Beluga

Last updated: February 2022, reviewed by NAMMCO’s Scientific Committee

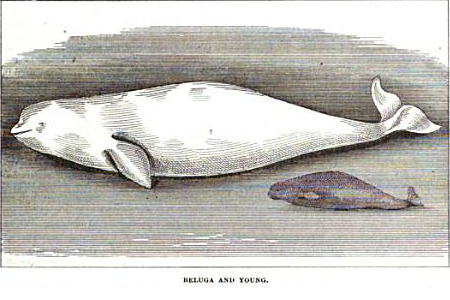

The beluga (or white whale) is a medium-sized toothed whale. They have stout bodies, flexible necks, and a disproportionately small head with a well-defined beak and a prominent forehead bulge or “melon”. They have short but broad paddle-shaped flippers, no dorsal fin, a narrow ridged back and a broad tail fluke with a deeply notched centre. Adult beluga whales grow to lengths of 3.5-5.5 m and can weigh up to 1,500 kg while males grow slightly larger than females. Newborns are brown or slate-grey in colour and average 1.6 m in length and 78 kg in weight. They become bluish-grey as they mature, then progressively lighten in colour, fading to pure white after 14 years of age for females and 18 years for males (O’Corry-Crowe 2018).

ABUNDANCE

Across the Arctic there are estimated to be at least 180,000 belugas.

DISTRIBUTION

Belugas are found in Arctic and sub-Arctic waters, generally in areas that are seasonally ice-covered. In the North Atlantic they are found in the northern waters of the US (Alaska), Canada, Greenland, Norway and Russia.

RELATION TO HUMANS

Belugas are hunted for food throughout their range, except for Svalbard where they are protected. Past commercial harvesting reduced numbers in some areas.

CONSERVATION AND MANAGEMENT

The Eastern High Arctic stock of belugas is a shared stock between Greenland and Canada and therefore subject to an international management regime under the Joint Commission for the Conservation and Management of Narwhal and Beluga (JCNB). The JCNB and NAMMCO hold Joint Scientific Working Group meetings to provide scientific advice to the JCNB and NAMMCO.

In West Greenland, after hunting quotas were introduced, harvests have been reduced and the stock is thought to be recovering from previous overhunting.

The other beluga stock in the NAMMCO area is the Svalbard stock. These belugas are protected.

In the most recent regional assessment (2023) for Europe the species is listed as ‘Vulnerable’ on the IUCN Red List, as well as ‘Vulnerable’ on Greenlandic national red list, and ‘Endangered’ on the Norwegian national red list.

Size

Adult beluga whales grow to lengths of 3.5-5.5m and can weigh up to 1,500 kg. Males grow slightly larger (up to 25% longer) than females (O’Corry-Crowe 2018).

Productivity

One calf every 2-3 years from 9-12 years of age.

Lifespan

up to 80 years

Migration

Throughout their range belugas inhabit cold Arctic waters, living amongst pack ice, in leads and polynyas in winter and migrating to shallow bays and estuaries of large northern rivers in the summer.

Feeding

Mainly fish, particularly polar cod (Boreogadus saida) and Arctic cod (Actogadus glacialis). Also northern shrimp (Pandalus borealis) and squid in some areas and times.

General Characteristics

Beluga whales have stout bodies, flexible necks and a disproportionately small head with a well defined beak and a prominent forehead bulge or “melon”. They have short but broad paddle-shaped flippers, no dorsal fin, a narrow ridged back and a broad tail fluke with a deeply notched centre. The generic name “delphinapterus”, meaning “dolphin-without-a-wing” reflects the absence of a dorsal fin.

Life History and Ecology

© Calvin L Hooper

Adult beluga whales grow to lengths of 3.5–5.5 m and can weigh up to 1,500 kg while males grow slightly larger (up to 25% longer) than females (O’Corry-Crowe 2018). Newborns are brown or slate-grey in colour and average 1.6 m in length and 78 kg in weight. They become bluish-grey as they mature, then progressively lighten in colour, fading to pure white after 14 years of age for females and 18 year for males (O’Corry-Crowe 2018). Most females reach sexual maturity while still light grey, while males turn completely white before. Additionally, older males have a marked upward curve at the tip of their flippers.

Belugas mate in late winter to early spring, and calving occurs a little over a year later (14-14.5 months)(O’Corry-Crowe 2018). Calving for belugas in the Canadian High Arctic population occurs mainly during early July to early August, although calves have been reported there as early as 31 May, and as early as late March off west Greenland (Koski et al. 2002). Recent research has shown that belugas may have lifespans of 80 years or more (Stewart et al. 2006).

Feeding

Polar cod (Boreogadus saida) and Arctic cod (Actogadus glacialis) were found to contribute more than any other item to the diet of beluga in the Upernavik area in Greenland (Heide-Jørgensen & Teilmann 1994). Moreover, polar cod was also found to be the principle food item for Canadian High Arctic and Svalbard beluga (Koski et al. 2002, Dahl et al. 2000). On the other hand, squid beaks were commonly found in beluga stomachs from western Greenland. Other prey items found were redfish (Sebastes marinus), halibut (Reinhardtius hippoglossoides) and northern shrimp (Pandalus borealis) (Heide-Jørgensen & Teilmann 1994). Polar cod was also found to be the main prey item for beluga in Russian waters, with various whitefish (Coregonidae) contributing to the diet in summer (Boltunov & Belikov 2002).

Capelin

Capelin (Mallotus villosus) are an important food source for beluga in the St. Lawrence River and also in Hudson Bay (Kingsley 2002). Other important food items are sand-lance (Ammodytes spp.), Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua), tomcod (Microgadus tomcod), decapod and amphipod crustaceans as well as polychaete worms.

Young beluga begin feeding on fish and invertebrates after their first year, but may continue to take milk from their mothers during their second year of life (Heide-Jørgensen & Teilmann 1994). As the animals grow, they are able to take larger food items, and gradually switch from benthic to more pelagic foraging.

Predation

Recent reductions in Arctic sea ice have made the area more accessible to the killer whale, which is a major predator of belugas. Researchers have observed increasing killer whale sightings across numerous regions in the eastern Canadian Arctic (Higdon & Ferguson 2009). This may result in an increase in predation pressure and a concomitant decrease in survival in some beluga populations (Ferguson et al. 2010). You can read more about killer whale predation on belugas here.

Polar bears are also predating on beluga whales – particularly in Lancaster Sound, Baffin Bay and the Gulf of Boothia beluga can make up 25-33% of polar bear’s food intake (Thiemann et al. 2008). You can watch a video of a polar bear catching beluga whales that have been entrapped in ice below.

DID YOU KNOW?

Thousands of Belugas Were Once Rescued by Classical Music and an Icebreaker

In 1984, a large group of belugas were trapped for several months in the ice of Senyavin Strait in the Bering Sea. The white whales had followed a shoal of fish into the strait when it was open but as the conditions changed and closed in around them, found themselves trapped in ice too thick to breach and too vast to negotiate with a single breath.

In an unusual effort to save them, an ice-breaker was summoned to clear a path through the ice. However, the whales were so exhausted and weakened from their months of entrapment, and frightened by the noise of the icebreaker, that they refused to follow the ship before the ice closed up behind it again.

One crew member then had the bright idea to try playing different types of music to them. To the crew’s delight, the pod of belugas responded to the classical music and began to slowly follow the ship out to sea and back to freedom as it was playing.

