctic (Norwegian Polar Institute 2016). Little is known about the migratory behaviour of this small stock. A survey conducted in April 2006 found whales in Fram Strait between East Greenland and Svalbard, which is a wintering site for this population (Wiig et al. 2007). There have also been bowhead sightings from Spitsbergen fjords during summer. Historical records from whaling operations show that whales stay north and northwest of Spitsbergen in spring, and around Jan Mayen in the same seasons. Whales were also found in the Greenland Sea in May–June. The seasonal pattern for this population is “up-side down” compared to other populations that travel north in summer and south in winter (Moore & Reeves 1993).

Satellite tagging

Recent satellite tracking studies have shown that the EGSB stock occupies much of their historical range, stretching across the northern Barents Region from East Greenland eastward north of Svalbard and into Franz Josef Land and the Kara Seas in the Russian Arctic (Kovacs et al., 2020; Lydersen et al. 2012). Around the Svalbard archipelago they remain rare which was core habitat in the past (Kovacs et al., 2020; Laidre et al., 2015). Acoustic studies show that bowhead whales are found consistently in the Fram Strait, which is a wintering area and thus a mating area for this population (Ahonen et al., 2017; Stafford et al., 2012; Wiig et al. 2007). Tagged whales from Fram Strait did not migrate in a traditional way but rather dispersed during spring from their wintering grounds which are in the northernmost parts of their range, returning northward again in autumn (Kovacs et al., 2020). The Northeast Water Polynya (NEW) in the Greenland Sea is likely to be one of the most important summering grounds for this stock (Boertmann et al. 2015). During winter individuals move north and remain up to hundreds of kilometres inside the ice edge, in areas classified as having 90–100% ice concentrations (Kovacs et al., 2020). This seasonal pattern is “reversed” compared to other populations that travel north in summer and south in winter (Moore & Reeves 1993). It is speculated that the history of human exploitation of this population might be partially responsible for the habitat preference of the EGSB stock today. Bowhead whales which occupied coastal waters in the Spitsbergen population were likely eradicated, leaving only individuals that tended to inhabit areas deep into the ice protected refugia (Boertmann et al. 2015; Kovacs et al. 2020).

Current Abundance and Trends

Abundance estimates of the North Atlantic bowhead whales have been generated from aerial surveys using line transects, surveys from vessels, and from mark-recapture studies. Surveys conducted in Canada and Greenland have estimated the abundance of the ECWG stock, while those carried out by Greenland and Norway have been used for the EGSB stock.

ECWG stock

In 1981, aerial surveys of the winter range of the ECWG stock provided an estimate of a total population abundance of 1,349 (95% CI: 402–4,529) (Koski et al. 2006). Surveys carried out in Eastern Canadian and West Greenland waters after that time suggested that there were hundreds of bowhead whales present, although the range of coverage was limited, and important seasonal aggregations had often been missed (see references in Frasier et al. 2015).

In the early 2000s (2002-2004), aerial surveys of the ECWG population in Canadian waters were conducted by the Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO). Several statistical analyses suggested abundance estimates in the range from 6,344 (95% CI: 3,119–12,906) to 14,400 (95%CI: 4,811–43,105) individuals (see references in Frasier et al. 2015). In August 2013, DFO conducted the High Arctic Cetacean Survey (HACS) to update previous abundance estimates for the ECWG bowhead whale population. The survey achieved almost complete coverage of important summer aggregation areas. The fully corrected abundance estimate was 6,446 (CV 26%) (Doniol-Valcroze 2015). The estimates indicate that the ECWG population has increased significantly since bowhead whales were first protected from commercial whaling in the 1930s.

EGSB stock

Until recently, the protected EGSB stock was believed to number in the tens of animals (Lydersen et al. 2012). However, an aerial survey of bowhead whales found north of Svalbard estimated that about 300 individuals were present in this area during summer (Vacquié-Garcia et al. 2017). In summer 2009, an aerial survey estimated 102 (95 % CI: 32-329) bowhead whales in the Northeast Water Polynya (NEW) (Boertmann et al., 2015). This result showed the largest abundance of bowhead whales reported from the Greenland Sea since the whaling period and the authors concluded that the NEW could be one of the most important summering grounds for the EGSB bowhead stock and that this stock could be recovering (Boertmann et al. 2015). In 2022, two calves were observed in Scoresby Sound polynya in East Greenland, which was the first published observation of this kind in this area since the early 1900s (Tervo et al., 2023).

Total abundance in the Northern Atlantic in 2016: ~8000 bowheads

In 2016, total abundance of the North Atlantic bowhead whale stocks (the ECWG stock and the EGSB stock) was estimated as being nearly 8,000 animals.

Based on Bayesian analyses of genetic mark-recapture data, Frasier et al. (2015) estimated a total abundance estimate of 7,660 (95% CI: 4,500–11,100) for the ECWG bowhead whale population. The results are consistent with a population increase throughout the 19-year study period.

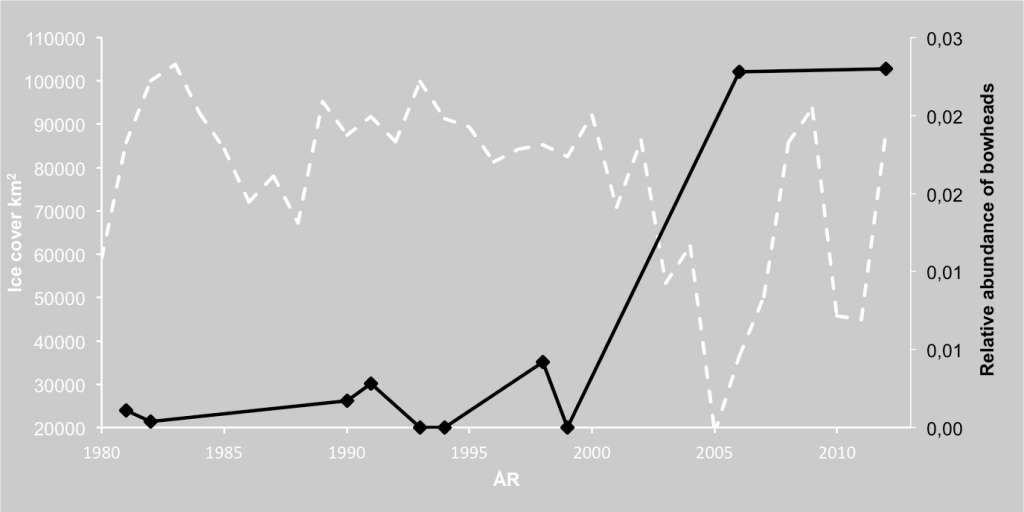

A case study: Increasing abundance of bowhead whales in West Greenland

A study by Heide-Jørgensen et al. 2007, showed a significant increase in the winter population abundance of bowhead whales on the former whaling grounds in West Greenland. The result was surprising, as the change in abundance couldn’t be explained by recent or rapid growth in population size. One hypothesis was that the population, which showed a higher abundance of mature females, had recently attained a certain threshold size elsewhere. Heide-Jørgensen et al. also noted that a severe reduction in sea ice facilitated access to coastal areas and that these two factors in combination could explain the increase in the occurrence of whales in the area.

