Fin Whale

Latest update: February 2022, reviewed by NAMMCO’s Scientific Committee

The fin whale is the second-largest living animal, second in size only to the blue whale. Fin whales are the most streamlined in appearance of all the rorquals and have been nicknamed “razorback”. They are dark grey to brownish-black in colour along the top of the body, with an asymmetrically pigmented head. Females are slightly longer than males. Adult males average 19 m and adult females 20.5 m in the Northern Hemisphere. They weigh between 45 and 75 tonnes. Fin whale blows are tall and impressive and can often be seen at a great distance. Fin whales are sleek, fast swimmers.

ABUNDANCE

It has been estimated that there are around 80,000 fin whales in the North Atlantic (NAMMCO 2011ac; Cooke 2018).

DISTRIBUTION

Fin whales are found over the entire NAMMCO area, ranging from polar to tropical waters. They are rarely, however, found close to ice.

They are most common in the East Greenland – Iceland – Jan Mayen area (Central North Atlantic) and west of the Iberian Peninsula during summer.

RELATION TO HUMANS

Fin whales are hunted in Greenland and Iceland. The annual catches since 2000 have been:

– Greenland: between 5 and 13 whales

– Iceland: from 0 to 155 whales since 2006, when fin whaling resumed

CONSERVATION AND MANAGEMENT

Fin whales are subject to an international management regime from both NAMMCO and the International Whaling Commission.

There is clear evidence of their recovery in the North Atlantic. The population is now likely close to or larger than before the onset of modern whaling in the 1880s.

The populations of the Central stock (EG+WI+[EI+F]) and the West Greenland area (WG), the two areas from which catches are taken, are considered in a healthy state and able to sustain a managed harvest (see assessments: IWC 2016, NAMMCO 2017).

In the most recent assessment (2023), the species is listed as ‘Least Concern’ on the regional European IUCN Red List. The species is ‘Least Concern’ in Norwegian and Icelandic national red lists.

Fin whale in Greenland © Fernando Ugarte

Scientific name: Balaenoptera physalus (Linnaeus 1758)

Faroese: Nebbafiskur

Greenlandic: Tikaagulliusaq

Icelandic: Langreyður

Norwegian: Finnhval

Danish: Finhval

English: Common rorqual, finback, fin-backed whale, finner, herring whale, razorback

Average Size

19-21 m long, 45-75 tonnes in the Northern Hemisphere. Females are larger than males.

Lifespan

Up to 85-90 years.

Productivity

One calf every 2-3 years from 7-12 years of age.

Feeding

‘Lunge-feeding’ on euphausids, and small pelagic fish. The extendable ventral grooves enable fin whales to engulf up to 80 tons of prey and seawater before squeezing out the latter through the rows of baleen plates (Shadwick et al. 2019).

Migration

Between high-latitude feeding grounds in summer and lower-latitude breeding grounds in winter (most populations).

General Characteristics

The fin whale is the second largest living animal, second in size only to the blue whale. This large baleen whale belongs to the Balaenopteridae family, also called rorquals.

AT SEA

Fin whales are the most streamlined in appearance of all the rorquals. The distinct ridge along their back behind the dorsal fin gives them the nickname “razorback” (Leatherwood and Reeves 1983).

Fin whales are sleek, fast swimmers. Their exceptionally large size, streamlined appearance and the small falcate dorsal fin appearing just after the blow are probably their best identifying feature. Another key identifying feature is their asymmetrical head coloration. This is particularly useful for distinguishing a fin from a sei whale.

Fin whale blows are tall and impressive and can often be seen at a great distance. They can reach as much as six metres in height and are shaped like a slim inverse cone.

CHARACTERISTICS

Fin whale off Norway during a sightings survey in 2014. © K.A. Fagerheim, Institute of Marine Research, Norway

Fin whales have a falcate dorsal fin, which is about 60 cm high and set about two-thirds back along the body. Their jaw is large and when the mouth is closed, the lower jaw protrudes slightly beyond the tip of the snout. Their flukes show slightly concave trailing edges, but are rarely raised out of the water.

Fin whales are dark grey to brownish black in colour along the top of the body, while the throat, belly and undersides of the flippers and tail flukes are white. Some fin whales have a pale grey chevron on each side behind the head. They may have a dark stripe running up and back from the eye, as well as a light stripe arching down to where the flipper joins the body.

As other rorquals, the fin whale has grooves along the ventral side of the body. In this species, there are 55 to 100 such grooves running from the underside of the lower jaw to beyond the navel.

Asymmetry

The head of a fin whale has a single medial ridge and asymmetric pigmentation, with the ventral white colouration extending up over the right lower lip and inside the mouth cavity and the baleen plate. In contrast, the left side of the jaw is quite dark. The asymmetrical coloration pattern on the head is reversed on the tongue. Why fin whales have this asymmetrical pigmentation, which is rare among mammals, is not known, although it has been speculated that it may have something to do with their feeding strategy.

A series of 260-475 baleen plates hang on either side of the upper jaw. They measure up to 90 cm in length and 30 cm in width at the base. The baleen plates on the left side of the mouth have alternating bands of creamy-yellow and blue-grey colour. On the right side, the forward 1/3 of the plates are all creamy-yellow.

SIZE

Males and females are very similar in their general appearance, but females are slightly longer than males. Adult males average 19 m while adult females in the Northern Hemisphere average 20.5 m, and are slightly longer in the south, averaging a little over 22 m. Adult fin whales weigh between 45 and 75 tonnes, depending on the time of year and their individual body condition.

Lifespan

The age of fin whales, as other rorquals (balaenopteridae), can be estimated by counting the growth layers present in waxy ear plugs formed in the auditory canal (Lockyer 1984, Hohn 2002). Fin whales can live at least 80-90 years. The oldest specimen captured off Iceland was 94 years old (Konráðsson & Gunnlaugsson 1990) and off Antarctica 111 years old.

Ear plug from a 57-year old Icelandic fin whale. © C. Lockyer

Reproduction

The biology of fin whales sampled from the Icelandic catch was studied between 1977 and 1989 (Lockyer and Sigurjónsson 1992). In this area, a female fin whale first gave birth between 7-12 years old and a male reached sexual maturity between 6-10 years old. The age of sexual maturity for both sexes has, however, varied significantly over time, possibly in response to food availability and/or hunting pressure (e.g. Williams et al. 2013). Physical maturity is attained at approximately 25 years of age for both sexes.

Fin whales generally have a two-year reproductive cycle, with gestation taking about 11 months and resulting in a single calf born in mid-winter. Newborn calves are approximately 6 m long and weigh 2 tonnes. Calves nurse for 6–8 months and are weaned when they are 10 to 12 m in length, when they travel with their mother to the feeding grounds. Mating and calving are thought to occur during the winter months, but no specific mating or calving grounds have been reported for fin whales.

Several hybrids of fin and blue whales, some pregnant, have been documented and 6 have been genetically confirmed (Árnason et al. 1991, Spilleart et al. 1991, Bérubé and Aguilar 1998, Cipriano and Palumbi 1999, MFRI 2018). The last hybrid was caught off Iceland in 2018 and DNA testing confirmed that the animal had a fin whale father and a blue whale mother like 5 out of 6 other known hybrids (Pampoulie et al. 2021). This particular hybrid was the first documented 2nd generation hybrid, an offspring of a female blue/fin hybrid and a male fin whale.

FEEDING

Fin whales are known to have a broad diet in the North Atlantic, including krill (euphausiids), copepods and pelagic fish such as capelin, juvenile herring and blue whiting (Sergeant 1966, Mitchell 1975, Overholtz and Nicholas 1979, Woodley and Gaskin 1996, Sigurjónsson and Víkingsson 1997, Bloch and Joensen 1985). Squid may also be eaten in some areas. In the Northeast Atlantic, however, the main prey seems to be the swarming euphausiids Meganyctiphanes norvegica.

Fin whales can consume up to 2-3 tonnes of food a day. However, feeding activity varies greatly by season due to variation in prey abundance. It is vital for fin whales to build up energy reserves in the form of stored fat and blubber during the summer, since prey are less available in the wintering areas. During winter, daily food intake may be as low as a tenth of the summer intake.

PREDATORS

Due to their large size and fast swimming ability, fin whales have very few natural predators. However, calves and even adults may occasionally be taken by killer whales.

Worldwide Distribution

The fin whale has a worldwide distribution. It occurs in the Atlantic, Pacific, Indian and Arctic Oceans. In all oceans, it ranges from tropical to polar regions, primarily in temperate to polar latitudes. It is rarely found in tropical or ice-covered polar seas.

Fin whales are largely pelagic (open-ocean dwellers), but may be seen in coastal waters in some areas, sometimes occurring in waters as shallow as 30 m.

At least 3 distinct worldwide populations are recognized – Southern Hemisphere, North Atlantic and North Pacific. These populations are further subdivided genetically (e.g. Martin 1990). The Committee on Taxonomy of the Society for Marine Mammalogy provisionally recognizes three subspecies, the northern fin whale, Balaenoptera physalus physalus; the southern fin whale, B. p. quoyi, and the pygmy fin whale, B. p. patachonica and some taxonomists classify fin whales from theNorth Pacific as a separate subspecies (Cooke 2018). Northern and Southern Hemisphere populations rarely meet or mix across the equator because the seasonal patterns are reversed in the two hemispheres, meaning that they migrate to the equator at different times of year.

In the central and western Mediterranean, there is a subpopulation, which is genetically differentiated from that of the North Atlantic (Bérubé et al. 1998).