©Doug Allan

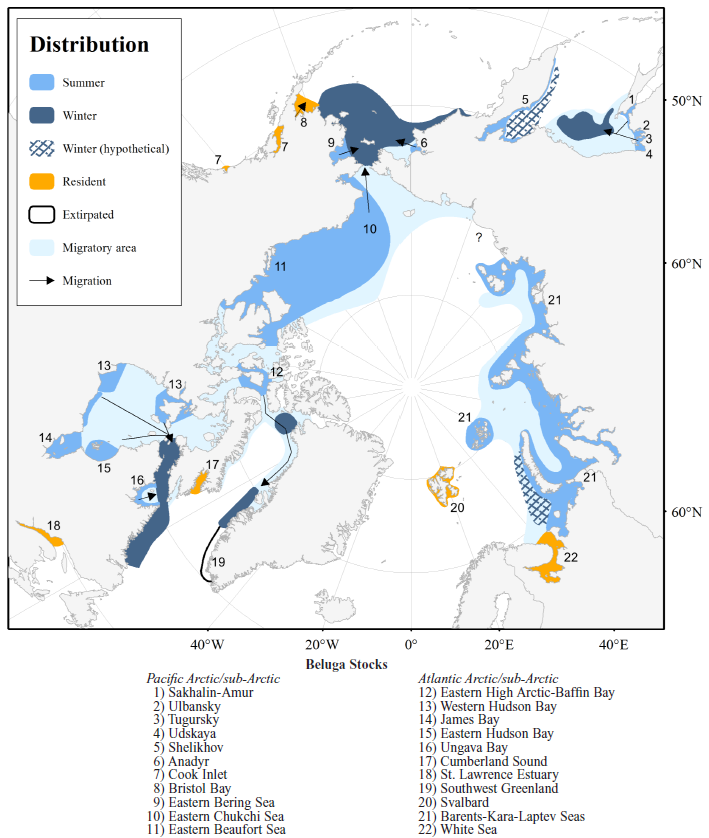

DISTRIBUTION

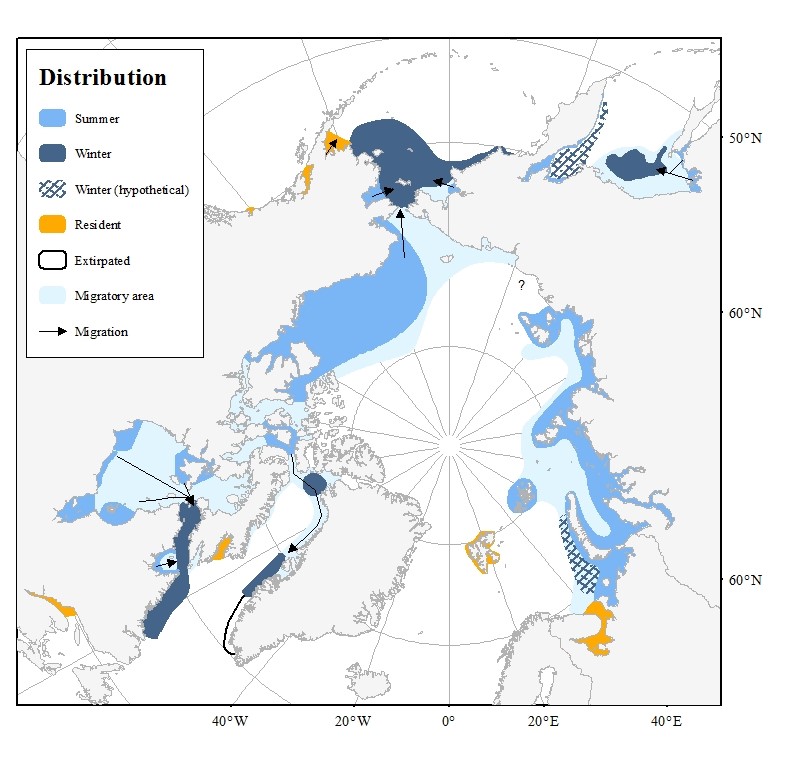

Beluga whales have a discontinuous circumpolar distribution throughout the Arctic and sub-Arctic. They typically exhibit some level of site fidelity, inhabiting the same summering and wintering areas year after year (O’Corry-Crowe et al. 1997; Tourgeon et al. 2012). Most belugas are migratory, however, some of the smaller populations appear to be resident year-round in specific regions and do not undertake long-distance migrations (e.g. Cook Inlet, Cumberland Sound, St Lawrence Estuary).

HABITAT

© Vicki Beaver, Alaska Fisheries Science Centre, NOAA.

Throughout their range belugas inhabit cold Arctic waters, living amongst pack ice, in leads and polynyas in winter and migrating to shallow bays and estuaries of large northern rivers in the summer. Their seasonal movements depend on both oceanographic conditions (primarily the dynamics of ice cover) and the distribution of their primary prey species (Boltunov & Belikov 2002). Typically, belugas travel in pods of 2 to 10 whales, although larger pods are not uncommon (O’Corry-Crowe 2018). Females with young inhabit calm shallower waters along reef edges, islands and large bays. These areas have a warm surface temperature and sand, gravel or mud bottoms that support molluscs, crustacea and bottom fish. On the other hand, adults and weaned young prefer areas where the water depth varies, where surface temperatures are cold, and where there are reef bottoms of sand and gravel or deep bottoms of sandy mud and coarse material.

Belugas swimming in ice-choked waters. Note the lack of dorsal fin. © M. P. Heide-Jørgensen, Greenland Institute of Natural Resources

DIFFICULTIES IN STOCK IDENTIFICATION

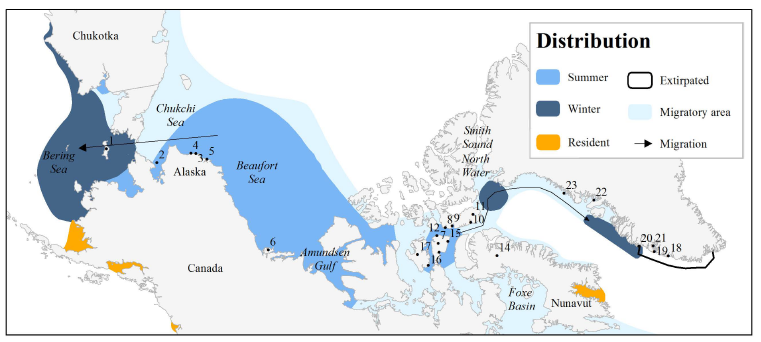

Beluga stocks and distribution as recognised by the Global Review of Monodontids (Hobbs et al. 2019).

Due to the annual migration patterns and the challenges of sampling and studying these animals in the field, researchers have not yet established a well-defined stock identification for belugas. However, determination of stocks for belugas is particularly important since in several areas, beluga numbers have declined considerably over the past century. As beluga hunting continues, it is essential to have knowledge of stock structure, distribution and population size in order to determine sustainable harvest levels.

USING GENETICS AND MIGRATION ROUTES

Genetic studies used to try to differentiate beluga stocks have not shown the same clear results as for some other animals. Difficulties arise in using genetics for belugas because adequate sampling designs are hard to achieve (de March et al. 2002). Due to the difficulty and expense of field work, sample size tends to be lower than desired. Moreover, researchers usually focus their sampling efforts in areas and times during the hunting period rather than throughout their seasonal range.

Additionally, because belugas are social animals and occur in pods of closely related animals, sampled animals may be close relatives rather than random individuals from a stock (Palsbøll et al. 2002). The challenges encountered indicate that genetic studies alone may not suffice to delineate beluga stocks, necessitating a combination of methodologies and information. In the case of belugas, the most effective approach to define a “stock” may be to consider the annual migration route and the hunters who interact with the whales along this pathway (Innes et al., 2002b).

A further complication arises because different genetic analyses yield conflicting results for belugas. For instance, analysis of mitochondrial DNA from belugas harvested in and around Hudson Bay suggests that several separate stocks inhabit the area (Turgeon et al. 2012). In contrast, there is little evidence of separate stocks from analyses of nuclear DNA. As mitochondrial DNA is inherited from the mother only, this suggests that maternally-led “cultural” stocks go to separate summering areas, but mix together during the mating season. This also means that hunters in the same community might harvest from a single stock during the summer, but a mixture of two or more at other times of the year.