Consequently, a survey in west Greenland documented the largest number of bowhead whales recorded in the area for the past 100 years. This was a first clear indication that the population was increasing (Heide-Jørgensen et al. 2007). A recent study from 2015, however, indicates that the observed increase in abundance (between 1998 and 2006) has levelled off (Rekdal et al. 2015).

Regional status

Bowhead whales have been protected since 1931, apart from limited and low levels of subsistence whaling. Only the ECWG stocks and the Bering–Chukchi–Beaufort stock are subject to subsistence whaling, while the two other recognised management stocks are fully protected.

Three out of the four bowhead whale stocks seem to be increasing in abundance (see Table below). For the Okhotsk Sea, data is insufficient for estimating abundance but according to IWC, the population appears small and is subject to both anthropogenic and natural pressures (IWC 2016a). IWC recommends that an abundance estimate be obtained for this population.

Abundance estimates, trends, and current status from the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species (IUCN 2016) for the four bowhead whale stocks are also summarised in the table below. The IUCN operates with a separate status for each of the four management stocks.

Conservation status according to other international organisations

The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) lists the bowhead whale as one mega-population, grouping the four recognised stocks in Appendix I – ‘threatened with extinction’. CITES does not distinguish between the status of the different stocks. As is the case for the fin whale (see also fin whale–Stock status), pooling of different populations together under a single listing can be misleading as the stocks are by definition reproductively isolated and may have very different conservation histories. This is particularly misleading when the populations pooled together are very different in size, as is the case for the ECWG and Bering-Chukchi-Beaufort stocks, which are much larger than the EGSB and Okhotsk Sea stocks (NAMMCO ).

Abundance estimates, trends in abundance and stock status of bowhead whale stocks worldwide.

| Bowhead Whale Stock | Abundance estimate | 95% Confidence Intervals | Trend | IUCN* Status | Method | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eastern Canada – West Greenland | 7,660 | 4,500 – 11,100** | Increasing | Least concern | Genetic capture-mark-recapture (2008-12) | Frasier et al., 2015 |

| East Greenland – Svalbard – Barents Sea | 343 | 136 – 862 | Increasing | Vulnerable | Helicopter- and ship-based surveys (2015) | Vacquié-Garcia et al., 2017 |

| Bering – Chukchi – Beaufort Seas | 12,361 | 7,900 – 19,700 | Increasing | Least concern | Photo-identification | Koski et al., 2010 |

| Okhotsk Sea | No available estimate, but presumably small (a few hundred) | N/A | Unknown | Endangered | None | IWC, 2016 |

*From IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature), the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

**A fully corrected line transect estimate for 2013 for all the major summering areas of the bowhead population in East Canada, excluding Foxe Basin, Repulse Bay and Lancaster Sound gave an abundance estimate of 6,446 (CV: 26%) (Doniol-Valcroze et al. 2015). Number of whales visiting West Greenland was estimated to 1,274 (CV=0.12) for 2012 via mark-recapture (IWC 2015).

Management

In the North Atlantic, the bowhead whale is managed by two international management organisations: the North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO) and the IWC, for those countries that are members. Canadian takes are managed domestically.

Commercial bowhead whaling was banned in 1931. Canada and Greenland resumed hunting bowhead whales from the ECWG stock in 1996 and 2008 in the form of subsistence whaling.

Management measures in NAMMCO member countries

The last updated list of laws and regulations in NAMMCO countries regarding the hunting of marine mammals (including protection and hunting methods) can be found here.

Greenland

The Ministry of Fisheries and Hunting regulates and administers hunting in Greenland (Government of Greenland 2016). Some of the regulations apply to hunting in general (Home Rule Act no. 12, 29-10-1999, and later amendments in 2001, 2003 and 2008), animal welfare (Home Rule Act no. 25, 18-12-2003), nature protection (Home Rule Act no. 29, 18-12-2003), and hunting permits (Executive order nr. 20, 27-12-2003), while others specifically address the hunting of large whales. In addition to the rules of the Government of Greenland, there may also be additional rules set by the municipalities.

There is no private ownership of land, sea or living resources in Greenland. Hunting grounds and game animals are open to hunt and use by Greenlandic citizens, subject to hunting licenses. However, only persons with a full-time occupational hunting license are allowed to hunt large whales and there are several important conditions and limitations, including those related to catch limits, methods of hunting, training and reporting.

Locally, a team of wildlife officers/wardens control hunting and fishing activities, making sure that conservation measures of protected areas and species are respected and are passing information on to the local community. The wildlife officers work in close cooperation with the municipalities, the police, and the Government of Greenland.

The IWC determines the catch quotas for bowhead whales taken in Greenland. The “quota year” for bowhead whales is from April 1st to December 31st.

Norway

Bowhead whales are fully protected in Norway. Whaling is under the authority of the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Fisheries (Government of Norway 2016). Currently, the common minke whale is the only whale species that can be legally hunted in Norway.

Hunting and utilisation

Subsistence hunting for bowhead whales by Inuit in Canada, Greenland and Alaska is important providing traditional food and livelihoods, and for sustaining cultural traditions and values. Although the bowhead whale populations have been protected from commercial hunts since 1931, the Inuit in Canada, Greenland and Alaska can catch a limited number of whales under management regimes for subsistence whaling. The small number of whales hunted by indigenous people in Canada is managed domestically. Quotas for catches in Greenland and Alaska are set by the IWC (IWC 2016b). Inuit in Canada resumed bowhead whale hunting in 1996, and 24 bowhead whales were taken in the period 1996-2014 (DFO 2015). Inuit in Greenland resumed bowhead whale hunting in 2008, and 8 bowhead whales have been taken in the period 2008-2019.

The bowhead whale was almost hunted to extinction by European and American commercial whalers over a nearly 400-year period between the 1500s and the 1900s. All stocks of bowhead whales were exploited. Currently, of the two North Atlantic stocks, only the ECWG stock is exploited while the EGSB stock is fully protected throughout its range.

ECWG stock

Eastern Canada

In Eastern Canada, two Inuit communities—the Nunavut Settlement Area and the Nunavik Marine Region (northern Quebec)—resumed subsistence hunts for bowhead whales in 1996 and in 2008, respectively. The hunts are co-managed by the Nunavut Wildlife Management Board, the Nunavik Marine Region Wildlife Board, and Fisheries and Oceans Canada. Hunting is licensed by the DFO (DFO 2015).