DISTRIBUTION IN THE NORTH ATLANTIC

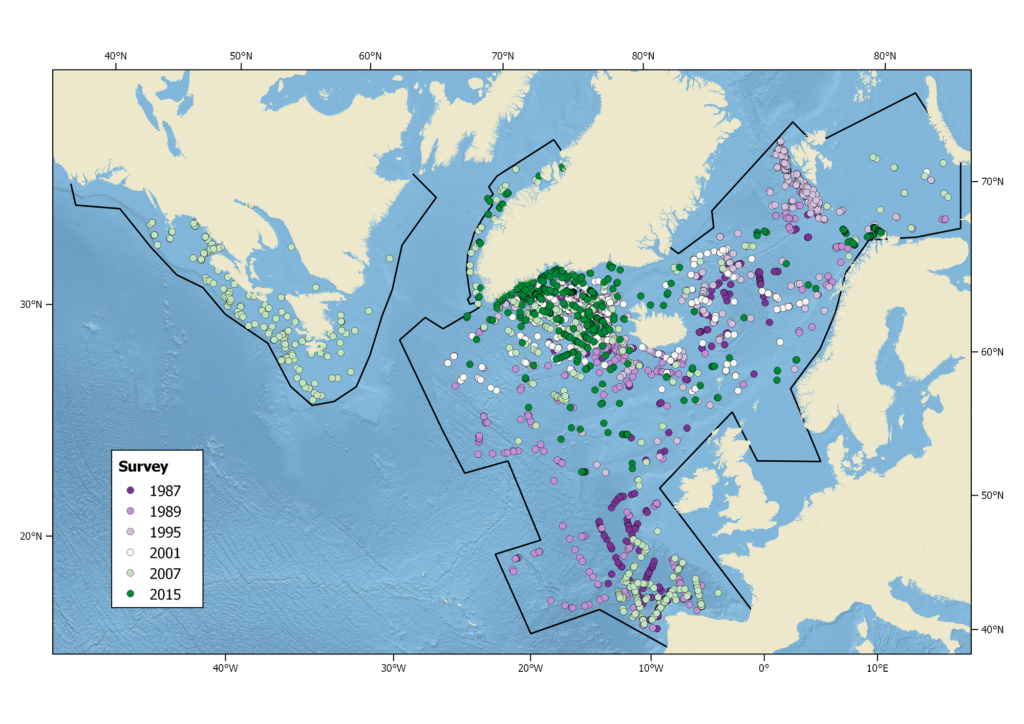

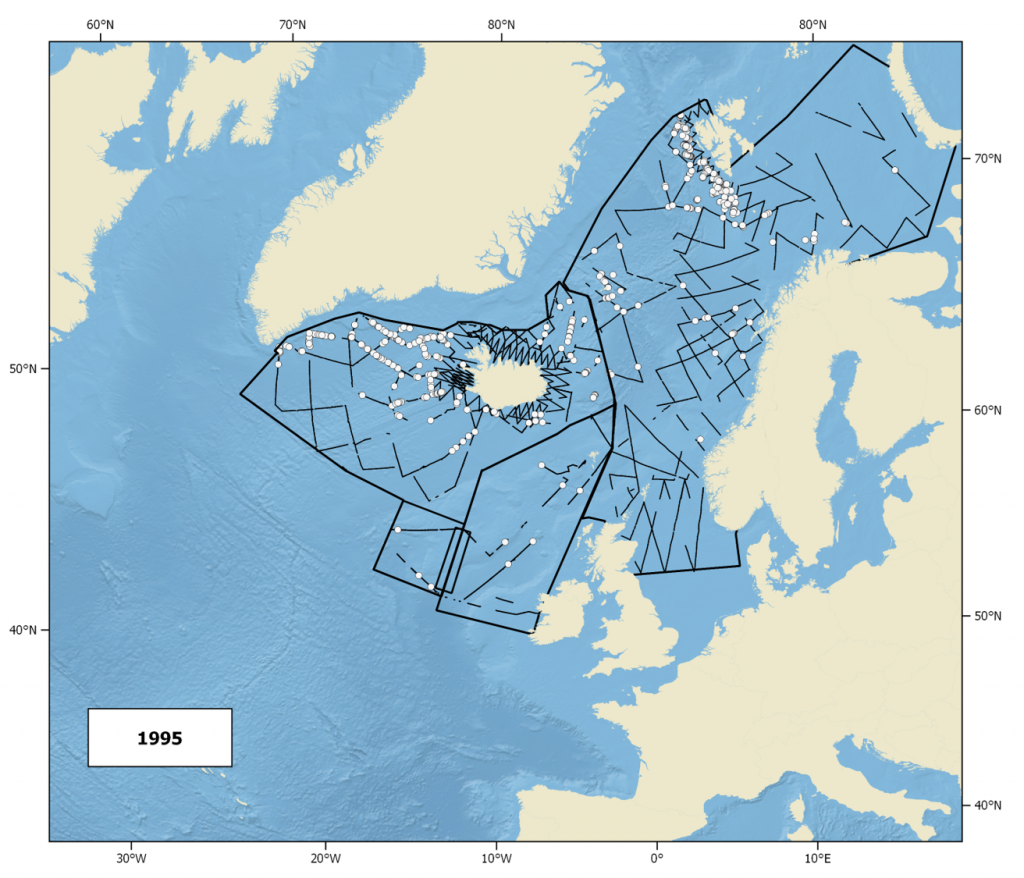

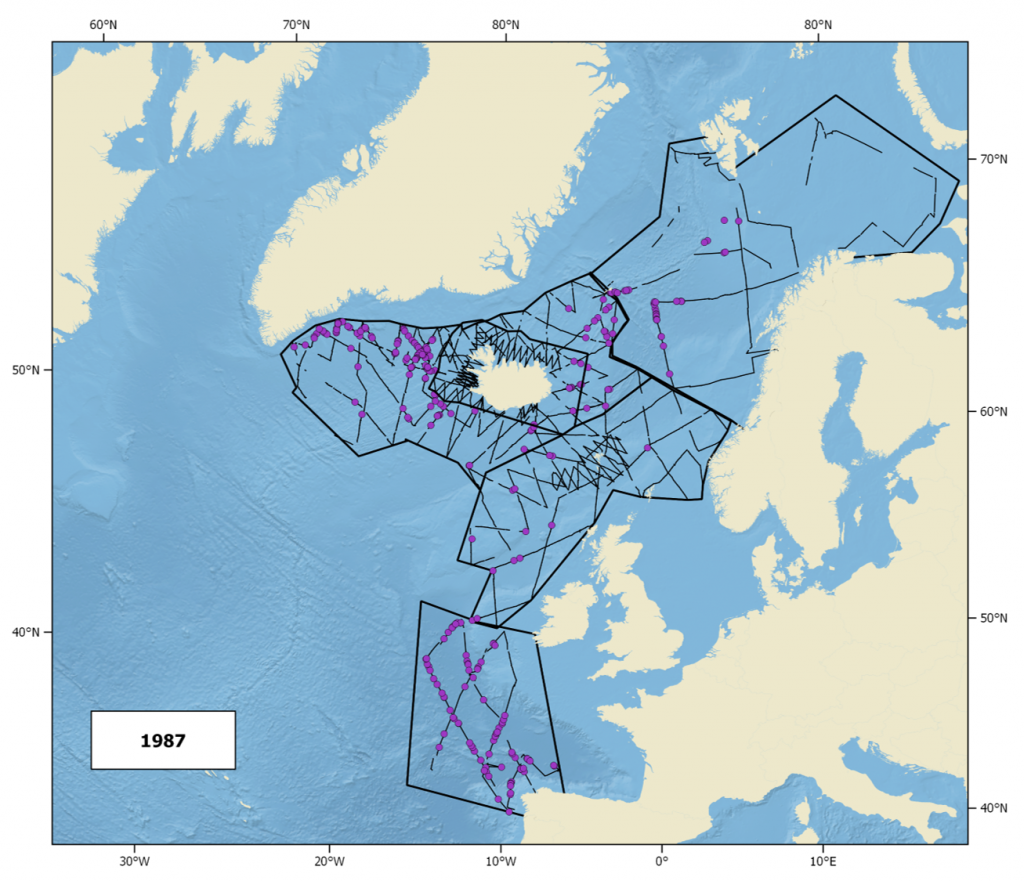

The 28-year long series of NASS and T-NASS summer sightings surveys provides a good understanding of the potential summer distribution of the species in the northern part of the North Atlantic. These surveys are conducted during 3-4 weeks in mid summer (July). .

The species is present in summer over the entire NAMMCO area, ranging from temperate to polar waters. At this time of year, it is most common off Nova Scotia and Newfoundland, in the Davis Strait off Western Greenland, in the East Greenland – Iceland – Jan Mayen area and west of the Iberian Peninsula.

MIGRATION

Fin whales are migratory. They exhibit seasonal north-south movements between lower latitudes in winter to find warm breeding grounds for mating and calving and high latitudes in summer to exploit cold feeding grounds, although they likely forage during migration as well (Kellogh 1929, Mackintosh 1965, 1966; Lydersen et al. 2020). When transiting, fin whales can sustain high swim speeds (average horizontal speed of 9.3km/h) for periods as long as a week (Lydersen et al 2020). These migrations do not, however, necessarily involve the entire population and several resident populations are known to exist, as in the Mediterranean (Lockyer 1984, Mizroch et al. 2009).

North Atlantic fin whales may occur to some extent throughout the year in all of their range (as suggested by acoustic data (Clark 1995)), although the density of individuals in any one area may change seasonally.

Fin whales are not usually seen in groups near islands or coasts and are difficult to study, for instance due to their pelagic occurrence and large spatial movements, as well as harsh conditions for data collection at high latitudes Clear migratory routes and wintering (breeding) grounds have not yet been identified. A recent tagging study in Svalbard found a portion of tagged individuals staying in the local area throughout autumn and early winter, while the rest moved in a south-westerly direction, with some travelling as far as the coast of northern Africa (Lydersen et al. 2020).

New techniques have recently permitted monitoring of the acoustic activity of cetaceans, bearing witness to their presence and activities. This is done over long-time periods and independently of weather, sea, ice and light conditions (Mellinger et al. 2007). Monitoring fin whales’ acoustic activity for 2 years in the Davis Strait between Greenland and Canada has provided new information on the migratory pattern and habitat use. Fin whales were shown to be present in the area from June to at least the end of December (Simon et al. 2010). This means that at least part of the population migrate south much later than October, as previously believed (e.g. Norris 1967, Heide-Jørgensen et al. 2008). Furthermore, not all fin whales seem to migrate south to mate, some remain at high latitudes in late autumn and early winter, presumably continuing to feed , staying as far north as 81.68°N in Svalbard (Lydersen et al. 2020).

Fin whales © T. Jacobsen, PolarImage.dk

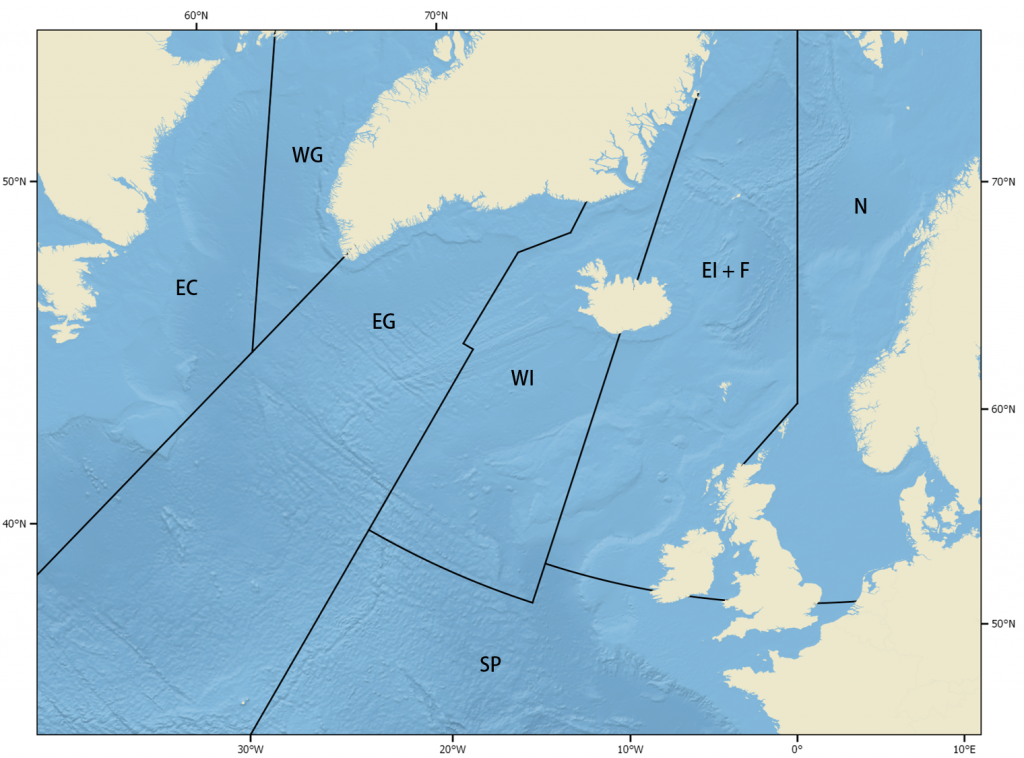

STOCK DEFINITION

Morphometrics (body size and shape) and genetic studies point to the existence of several stocks of fin whales in the North Atlantic (Daníelsdóttir et al. 1991, 1992, Jover 1991, Bérubé et al. 1998). In addition, fin whales can be differentiated into regional groups by the sounds they make (Hatch and Clark 2004). However, at present, breeding grounds have not been identified for fin whales within the North Atlantic and there is not enough information to place boundaries around fin whale stocks with certainty.