Major groups

A genetic study (O’Corry-Crowe et al. 2010) has, however, revealed that beluga stocks can be divided into two major groups:

- Arctic (Svalbard–White Sea–Greenland–Beaufort Sea), and

- Subarctic (Gulf of Alaska) regions

This study suggests a deep divergence between the two major groupings, but periodic gene flow within them, probably during warm periods with lighter ice cover. A further deep division has been found between the St Lawrence River and Eastern Hudson Bay populations and all other Canadian and Greenlandic populations (COSEWIC 2004, de March et al. 2002). The former grouping might have originated from an Atlantic glacial refugium, while the other areas may have been colonised from the west.

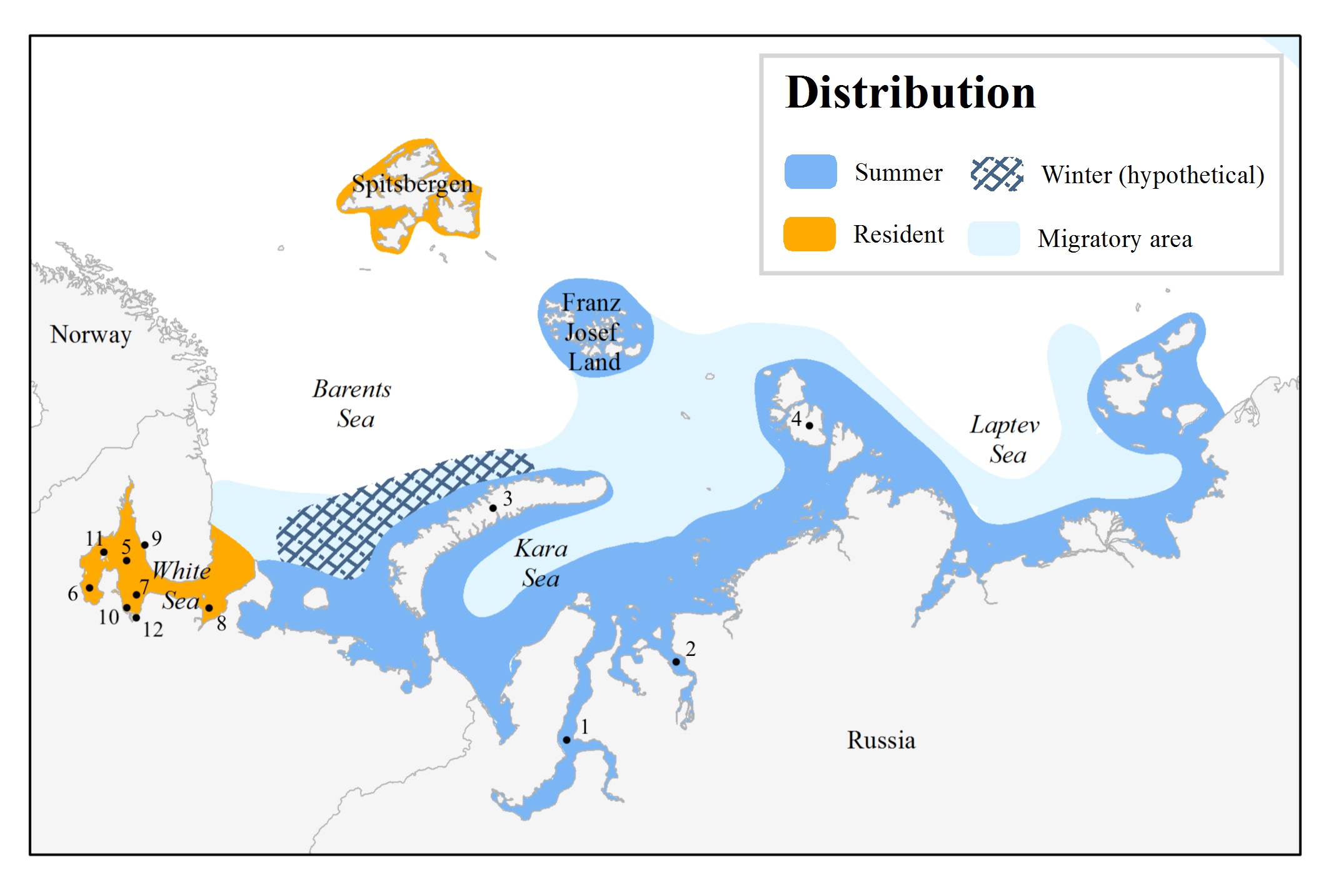

Stocks/Summer Aggregations in the NAMMCO Area

Locations associated with beluga stocks of Svalbard and eastern Russia: (1) Ob Gulf, (2) Yenisey Gulf, (3) Novaya Zemlya, (4) Severnaya Zemlya, (5) White Sea, (6) Onezhsky Bay, (7) Dvinskoy Bay, (8) Mezen’sky Bay, (9) Varzuga River, (10) Severnaya Dvina River, (11) Bolshoy Solovetsky Island, (12) Arkhangelsk. No winter area is shown for the Kara and Laptev seas due to lack of information (Hobbs et al. 2019).

Svalbard

Belugas are resident around Svalbard year-round. During summer they spend most of their time close to glacier fronts (Lydersen et al. 2001). However, when the sea-ice forms, the ice pushes them further offshore, yet they remain close to Svalbard.

Belugas are rare along the east coast of Greenland, likely due to lack of suitable habitat. Whales which do appear there from time to time likely belong to the Svalbard population (Dietz et al. 1994, NAMMCO 2018).

Current data does not suggest a link between the Svalbard stocks and the Barents-Kara-Laptev stock or the White Sea stocks (NAMMCO 2018).

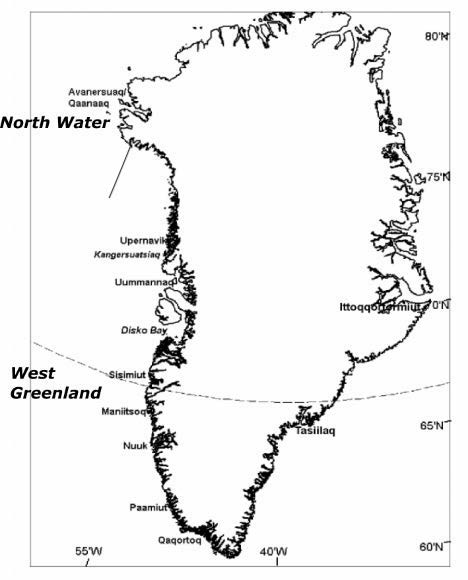

Eastern High Arctic – Baffin Bay and West Greenland

Locations associated with beluga stocks of the Chukchi and Beaufort Seas, Canadian Arctic and West Greenland Numbered locations are: (1) St. Lawrence Island, (2) Kotzebue Sound, (3) Kasegaluk Lagoon, (4) Point Lay, (5) Wainwright, (6) Mackenzie River, (7) Somerset Island, (8) Radstock Bay, (9) Maxwell Bay, (10) Croker Bay, (11) Devon Island, (12) Cunningham Inlet, (13) Creswell Bay, (14) Mary River Mine, (15) Elwin Bay, (16) Coningham Bay, (17) Prince of Wales Island, (18) Qeqertarsuatsiaat, (19) Nuuk, (20) Maniitsoq, (21) Godthåb Fjord, (22) Uummannaq, (23) Upernavik (Hobbs et al. 2019).

The Eastern High Arctic – Baffin Bay (also called “Somerset Island”) stock of belugas is a shared stock between Canada and Greenland. These animals form a “summer aggregation” that spends the summer mainly in the Canadian High Arctic Archipelago, with some animals also in Smith Sound.

In autumn, some beluga from this stock migrate to western Greenland where they stay during the winter, while others winter in the “North Water” polynya in Baffin Bay and Smith Sound (Richard et al. 2001, NAMMCO 2013). You can see the two wintering areas on the stock distribution map.