It has been estimated that the ECWG bowhead whale population can support a total human-induced mortality of 52 whales annually, resulting from all sources of anthropogenic mortality including hunt, struck and loss, net entanglements, and ship collisions (Doniol-Valcroze 2015). The current annual level of total allowable hunt is five bowhead whales in Nunavut and two in Nunavik. It is prohibited to catch calves less than 7.6 m in length and females accompanied by calves (DFO 2015). The table to the right lists the bowhead catches in Eastern Canada from 1996 to 2014, a total of 24 catches.

West Greenland

The West Greenland hunt for bowhead whales from the ECWG stock resumed in 2008 under conditions established by the IWC (DFO 2015). In 2014, the IWC re-approved two strikes per year for West Greenland with the requirement for an annual review by the IWC Scientific Committee. The catch history of bowhead whales in West Greenland since 2008 is listed in the table below. The Government of Greenland allows unused catches to be transferred to the following year.

Subsistence hunts of ECWG bowhead whales in Nunavut (NU) and Nunavik (QC) since 1996

| Year | Community | Sex | Length (m) |

| 1996 | Repulse Bay, NWT1 | M | 14.91 |

| 1998 | Pangnirtung, NWT1 | M | 12.75 |

| 2000 | Coral Harbour, NU | M | 11.65 |

| 2002 | Igloolik, NU | F | 14.19 |

| 2005 | Naujaat, NU | F | 16.40 |

| 2008 | Sanirajak, NU | M | 13.43 |

| Kulgaaruk, NU | M | 10.51 | |

| Kangiqsujuaq, QC | M | 14.88 | |

| 2009 | Rankin Inlet, NU | F | 16.15 |

| Kinngait, NU | M | 15.77 | |

| Kangiqsujuaw, QC | F | 17.29 | |

| 2010 | Mittimatalik, NU | M | 12.80 |

| Naujaat, NU | F | 14.32 | |

| 2011 | Coral Harbour, NU | F | 16.38 |

| Iqaluit, NU | M | 14.33 | |

| Kugaaruk, NU | F | 9.04 | |

| 2012 | Arctic Bay, NU | M | 8.99 |

| Naujaat, NU | M | 8.10 | |

| Taloyoak, NU | F | 9.60 | |

| 2013 | Pangnirtung, NU | M | 12.80 |

| Naujaat, NU | F | 15.72 | |

| Gjoa Haven, NU | M | 9.75 | |

| 2014 | Clyde River, NU | F | 16.00 |

| Kugaaruk, NU | M | 13.10 | |

| 2015 | Naujaat, NU | F | 14.00 |

| 2016 | Igloolik, NU | F | 8.23 |

| Pangnirtung, NU | F | 11.74 | |

| 2017 | Kangiqsujuaq, QC | F | 14.00 |

| 2018 | Naujaat, NU | F | 15.93 |

| Iqaluit, NU | F | 10.97 | |

| Coral harbor, NU | M | 8.23 | |

| 2019 | Coral harbor, NU | F | 8.00 |

| Naujaat, NU | F | 14.27 | |

| Mittimatalik, NU | F | 9.14 | |

| Igloolik, NU | F | 9.19 | |

| 2020 | Sanirajak, NU | M | 12.65 |

| 2021 | Coral Harbour, NU | F | 10.00 |

| Baker Lake, NU | M | 14.00 |

1Prior to 1999 when Nunavut separated from the Northwest Territories.

Catches in NAMMCO member countries since 1992

| Country | Species (common name) | Species (scientific name) | Year or Season | Area or Stock | Catch Total | Quota (if applicable) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greenland | Bowhead whale | Balaena mysticetus | 2023 | Baffin Bay-Davis Strait | 0 | 2 |

| Greenland | Bowhead whale | Balaena mysticetus | 2022 | Baffin Bay-Davis Strait | 1 | 2 |

| Greenland | Bowhead whale | Balaena mysticetus | 2021 | Baffin Bay-Davis Strait | 0 | 2 |

| Greenland | Bowhead whale | Balaena mysticetus | 2020 | Baffin Bay-Davis Strait | 0 | 2 |

| Greenland | Bowhead whale | Balaena mysticetus | 2019 | West | 0 | 0 |

| Greenland | Bowhead whale | Balaena mysticetus | 2018 | West | 0 | 4 |

| Greenland | Bowhead whale | Balaena mysticetus | 2017 | West | 0 | 4 |

| Greenland | Bowhead whale | Balaena mysticetus | 2016 | West | 0 | 4 |

| Greenland | Bowhead whale | Balaena mysticetus | 2015 | West | 1 | 4 |

| Greenland | Bowhead whale | Balaena mysticetus | 2014 | West | 0 | 4 |

| Greenland | Bowhead whale | Balaena mysticetus | 2013 | West | 0 | 2 |

| Greenland | Bowhead whale | Balaena mysticetus | 2012 | West | 0 | 3 |

| Greenland | Bowhead whale | Balaena mysticetus | 2011 | West | 1 | 2 |

| Greenland | Bowhead whale | Balaena mysticetus | 2010 | West | 3 | 3 |

| Greenland | Bowhead whale | Balaena mysticetus | 2009 | West | 3 | 4 |

| Greenland | Bowhead whale | Balaena mysticetus | 2008 | West | 0 | 2 |

| Greenland | Bowhead whale | Balaena mysticetus | 2007 | West | 0 | 2? |

| Greenland | Bowhead whale | Balaena mysticetus | 1992-2006 | West | *No reported catches | |

This database of reported catches is searchable, meaning you can filter the information, e.g. by country, species or area. It is also possible to sort it by the different columns, in ascending or descending order, by clicking the column you want to sort by and the associated arrows for the order. By default, 30 entries are shown, but this can be changed in the drop-down menu, where you can decide to show up to 100 entries per page.

Carry-over from previous years are included in the quota numbers, where applicable.

You can find the full catch database with all species here.

For any questions regarding the catch database, please contact the Secretariat at nammco-sec@nammco.no.

Hunting methods in NAMMCO countries

People’s right to hunt and utilise marine mammals is a firmly established principle in NAMMCO, and hunting conditions and techniques have always been priority issues. Embedded in this right is also an obligation to conduct the hunt in a sustainable way and in such a way that it minimises animal suffering (NAMMCO 2010a).

Greenland

Besides annual hunting quotas, a number of regulations have to be met for bowhead whale hunting to be legal in West Greenland. Hunters are required to hold a valid full-time occupational hunting license, a species-specific license, an approved harpoon gun, and mandatory fishing gear to be allowed to take part in the bowhead whale hunt. Furthermore, hunters must attend a course in the use of ‘whale-grenades’ to be allowed to buy and handle those grenades. The hunter that holds the bowhead-license also must report his plans for the hunt of the bowhead whale to the authorities.