FEEDING AREAS AS MANAGEMENT UNITS

For management purposes, fin whale stocks have therefore generally been defined primarily based on the summer feeding concentrations of whales. Fin whales appear to return to the same feeding grounds year after year and tagging studies have shown little relocation of whales outside of the summering stock areas in which they were tagged (IWC 1992).

Current management is based on stock boundaries proposed by the International Whaling Commission in 1977, based on the best available evidence at that time (Donovan 1991). Since then, new evidence has not been contrary to the original stock delineation but has allowed a refinement of the stock definition (IWC 2008, NAMMCO 2008).

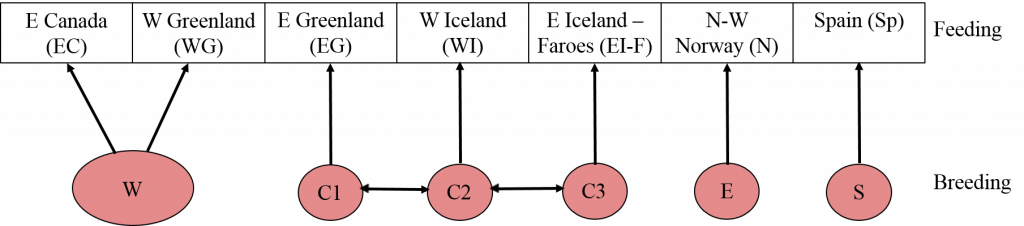

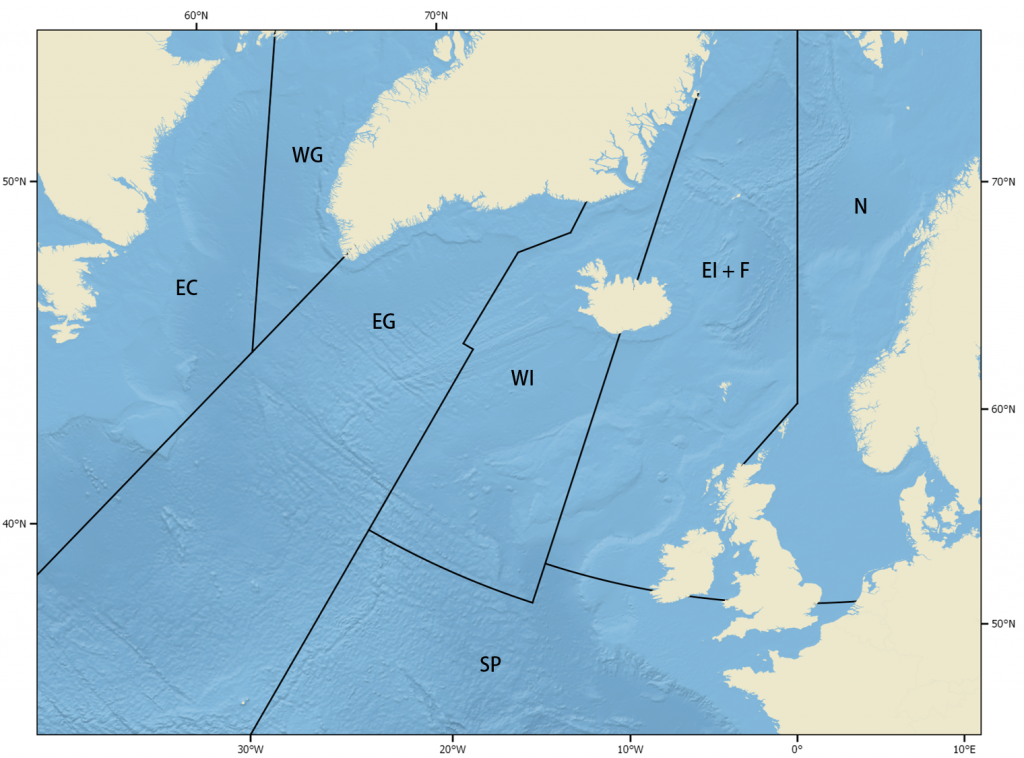

The baseline stock hypothesis distinguishes

- 7 feeding/management areas (First figure below): Canada; West Greenland; East Greenland; West Iceland; East Iceland – Faroes; North – West Norway; Spain.

- 4 breeding populations (Second figure below): West, Central, East and Spain.

- Central population split into 3 sub-populations linked by diffusive mixing (Second figure below):C1, C2 and C3.

Alternative hypotheses consider two forms of variation reagarding the baseline hypothesis:

a) different mixing of breeding stocks at the feeding grounds

b) a simplification of the baseline hypothesis by reducing the number of breeding populations from 4 to 2-3.

All of these hypotheses are used in simulation testing of various management regimes to ensure that projected levels of harvest will not be harmful to any stock.

This stock definition may not fully describe the stock structure of fin whales in the North Atlantic but it does reconcile the best the available information from genetic and non-genetic evidence and is considered safe for management purposes.

Fin whale management areas recognized by NAMMCO and the IWC.

Current Abundance and Trends

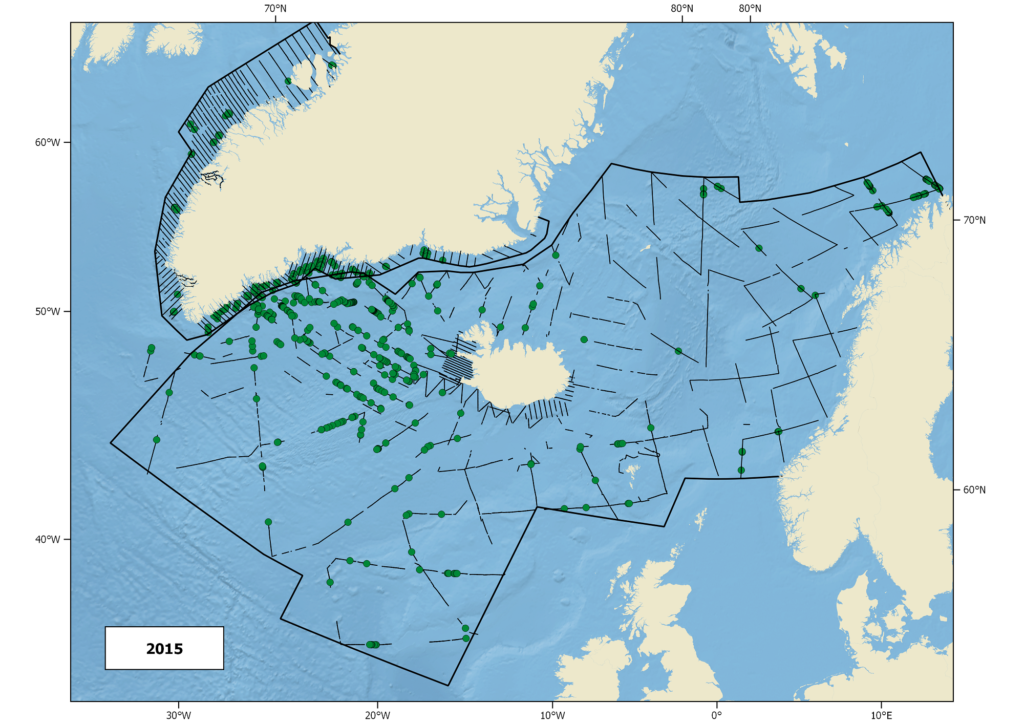

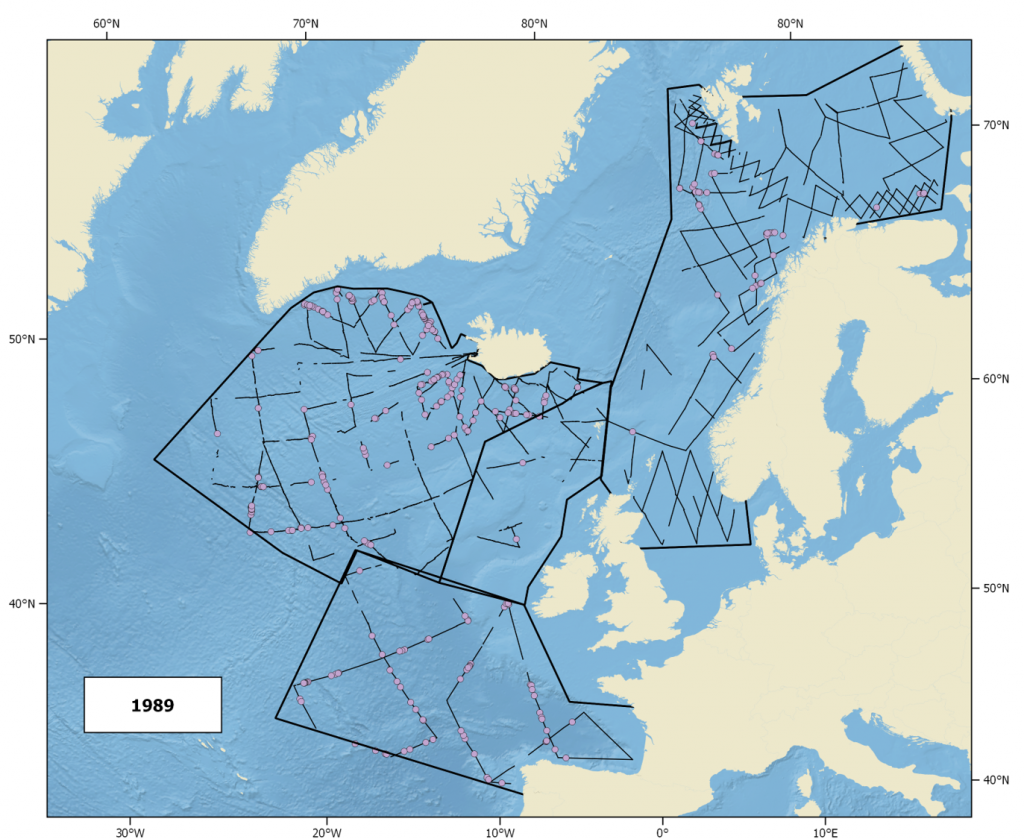

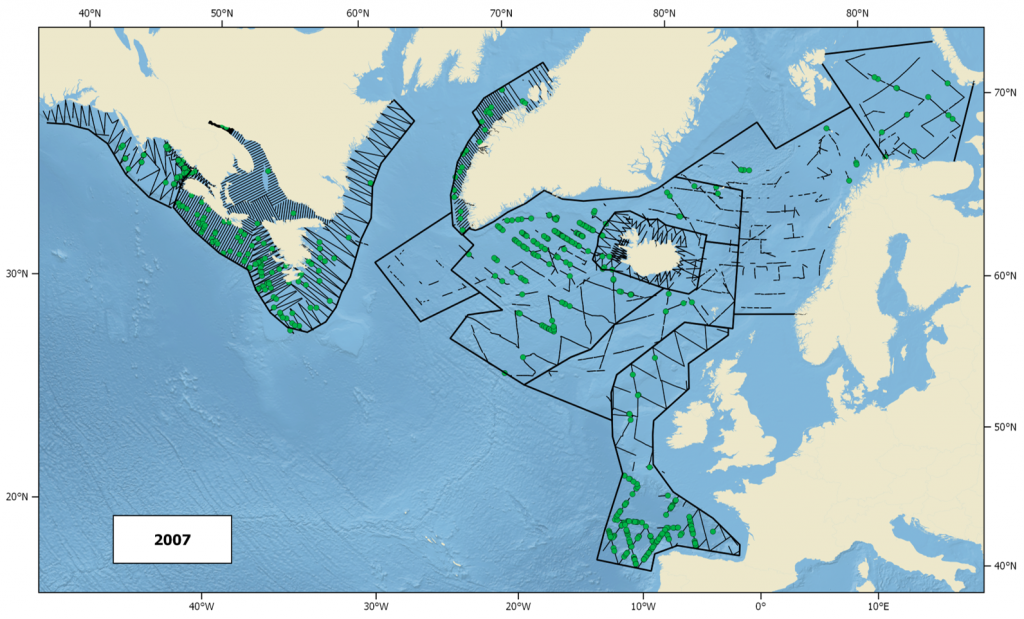

Estimates of the abundance of fin and other species of whales in the North Atlantic have been based largely on sightings surveys conducted from ships and airplanes. The North Atlantic Sightings Surveys (NASS) provide a time-series of abundance estimates from 1987 to 2015, covering a large part of the North Atlantic. Norwegian “mosaic” surveys cover most of the Northeast Atlantic, surveying a portion of the area annually on a six year rotation. Changes in distribution from year to year are incorporated into the variance of the resultant abundance estimate for minke whales (Skaug et al. 2004), but not for other species (Leonard and Øien 2020a,b). In 2007, Canada joined NASS and the first trans-Atlantic sightings survey was carried out: T-NASS. More recently, Canada carried out another large-scale survey in 2016 (Lawson and Gosselin 2018).