The segment of beluga stock that migrate along the west coast of Greenland can be found from Qaanaaq in the north to Paamiut in the south in autumn, winter and spring while being rare along this coast in summer (NAMMCO 2000). They migrate past the Upernavik region in October and are found between Disko Bay and Sisimiut in autumn and winter (NAMMCO 2000). Based on satellite tagging data, Heide-Jørgensen et al. (2003) estimated that the proportion of animals moving to West Greenland in the winter was approximately 15% (95% confidence limit 6-35%).

Other Beluga stocks

Ungava

This population of belugas was originally defined by their summering area. It is thought that this population may have been extirpated, or if it still exists, has very low numbers (DFO 2004). Past genetics studies showed high levels of genetic diversity (Smith and Hammill 1986), however belugas from Ungava Bay may now be part of other populations (DFO 2004).

Eastern Hudson Bay

Easter Hudson Bay belugas are genetically different from Western Hudson Bay belugas (Brennin et al. 1997, Brown-Gladden et al. 1997, de March & Postma 2003). They spend the summer mainly in coastal waters extending from Kujjuarapik to Inukjuak, but they can also utilise offshore waters (Smith & Hammill 1986, Kingsley 2000, Gosselin et al. 2002).

Moreover, recent studies indicate that belugas in James Bay may be a separate population from the rest of the Eastern Hudson Bay population (Bailleul et al. 2012). In this study, belugas captured and tagged in James Bay remained very close to where they were captured, while the majority of Eastern Hudson Bay belugas migrated between distinct summer and wintering areas. Bailleul et al. (2012) suggested that decreases in sea ice in recent years may have made James Bay a suitable area for belugas to remain year-round, while ice conditions in the rest of Eastern Hudson Bay still make it necessary for the belugas there to migrate.

Western Hudson Bay

Beluga, Hudson Bay © Ansgar Walk

The beluga of Western Hudson Bay are a large, possibly diverse stock that may contain several sub-stocks, including Northern Hudson Bay, Foxe Basin, and Southern Hudson Bay. The Western Hudson Bay belugas contain many genetic similarities to all other Canadian beluga populations, yet are genetically distinguishable. Therefore, more information is needed to understand the population structure.

Cumberland Sound

The Cumberland Sound stock summers in the inner part of Cumberland Sound and winters beyond the ice edge near the mouth of the Sound (DFO 2002a). They are considered a separate population based on results from satellite tagging, genetics, organochlorine contaminant signatures, and traditional knowledge (Kilabuk 1998).

St Lawrence

The St Lawrence (sometimes called St Lawrence River) stock is a small population thought to have once been part of the Arctic populations (DFO 2004). There does not appear to be any geographic overlap with the other current populations of belugas, and they are also genetically distinct from all the other populations (DFO 2004).

Barents-Kara-Laptev Seas

Little information is available on this stock. Based on opportunistic sightings data from oil/gas exploration, tourist cruises, and scientific expeditions, belugas from this stock are thought to concentrate in summer mostly in the estuaries of large rivers (Ob, Yenisey) and in the waters of the archipelagos (Franz Josef Land, south of Novaya Zemlya, Severnaya Zemlya) (NAMMCO 2018). Nonetheless, at the present time no data is available on seasonal migratory routes. Analysis of mitochondrial DNA from 16 harvested or beached belugas from the Kara and western Laptev Seas revealed the same haplotypes as found in Svalbard belugas (NAMMCO 2018). However, the number of genetic samples was too small to make any conclusions on stock structure. It is likely that there are several different beluga stocks which use the major bays, estuaries, and archipelago waters (e.g. Franz Josef Land).

White Sea

Data on distribution and movements suggests that belugas in the White Sea form a resident population that may consist of several stocks (NAMMCO 2018). Field observations indicate that White Sea belugas occur in discrete summer nursery aggregations associated with major bays: Onezhsky, Dvinskoy and Mezen’sky. However, more data are necessary to understand population structure in greater detail.

© M. P. Heide-Jørgensen, Greenland Institute of Natural Resources

Current Abundance and Trends

The remote range, wide distribution range and mobility of beluga whales makes it rather difficult to estimate their abundance. Thus, the most common method of counting them is aerial surveys. However, the researchers must correct the results obtained from these surveys for whales that are at the surface but missed by observers, and those that are below the surface and out of sight when the survey airplane is overhead. Another challenge lies in comparisons between surveys, which are not always possible since surveys rarely follow exactly the same protocol of timing and area covered.

SVALBARD

In 2018, Vacquié-Garcia et al. (2020) carried out the first-ever survey for this area and estimated an abundance of 549 animals (95% CI: 436-723) when corrected for availability bias.

Eastern High Arctic – Baffin Bay and West Greenland

The most recent estimate for the Eastern High Arctic – Baffin Bay summer aggregation comes from an aerial survey in 1996, which estimated 21,213 belugas (95% CI: 10,985 to 32,619) (Innes et al. 2002a). This estimate takes into account both whales missed by observers and those that might be submerged. In the meantime, researchers have recognized the need to update this estimate (NAMMCO 2018). Previous estimates from the early 1970’s gave a very rough estimate of 10,000 belugas (Koski et al. 2002), and surveys conducted in the late 1970’s estimated that 10,250 to 12,000 belugas were involved in the fall migration out of the central Arctic (Koski et al. 2002).

Beluga whales at bellsund, Svalbard © T, Jacobsen

Aerial surveys conducted in West Greenland between 1981 and 1994 found that numbers of beluga whales decreased by 62% during that period, probably due to over-harvesting (Heide-Jørgensen & Reeves 1996). Further surveys in 1998 and 1999 confirmed the decline and estimated 7,941 (95% CI: 3650–17,278) belugas in West Greenland, including whales missed by the observers and whales that were submerged during the survey (Heide-Jørgensen & Acquarone 2002). New management measures (see section on management) may, however, have reversed this decline. A survey carried out in 2006 revealed an abundance estimate of 10,595 (95% CI: 4,904–24,650) (NAMMCO 2010). The most recent (2012) estimate for belugas that winter in West Greenland was 9,072 whales (95% CI: 4,895 to 16,815 (Heide-Jørgensen et al. 2016).

Recent surveys

Any apparent trends of increase or decline in this population are difficult to assess since the uncertainty for all estimates are relatively large. While this stock is likely depleted from its historical size, there is some evidence of recovery. More recent surveys in West Greenland have shown an increasing number of belugas in the stock segment that migrates to West Greenland (see Stock Status). Despite the indicated population increase and projected continuation of this trajectory since the introduction of catch quotas in Greenland(Heide-Jørgensen et al. 2017), the stock as a whole is still considered depleted (NAMMCO 2018).

Stock Status

Svalbard

After the first abundance estimate in 2018, which resulted in an estimate of 549 (CI 436-723) individuals, belugas in Svalbard are now classified as endangered (EN) on the Norwegian Red List. Out of all the stocks in NAMMCO’s management area, this one is the smallest and least-known. Climate change is expected to negatively impact this population in the future (Kovacs et al 2011).

Eastern High Arctic – Baffin Bay

It is not entirely clear whether the abundance of this stock is stable or increasing. Winter surveys off West Greenland indicate an increase since the imposition of catch limits (see section on abundance). Continued population growth is also projected (Heide-Jørgensen et al. 2017). This is a large stock (possibly 20,000 animals) and removals are considered sustainable, so the level of concern for this stock has been deemed to be low (NAMMCO 2018).

West Greenland Component

In 2020, following a precautionary approach and a request from Greenland, the NAMMCO-JCNB Joint Working Group (JWG) performed an assessment for beluga north of Cape York (in the area around Qaanaaq) as a separate stock – the North Water. The placement of a border at Cape York to separate the West Greenland and North Water stocks was deemed most reasonable based on the available evidence from satellite tracking, timing of catches, and genetic data. As a result, the West Greenland stock contains belugas south and east of Cape York and north of 65°, while the proposed North Water stock includes the belugas in the North Water polynya west and north of Cape York into Smith Sound.