The bowhead whale can only be hunted between April 1st and December 31st. Only adult whales can be taken and calves as well as females with calves are fully protected. The actual bowhead whale hunt requires three whale hunting boats of at least 11 m. Mandatory hunting gear on the boats includes a harpoon gun (calibre of at least 50 mm with approved whale grenades for large whales) and a line or trawl winch with a tractive force of at least five tonnes. Furthermore, the boats must be equipped with buoys that prevent the whale from sinking. A wounded bowhead whale has to be put down using a ‘whale-grenade’ shot to the breast-region.

Once killed, the whales have to be flensed at a location approved by the authorities. All parts of the whale must be used. If there’s too much meat for the hunters themselves to use or sell, the remaining meat must be given to the local community.

Furthermore, the catch has to be reported to the authorities before it can be sold, and a tissue sample delivered to the local authority. There can also be regulations regarding where it is allowed to hunt whales and where only whale-safaris can take place (Government of Greenland 2016).

Bowhead whale caught in Disko Bay, West Greenland, in 2009. © Greenland Institute of Natural Resources.

Past and current hunt

A tragic whaling history

The need for blubber, meat, oil, bones, and baleen started the European hunt for whales in the Arctic region. The bowhead whale, a fat, slow swimmer that floats after death, was an ideal target for the European, and later American, whaling ships to exploit. The original or ‘traditional’ form of commercial whaling was distinct from ‘modern’ commercial whaling, which was characterised by fast, motorised vessels with harpoon guns. The exploitation of the bowhead whale precedes the era of modern commercial hunting and ended in the early 1900s (Ross 1993).

© Wikimedia

The start and subsequent expansion

Whaling for bowhead whales, also called the Greenland whale, polar whale or simply whale at the time, began off the southern coast of Labrador around 1540. As the whaling for bowhead whales in this area levelled off towards termination in the early 1600s, bowhead whaling started near Spitsbergen. The whaling activities continued and by the year 1700, had expanded into the Davis Strait region and into Hudson Bay in 1860. By the late 19th century, when whaling was in its last phase, whalers were hunting bowhead whales throughout the North Atlantic sector. In the 19th century, American whalers went for the bowhead whales in the Sea of Okhotsk and the Bering, Chukchi, and Beaufort seas (Ross 1993). The hunt for bowhead whales thus continued over almost four centuries at levels driving the bowhead stocks close to extinction.

Estimating the total catch

It has been estimated that since 1530, 70,000 bowhead whales were landed in Eastern Canada and West Greenland – a figure that combines commercial and Inuit hunts using data from revised previous catch series (Higdon 2010). This estimate is without struck-and-lost animals. To maintain the overall killed whales, struck-and-lost animals ought to be added (struck-and-lost rates of 15–20% have previously been used by Mitchell (1977)).

Protection

In 1931, the League of Nations Convention protected the bowhead whale from commercial whaling. Some limited subsistence whaling was still carried out by Inuit in Alaska though. In 1946, IWC was established by the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling. The IWC continued the prohibition on commercial whaling starting in 1931 and began to regulate commercial whaling among signatory nations in 1964. In 1977, the IWC called for a ban on the increasing subsistence bowhead whaling in Alaska due to concerns about the status of the whale populations. A full ban was not implemented, instead, the IWC granted a limited quota (Reeves & Leatherwood 1985).

Stock sizes prior to commercial whaling

Several attempts at estimating pre-exploitation stock sizes of bowhead whales have been performed. Historical records and population models (often in combination) have been used for these attempts. However, such estimation is a difficult exercise due to a lack of both a complete catch record and basic information on biological parameters.

Woodby and Botkin (1993) have estimated the pre-exploitation stock size for the Spitzbergen stock to be 25,000, Davis Strait 11,000, Hudson Bay 575, Bering Sea 18,000 and the Okhotsk Sea 6,500. In 2006, Allen and Keay reconstructed the Greenland-Spitzbergen bowhead population throughout the period of commercial exploitation by European whaling vessels (1611–1911). The estimate of approximately 52,500 adult bowhead whales resident in the waters between the east coast of Greenland and Spitsbergen in 1611 was calculated using species-specific biological parameters, a delayed-difference recruitment model, and historical whaling records. The estimate of Allen and Keay (2006) was more than double of the previous estimate from Woodby and Botkin (1993). Also, Higdon (2010) suggests that using his revised catch series would improve estimates of pre-exploitation population size over previous attempts.

These few examples give an indication of the complexity of estimating pre-exploitation stock sizes of commercially hunted whales. Regardless of the exact size of the pre-exploitation population, there is no doubt that there were numerous bowhead whales in the Arctic and sub-Arctic waters prior to the start of the whaling era. The removal of that many large marine mammals in a fairly short period of time can be assumed to have had an enormous impact on the Arctic ecosystems (Allen & Keay 2006).

© Fernando Ugarte

ACOUSTIC POLLUTION

Acoustic pollution is one of the new ‘threats’ facing bowhead whales. Anthropogenic noise in Arctic waters is increasing as human activity increases as a consequence of climate change. Lesser sea ice and an extended open-water season expand the possibilities for exploration and exploitation for oil and gas in the Arctic region. An increase in shipping and shipping routes in otherwise previously impassable regions is also expected (Reeves et al.2014). In addition, noise from military activity (e.g. sonar), helicopters and airplanes, and marine constructions add to the overall acoustic load now present in Arctic waters, which were previously largely devoid of anthropogenic noise.

As marine mammals rely heavily on both hearing and producing sounds for a number of vital behaviours like communication and navigation, prey detection, predator avoidance, and mate selection, any increase in underwater sound levels can affect these important functions (Blackwell et al. 2015).

Bowhead whales have been seen to decrease their calling rates during autumn migration in the Alaskan Beaufort Sea when they were in proximity to seismic operations. When sound levels were above a certain threshold, the whales were virtually silent. The effects on the animals from such a change in behaviour are unknown (Blackwell et al. 2015).

CLIMATE CHANGE AND ANTHROPOGENIC IMPACTS

Reductions in sea ice as a consequence of climate change will likely have negative effects on some marine mammals, for example, seals that give birth to pups on ice. However, the reliance of the ice-associated whales on sea ice-mediated ecosystems is more unclear (Laidre et al. 2008, Moore and Huntington 2008). Reductions in sea ice may actually enhance feeding opportunities for bowhead whales on prey both produced in and/or advected to their summer and autumn habitats (Moore & Laidre 2006). Despite roughly two decades of sea ice loss in the Alaskan Beaufort Sea, the Bering-Chukchi-Beaufort population has increased steadily at a growth rate of 3.4%, suggesting that sea ice reduction is not hindering recruitment to this population as it rebounds from overhunting during commercial whaling (George et al. 2004). Potential consequence of ice loss is increase in predation from killer whales (Willoughby et al., 2020). Anticipated changes for the bowhead whale populations could, however, include migration alteration and occupation of new feeding areas (Moore & Huntington 2008). Overall, their capacity to adapt to new or different food resources will play a key role in their success in a changing environment (Kovacs et al., 2011).