Other surveys that have contributed to our knowledge of fin whale abundance and distribution include the Eastern European SCANS series, in 2007 also including the survey CODA (Cetacean Offshore Distribution and Abundance), and the American SNESSA (Southern New England to Scotian Shelf Abundance).

The NASS and T-NASS surveys were conducted primarily from ships, but coastal Iceland (where few fin whales were found), West and East Greenland and Eastern Canada were surveyed by plane. See under Abundance surveys for more details on specific surveys, including timing and procedures.

FIN WHALE ABUNDANCE IN THE NORTHERN ATLANTIC IN 2007: 50,000

This number is based on the results (Figure below) of the surveys conducted in 2007 as a trans-Atlantic cooperation – SNESSA, T-NASS and CODA, as this represents the most comprehensive simultaneous survey of the North Atlantic. See under NASS/T-NASS for more information on this trans-Atlantic exercise under the NAMMCO umbrella.

The components of the overall T-NASS 2007 survey do not overlap in space, thus the surveys are additive and the estimates from each area can simply be summed. A simple sum of the estimates for CODA, Iceland-Faroes, Greenland and Canada yields a total estimate of 42,119 (CV = 0.15) (Pike et al. 2020, Heide-Jørgensen et al. 2010, Lawson and Gosselin 2011). To this may be added the estimate for the Norwegian survey area in the period 2002-2008 of 10,004 (95% CI: 6,937 – 14,426) (Leonard and Øien 2020) and recent estimates from the American eastern seaboard of about 3,000 (Palka, pers. comm.).

All of these estimates are negatively biased to a greater or lesser degree by uncorrected availability and/or other biases (see under Abundance surveys for more information on biases) and some areas of the North Atlantic that may have fin whales (e.g. Davis Strait and areas off Spain and Portugal) have not been covered by any recent surveys. Therefore, the total number of fin whales in the North Atlantic must have exceeded 50,000 in 2007 (NAMMCO 2011a,c).

FIN WHALE ABUNDANCE IN 2015/16: over 70.000

The available abundance estimates by areas are listed in the table below. All estimates are likely underestimates as the entire area of fin whale distribution was not covered in the surveys, and the Icelandic, Faroese and European ship survey estimates have not been corrected for whales that were diving when the survey ship passed (availability bias), although this bias is likely to be small. The estimates are, however, corrected for whales that were missed by the observers (perception bias).

The most recent estimates presented below are from two different years, which could potentially cause bias if fin whale distribution varies greatly between years. Nevertheless, the sum of over 70,000 fin whales from these estimates again confirms fin whales as being the most abundant large baleen whale in the North Atlantic.

| Areas 2015/16 | Estimate | 95% Confidence interval | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| West Greenland | 2,215 | 1,017 – 4,823 | Hansen et al. 2018 |

| East Greenland (coastal) | 6,440 | 3,901 – 10,632 | Hansen et al. 2018 |

| Iceland/Faroe Islands | 36,773 | 25,811 – 52,392 | Pike et al. 2019 |

| Norway (GL & NO seas) | 3,729 | 1,531 – 9,081 | Leonard and Øien 2020b |

| Canada East Coast (2016) | 4,412 | NA, CV = 0.31 | Lawson and Gosselin 2018 |

| Western Europe (2016) | 18,142 | 9,796 – 33,599 | Hammond et al. 2017 |

TRENDS IN ABUNDANCE

The NASS-TNASS series shows relatively rapid changes in the distribution and abundance of fin whales in Central North Atlantic but not in the Eastern Atlantic (Víkingsson et al. 2009, Øien 2009, Leonard and Øien 2020a,b).

Iceland

The area to the west of Iceland (WI+EG in map of fin whale management areas), between Iceland and East Greenland, in the EGI stock area, holds the most dense summer concentration of fin whales in the North Atlantic (see figure to the left).

Fin whale numbers, uncorrected for perception and availability biases, increased from 3,600 (CV=0.18) in 1987 to 14,000 (CV=0.18) in 2001, a rate of increase of 10% p.a. (95% CI: 6% – 14%) (Víkingsson et al. 2009). Abundance increased still further in 2007 and especially 2015, when it was about twice that estimated in 2001, suggesting that the fin whale stock is still growing in this area. There was no detectable trend in abundance in other areas covered by the NASS over the period 1987-2001 (Víkingsson et al. 2009).

The area west of Iceland includes the former whaling grounds and recovery from whaling certainly explains part of the increase in abundance. However, modelling of the population (IWC 2016) suggests that it should already have largely recovered from whaling. Other factors (including immigration from other areas and changes in carrying capacity) may therefore also be involved.

Increase in abundance of fin whales in the area west of Iceland

| YEAR | REGION | Abundance Estimate | 95% Confidence Interval | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1987 | WI+EG | 3,607 | 2,537 - 5,132 | Vikingsson et al. 2009 |

| 1989 | WI+EG | 6,006 | 3,468 - 10,401 | Vikingsson et al. 2009 |

| 1995 | WI+EG | 13,726 | 8,667 - 21,740 | Vikingsson et al. 2009 |

| 2001 | WI+EG | 14,021 | 9,550 - 20,586 | Vikingsson et al. 2009 |

| 2007 | WI+EG | 16,991 | 11,735 - 24,600 | Pike et al. 2020a |

| 2015 | WI+EG | 27,843 | 19,693 - 39,366 | Pike et al. 2019 |

Note that for the above table:

- The management areas – so called small areas – are not believed to be representative of stocks. They were delineated around the historical catches – for example WI and EG have a continuous distribution of fin whales and there is no evidence that there is more than one stock in this area.

- EG coastal, which has only been surveyed in 2015, has not been added to the EG 2015 abundance given in the table for sake of consistency when looking at trends. However, the coastal EG area is part of the EG management area and its abundance estimate should be added to the abundance estimate of the traditionally surveyed EG area when the purpose is to provide the best possible abundance for the EG area.

- All the values in this table are uncorrected for perception bias. Corrections are available for 2001, 2007 and 2015 but then they would not be consistent with the earlier surveys for which corrections are not available. For fin whales, the corrected values will be 10-20% higher.

Norway and Greenland

Smaller numbers of fin whales are present off Northern Norway, where there is no indication of any trend in abundance (Víkingsson et al. 2009). Estimates from Norwegian mosaic surveys have been remarkably stable since the 1996-2001 survey series, with uncorrected estimates ranging from a low of 7,094 (CV=0.15) from 2002-2007 (Leonard and Øien 2020a) to a high of 10,369 (CV=0.24) (Øien 2009), suggesting there has been little change in the area over the period.

Recent estimates of the numbers of fin whales off West Greenland have varied greatly. The most recent estimate from 2015, fully corrected for all known biases, was 2,215 (95% CI: 1,017-4,823). This is substantially lower than corrected estimates from 2005 of 9,800 (95% CI: 3,228-29,751) and from 2007 of 15,957 (95% CI: 4,531-56,202) (Hansen et al. 2018). The apparent decline cannot be explained by the catches, which are too low to have reduced numbers to this extent (less than 9 fin whales per year on average in the period 2008-2018, see Hunting and Utilisation). The reasons for the apparent decline are unclear, but likely include ongoing large scale ecosystem changes (NAMMCO 2017b, see below) and changes in fin whale distribution.

TRENDS IN ABUNDANCE IN RELATION TO CHANGE IN ENVIRONMENTAL CONDITIONS

Shifts in distribution and abundance of important prey species in the area might be a contributing factor to the observed trends, perhaps as a result of changes in sea temperature. The Figure below sets in parallel changes in sea temperature (200 m depth) between 1994 and 2003 and changes in the distribution of fin whales between 1989 and 2001. The extension of the whale distribution to the south and centre of the area seems to develop in parallel with the extension of the warmer waters (Víkingsson et al. 2015).

STOCK ASSESSMENT

NAMMCO has an ongoing programme to conduct assessments of fin whale stocks in the North Atlantic. Currently, seven stocks of fin whales are recognized by NAMMCO in the North Atlantic – Eastern Canada, West Greenland, three stocks which seem to intermix (East Greenland, West Iceland and East Iceland/Faroe Islands), Norway and Spain (NAMMCO 2007b). The Scientific Committee of NAMMCO began fin whale stock assessments in 1999 and to date has concentrated mainly on the East Greenland – Iceland – Faroes stock (usually referred to as the EGI stock) (NAMMCO 2000ab, 2001ab, 2004ab, 2006ab). An update for the northern part of the region was undertaken in 2006 in a joint workshop with the IWC (IWC 2007, NAMMCO 2007b) and continued in 2010, 2015 and 2017 when new abundance data became available (NAMMCO 2011bc, 2017a,b).

The main uncertainty concerning fin whales in the North Atlantic remains the stock structure, with a set of possible hypotheses (see North Atlantic Stocks for details) ranging from one stock covering the whole North Atlantic to five or more separate stocks – fin whales in the Mediterranean representing a separate stock (NAMMCO 2007b).

CENTRAL STOCK (EGI)

Fin whale blow off Iceland © Gísli A. Víkingsson, Marine Research Institute, Iceland

Besides recent estimates of abundance and trends in abundance estimates, the assessment of EGI fin whales is based on two sets of CPUE data (Catch Per Unit Effort), which provide information on trends in relative abundance over the 1901-1915 and 1962-1987 periods, i.e. before the series of NASS abundance surveys started.

Since 2003 (NAMMCO 2004a), the successive assessments of the EGI stock, although using different methodologies and lastly the new abundance estimate from the 2015 survey, have come to the same conclusion. The population has been increasing, although this increase has now likely ceased and is approaching or at its initial, pre-harvest abundance , with close to 30,000 whales (NAMMCO 2017, IWC 2016).