Following the assessment performed in 2020, for the newly defined West Greenland stock, the JWG recommended that to maintain a 70% probability for population increase, there should be an annual landed catch of no more than 265 individuals (NAMMCO-JCNB JWG, 2020). For the newly proposed North Water stock, to maintain a 70% probability for population increase, an annual landed catch of no more than 37 individuals was recommended.

Reviewing the status of all belugas and narwhals

© M.P. Heide-Jørgensen

In March 2017, NAMMCO organised a Global Review of Monodontids (GROM), which discussed the conservation status, threats, and data gaps for all stocks of belugas and narwhals globally. The last review prior to this was done almost 20 years ago, and a large amount of new information has become available since then – especially on stock identity, movements, abundance, and threats to the populations. Additionally, there are many new stressors that have emerged in the last 20 years, especially related to climate change.

Stock experts representing Greenland, Canada, Alaska, Russia, the Government of Nunavut, Nunavut Tunngavik, Inc., the Inuvialuit Settlement Area and the Nunavik Wildlife Management Board participated.

The report (NAMMCO 2018) can be found here and the Global Review of the Conservation Status of Monodontid Stocks was published in 2019.

DECLINE, SOUND MANAGEMENT, AND RECOVERY

© Kristin Laidre

Concern over a decline in belugas from the Eastern High Arctic-Baffin Bay stock that winter in West Greenland led to the introduction of regulations during the 1990s with the intention of reducing and controlling catches. Consequently, the drive hunt in West Greenland, which was the main method of beluga capture at the time, was prohibited in 1995 (Heide-Jørgensen & Rosing-Asvid 2002).

In the year 2000, the Scientific Committee of NAMMCO advised that the animals visiting West Greenland in the winter were substantially depleted and that any delay in reducing the catch to about 100 animals per year would result in further population decline and delay the recovery of this stock (NAMMCO 2001). Thus, a quota of 340 beluga per year was established for West Greenland in 2004. Catches and quotas have fluctuated since then, with catches ranging from 120 to 290 for West Greenland.

There is evidence that the introduction of catch quotas and management measures may already be having a positive effect on the population (Heide-Jørgensen et al. 2016).

Assessments have indicated that a harvest of up to 310 animals per year will allow the population to continue to recover, and that current harvest levels are therefore sustainable (NAMMCO 2010, 2012a).

Management

Belugas inhabit the waters of two NAMMCO member states: Norway and Greenland.

Norway does not presently permit the harvest of belugas in its territory and Greenland regulates the harvest with advice from a bilateral management body in cooperation with NAMMCO.

Shared Management

The stock of belugas that winters off West Greenland summers in Arctic Canada. Therefore, management is a shared responsibility between Greenland and Canada. Greenland and Canada have therefore established a bilateral management body, the Canada/Greenland Joint Commission on the Conservation and Management of Narwhal and Beluga (JCNB). Furthermore, the JCNB has a joint Scientific Working Group (JWG) with the NAMMCO Scientific Committee Working Group on the Population Status of Narwhal and Beluga in the North Atlantic. This NAMMCO-JCNB JWG provides advice at the request of the JCNB and NAMMCO, pertaining to such issues as stock delineation, total allowable catches and threats to beluga and narwhal populations. The JCNB Commission meets periodically to receive this advice and provide management advice to Canada and Greenland.

Greenland

The Ministry of Fisheries, Hunting and Agriculture is responsible for regulating beluga whaling in Greenland. Municipal authorities enforce regulations on the hunting seasons for belugas and specify the permitted weapons and equipment for hunting. Hunters must then report successful whale hunts to municipal authorities to facilitate the monitoring of the harvest. Furthermore, wildlife officers monitor compliance with quotas and other regulations at the local level.

Sound management gives results

Greenland has set quotas for belugas in response to JCNB and NAMMCO advice. In 2004, a quota of 320 beluga per year was established for West Greenland. Catches and quotas have fluctuated since then, with catches ranging from 120 to 290 for West Greenland.

There is evidence that these new management measures may have already had a positive effect on the population (Heide-Jørgensen et al 2016). Recent assessments indicate that a harvest of up to 310 animals per year will allow the population to continue to recover, and that current harvest levels are therefore sustainable (NAMMCO 2010, 2012a).

Recent Management Advice

Until 2020, no assessment of belugas in the area around Qaanaaq (Greenland) was performed, only an informal advice given that catches at existing levels were sustainable. In 2020, following a request from Greenland, the NAMMCO-JCNB Joint Working Group (JWG) adopted a precautionary approach separating the West Greenland component of the Eastern High Arctic Baffin Bay stock at Cape York into a re-defined West Greenland stock and a proposed new “North Water” stock. The JWG then performed an assessment for belugas in both of these areas.

Following the 2020 assessment, the JWG recommended that to maintain a 70% probability for population increase in the proposed North Water stock, there should be an annual landed catch of no more than 37 individuals north and west of Cape York (NAMMCO-JCNB JWG, 2020). For West Greenland (south and east of Cape York and north of 65°) the JWG recommended that to maintain a 70% probability for population increase, there should be an annual landed catch of no more than 265 individuals (NAMMCO-JCNB JWG, 2020).

Seasonal closures

Following the recommendations of the JWG, in 2021, the NAMMCO SC reiterated previous recommendations that there be no hunt south of 65˚ in Greenland and that the following seasonal closures be implemented: a) Northern (Uummannaq, Upernavik, Savissivik): June through August; b) Central (Disko Bay): June through October; c) Southern (South of Kangaatsiaq): May through October. The NAMMCO SC has recommended these seasonal and geographical closures for several years as a way to try and protect the few animals that may be present in these areas in the summer and thereby help to repopulate depleted stocks (NAMMCO 2021a).

The NAMMCO Management Committee has not adopted these recommendations for seasonal and geographical closures, unconvinced that they would achieve the desired aim due to environmental changes and the presence of other human activities, and therefore a small annual quota (5 animals in 2021) for beluga south of 65˚ in Greenland remains (NAMMCO 2021a&b).

STATUS ACCORDING TO OTHER ORGANIZATIONS

Belugas are currently listed in Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) (as are all species of cetaceans not listed on Appendix I). CITES is a legally-binding multilateral environmental agreement that aims to ensure that international trade does not threaten the survival of species in the wild. Both Denmark (Greenland) and Norway are signatories to the convention. A listing in Appendix II means that an export permit shall only be granted when the Scientific Authority of the State of export has advised that such export will not be detrimental to the survival of the species in the wild.

The global IUCN “Red list” lists belugas as “Least Concern” in an assessment made in 2017.

UTILISATION

Belugas have long been a staple food resource for indigenous peoples throughout the Arctic, and they continue to be an important part of northern diets today. Historically, the beluga whale served various purposes (Kilabuk 1998, Sejersen 2001). The skin and attached subcutaneous fat was and is considered a delicacy called muktuk (various spellings and pronunciations, including maktaaq and mattak). The meat varied in quality depending on the cut and was eaten raw, dried or cooked, or used as dog food. Sometimes the meat and muktuk was aged and prepared in specific ways to make traditional delicacies.

The flippers, organs and intestines were also used as food. The skin from the top part of the whale was cut and prepared to make rope, and the tendons were used to make sinew for sewing. The blubber was rendered to oil and used in traditional lamps (qulliq) as a source of light and heat. Additionally, the bones had multiple uses, including as a food source, construction material, and for carving. While modern materials have replaced many of these traditional uses, beluga muktuk and meat are still an important and welcome part of the diet in some areas of Arctic Canada and Greenland.