Future seasonal changes in habitat for bowhead whales during predicted ocean warming East and West of Greenland between 2020 and 2100 were modelled by Chambault et al. (2022). They used two climate scenarios, business as usual and a second one which assumes a warming below 2°C. The models predicted a north-westward expansion of bowhead whales’ habitat in West Greenland into the Canadian Arctic Archipelago in winter. In East Greenland, the animals will lose most of their current habitat under the business as usual, but under the second scenario, some new habitat might become available further north. In summer, the models projected a northerly shift of key habitats, with a significant habitat loss for both sides, with the most loss suggested under the first scenario. Predicted habitats are expected to decrease in summer for both scenarios −68% (±15.3) and −28% (±53.7) respectively. In summer, bowhead whales of West Greenland are predicted to shift northward 475 km (± 261 km) under the second scenario.

Around Svalbard, observations of bowhead whales have increased north of the archipelago and decreased in coastal areas and fjords of the archipelago. This is coupled with a retreating sea-ice edge, which they are associated with (Bengtsson et al., 2022).

Although bowhead whales may benefit from lesser sea ice through increased access to prey, the bowhead whales face a growing number of anthropogenic threats as the Arctic becomes more accessible for humans. The impact on bowhead whale populations of potential risks like oil spills, collisions with ships, increased ocean pollution, emissions from mining activities etc. remain, for now, uncertain.

Research in NAMMCO member countries

Bowhead whales are the subject of extended research activities in both Greenland and Norway. This includes photo identification work (Heide-Jørgensen & Finley, 1991), satellite telemetry studies (Heide-Jørgensen et al. 2003, 2006, 2012a, Lydersen et al. 2012, Kovacs et al. 2020), acoustic analyses (Stafford et al. 2012, 2018, Tervo 2009, 2011, 2012a,b, Ahonen et al. 2017), genetic research (Borge et al. 2007, Rekdal et al. 2015, Keane et al. 2015) and studies on age and reproduction (Heide-Jørgensen et al. 2012a). This work has expanded our knowledge of bowhead whale migration patterns, stock structure, behaviour, and life-history. Surveys (Boertmann et al. 2015, Heide-Jørgensen et al. 2007, Vacquié-Garcia et al. 2017) have also added to our knowledge through creating estimates of abundance.

RECENT AND ONGOING STUDIES

Greenland

Rekdal et al. (2015) used two different methods for estimating abundance and trends of bowhead whales in Disko Bay, West Greenland: aerial survey and genetic mark-recapture approach. They found that the two abundance estimates were complementary. The aerial survey provided a snapshot that is useful for examining the local trend without dependence between years. The genetic mark-recapture approach estimates the size of the actual source population, but this approach is considered less suited for time series estimates as it would require samples over many years. The authors concluded that although the two approaches do not necessarily lead to identical estimates, in combination, they give valuable insight into trends affecting abundance and the fraction of the population that is present within the surveyed area (Rekdal et al. 2015).

Long-term studies of bowhead whales in Disko Bay are ongoing. In 2018 and 2019, these studies focused on testing technology for combining satellite telemetry and recording sounds on the surface of whale bodies, in order to better understand the effects of noise from seismic air guns. Oceanographic tags that record temperature, salinity, depth and position are also under development (National Progress Report Greenland 2019). The focus for 2020 is on the collection of biopsy samples for mark-recapture abundance estimates (National Progress Report Greenland 2020).

In 2019, hunters from Qeqetarsuaq collected biopsies of bowhead whales during spring in Disko Bay. These will be used by the Greenland Institute of Natural Resources for mark-recapture abundance estimates (National Progress Report Greenland 2018, 2019).

Boertmann et al. (2015) took advantage of an aerial survey for walrus (Odobenus rosmarus) in part of the Northeast Water Polynya (NEW) and observed several bowhead whales, resulting in an abundance estimate of 102 (95 % CI: 32–329) individuals. The otherwise fairly inaccessible area has only recently been visited by researchers. The authors concluded that the NEW might be one of the most important summering grounds for the EGSB stock and proposed that their results provide renewed hope that this stock was recovering from depletion due to commercial whaling (Boertmann et al. 2015).

Norway

Norwegian waters have been monitored acoustically since 2008. Passive acoustic recorders were placed in Fram Strait (Stafford et al. 2012, Moore et al. 2011) and Chukchi Plateau (Moore et al. 2011) to sample this part of bowhead whale habitat. Over a six-year period, 2008–2014, an autonomous underwater acoustic recorder (AURAL) was installed in western Fram Strait to investigate the soundscape of this important breeding ground of bowhead whales (Ahonen et al. 2017). In the same area in western Fram Strait, another acoustic study was conducted where omni-directional hydrophone recorders were deployed and redeployed annually from 2010 to 2014 in September. This study documents extremely high inter- and intra-annual diversity in the mammalian song from the EGSB bowhead whale population (Stafford et al. 2018). AURALS deployed also on the eastside of Svalbard show presence of bowhead whales throughout the winter and into the summer as long as the area has ice cover (Llobet et al. 2023

During summer of 2015, a study that involved helicopter- and ship-based line transects was conducted in ice-covered areas from the Russian border in the east (35°E) to northwest of Svalbard in the west (7°E) and estimated the number of bowhead whales in this area (Vacquié-Garcia et al. 2017).

Bowhead whales are also monitored by biologging and biotelemetry. First ever satellite tagging of EGSB stock was a female bowhead whale tagged on 3 April 2010 in Fram Strait (Lydersen at al. 2012). In July 2017, 16 satellite transmitters were deployed from a helicopter to study movement and space use relative to environmental conditions within seasons (Kovacs et al. 2020). In a study by Hamilton et al. 2021, biotelemetry data from marine mammals tagged around the Svalbard Archipelago, in the northern Barents Sea, Fram Strait, and along the northeast coast of Greenland during the period 2005−2019 was collected and analysed (Hamilton et al. 2021). In period 2017–2019, 23 biologging devices were deployed in EGSB as a part of the study that had the aim to identify hotspots and areas of high species richness for Arctic marine mammals (Hamilton et al. 2022).