East Iceland-Faroe Islands (EI+F)

Fin whales around the Faroe Islands are now considered part of the East Iceland-Faroe Islands feeding area, however the stock relationships of these whales remains unclear (see North Atlantic Stocks). Summer abundance in the area has been around 5,000-7,000 animals, except in 2007 when it was estimated to be less than 2,000 (Pike et al. 2020a) and in 2015 when it numbered over 14,000 (Pike et al. 2019). High catches were taken in this area by commercial whalers in the 20th century. Depending on assumptions about the size of the stock area, fin whales in this area may be severely depleted (if the area is assumed to be small, for example the Faroese EEZ) or moderately depleted (if the stock area is assumed to be larger).

There are indications that fin whales around the Faroe Islands are not an isolated summer stock. A single fin whale tagged with a satellite-linked transmitter near the islands moved south to the Bay of Biscay, then returned north to an area off northwest Ireland, between August and November (NAMMCO 2003, Mikkelsen et al. 2007). There appears to be a continuous distribution of fin whales between this and adjacent areas, with no discontinuities that might indicate a stock boundary. Abundance in the area seems to vary greatly between surveys with no clear trend, again suggesting that this does not comprise a unique stock. Stock delineation remains the greatest problem for the assessment of fin whales in this area (NAMMCO 2004ab), and little progress has been made in this field.

Management Advice – EG+WI+EI/F areas

The West Iceland management area (WI), from where catches were traditionally taken, has had the highest rate of increase. This was 10% between 1987 and 2001 (Víkingsson et al. 2009, see also figures under Current Abundance and Trends) and is currently considered to be above MSY (Maximum Sustainable Yield) level (NAMMCO 2016).

In 2015, the NAMMCO Scientific Committee (SC) provided advice on sustainable catch levels in Icelandic coastal waters (the EG+WI sub-areas) suggesting that an annual catch limit of 146 fin whales in the WI sub-area was safe and precautionary (NAMMCO 2016). This was interim advice, valid for a maximum of 2 years (2016 – 2017), because of the lengthy time (8 years at that time) since the last abundance estimate for the sub-areas surrounding Iceland.

In 2017, the SC updated its advice and recommended that a catch limit of 161 fin whales in the WI area and 48 in EI/F area is safe and precautionary (based on application of the IWC’s RMP to the EG+WI+EI/F region), and that this advice should be considered valid for a maximum of 8 years, 2018 to 2025 (NAMMCO 2017).

The favourable status of North Atlantic fin whales is also reflected in a recent regional IUCN assessment for Europe where the species is not considered threatened (Temple and Terry 2007).

WEST GREENLAND STOCK

NAMMCO has not assessed the stock of fin whales off West Greenland because of the need for a newer abundance estimate and the uncertain stock affiliations of fin whales in this area. New estimates have, however, now been obtained and endorsed and an assessment could be conducted in the near future. An annual aboriginal quota of 19 whales is presently considered sustainable by the IWC (IWC 2018).

EAST OR NORTH AND WEST NORWAY STOCK

Until now, it has not yet been possible to conduct an assessment for this area. However, given the rather low abundance estimates and the high historical harvest in the area, it can be expected that the stock will be found to be depleted. With new information (for example abundance estimates, catch statistics, stock structure, etc.) now obtained for the areas, future assessment efforts can be directed towards this area.

Fin whales, North Atlantic © Guðmundur Þórðarsson, Marine and Freshwater Research Institute

OUTLOOK

Fin whales were a primary target for modern whaling. They were heavily reduced over their whole distribution range, although less so in the North Atlantic than in the North Pacific and Southern Hemisphere. The 70% overall worldwide population decline in the period 1929-2007 was mostly attributable to the major decline in the Southern Hemisphere (Reilly et al. 2008).

The recent North Atlantic surveys and trend analyses show clear evidence of recovery. The population is now likely close to or larger than before the onset of modern whaling in the 1880s, certainly numbering over 50,000 and perhaps over 70,000 fin whales (NAMMCO 2011ac, Reilly et al. 2008, see also Current Abundance and Trends for details). The favourable status of North Atlantic fin whales is also reflected in the recent regional IUCN assessment for Europe where the species is not considered threatened (Temple and Terry 2007).

For the Central North Atlantic stock (East Greenland + Iceland + Faroese areas), recent surveys and modelling suggest that the population has been increasing and that the population is approaching or at its initial, pre-harvest abundance with over 30,000 whales (NAMMCO 2004ab, 2006ab, 2007bc, 2011bc, 2016, 2017).

The West Iceland management area (WI), from where catches were traditionally taken, has had the highest rate of increase (NAMMCO 2006ac, 2007b,c, Víkingsson et al. 2009, see also Current Abundance and Trends). Although using different modelling approaches, the assessments NAMMCO has conducted since 2003 all indicate that catches of about 150 whales taken from this area would be sustainable (2004ab, 2006ab, 2007bc, 2011bc, 2016, 2017). The last assessment also indicates that catches of about 40 whales from the East Iceland/Faroese area would be sustainable.

The status of fin whales in other parts of the North Atlantic has yet not been fully assessed.

STATUS ACCORDING TO OTHER INTERNATIONAL ORGANISATIONS

International Whaling Commission (IWC)

In its “Status of Whales”, the IWC states “Assessments of the population status [of fin whales] in the central North Atlantic and off West Greenland have shown populations there to be in a healthy state”. Using a different approach to NAMMCO, the IWC Scientific Committee also concluded that catches of about 150 whales taken from the West Iceland management area would be sustainable (IWC 2010a).

International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN)

The fin whale was classified as Endangered (‘Facing a very high risk of extinction in the wild’) on the IUCN Global Red List of 2008 and 2013 (Reilly et al. 2008, 2013), but following the latest assessment in February 2018, it is now classified as Vulnerable (‘Facing a high risk of extinction in the wild’) with an increasing population trend (Cooke, 2018). However it is important to clarify that this classification refers to the global population of fin whales, rather than individual sub-specific populations, and therefore does not apply specifically to stocks in the North Atlantic (see below).

In the European Red List, it has been classified as Near Threatened (‘Close to qualifying for or is likely to qualify for a threatened category in the near future’) since 2007 (IUCN 2018).

Fin whales are classified as Least Concern in the regional Redlists of Iceland, Greenland and Norway (https://www.ni.is/midlun/utgafa/valistar/spendyr/valisti-spendyra ; https://natur.gl/raadgivning/roedliste/3-alle-arter-kilder/ ; https://www.biodiversity.no/taxon/Balaenoptera%20physalus/48147 Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES).

The fin whale is listed on CITES Appendix I: ‘Species threatened with extinction’. Iceland, Norway and Japan, which hold reservations against this listing, are not bound by it.

Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES)

The fin whale is listed on CITES Appendix I: ‘Species threatened with extinction’. Iceland, Norway and Japan, which hold reservations against this listing, are not bound by it.

COMMENTS FROM NAMMCO ON IUCN AND CITES CLASSIFICATION FOR THE FIN WHALE

Although IUCN and CITES assess many different species at the population or stock level, they do not do so for the fin whale. The fin whale is treated and listed as a single mega-population, grouping the three recognized populations of the North Atlantic, the Southern Hemisphere and the North Pacific.

NAMMCO strongly questions the scientific appropriateness of such ‘species’ listings, when the conservation status of different populations and stocks may be very different, as is the case for fin whales (latest NAMMCO 2010c). Indeed, the recent regional IUCN assessment for Europe does not consider the North Atlantic fin whales as threatened (Temple and Terry 2007, IUCN 2007).

Pooling different populations together under a single listing can be misleading as the stocks are by definition reproductively isolated and may have very different conservation histories. This is particularly dangerous when the populations pooled together are very different in size, as is the case for fin whales where the Southern Ocean population was much larger than the others.

In its ‘Status of Whales‘, the IWC express the same opinion, stating “Although often people request information on status at the species level, biologically it is more sensible to consider status at the population level (although determining stock structure, particularly for populations where the breeding grounds are unknown, is difficult). A perfect example of why this is the case is the gray whale; there is one healthy population (and thus the species is not endangered) but also one critically endangered population that therefore requires immediate conservation action”.

IUCN

In the case of the fin whale, the Southern Hemisphere population represented nearly 90% of the world fin whale population at the onset of whaling, as can be seen from the IUCN estimated population trajectory of 1920-2007 (Figure below). In its 2008 assessment, the IUCN itself stated, “Most of the global decline over the last three generations is attributable to the major decline in the Southern Hemisphere. The North Atlantic sub-population may have increased, while the trend in the North Pacific sub-population is uncertain” (Reilly et al. 2008).

Regarding the IUCN listing, NAMMCO concluded in 2009 (NAMMCO 2010c) that as long as the IUCN continues its practice of pooling all fin whale stocks into single assessments, the outcome will be completely dominated by the heavily depleted Southern Hemisphere stocks(s) and North Atlantic fin whales will be classified as endangered even if the IUCN assessment clearly shows that they would qualify for a “least concern” listing if evaluated on an individual basis.

CITES

Regarding the CITES listing, NAMMCO concluded in 2006 (NAMMCO 2007a,c) that “on the basis of biological information including population distribution, abundance and stock structure, with reference to CITES criteria A, B and C, the fin whale population in the region of the Central North Atlantic (the EGI stock) did not meet any of the biological criteria for listing under CITES Appendix I (threatened with extinction)”.

Management

Fin whale open blow holes © Kjell Arne Fagerheim, Institute of Marine Research, Norway

In the North Atlantic, fin whales fall under the management of two international management organisations, NAMMCO and the International Whaling Commission (IWC) (for those countries that are members).

Fin whaling for commercial purposes was discontinued in 1986 as a result of the temporary moratorium on commercial whaling instituted by the IWC.

In the period 1986-1989, Iceland continued taking a total of 292 fin whales for scientific research. Iceland withdrew from the IWC in 1992 and rejoined in 2002, with a reservation against the moratorium. Iceland is therefore not bound by the moratorium and resumed harvesting fin whales in 2006.

Greenland has continued to hunt fin whales under “aboriginal subsistence whaling” quotas, which do not fall under the moratorium and are issued by the IWC.

MANAGEMENT MEASURES IN NAMMCO MEMBER COUNTRIES

A list of laws and regulations in NAMMCO countries regarding hunting of marine mammals (a.o. protection and hunting methods) can be found here.

Faroe Islands – Protected

The Ministry of Fisheries is responsible for the administration of whaling regulations and for coordinating Faroese participation in the international scientific and conservation bodies that deal with the management of whale stocks (www.whaling.fo/).

Under Faroese legislation, the only cetacean species that can be harvested are pilot whales, white-beaked and white-sided dolphins, bottlenose dolphins and harbour porpoises (Executive order (Kunngerd) nr. 19, 01-03-1996). The fin whale is therefore protected and cannot be hunted in Faroese waters.

Greenland – Regulated Hunting

Hunting is regulated and administered by the Ministry of Fisheries, Hunting and Agriculture (Greenland 2012) and supervised by the Fisheries Licence Control Authority. Some of the regulations are general to hunting (Home Rule Act no. 12, 29-10-1999, and later amendments in 2001, 2003 and 2008), animal welfare (Home Rule Act no. 25, 18-12-2003), nature protection (Home Rule Act no. 29, 18-12-2003) and hunting permits (Executive order nr. 20, 27-12-2003). Others specifically address the hunting of large whales, such as executive orders no. 11 and 12 from July 16, 2010. In addition to Greenland Government rules, there may also be additional rules set by the municipality.

Hunting licences, control and quotas

There is no private ownership of land, sea or living resources in Greenland. Hunting grounds and game animals are open to harvest and use by Greenlandic citizens, subject to hunting licenses. However, only persons with a full-time occupational hunting license are allowed to hunt large whales. There are also a number of important conditions and limitations placed on this hunting, including catch limits, methods of hunting, training and reporting.