HUNTING

The following descriptions of hunting methods in Canada and Greenland have been taken from the NAMMCO Expert Group Meeting to Assess the Hunting Methods for Small Cetaceans, held in 2011 (NAMMCO 2012b):

Harpoons

Belugas in West Greenland and Canada are hunted during the spring, summer and fall from small boats, at the ice edge or at ice cracks. The kayak is still in use for hunting in some areas of West Greenland. In this type of hunting, one or two kayaks approach the animal quietly, and the hunter uses a hand-held harpoon with a detachable head (Greenlandic: tuukaak). The harpoon head is attached by a line to a float (Greenlandic: quataq) and then to drag or brake (Greenlandic: miutak) which slows the wounded animal. The hunter then shoots the whale with a high-powered rifle when it resurfaces.

Similar hunting methods are used from small motor boats and from the ice in Greenland and Canada. Ideally, the whale is harpooned first to secure it; it is thereafter dispatched using a rifle. The harpoon strike alone is sufficient to kill the animal in some cases. In other cases, the beluga is shot first to wound it and slow it down so it can be secured using a harpoon and line.

Nets

n the far north of Greenland and certain regions of Canada, hunters employ nets to capture belugas . This technique is used particularly during the dark seasons and in very heavy ice conditions. The belugas swim into the net, become entangled and will drown since they cannot surface. In cases where they remain alive, hunters will shoot them during net inspections.

Distribution of catch

Historically, the catch of belugas or other large animals was divided and shared amongst participating hunters and their extended families according to complex traditional rules (Inuktitut ningiqtuq, Greenlandic ningerpoq), which helped to ensure that the entire camp or community received a portion of the catch (Wenzel 1995, Sejersen 2001). More recently, the regulation of beluga hunting and changing of hunting methods and equipment have led to changes in the sharing system (Sejersen 2001). In Greenland particularly, hunters sell part of the catch in the open-air markets (Greenlandic Kalaalimineerniarfik, Danish brædtet) present in every village and town. This provides a welcome source of income for hunters. Commercial sale of beluga products is not widespread in Nunavut, although this is starting to change.

Hunting Past and Present

Svalbard

Russians harvested belugas at Svalbard beginning in the 18th century. Little information is available on catch numbers from this time, although the best known year is 1818, when a crew overwintering caught about 1,200 belugas (Gjertz & Wiig 1994). Norwegians also began hunting belugas around Svalbard in 1866 and continued up until the early 1960s. Over that period, more than 15,000 animals were taken (Gjertz & Wiig 1994).

Eastern High Arctic – Baffin Bay and West Greenland

Commercial harvesting of beluga in West Greenland and Baffin Bay began in the late 1800s. The occurrence of belugas in West Greenland has changed over the past 90 years, largely due to changes in hunting patterns. The introduction of motor boats to the area in the early 20th century led to increased catches. After a period with large catches in Nuuk (from 1906–22) and in Maniitsoq (1915–29), beluga disappeared from the area south of 66° N (Heide-Jørgensen & Acquarone 2002). Between 1927 and 1951, large catches were reported in the southern part of the municipality of Upernavik, and since 1970 in the northern part. Catches in this area in the 1990s were about 700 whales per year (Heide-Jørgensen & Rosing-Asvid 2002). Since 2010, the catches in West Greenland have typically been between 100-300 animals per year.

Catches in NAMMCO member countries since 1992

| Country | Species (common name) | Species (scientific name) | Year or Season | Area or Stock | Catch Total | Quota (if applicable) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2023 | Total | 151 | 575 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2023 | Qaanaaq | 10 | 31 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2023 | West | 136 | 530 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2023 | East | 5 | 14 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2022 | Total | 233 | 595 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2022 | West | 151 | 509 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2022 | East | 28 | 30 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2022 | Qaanaaq | 54 | 56 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2021 | North Water + West Greenland | 306 | 608 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2020 | North Water + West Greenland | 189 | 593 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2019 | Qaanaaq | 20 | |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2019 | West | 263 | 452 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2019 | Total | 263 | 472 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2018 | Qaanaaq | 5 | 22 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2018 | West | 208 | 320 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2018 | Total | 213 | 342 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2017 | Qaanaaq | 32 | 20 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2017 | West | 164 | 320 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2017 | Total | 196 | 340 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2016 | Qaanaaq | 16 | 20 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2016 | West | 187 | 320 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2016 | Total | 203 | 340 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2015 | Qaanaaq | 7 | 20 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2015 | West | 120 | 353 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2015 | Total | 127 | 373 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2014 | Qaanaaq | 31 | 20 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2014 | West | 240 | 385 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2014 | Total | 271 | 405 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2013 | Qaanaaq | 26 | 20 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2013 | West | 279 | 330 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2013 | Total | 305 | 350 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2012 | Qaanaaq | 24 | 20 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2012 | West | 187 | 450 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2012 | Total | 211 | 470 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2011 | Qaanaaq | 7 | 20 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2011 | West | 144 | 290 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2011 | Total | 151 | 310 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2010 | Qaanaaq | 1 | 20 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2010 | West | 148 | 290 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2010 | Total | 149 | 310 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2009/2010 | Qaanaaq | 16 | 20 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2009/2010 | West | 225 | 290 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2009/2010 | Total | 241 | 310 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2008/2009 | Qaanaaq | 50 | 20 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2008/2009 | West | 250 | 235 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2008/2009 | Total | 300 | 255 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2007/2008 | Qaanaaq | 6 | 20 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2007/2008 | West | 115 | 145 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2007/2008 | Total | 121 | 165 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2006/2007 | Qaanaaq | 14 | 20 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2006/2007 | West | 139 | 140 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2006/2007 | Total | 153 | 160 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2005/2006 | Qaanaaq | 2 | 20 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2005/2006 | West | 121 | 300 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2005/2006 | Total | 123 | 320 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2004/2005 | Qaanaaq | 2 | 20 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2004/2005 | West | 47 | 300 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2004/2005 | Total | 49 | 320 |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2003 | Qaanaaq | 54 | No quota |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2003 | West | 418 | No quota |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2003 | Total | 472 | No quota |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2002 | Qaanaaq | 0 | No quota |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2002 | West | 399 | No quota |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2002 | Total | 399 | No quota |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2001 | Qaanaaq | 1 | No quota |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2001 | West | 397 | No quota |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2001 | Total | 398 | No quota |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2000 | Qaanaaq | 4 | No quota |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2000 | West | 606 | No quota |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 2000 | Total | 610 | No quota |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 1999 | Total | 493 | No quota |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 1998 | Total | 746 | No quota |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 1997 | Total | 577 | No quota |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 1996 | Total | 521 | No quota |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 1995 | Total | 606 | No quota |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 1994 | Total | 488 | No quota |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 1993 | Total | 475 | No quota |

| Greenland | Beluga | Delphinapterus leucas | 1992 | Total | *No reported catches | No quota |

This database of reported catches is searchable, meaning you can filter the information by for instance country, species or area. It is also possible to sort it by the different columns, in ascending or descending order, by clicking the column you want to sort by and the associated arrows for the order. By default, 30 entries are shown, but this can be changed in the drop-down menu, where you can decide to show up to 100 entries per page.

Carry-over from previous years are included in the quota numbers, where applicable.

You can find the full catch database with all species here.

For any questions regarding the catch database, please contact the Secretariat at nammco-sec@nammco.no.

SHIPPING NOISE

With few exceptions, belugas inhabit isolated areas subject to seasonal ice cover that are not frequently used as shipping lanes. However, the southernmost beluga stock inhabits the St Lawrence River in Canada, which is one of the busiest shipping routes in the world. Here they are subject to high levels of noise, both from ships and whale-watching operations (McQuinn et al. 2011). The population-level consequences of shipping noise to this threatened population are unknown. However, belugas do appear to become habituated to some levels of noise over time.