Ahonen, H., Stafford, K. M., de Steur, L., Lydersen, C., Wiig, Ø., & Kovacs, K. M. (2017). The underwater soundscape in western Fram Strait: Breeding ground of Spitsbergen’s endangered bowhead whales. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 123(1–2), 97–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2017.09.019

Allen, R.C. and Keay, I. (2006). Bowhead Whales in the Eastern Arctic, 1611–1911: Population Reconstruction with Historical Whaling. Environment and History, 12(1), 89–113. https://doi.org/10.3197/096734006776026791

Bengtsson, O., Lydersen, C., & Kovacs, K. M. (2022). Cetacean spatial trends from 2005 to 2019 in Svalbard, Norway. Polar Research, 41. https://doi.org/10.33265/polar.v41.7773

Blackwell, S.B., Nations, C.S., McDonald, T.L., Thode, A.M., Mathias, D., Kim, K.H., Greene, C.R. and Macrander, A.M. (2015). Effects of Airgun Sounds on Bowhead Whale Calling Rates: Evidence for Two Behavioral Thresholds. PLOS ONE, 10(6), e0125720. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0125720

Blackwell, S. B., Tervo, O. M., Lemming, N. E., Quakenbush, L. T., & Heide-Jørgensen, M. P. (2022). Drift Dives in a Bowhead Whale (Balaena mysticetus). Aquatic Mammals, 48(6), 656–660. https://doi.org/10.1578/AM.48.6.2022.656

Boertmann, D., Kyhn, L.A., Witting, L. and Heide-Jørgensen, M.P. (2015). A hidden getaway for bowhead whales in the Greenland Sea. Polar Biology, 38(8), 1315–1319. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00300-015-1695-y

Borge, T., Bachmann, l., Bjørnstad, G. and Wiig, Ø. (2007). Genetic variation in Holocene bowhead whales from Svalbard. Molecular Ecology, 16(11), 2223–2235. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03287.x

C. Shane Reese, Calvin, J.A., George, J.C. and Tarpley, R.J. (2001). Estimation of Fetal Growth and Gestation in Bowhead Whales. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 96(455), pp.915–938. https://doi.org/10.1198/016214501753208618.

Cerca, J., Westbury, M. v., Heide-Jørgensen, M. P., Kovacs, K. M., Lorenzen, E. D., Lydersen, C., Shpak, O. v., Wiig, Ø., & Bachmann, L. (2022). High genomic diversity in the endangered East Greenland Svalbard Barents Sea stock of bowhead whales (Balaena mysticetus). Scientific Reports, 12(1), 6118. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-09868-5

Chambault, P., Kovacs, K. M., Lydersen, C., Shpak, O., Teilmann, J., Albertsen, C. M., & Heide-Jørgensen, M. P. (2022). Future seasonal changes in habitat for Arctic whales during predicted ocean warming. Science Advances, 8(29). https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abn2422

Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO). (2009). Advice on selective hunting of Eastern Canadian Arctic-West Greenland bowhead whales. DFO Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat, Sci. Advis. Rep. 2008/057. Available at http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/csas-sccs/Publications/SAR-AS/2008/2008_057-eng.htm

Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO). (2015). Updated abundance estimate and harvest advice for the Eastern Canada-West Greenland bowhead whale population. DFO Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat, Sci. Advis. Rep. 2015/052. Available at http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/csas-sccs/Publications/SAR-AS/2015/2015_052-eng.html

Doniol-Valcroze, T., Gosselin, J.-F., Pike, D., Lawson, J., Asselin, N., Hedges, K. and Ferguson, S. (2015). Abundance estimate of the Eastern Canada – West Greenland bowhead whale population based on the 2013 High Arctic Cetacean Survey. DFO Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat, Res. Doc. 2015/058. v + 27 p. Available at http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/csas-sccs/Publications/ResDocs-DocRech/2015/2015_058-eng.html

Finley, K.J. (2001). Natural history and conservation of the Greenland whale, or bowhead, in the Northwest Atlantic. Arctic, 54(1), 55-76. https://doi.org/10.14430/arctic764

Frasier, T.R., Petersen, S.D., Postma, L., Johnson, L., Heide-Jørgensen, M.P. and Ferguson, S.H. (2015). Abundance estimates of the Eastern Canada-West Greenland bowhead whale (Balaena mysticetus) population based on genetic capture-mark-recapture analyses. DFO Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat, Res. Doc. 2015/008. iv + 21 p. Available at http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/csas-sccs/publications/resdocs-docrech/2015/2015_008-eng.html

George, J.C., Bada, J., Zeh, J., Scott, L., Brown, S.E., O’Hara, T. and Suydam, R. (1999). Age and growth estimates of bowhead whales (Balaena mysticetus) via aspartic acid racemization. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 77(4), 571–580. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjz-77-4-571

George, J. C., et al. (2021). Life History, Growth, and Form. In J. C. George & J. G. M. Thewissen (Eds.), The Bowhead Whale (Balaena mysticetus): Biology and Human Interactions (pp. 87–115). London, UK: Academic Press.

J. Craig George, Rugh, D. and Suydam, R. (2018). Bowhead Whale. Elsevier eBooks, pp.133–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-804327-1.00075-3.

George, J.C., Zeh, J., Suydam, R. and Clark, C. (2004). Abundance and population trend (1978–2001) of western Arctic bowhead whales surveyed near Barrow, Alaska. Marine Mammal Science, 20(4), 755–773. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-7692.2004.tb01191.x

Government of Greenland. (2016). Fangst og jagt.

Government of Norway. (2016). Whaling and seal hunting. Available at https://www.regjeringen.no/en/topics/food-fisheries-and-agriculture/fishing-and-aquaculture/whaling-and-seal-hunting/id2504696/

Haldiman, J.T. and Tarpley, R.J. (1993). Anatomy and physiology. In J.J. Burns, J.J. Montague, C.J. and Cowles (eds.), The Bowhead Whale. Special Publication No.2, 71-156. Society for Marine Mammalogy, Lawrence, KS. 787pp.

Hamilton, C.D., Lydersen, C., Aars, J., Acquarone, M., Atwood, T., Baylis, A., Biuw, M., Boltunov, A.N., Born, E.W., Boveng, P., Brown, T.M., Cameron, M., Citta, J., Crawford, J., Dietz, R., Elias, J., Ferguson, S.H., Fisk, A., Folkow, L.P. and Frost, K.J. (2022). Marine mammal hotspots across the circumpolar Arctic. Diversity and Distributions, 28(12), pp.2729–2753. https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.13543.

Hamilton, C., Lydersen, C., Aars, J., Biuw, M., Boltunov, A., Born, E., Dietz, R., Folkow, L., Glazov, D., Haug, T., Heide-Jørgensen, M., Kettemer, L., Laidre, K., Øien, N., Nordøy, E., Rikardsen, A., Rosing-Asvid, A., Semenova, V., Shpak, O. and Sveegaard, S. (2021). Marine mammal hotspots in the Greenland and Barents Seas. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 659, pp.3–28. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps13584.