Locally, a team of wildlife officers/wardens control hunting and fishing activities. These officers make sure that the conservation measures of protected areas and species are observed and pass on information to the local community. The wildlife officers work in close cooperation with the municipalities, the police, and the Government of Greenland.

The IWC determines the (subsistence) catch quotas for all three large whale species taken in Greenland. The quota year for fin whales goes from January 1 to December 31. If the IWC fails to agree upon a subsistence quota, then Greenland sets the quota by national means following advice from the Scientific Committees of the IWC or NAMMCO. This is partly to secure the food supply and partly to avoid a situation of unregulated hunt in the absence of quota advice from the Commission.

Iceland – Regulated Hunting

Whaling is under the authority of the Icelandic Ministry of Fisheries and Agriculture. Catch limits are based on advice from the Marine and Freshwater Research Institute (MFRI), on the principle of sustainability and a precautionary approach. For further details, see here.

The advice from the MFRI is based on scientific assessments conducted within the Scientific Committees of NAMMCO and the IWC. Catch limits for whales (fin and common minke whales) used to be set annually. However, in 2009 they were set for a 5-year period, with an annual quota of 154 fin whales. In 2015, the quota was only set for two years (2016 – 2017). This was due to it being 8 years since the last abundance estimate for the sub-areas surrounding Iceland and because long-term advice was not considered feasible until the IWC RMP Implementation Review of North Atlantic fin whales had been completed (NAMMCO 2017). The annual catch limit was set to 146 fin whales in the WI sub-area. In 2017, the MFRI advised that for the period 2018-2025, the annual catch of fin whales should be no more than 161 animals from the East-Greenland/West-Iceland management area (EG/WI) and 48 fin whales from the East-Iceland/Faroe Islands management area (EI/F). More details on the advice can be found here.

Norway – Protected

Whaling is under the authority of the Norwegian Ministry of Trade, Industry and Fisheries.

Norway registered an objection to the IWC moratorium on commercial whaling and is thus not bound by it. However, Norway stopped hunting fin whales in 1971 and has not resumed hunting this species since then.

Nowadays, common minke whales are the only legally hunted whale species in Norway and fin whales are therefore protected under Norwegian law. Read more here.

Hunting and Utilisation

The fin whale has been the focus of exploitation since the advent of both vessels fast enough to catch them and harpoon guns effective in killing them. See below under Hunting methods for a description of the methods currently used in Iceland and Greenland.

The main parts of the whale anatomy targeted for utilisation have changed over time. Until the 1930s and 1940s, fin whales were mainly utilised as a resource of oil for industrial purposes. Later they became an important food resource. Bones and offal have traditionally been either discarded or processed and used as fertiliser.

In recent times, the baleen, which was originally highly prized has become redundant. The blubber, originally used for oil production, has also become of less importance. It is the red muscle – especially the back and side fillets – that are now the most desirable parts of the whales and are used as sources of meat for human consumption.

Utilisation of fin whales varies between the different NAMMCO countries.

Iceland

As in the Faroe Islands (see below), fin whales became a hunted species only in the modern whaling era. The tradition for human consumption is therefore relatively recent. Most of the fin whale meat was initially exported, but ventral groove blubber was sold locally – sour pickled whale blubber – “súr hvalrengi” – being a local delicacy.

Whale meat has always been cheap red meat for Icelanders and has been especially important in poor people’s diet. The cooking of this meat resembles beefsteak cuisine (Ólafsdóttir pers. comm.). Check out the following link for whale recipes from Iceland or click here for other recipes from other countries.

Faroe Islands

Fin whales were only caught in the Faroe Islands after the late 1800s, when whaling stations were also developed. There were seven stations in total, the first (Gjanoyri) opening in 1894.

After flensing at the whaling station, the blubber was rendered to oil and used for margarine production. Skeletons and entrails were thrown back to the sea. The meat was used for human consumption, either boiled or fried. The tongue stock, veined with fat, was also used but had to be salted for some days. It was then boiled and served with horseradish cream sauce (Bloch pers. comm.).

Greenland

The three major products – meat, blubber and the throat pleats (ventral grooves) – constitute the primary parts of the whale eaten in Greenland. The other parts of the whale that are considered edible varies between regions and villages, particularly with respect to the internal organs (e.g. liver, heart and kidneys) and tongue, which can vary from being considered a delicacy to being deemed inedible. Sometimes, the captain retains the heart and kidney for use by his family. The flukes are also considered a delicacy in Illulissat.

The intestines are generally not eaten, but in some places (e.g. Sisimiut) the tongue and intestines may be used to feed dog teams. Greenlandic cooking books offer many recipes for whale meat, but often do not distinguish between whale species.

Norway

The hunting of fin whales and other rorquals, using steam powered vessels and exploding harpoons, was pioneered by Norway in the latter half of the 19th century. The main product from the hunt was always the blubber, which was rendered into oil at shore stations. The oil in turn was used as lamp oil and in the manufacture of soap and margarine. Most of the production of the Norwegian hunt was exported to other markets. At some shore stations, the flayed carcass of the whale was cooked, then dried, to make a rich fertiliser.

The meat of the fin whale has never been successfully marketed within Norway. However, some export of fin whale meat to Japan took place in the 20th century.

HUNTING METHODS

The text under this item is extracted and slightly modified from the report of the NAMMCO Expert Group Meeting on Assessment of Whale Killing Data (NAMMCO 2010b). Information on the Greenlandic hunts has also been extracted from the Report on Greenlandic Conversion Factors (IWC 2010b).

People’s right to hunt and utilise marine mammals is a firmly established principle in NAMMCO and hunting conditions and techniques have always been priority issues. Embedded in this right is also an obligation to conduct the hunt in a sustainable way and in such a way that animal suffering is minimised.

Hunting methods depend on the species (size, behaviour) and the habitat. In the North Atlantic, fin whales are currently hunted by two NAMMCO countries – Greenland and Iceland. For animal welfare reasons, it is important to achieve a rapid and efficient kill of the targeted whale. This means that both unnecessary suffering and the risk of losing the animal should be minimised. Ideally, the animal should become instantly unconscious and insensitive to pain.

Hunting methods for fin whales differ between Greenland and Iceland, but harpoon guns with explosive penthrite grenades are used in both countries.

Harpoon guns as hunting method

A harpoon cannon rigged onto the deck of a boat is used to fire a harpoon equipped with an explosive grenade into the body of the whale. The triggering cord is a string with one end attached to the detonator and the other end attached to a small hook. This hook anchors itself to the skin of the whale and as the harpoon penetrates the body of the whale, the triggering cord unfolds until it tenses and initiates the detonation of the grenade. In this way, the grenade explodes deep inside the body of the whale.

The harpoon is attached to a forerunner, which in turn is attached to a winch on the boat. This kind of whaling requires a boat large enough to carry a harpoon cannon. In Greenland, the minimum boat length required for installing a harpoon cannon is 10 m. At the other end of the spectrum, 100 m long ocean-going vessels are and have been used by Japan for whaling offshore and in the Antarctic.

Iceland

Fin whale hunting is conducted from medium-sized boats that are exclusively used for whale hunting but are not equipped for flensing the whale nor processing and storing meat and blubber. The hunting grounds are within Iceland’s 200 miles exclusive economic zone (EEZ) and the whales are towed to the Icelandic land station for flensing and processing.

The boats are equipped with strong winches for hauling the whales, which can load up to 30 tonnes. The hunting weapon used is a 90 mm harpoon gun with 4-claws. Prior to 2009, cast iron grenades filled with black powder (500 g) together with (from 1986 on) a modified penthrite grenade with 100g of penthrite fuse were used to kill the whales.

When Iceland resumed fin whale hunting in 2009, a prototype of a modified penthrite grenade with 100 g of pressed penthrite was developed and tested. This prototype, which was made of aluminium, was lighter than the previous grenades. However, it showed some weaknesses in the head design and the trigger hooks and was replaced by a new prototype penthrite grenade made of steel (Proto 2) in 2010. The back-up weapon is reshooting with a harpoon grenade.

Greenland

Types of flensing sites in Greenland: Top ‘island’ – Saqqap Avannaatunga near Sisimiut; Middle: slope with winches in sheltered inlet – Oqaatsut near Ilulissat; Bottom: slope in sheltered inlet – Assaqutak near Sisimiut

(IWC, 2010b)

Fin whales are caught in West Greenland, south of Uummannaq. It is done by either two boats each of a minimum length of 9 m working together, or by one boat of a minimum length of 11 m. After the whale is caught, the boats return to land for flensing. Each boat is equipped with one certified harpoon cannon, which is checked every other year.

Fin whales are hunted with 50 mm Kongsberg harpoon guns using harpoons equipped with the Norwegian penthrite grenade (Grenade-99) charged with 30 g of pressed penthrite. The trigger rope for the fin whale grenade is 110 cm (longer than that used for minke whales which is 45 cm) and it detonates the grenade 130-140 cm after penetration into the whale body (65 cm for the minke whale). The secondary (back up) weapon is the same as the primary weapon. The gunners shoot into the heart and lung regions by aiming at the area in front of the pectoral fins. During the years 2001 – 2008 it was reported that 20 % of the whales died instantaneously or within 1 minute and that 40 – 50 % died within 5 minutes.

PAST AND CURRENT CATCHES

Exploitation in the North Atlantic before the 1986 temporary moratorium on whaling

Being much faster than any other whale species, fin whales could not be hunted to any great extent until fast catcher boats (steam ships) and explosive harpoons had been developed as part of commercial whaling in the late 1800s in Norway. These inventions made catches possible and fin whales became heavily exploited in the modern whaling era after this.

Fin whale catches increased throughout the early 1900s and reached over 30,000 per year worldwide in the late 1950s and early 1960s (Tønnessen and Johnsen 1982). Although the vast majority of these catches were taken in the Southern Hemisphere, fin whales were also considerably depleted in the north. Whaling was banned in Norway in 1904, mainly because of a belief by fishermen that whales herded herring to the coast, thereby making the fish accessible to them. By this time, however, the stocks off Northern Norway were already severely depleted (Tønnessen and Johnsen 1982).

Initial phase

Norwegian companies established whaling stations in many areas of the North Atlantic after depleting whale stocks off their own coast (Tønnessen and Johnsen 1982). Whaling stations were established in Iceland, Spitsbergen, the Faroe Islands, the Shetland Islands, the Hebrides and Ireland as well as in Newfoundland. In all of these areas, the same scenario was repeated: a whaling station was established, followed by good catches and rapid expansion. This was in turn followed by declining catches until, eventually, whaling became unprofitable. In some areas, this process took as little as 10 years. In most areas, the initial phase of whaling was over by 1920 (Tønnessen and Johnsen 1982).

Harvesting was especially heavy around Iceland and led to a noticeable decline in catch rates for fin whales there between 1901 and 1915. (IWC 1989, NAMMCO 2000a,b). The situation was serious enough that it led to Iceland imposing a moratorium on whaling in Icelandic waters in 1915, the first whaling moratorium ever.

1935 and onwards

When whaling resumed in 1935 west of Iceland, the stock appeared to have recovered there, possibly through both natural population growth and immigration from other areas (NAMMCO 2000a,b). Fin whaling resumed in most areas after World War 2. In Norway and the Faroe Islands, whaling continued until 1971 and 1984 respectively, when declining or variable catches and low prices made the operations unprofitable.

In 1986, the IWC instituted a temporary moratorium on commercial whaling. Iceland, however, continued to catch fin whales in the period 1986-1989, as part of a scientific research programme.