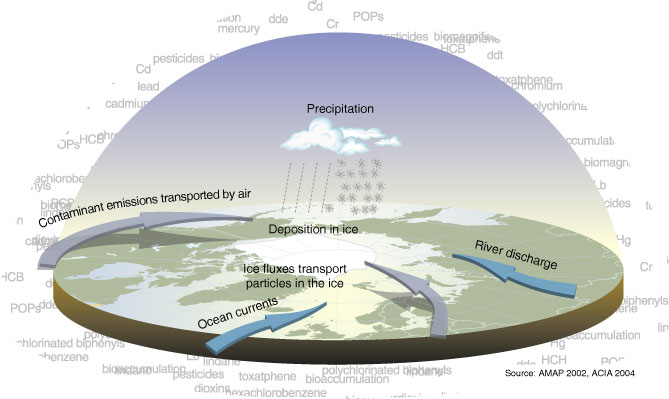

CONTAMINANTS

More so than for other Arctic marine mammal species, the beluga is susceptible to contaminant exposure because of its habit of occupying river estuaries during parts of the summer. Rivers carry pollutants from inland and therefore tend to be more contaminated than offshore marine areas. One population particularly susceptible to marine contaminants is the St Lawrence River stock, because its habitat is the densely populated and heavily polluted St Lawrence River basin (DFO 2012). However, some other stocks, particularly those inhabiting northeastern Russia, may also be exposed to high levels of contaminants.

Belugas are top predators in the marine food web and therefore tend to accumulate relatively high levels of some contaminants in their tissues. Particularly high levels of organic contaminants (e.g. pesticides) are found in the fatty blubber layers, to the extent that beach-cast belugas in the St Lawrence river basin area must sometimes be treated as toxic waste.

Contaminants can affect survival in several ways, including increasing the rates of chronic diseases such as cancers, disrupting the immune system and increasing vulnerability to pathogens and parasites. They can also disrupt the reproductive system and decrease reproductive success (DFO 2012). While the extent to which contaminants are actually affecting the survival and reproduction at the population level are not known, contaminants are considered to be a major threat to the St Lawrence population (DFO 2012). Some researchers have observed a relatively high incidence of cancerous tumors in beach-cast carcasses of beluga whales, leading some to link this to environmental contamination (Martineau et al. 2002). This conclusion is, however, controversial, predominantly because the incidence of cancer in the general population is difficult to infer from the incidence in carcasses (Hammill et al. 2003).

EFFECTS OF CLIMATE CHANGE

In recent years, the eastern part of Baffin Bay and Davis Strait has had lighter pack ice cover during the winter and spring. Belugas have responded to this by extending their winter distribution farther west and north. This also affects the success of hunters in West Greenland as they must range further from the coast to gain access to belugas in light ice years. These effects demonstrate the influence of climate change on this stock of belugas and offers hope that this species might be flexible enough to adapt to a rapidly changing climate.

ENTRAPMENTS

Like narwhals and bowheads, belugas are susceptible to occasional entrapments in sea ice, which can, if prolonged, lead to their death by starvation, suffocation, predation or human harvesting (Heide-Jørgensen et al. 2002). While this is a form of natural mortality that belugas as a species have survived throughout their history, it is possible that human activities (and particularly seismic exploration within beluga habitat) might disrupt migration timing or routes in such a way as to increase the frequency of entrapment. Possible incidences of this have been observed for narwhal (Heide-Jørgensen et al. 2013) and similar occurrences are possible for belugas. In addition, climate change might also disrupt migration patterns in such a way as to change the frequency of entrapments.

COMMERCIAL FISHING

Most beluga stocks inhabit areas with little or no commercial fishing. Again, the St Lawrence River stock is exceptional in this regard as it lives year-round in an area with heavy commercial fishing (DFO 2012). Researchers have documented declines in several fish stocks, including those that are crucial in the beluga diet, within this area. However, it remains unclear whether these declines are exerting a population-level impact on the beluga stock.

Commercial fisheries, primarily for Greenland halibut (Reinhardtius hippoglosoides), have expanded into Baffin Bay and Davis Strait, which provides the overwintering habitat for some stocks of belugas (DFO 2007, Laidre et al. 2004). While Greenland halibut are a primary prey species for narwhal, they are less important for belugas, which tend to consume more pelagic prey species.

Research in NAMMCO Member Countries

Greenland

Research carried out by Greenland has included the collection and analysis of samples for genetic studies, the application of satellite tags, and abundance surveys. The latter have provided important information on the size of the population wintering off West Greenland and the trends in abundance over time. Ten surveys have been carried out off West Greenland since 1981, most recently in 2008 (Heide-Jørgensen & Acquarone 2002, Heide-Jørgensen et al. 2010, NAMMCO 2010). These surveys have covered an area from Disko Island in the north, south to Paamiut, and from the coastline out to 80 km offshore. Moreover, they have been conducted using aircraft, with experienced observers who record data using distance sampling techniques. The more recent surveys have also used video and still photography to record ice and environmental conditions, and to collect images of whales. New marine mammal surveys are scheduled for 2021 (National Progress Report Greenland 2020).

Tagging a beluga in Svalbard, Norway. © K. Kovacs-C. Lydersen / Norwegian Polar Institute

It is rare to have over 30 years of survey data on distribution and abundance of any species and this provides a rich source of data for assessing the possible impacts of a changing climate on an Arctic species. Consequently, Heide-Jørgensen et al. (2010) used these surveys to demonstrate that the recent trend towards lighter winter ice cover off West Greenland has led to a shift in beluga distribution to more offshore areas. Belugas apparently take advantage of the reduced ice cover offshore to access areas that were inaccessible to them in previous years. This offers hope that this species might be flexible enough to adapt to a rapidly changing climate.

Tagging of beluga in Svalbard, Norway. © K. Kovacs-C. Lydersen / Norwegian Polar Institute

Tagging

Greenland has also played a significant role in understanding the seasonal movements of belugas through the use of satellite-linked transmitters/receivers. Researchers attach these compact devices, often referred to as “satellite tags”, on to captured whales before releasing them. The tags collect data on diving behaviour and movements, and transmit them via satellite during the brief period when the tag breaches the sea surface.

The capture process involves isolating individual belugas or small groups and slowly driving them towards the shore using small boats. The whales are then immobilised on the beach using nets and ropes and the tag is surgically attached to the dorsal ridge. On average, the tags transmit data for 2-3 months before falling off the whale, thus ending communication (Richard et al. 2001).

The tag is attached using plastic bolts through the dorsal ridge. It transmits data to a satellite when the whale surfaces. The tags fall off usually in less than 6 months. © K. Kovacs-C. Lydersen / Norwegian Polar Institute

While it has proven difficult to tag belugas during their winter occupation off West Greenland waters, Greenland researchers have also been involved in tagging operations in Arctic Canada. These applications have demonstrated conclusively that some belugas that summer in Arctic Canada do migrate to West Greenland for the winter (Richard et al. 2001). The tags have also provided important data on diving that has been used to derive correction factors for aerial surveys.

Genetic studies

Greenland researchers have actively participated in genetic studies of beluga populations. These studies use small samples collected from beluga hunts, tagging operations and in some cases, biopsies. While the social structure of beluga populations has made the interpretation of genetic data challenging (de March et al.2002, Palsbøll et al. 2002), genetic studies have been successful in discriminating the major divisions in beluga populations.

Norway

Similar to Greenland, Norwegian researchers have also used tagging techniques to monitor the movement and diving behaviour of belugas around Svalbard. Here, belugas do not seem to make long-distance migrations, remaining within the archipelago throughout most of the year (Lydersen et al. 2001). An innovative application of tagging was to use belugas as oceanographic “adaptive samplers” to monitor temperature and salinity in areas that are normally inaccessible to research vessels because of ice conditions (Lydersen et al. 2002). The Norwegian Polar Institute conducted the first-ever aerial survey for estimating the number of belugas in the Svalbard area in July and August 2018. Additionally, seven acoustic recorders listening mainly for bowhead whales, belugas and narwhals were deployed the same autumn and have been serviced and redeployed in 2020 for ongoing data collection (National Progress Report Norway 2018, 2020).