Hansen R.G., Boye T.H., Larsen R.S., Nielsen N.H., Tervo O.M., Nielsen R.D., Rasmussen M.H., Sinding M.H.S. & Heide-Jorgensen M.P. 2017. Abundance of whales in west and east Greenland in summer 2015. NAMMCO Scientific Publications 11, doi: 10.1101/391680

Heide-Jørgensen, M.P. and Finley, K.J. (1991). Photographic reidentification of a bowhead whale in Davis Strait. Arctic, 44(3), 254–256. https://doi.org/10.14430/arctic1546

Heide-Jørgensen, M.P., Laidre, K., Wiig, Ø., Jensen, M.V., Dueck, l., Maiers, l.D., Schmidt, H.C. and Hobbs, R.C. (2003). From Greenland to Canada in ten days: Tracks of bowhead whales, Balaena mysticetus, across Baffin Bay. Arctic, 56(1), 21–30. https://doi.org/10.14430/arctic599

Heide-Jørgensen, M.P., Laidre, K.L., Jensen, M.V., Dueck, L. and Postma, L.D. (2006). Dissolving stock discreteness with satellite tracking: bowhead whales in Baffin Bay. Marine Mammal Science, 22(1), 34–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-7692.2006.00004.x

Heide-Jørgensen, M.P., Laidre, K., Borchers, D., Samarra, F. and Harry, S. (2007). Increasing abundance of bowhead whales in West Greenland. Biology Letters, 3(5), 577–580. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2007.0310

Heide-Jørgensen, M.P., Garde, E., Nielsen, N.H. and Andersen, O.N. (2012a). Biological data from the hunt of bowhead whales in West Greenland 2009 and 2010. Journal of Cetacean Research and Management, 12(3), 329–333. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2011.0731

Heide-Jørgensen, M.P., Laidre, K.L., Quakenbush, L.T. and Citta, J.J. (2012b). The Northwest Passage opens for bowhead whales. Biology Letters, 8(2), 270–273. Available at https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2011.0731

Higdon, J.W. (2010). Commercial and subsistence harvests of bowhead whales (Balaena mysticetus) in eastern Canada and West Greenland. Journal of Cetacean Research and Management, 11, 185–216. Available at https://archive.iwc.int/pages/search.php?search=%21collection15&k=

International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). (2016). the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, Okhotsk Sea Bowhead Whale. Available at http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/2469/0

The International Whaling Commission (IWC). (2015). Report of the Scientific Committee. Annex F. Report of the Sub-Committee on Bowhead, Right and Gray Whales. Journal Cetacean Research and Management, 16, 158–75. Availablae art https://archive.iwc.int/pages/search.php?search=%21collection15&k=

The International Whaling Commission (IWC). (2016a). Report of the Scientific Committee. Report of the International whaling Commission, 66, 1–136.

The International Whaling Commission (IWC). (2016b). Aboriginal Subsistence Whaling. Available at https://iwc.int/aboriginal

Johnson, D.H., Stafford, K.M., George, J. and Clark, C.W. (2014). Song sharing and diversity in the Bering-Chukchi-Beaufort population of bowhead whales (Balaena mysticetus), spring 2011. Marine Mammal Science, 31(3), 902–922. https://doi.org/10.1111/mms.12196

Koski, W. R., Davis, R. A., Miller, G. W. and Withrow, D. E. (1993). Reproduction. In J.J Burns, J.J Montague and C.J. Cowles (eds.), The Bowhead Whale. Special Publication No.2, 239-274. Society for Marine Mammalogy, Lawrence, KS. 787pp.

Koski, W.R., Heide-Jørgensen, M.P. and Laidre, K.L. (2006). Winter abundance of bowhead whales, Balaena mysticetus, in the Hudson Strait, March 1981. Journal of Cetacean Research and Management, 8(2), 139–144. Available at https://archive.iwc.int/pages/search.php?search=%21collection15&k=

Koski, W.R., Zeh, J., Mocklin, J., Davis, A.R., Rugh, D.J., George, J.C., et al. (2010). Abundance of Bering–Chukchi–Beaufort bowhead whales (Balaena mysticetus) in 2004 estimated from photoidentification data. Journal of Cetacean Research and Management, 11(3), 89–99. Available at https://archive.iwc.int/pages/search.php?search=%21collection15&k=

Kovacs, K. M., Lydersen, C., Overland, J. E., & Moore, S. E. (2011). Impacts of changing sea-ice conditions on Arctic marine mammals. Marine Biodiversity, 41(1), 181–194. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12526-010-0061-0z

Laidre, K. L., Stern, H., Kovacs, K. M., Lowry, L., Moore, S. E., Regehr, E. v., Ferguson, S. H., Wiig, Ø., Boveng, P., Angliss, R. P., Born, E. W., Litovka, D., Quakenbush, L., Lydersen, C., Vongraven, D., & Ugarte, F. (2015). Arctic marine mammal population status, sea ice habitat loss, and conservation recommendations for the 21st century. Conservation Biology, 29(3), 724–737. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12474

Laidre, K.L., Stirling, I., Lowry, L.F., Wiig, Ø., Heide-Jørgensen, M.P. and Ferguson, S.H. (2008). Quantifying the sensitivity of Arctic marine mammals to climate-induced habitat change. Ecological Applications, 18(sp2), S97–S125. https://doi.org/10.1890/06-0546.1

Lydersen, C., Freitas, C., Wiig, Ø., Bachmann, L., Heide-Jørgensen, M.P., Swift, R. and Kovacs, K.M. (2012). Lost Highway Not Forgotten: Satellite Tracking of a Bowhead Whale (Balaena mysticetus) from the Critically Endangered Spitsbergen Stock. Arctic, 65(1), 76–86. https://doi.org/10.14430/arctic4167

Lysiak, J., Ferguson, S.H., Hornby, C.A., Heide-Jørgensen, M.P. and Matthews, D. (2023). Prolonged baleen hormone cycles suggest atypical reproductive endocrinology of female bowhead whales. Royal Society Open Science, 10(7). https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.230365.

Mitchell, E.D. (1977). Initial population size of bowhead whale, Balaena mysticetus, stocks: cumulative estimates. Paper SC/29/33 presented to the IWC Scientific Committee meeting, Canberra, Australia, June 1977.

Mitchell, E.D. and Reeves, R.R. (1981). Catch history and cumulative catch estimates of initial population size of cetaceans in the eastern Canadian Arctic. Report of the International Whaling Commission, 31, 645–682.

Moore, S.E. and Reeves, R.R. (1993). Distribution and movement. In J.J Burns, J.J Montague and C.J. Cowles (eds.), The Bowhead Whale. Special Publication No.2, 313–386. Society for Marine Mammalogy, Lawrence, KS. 787pp

Moore, S.E. and Laidre, K.L. (2006). Trends in sea ice cover within habitats used by bowhead whales in the western Arctic. Ecological Applications, 16(3), 932–944. https://doi.org/10.1890/1051-0761(2006)016[0932:TISICW]2.0.CO;2

Moore, S.E. and Huntington, H.P. (2008). Arctic marine mammals and climate change: impacts and resilience. Ecological Applications, 18(sp 2), S157–S165. https://doi.org/10.1890/06-0571.1

Moore, S.E., Stafford, K.M., Melling, H., Berchok, C., Wiig, Ø., Kovacs, K.M., Lydersen, C. and Richter-Menge, J. (2011). Comparing marine mammal acoustic habitats in Atlantic and Pacific sectors of the High Arctic: year-long records from Fram Strait and the Chukchi Plateau. Polar Biology, 35(3), pp.475–480. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00300-011-1086-y.