Exploitation in the North Atlantic after the 1986 moratorium

Greenland continued hunting fin whales from West Greenland, under an IWC “aboriginal subsistence whaling” quota of 19 fin whales per year (total quota, i.e., including landed and struck-and-lost whales). Recent harvests have been lower than the quota level (Table below).

In 2002 Iceland rejoined the IWC but with a formal objection to the moratorium, which meant it was not legally bound by it. In 2006, Iceland then resumed hunting fin whales, with a catch of 7 in 2006, and then oscillating between 0 and 155 since that time (Table below). No other country in the world presently has a directed harvest of fin whales. Japan started a scientific catch of the species in the Antarctic in 2005, but discontinued this when they left the IWC in 2019.

Catches in NAMMCO member countries since 1992

| Country | Species (common name) | Species (scientific name) | Year or Season | Area or Stock | Catch Total | Quota (if applicable) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greenland | Fin whale | Balaenoptera physalus | 2023 | West | 3 | 19 |

| Greenland | Fin whale | Balaenoptera physalus | 2022 | West | 3 | 19 |

| Greenland | Fin whale | Balaenoptera physalus | 2021 | West | 2 | 19 |

| Greenland | Fin whale | Balaenoptera physalus | 2020 | West | 3 | 19 |

| Greenland | Fin whale | Balaenoptera physalus | 2019 | West | 8 | 19 |

| Greenland | Fin whale | Balaenoptera physalus | 2018 | West | 7 | 19 |

| Greenland | Fin whale | Balaenoptera physalus | 2017 | West | 8 | 19 |

| Greenland | Fin whale | Balaenoptera physalus | 2016 | West | 10 | 19 |

| Greenland | Fin whale | Balaenoptera physalus | 2015 | West | 12 | 19 |

| Greenland | Fin whale | Balaenoptera physalus | 2014 | West | 12 | 19 |

| Greenland | Fin whale | Balaenoptera physalus | 2013 | West | 9 | 19 |

| Greenland | Fin whale | Balaenoptera physalus | 2012 | West | 5 | 10 |

| Greenland | Fin whale | Balaenoptera physalus | 2011 | West | 5 | 10 |

| Greenland | Fin whale | Balaenoptera physalus | 2010 | West | 6 | 10 |

| Greenland | Fin whale | Balaenoptera physalus | 2009 | West | 10 | 19 |

| Greenland | Fin whale | Balaenoptera physalus | 2008 | West | 14 | 19 |

| Greenland | Fin whale | Balaenoptera physalus | 2007 | West | 12 | 10 |

| Greenland | Fin whale | Balaenoptera physalus | 2006 | West | 10 | 10 |

| Greenland | Fin whale | Balaenoptera physalus | 2005 | West | 13 | 19 |

| Greenland | Fin whale | Balaenoptera physalus | 2004 | West | 13 | 19 |

| Greenland | Fin whale | Balaenoptera physalus | 2003 | West | 9 | 19 |

| Greenland | Fin whale | Balaenoptera physalus | 2002 | West | 13 | 19 |

| Greenland | Fin whale | Balaenoptera physalus | 2001 | West | 8 | 19 |

| Greenland | Fin whale | Balaenoptera physalus | 2000 | West | 7 | 19 |

| Greenland | Fin whale | Balaenoptera physalus | 1999 | West | 9 | 19 |

| Greenland | Fin whale | Balaenoptera physalus | 1998 | West | 11 | 19 |

| Greenland | Fin whale | Balaenoptera physalus | 1997 | West | 13 | 19 |

| Greenland | Fin whale | Balaenoptera physalus | 1996 | West | 19 | 19 |

| Greenland | Fin whale | Balaenoptera physalus | 1995 | West | 12 | 19 |

| Greenland | Fin whale | Balaenoptera physalus | 1994 | West | 22 | 19 |

| Greenland | Fin whale | Balaenoptera physalus | 1993 | West | 14 | 21 |

| Greenland | Fin whale | Balaenoptera physalus | 1992 | West | 22 | 21 |

| Iceland | Fin whale | Balaenoptera physalus | 2023 | East Greenland - West Iceland | 24 | 193 |

| Iceland | Fin whale | Balaenoptera physalus | 2022 | East Greenland - West Iceland | 148 | 193 |

| Iceland | Fin whale | Balaenoptera physalus | 2021 | East Greenland - West Iceland | 0 | 193 |

| Iceland | Fin whale | Balaenoptera physalus | 2020 | East Greenland - West Iceland | 0 | 161 |

| Iceland | Fin whale | Balaenoptera physalus | 2019 | Iceland | 0 | 161 |

| Iceland | Fin whale | Balaenoptera physalus | 2018 | Iceland | 146 | 161 |

| Iceland | Fin whale | Balaenoptera physalus | 2017 | Iceland | 0 | 175 |

| Iceland | Fin whale | Balaenoptera physalus | 2016 | Iceland | 0 | 146 |

| Iceland | Fin whale | Balaenoptera physalus | 2015 | Iceland | 155 | 171 |

| Iceland | Fin whale | Balaenoptera physalus | 2014 | Iceland | 137 | 154 |

| Iceland | Fin whale | Balaenoptera physalus | 2013 | Iceland | 134 | 154 |

| Iceland | Fin whale | Balaenoptera physalus | 2012 | Iceland | 0 | 154 |

| Iceland | Fin whale | Balaenoptera physalus | 2011 | Iceland | 0 | 154 |

| Iceland | Fin whale | Balaenoptera physalus | 2010 | Iceland | 148 | 150 |

| Iceland | Fin whale | Balaenoptera physalus | 2009 | Iceland | 125 | 150 |

| Iceland | Fin whale | Balaenoptera physalus | 2008 | Iceland | 0 | |

| Iceland | Fin whale | Balaenoptera physalus | 2007 | Iceland | 0 | |

| Iceland | Fin whale | Balaenoptera physalus | 2006 | Iceland (EGI) | 7 | |

| Iceland | Fin whale | Balaenoptera physalus | 1992-2005 | Iceland | 0 | |

This database of reported catches is searchable, meaning you can filter the information by for instance country, species or area. It is also possible to sort it by the different columns, in ascending or descending order, by clicking the column you want to sort by and the associated arrows for the order. By default, 30 entries are shown, but this can be changed in the drop-down menu, where you can decide to show up to 100 entries per page.

Carry-over from previous years are included in the quota numbers, where applicable.

You can find the full catch database with all species here.

For any questions regarding the catch database, please contact the Secretariat at nammco-sec@nammco.no.

Other Human Impacts

Anthropogenic activities that may affect fin whales can be divided into two main categories: habitat degradation and oceanographic changes through phenomena such as climate change.

HABITAT DEGRADATION

Knowledge about fin whale habitat use is limited and it is therefore difficult to assess the impact that habitat degradation may represent for the species. A range of anthropogenic activities has the potential to degrade habitat important to fin whale survival though, and may occur both when whales are present or absent. These types of impacts include:

- entanglement (e.g. in marine debris, fishing gear, etc)

- physical injury and death from vessel collisions (service corridors and shipping lanes)

- acoustic pollution with disturbance from low-frequency noise (vessel, seismic survey, military activities)

- changing water quality and pollution (e.g. runoff from agriculture, oil spills)

- prey depletion due to over-harvesting

- human harassment through whale watching programmes

Entanglements and ship strikes

Fin whales, Faroese stamps, Postverk Føroya 2001

Fin whales commonly lunge feed at or near the surface, which makes them vulnerable to ship strikes and entanglements. They are one of the more commonly recorded species of large whale reported as being hit by vessels worldwide (Laist et al. 2001, Jensen and Silber 2003). They are also occasionally caught in fishing gear as incidental catch or by-catch.

In the NAMMCO area, however, entanglements and ship strikes appear as a very minimal threat for fin whales. Over the period 2000–2018 (National Progress Reports, NAMMCO 2001–2010, and 2016-2018 ) only two by-catches and one ship strike have been reported for fin whales. One fin whale was entangled off West Greenland in ropes used in connection with crab traps (Anonymous 2004), and another in 2016, while the likely strike was caused by a ferry off Iceland (Ólafsdóttir pers. comm.).

Reporting of large cetacean by-catch is only mandatory in Greenland and Iceland, but these events get much local attention, probably because they are very rare. The authorities become aware of most cases, if not all, through different channels, such as direct reports to museums and marine institutes or articles in newspapers. In the NAMMCO area, fin whales are mainly distributed offshore, with little overlap with the main fishing areas, which helps explains the low risk of entanglement.

Acoustic Pollution

Noise from seismic exploration, military activities and shipping could affect fin whales directly or indirectly by interfering with their communication, however the effects are not well studied (IWC 2005). Since fin whales use low frequency sounds to call to females, human interruption through sound waves, such as military sonar and seismic surveys can disrupt the signal sent to the females. This has the potential to interfere with mating by preventing mates from meeting, with a consequential reduction in birth rates in populations (Croll et al. 2002).

Oceanographic Changes

The exact implications of climate change on oceanographic conditions and processes are still emerging, as are their subsequent implications for whales. Reduced productivity of some ecosystems and unpredictable weather events caused by altered ocean water temperatures, changing ocean currents, rising sea levels and reductions in sea ice are predicted as possible consequences of climate change.

Fin whale habitat areas might be affected directly through changes in food availability caused by decreased productivity and/or changed patterns in prey distribution and availability (e.g. Williams et al. 2013). Also, if ocean currents and water temperature influence whale migration, feeding, breeding, and/or calving site selection, any changes in these factors could render currently used habitats unsuitable.

RESEARCH PROJECTS IN THE WILD

Fin whales, which are largely pelagic and rarely seen in groups near coasts in the NAMMCO area, are difficult to study in the wild. Except for sightings surveys dedicated to large baleen whales, where also fin whales are targeted, there are only a few research projects dedicated to living fin whales. Incidental fin whale sightings are recorded in opportunistic sighting databases in the four NAMMCO countries.

Satellite tagging of fin whales have been attempted with more or less success in most countries: the Faroe Islands (Mikkelsen et al. 2007), Greenland (Heide-Jørgensen et al. 2003) and Iceland (Watkins et al. 1984, 1996). In the beginning there was limited success in tagging fin whales, however the methodology and the tags have greatly improved over time and whales are now tagged successfully (e.g. in Greenland and Norway).

Greenland

Low numbers of fin whales are tagged with satellite transmitters every year in West Greenland by the Greenland Institute of Marine Resources. The main purpose is to use dive data collected from the transmitters to correct visual aerial surveys for the fraction of whales that are submerged during the surveys. The transmission period for effectively deployed tags has been about 5 weeks. This is not long enough to show where the whales go in winter but does provide enough data to show their use of West Greenland and to provide dive data. Fin whales were again one of the target species for telemetry studies in 2019 (National Progress Report Greenland 2019).

New light has been shed on the migratory pattern and habitat use of fin whales in the Davis Strait, between Greenland and Canada through acoustic monitoring. The whales’ acoustic activity has been monitored using three bottom-moored acoustic recorders over a 2-year period. This work showed that the whales are present in the area from June to December and thus migrate south much later than previously believed (Simon et al. 2010), see also the section on Migration for more details).

Iceland

The University of Iceland Research Center in Húsavik and the Húsavík Whale Museum conduct a collaborative photo-identification project mostly focusing on blue and humpback whales as well as white-sided dolphins, the species most commonly observed in Skjálfandi Bay. Although not as commonly observed in this bay, the project also includes fin whales.

Norway

During different field projects, the Norwegian Institute of Marine Research (IMR) collects biopsy samples and photo-identifications of whales and dolphins, and when an opportunity arises, also fin whales (Grønvik et al. 2009, 2010). Biopsies have been collected in the Norwegian Sea and the Barents Sea. The last major biopsy collection from fin whales was off Spitsbergen in 2008. Two samples were also taken in 2012 from the same area. All the fin whale samples are analysed at P. Palsbøll’s laboratory at the University of Groningen.

The Norwegian Polar Institute also collects biopsies from fin whales in the Svalbard area to study genetics, diet and pollution issues. 6 biopsies were collected in 2017, 1 in 2019, and 12 in 2020 (National Progress Report Norway 2017, 2019, 2020).

The Norwegian Polar Institute and the IMR also cooperate in an ongoing project for satellite tagging of fin whales in the Svalbard area. In 2018, 5 fin whales were tagged (National Progress Report Norway, 2018) and 25 in 2019 (National Progress Report Norway 2019). The 2019 tagging was carried out by helicopter on the west coast of Svalbard, with Polarsyssel serving as the base ship.

The IMR also investigates the spatial associations between rorquals (fin whales included) and their prey, based on ecosystem and fish monitoring surveys performed during summers 2003 to 2017 in Norwegian and adjacent waters. Some results can be found in Skern-Mauritsen et al. (2011) and Nøttestad et al (2015).

RESEARCH PROJECTS CONNECTED TO CATCHES

Iceland

Iceland resumed commercial whaling in 2006, and the Icelandic Marine and Freshwater Research Institute (MFRI) took this as an opportunity to initiate research. Fin whale research conducted at the whaling station in Hvalfjörður is wide-ranging and includes work on age, life history parameters (growth and reproduction), feeding ecology, energetics, pollutants, genetics, hybridisation, anatomy, and physiology of fin whales from the whaling grounds west of Iceland (National Progress Report Iceland 2019). Some of this research is used to compare current data with information obtained prior to 1990 (Víkingsson 1990, 1995, 1997, Víkingsson et al. 1988, Lockyer and Sigurjònsson 1992).

Iceland collected several hundred samples between 2006 and 2015 from commercial catches and plans to collect new samples from any future catches. Although there were no catches in 2016 and 2017, and no hunt in 2019, analysis of the samples remains ongoing.

International cooperation

There is an international project that is of special interest due to the observed changes in the ecosystem in Icelandic waters and increased abundance of fin whales in the area in recent years. The MFRI has established cooperation with several foreign research institutes including the University of Barcelona, University of British Columbia, University of California and Greenland Institute of Natural Resources.

The team from the University of British Columbia, for example, has focused on the analysis of anatomical features related to engulfment feeding and diving in fin whales, including many structures in the head and thorax including diaphragm, arteries, nerves and muscles in the ventral groove blubber and tongue, esophagus, pharynx, lung and baleen. The aim of this work is two-fold:

- To understand how rorqual whales have evolved the capacity to engulf extremely large volumes of water containing prey, filter the prey items from the water, and swallow the prey rapidly with total protection of the airway.

- To explore mechanisms that protect against adverse effects of rapid descent in the ocean that must cause transient pressure gradients in the thorax, vascular system, and lungs.

Analysis of the samples and the data collected through all these projects is in progress (Nielsen et al. 2012, Pyenson et al. 2012, Shadwick et al. 2013, Olsen et al. 2014, Vogl et al. 2015).

Cooperation between the MFRI and the University of Barcelona has been wide ranging and analysis of pollutant levels. focused on analysis of stable isotopes as indicators for feeding ecology, pollution and population structure (e.g. Arregui et al. 2018, Garcia-Garin et al. 2020, 2021, Garcia-Vernet et al. 2018, 2021a, 2021b, Gauffier et al. 2020).

Other projects

Research led by the National University Hospital of Iceland focuses on the structure and function of the inner ear of fin whales (National Progress Report Iceland 2018). Some of the inner ear samples have been submitted to a large international study on the effects of acoustic pollution on the hearing of cetaceans.

Anonym. (2004). Greenland Progress Report on Marine Mammals 2002, pp. 319-322. In: NAMMCO Annual Report 2003. NAMMCO, Tromsø, Norway. https://nammco.no/topics/annual-reports/

Arregui, M., Borrell, A., Víkingsson, G. A., Ólafsdóttir, D., & Aguilar, A. (2018). Stable isotope analysis of fecal material provides insight into the diet of fin whales. Marine Mammal Science, 34(4), 1059–1069. https://doi.org/10.1111/mms.12504

Árnason, Ú, Spilliaert, R., Pálsdóttir, Á.K. and Árnason, A. (1991). Molecular identification of hybrids between the two largest whale species, the blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus) and the fin whale (B. physalus). Hereditas, 115, 183-189. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1601-5223.1991.tb03554.x

Bérubé, M. and Aguilar, A. 1998. A new hybrid between a blue whale, (Balaenoptera musculus), and a fin whale, (B. physalus): Frequency and implications of hybridization. Marine Mammal Science, 14(1), 82-98. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-7692.1998.tb00692.x

Bérubé, M., Aguilar, A., Dendanto, D., Larsen, F., Notarbartolo di Sciara, G., Sears, R., Sigurjónsson, J., Urban-R., J. and Palsbøll, P.J. (1998). Population genetic structure of North Atlantic, Mediterranean Sea and Sea of Cortez fin whales, Balaenoptera physalus (Linnaeus 1758): analysis of mitochondrial and nuclear loci. Molecular Ecology, 7, 585-601. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-294x.1998.00359.x

Bioacoustics Research Program, Cornell Lab of Ornithology. (2010). “Finback whale vocalizations”. http://www.birds.cornell.edu/brp/listen-to-project-sounds/fin-whales. Retrieved 11-27- 2014

Bloch, D. and Joensen, J.S. (1985). Faroese progress report on cetacean research 1983. Report of the International Whaling Commission, 35, 165-166.

Bloch, D. and Allison, C. (2007). The North Atlantic catch and cpue of fin whales, 1868-1984, taken by Norway, the Faroes, Shetland, the Hebrides, Ireland and Greenland. SC/14/FW/15 for the NAMMCO Scientific Committee.

Cipriano, F. and Palumbi, S.R. (1999). Genetic tracking of a protected whale. Nature, 397, 307-308. https://doi.org/10.1038/16823

Clark, C. W. (1995). Application of US Navy underwater hydrophone arrays for scientific research on whales. Reports of the International Whaling Commission, 45, 210-212.

Cooke, J.G. (2018). Balaenoptera physalus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018: e.T2478A50349982. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T2478A50349982.en

Croll, D.A., Clark, C.W., Acevedo, A., Flores, S., Gedamke, J. and Urban, J. (2002). Only male fin whales sing loud songs. Nature, 417(6891), 809. https://doi.org/10.1038/417809a

Daníelsdóttir, A.K., Duke E.J., Joyce P. and Árnason A. (1991). Preliminary studies on the genetic variation at enzyme loci in fin whales (Balaenoptera physalus) and sei whales (Balaenoptera borealis) from North- Eastern Atlantic. Reports of the International Whaling Commission (special issue 13), 115-124.

Daníelsdóttir, A.K., Sigurjónsson, J., Mitchell, E. and Árnason, A. (1992). Report on a pilot study of genetic variation in skin samples of North Atlantic fin whales (Balaenoptera physalus). Paper SC/44/NAB16 presented to the IWC Scientific Committee, June 1992 (unpublished). pp. 8.

Donovan, G.P. (1991). A review of IWC stock boundaries. In Hoelzel, A.R. (ed.) Genetic ecology of whales and dolphins (pp. 39-68). Reports of the International Whaling Commission (Special Issue 13).

Gambell, R. (1985). Fin whale Balaenoptera physalus. In Ridgway, S.H. and R. Harrison (eds.), Handbook of Marine Mammals Vol. 3: The Sirenians and Baleen Whales (p. 171-192).

Garcia-Garin, O., Aguilar, A., Vighi, M., Víkingsson, G. A., Chosson, V., & Borrell, A. (2021). Ingestion of synthetic particles by fin whales feeding off western Iceland in summer. Chemosphere, 279, 130564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.130564

Garcia-Garin, O., Sala, B., Aguilar, A., Vighi, M., Víkingsson, G. A., Chosson, V., Eljarrat, E., & Borrell, A. (2020). Organophosphate contaminants in North Atlantic fin whales. Science of The Total Environment, 137768. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.137768

García-Vernet, R., Borrell, A., Víkingsson, G., Halldórsson, S. D., & Aguilar, A. (2021a). Ecological niche partitioning between baleen whales inhabiting Icelandic waters. Progress in Oceanography, 199, 102690. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pocean.2021.102690

García‐Vernet, R., Sant, P., Víkingsson, G., Borrell, A., & Aguilar, A. (2018). Are stable isotope ratios and oscillations consistent in all baleen plates along the filtering apparatus? Validation of an increasingly used methodology. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry, 32(15), 1257–1262. DOI: 10.1002/rcm.8169

García‐Vernet, R., Martín, B., Peinado, M.A., Víkingsson, G., Riutort, M., Aguilar, A., (2021b). CpG methylation frequency of TET2, GRIA2, and CDKN2A genes in the North Atlantic fin whale varies with age and between populations. Marine Mammal Science. DOI: 10.1111/mms.12808

Gauffier, P., Borrell, A., Silva, M. A., Víkingsson, G., López, A., Giménez, J., Colaço, A., Halldórsson, S. D., Vighi, M., Prieto, R., de Stephanis, R., & Aguilar, A. (2020). Wait your turn, North Atlantic fin whales share a common feeding ground sequentially. Marine Environmental Research, 104884. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marenvres.2020.104884

Gauffier, P. 2023. Balaenoptera physalus (Europe assessment). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2023: e.T2478A213291870. Accessed on 19 December 2023.

Goldbogen. J.A. (2010). The Ultimate Mouthful: Lunge Feeding in Rorqual Whales. American Scientist, 98(2), 124. https://doi.org/10.1511/2010.83.124

Greenland. (2012). White paper on the management and utilization of large whales in Greenland. https://nammco.no/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/greenland-whitepaper-on-whaling-2018-iwc-final.pd_.pdf

Grønvik, S., Haug, T. and Øien, N. (2009). Norwegian Progress Report on Marine Mammals 2007-2008. In: NAMMCO Annual Report 2007-2008. NAMMCO, Tromsø, Norway. pp. 337-377. https://nammco.no/topics/annual-reports/

Grønvik, S., Haug, T. and Øien, N. (2010). Norwegian Progress Report on Marine Mammals 2009. In: NAMMCO Annual Report 2009. NAMMCO, Tromsø, Norway, pp. 489-512. https://nammco.no/topics/annual-reports/

Hammond, P. S., Lacey, C., Gilles, A., Viquerat, S., Boerjesson, P., Herr, H., … and Scheidat, M. (2017). Estimates of cetacean abundance in European Atlantic waters in summer 2016 from the SCANS-III aerial and shipboard surveys. Wageningen Marine Research. https://synergy.st-andrews.ac.uk/scans3/files/2017/04/SCANS-III-design-based-estimates-2017-04-28-final.pdf

Hansen, R.G., Boye, T.K., Larsen, R.S., Nielsen, N.H., Tervo, O., Nielsen, R.D., Rasmussen, M.H., Sinding, M.H.S. & Heide-Jørgensen, M.P. 2018. Abundance of whales in West and East Greenland in summer 2015. NAMMCO Scientific Publications, 11. https://doi.org/10.7557/3.4689