North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO). (2010a). Report of the NAMMCO Expert Group Meeting on Assessment of Whale Killing Data. 30pp. Available at https://nammco.no/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/nammco-report-expert-group-on-assessing-whale-killing-data-28-may-2010.pdf

North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO). (20010b). Report of the Committee on Hunting Methods. Appendix 1: List of Laws and Regulations in NAMMCO Member Countries. In NAMMCO Annual Report 2009, 44–45. NAMMCO, Tromsø, Norway. Available at https://nammco.no/topics/annual-reports/

Norwegian Polar Institute. 2016. Available at http://www.npolar.no/en/species/bowhead-whale.html

O’Hara, T.M., George, J.C., Tarpley, R.J., Burek, K. and Suydam, R.S. (2002). Sexual maturation in male bowhead whales (Balaena mysticetus). Journal of Cetacean Research and Management, 4(2), 143–148. Available at https://archive.iwc.int/pages/search.php?search=!collection15&bc_from=themes

Reeves, R.R., Ewins, P.J., Agbayani, S., Heide-Jørgensen, M.P., Kovacs, K.M., Lydersen, C., Suydam, R., Elliott, W., Polet, G., van Dijk, Y. and Blijleven, R. (2014). Distribution of endemic cetaceans in relation to hydrocarbon development and commercial shipping in a warming Arctic. Marine Policy, 44, pp.375–389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2013.10.005.

Reeves, R.R. and Leatherwood, S. (1985). Bowhead whale Balaena mysticetus Linnaeus, 1758. In Ridgway, S.H. and Harrison, R. (eds.), Handbook of marine mammals. Vol. 3. The sirenians and Baleen Whales, 305–344. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. 362 pp.

Rekdal, S.L., Hansen, R.G., Borchers, D., Bachmann, L., Laidre, K.L., Wiig, Ø., Nielsen, N.H., Fossette, S., Tervo, O. and Heide-Jørgensen, M.P. (2015). Trends in bowhead whales in West Greenland: Aerial surveys vs. genetic capture-recapture analyses. Marine Mammal Science, 31(1), 133–154. https://doi.org/10.1111/mms.12150

Rosa, C., Zeh, J., Craig George, J., Botta, O., Zauscher, M., Bada, J. and O’Hara, T.M. (2013). Age estimates based on aspartic acid racemization for bowhead whales (Balaena mysticetus) harvested in 1998-2000 and the relationship between racemization rate and body temperature Marine Mammal Science, 29(3), 424–445. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-7692.2012.00593.x

Ross, W.G. (1993). Commercial whaling in the North Atlantic sector. In J.J Burns, J.J Montague and C.J. Cowles (eds.), The Bowhead Whale. Special Publication No.2, 511–561. Society for Marine Mammalogy, Lawrence, KS. 787pp.

Simon, M., Johnson, M.,Tyack, P., Madsen, P.T. (2009). Behaviour and Kinematics of Continuous Ram Filtration in Bowhead Whales (Balaena mysticetus). Biolofical Science, 276(1674), 3819–3828. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2009.1135

Stafford, K.M., Lydersen, C., Wiig, Ø., Kovacs, K.M. (2018). Extreme diversity in the songs of Spitsbergen’s bowhead whales. Biol. Lett., 14, 20180056. http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2018.0056

Stafford, K.M., Moore, S.E., Berchok, C.L., Wiig, Ø., Lydersen, C., Hansen, E., Kalmbach, D., Kovacs, K.M. (2012). Spitsbergen’s endangered bowhead whales sing through the polar night. Endang Species Res., 18, 95-103. https://doi.org/10.3354/esr00444

Tervo, O.M., Parks, S.E. and Miller, L.A. (2009). Seasonal changes in the vocal behavior of bowhead whales (Balaena mysticetus) in Disko Bay, Western-Greenland. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 126(3), 1570. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.3158941

Tervo, O.M., Parks, S.E., Christoffersen, M.F., Miller, L.A. and Kristensen, R.M. (2011). Annual changes in the winter song of bowhead whales (Balaena mysticetus) in Disko Bay, Western Greenland. Marine Mammal Science, 27(3), E241–E252. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-7692.2010.00451.x

Tervo, O.M., Christoffersen, M.F., Simon, M., Miller, L.A., Jensen, F.H., Parks, S.E. and Madsen, P.T. (2012a). High Source Levels and Small Active Space of High-Pitched Song in Bowhead Whales (Balaena mysticetus). PLoS ONE, 7(12). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0052072

Tervo, O.M., Miller, L.A. and Christoffersen, M.F. (2012b). Simultaneous sound production in the bowhead whale Balaena mysticetus—Sexual selection and song complexity. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 132(3), 1949. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.4755171

Tervo O. M., Louis M., Sinding M.-H. S., Heide-Jørgensen M. P., & G. Hansen R. (2023). Possible signs of recovery of the nearly extirpated Spitsbergen bowhead whales: calves observed in east Greenland. Polar Research, 42. https://doi.org/10.33265/polar.v42.8809

Vacquié-Garcia J., Lydersen C., Marques T.A., Aars J., Ahonen H., Skern-Mauritzen M., Øien N. & Kovacs K.M. 2017. Late summer distribution and abundance of ice- associated whales in the Norwegian High Arctic. Endangered Species Research 32, 59–70, doi: 10.3354/esr00791.

Vazquez, J.M., Kraft, M. and Lynch, V.J. (2022). A CDKN2C retroduplication in Bowhead whales is associated with the evolution of extremely long lifespans and alerted cell cycle dynamics. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.09.07.506958.

Weir, C.R. 2023. Balaena mysticetus (Europe assessment). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2023: e.T2467A221069826. Accessed on 19 December 2023.

Wiig, Ø., Bachmann, L., Janik, V.M., Kovacs, K.M. and Lydersen, C. (2007). Spitsbergen bowhead whales revisited. Marine Mammal Science, 23(3), 688–693. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-7692.2007.02373.x

Willoughby, A.L., Ferguson, M.C., Stimmelmayr, R. et al. Bowhead whale (Balaena mysticetus) and killer whale (Orcinus orca) co-occurrence in the U.S. Pacific Arctic, 2009–2018: evidence from bowhead whale carcasses. Polar Biol 43, 1669–1679 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00300-020-02734-y

Woodby, D.A. and Botkin, D.B. (1993). Stock sizes prior to commercial whaling. In Burns, J.J Burns, J.J Montague and C.J. Cowles (eds.), The Bowhead Whale. Special Publication No.2, 387–407. Society for Marine Mammalogy, Lawrence, KS. 787pp.

Würsig, B. and Clark, C. (1993). Behaviour. In J.J Burns, J.J Montague and C.J. Cowles (eds.), The Bowhead Whale. Special Publication No.2, 157–199. Society for Marine Mammalogy, Lawrence, KS. 787pp.