Alvarez-Flores, C.M. and Heide-Jørgensen, M.P. (2004). A risk assessment of the sustainability of the harvest of beluga Delphinapterus leucas (Pallas 1776) in West Greenland. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 61(2), 274–286. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.icesjms.2003.12.004

Bailleul, F., Lesage, V., Power, M., Doidge, D.W. and Hammill, M.O.( 2012). Differences in diving and movement patterns in two groups of beluga whales in a changing Arctic environment reveal discrete populations. Endangered Species Research, 17(1), 27–41. http://dx.doi.org/10.3354/esr00420

Boltunov, A. N. and Belikov, S.E. (2002). Belugas (Delphinapterus leucas) of the Barents, Kara and Laptev seas. NAMMCO Scientific Publications, 4, 149–168. http://dx.doi.org/10.7557/3.2842

COSEWIC. (2004). COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the beluga whale Delphinapterus leucas in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. ix + 70 pp. https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/species-risk-public-registry/cosewic-assessments-status-reports/beluga-whale.html

Dahl, T., Lydersen, C., Kovacs, K.M., Falk-Petersen, S., Sargent, J., Gjertz, I. and Gulliksen, B. (2000). Fatty acid composition of the blubber in white whales (Delphinapterus leucas). Polar Biology, 23, 401–409. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s003000050461

de March, B.G.E. and Postma, L.D. (2003). Molecular genetic stock discrimination of belugas (Delphinapterus leucas) hunted in Eastern Hudson Bay, Northern Quebec, Hudson Strait, and Sanikiluaq (Belcher Islands), Canada, and comparisons to adjacent populations. Arctic, 56(2), 111–124. https://doi.org/10.14430/arctic607

de March, B.G.E., Maiers, L.D. and Friesen, M.K. (2002). An overview of genetic relationships of Canadian and adjacent populations of belugas (Delphinapterus leucas) with emphasis on Baffin Bay and Canadian eastern Arctic populations. NAMMCO Scientific Publications, 4, 17–38. http://dx.doi.org/10.7557/3.2835

Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO). (2002b). Underwater World – The Beluga. DFO, Communications Directorate. Ottawa, ON. Available at https://waves-vagues.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/Library/40724773.pdf

Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO). (2002a). Cumberland Sound Beluga. Stock Status Report E5-32. DFO, Central and Arctic Region, Winnipeg, MB. Available at https://waves-vagues.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/Library/274059.pdf

Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada(DFO). (2002c). Northern Quebec (Nunavik) Beluga (Delphinapterus leucas). Stock Status Report E4-01. Available at https://waves-vagues.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/Library/345643.pdf

Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO). (2007). Development of a Closed Area in NAFO 0A to protect Narwhal Over-Wintering Grounds, including Deep-sea Corals. DFO Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat, Sci. Resp. 2007/002. Available at https://waves-vagues.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/Library/329004.pdf

Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO). (2012). Recovery Strategy for the beluga whale (Delphinapterus leucas) St. Lawrence Estuary population in Canada. Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series, 88 pp + X pp. Available at https://www.sararegistry.gc.ca/virtual_sara/files/plans/rs_st_laur_beluga_0312_e.pdf

Dietz, R., Heide-Jørgensen, M. P., Born, E. W. and Glahder, C. M. (1994). Occurrence of narwhals (Monodon monoceros) and white whales (Delphinapterus leucas) in East Greenland. Meddelelser om Grønland Bioscience, 39, 69–86. https://bit.ly/2y2Taoy

Doniol-Valcroze, T, Hammill, M. O. and Lesage, V. (2011). Information on abundance and harvest of eastern Hudson Bay beluga (Delphinapterus leucas). DFO Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat, Res. Doc. 2010/121. iv + 13 p. Available at http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/csas-sccs/Publications/ResDocs-DocRech/2010/2010_121-eng.html

Doniol-Valcroze, T. and Hammill, M.O. (2011). Information on abundance and harvest of Ungava Bay beluga. DFO Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat, Res. Doc. 2011/126. Available at http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/csas-sccs/Publications/ResDocs-DocRech/2011/2011_126-eng.html

Ferguson, S.H., Higdon J. and Chmelnitsky E.G. (2010). The Rise of Killer Whales as a Major Arctic Predator. In S.H. Ferguson et al. (eds.), A Little Less Arctic. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-9121-5_6

Gjertz, I. and Wiig, Ø. (1994). Distribution and catch of white whales (Delphinapterus leucas) at Svalbard. Meddelelser om Grønland – Bioscience, 39, 93–97.

Gosselin J.-F., Lesage V. and Hammill M.O. (2009). Abundance indices of belugas in James Bay, eastern Hudson Bay and Ungava Bay in 2008. DFO Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat, Res. Doc. 2009/006. iv + 25 p. Available at http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/csas-sccs/publications/resdocs-docrech/2009/2009_006-eng.htm

Hammill M.O., Lesage V., Gosselin J.-F., Bourdages H., de March B.G.E. and Kingsley M.C.S. (2004). Evidence for a decline in northern Quebec (Nunavik) belugas. Arctic, 57(2), 183–195. https://doi.org/10.14430/arctic494

Hammill, M.O., Kingsley, M.C.S. and Lesage, V. (2012). Cancer in Beluga from the St. Lawrence Estuary. (Correspondence). Environmental Health Perspectives 111.2 (2003), A77+. Academic OneFile. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.111-a77c

Hammill, M.O., Measures, L.N., Gosselin, J.-F. And Lesage, V. (2007). Lack of recovery in St. Lawrence Estuary beluga. DFO Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat, Res. Doc. 2007/26. Available at http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/csas-sccs/publications/resdocs-docrech/2007/2007_026-eng.htm

Hammill M.O., Mosnier A., Gosslein J.-F., Matthews C.J.D., Marcoux M., and Ferguson S.H. (2017). Management approaches, abundance indices and total allowable harvest levels of belugas in Hudson Bay. DFO Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat.Res. Doc. 2017/062. iv + 43 p.

Heide-Jørgensen, M.P. and Teilmann, J. (1994). Growth, reproduction, age structure and feeding habits of white whales (Delphinapterus leucas) in West Greenland waters. Meddelelser om Grønland Bioscience, 39, 195–212. https://bit.ly/3bKhUAv

Heide-Jørgensen, M.P. and Reeves, R.R. (1996). Evidence of a decline in beluga, Delphinapterus leucas, abundance off West Greenland. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 53(1), 61–72. https://doi.org/10.1006/jmsc.1996.0006

Heide-Jørgensen, M.P. and Rosing-Asvid, A. (2002). Catch statistics for belugas in West Greenland 1862 to 1999. NAMMCO Scientific Publications, 4, 127–142. http://dx.doi.org/10.7557/3.2840

Heide-Jørgensen, M.P. and Acquarone, M. (2002). Size and trends of the bowhead whale, beluga and narwhal stocks wintering off West Greenland. NAMMCO Scientific Publications, 4, 191–210. http://dx.doi.org/10.7557/3.2844

Heide-Jørgensen, M.P., Richard, P., Ramsay, M. and Akeeagok, S. (2002). Three recent ice entrapments of Arctic cetaceans in West Greenland and the eastern Canadian High Arctic. NAMMCO Scientific Publications, 4, 143–148. http://dx.doi.org/10.7557/3.2841

Heide-Jørgensen, M.P., Richard, P., Dietz, R., Laidre, K.L., Orr, J. and Schmidt, H.C. (2003). An estimate of the fraction of belugas (Delphinapterus leucas) in the Canadian High Arctic that winter in West Greenland. Polar Biology, 26, 318–326. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00300-003-0488-x

Heide-Jørgensen, M.P., Laidre, K.L., Borchers, D., Marques, T.A., Stern, H. and Simon, M. (2010). The effect of sea-ice loss on beluga whales (Delphinapterus leucas) in West Greenland. Polar Research, 29(2), 198–208. https://doi.org/10.3402/polar.v29i2.6061

Heide-Jørgensen, M.P., Guldborg Hansen, R., Westdal, K., Reeves, R.R. and Mosbech, A. (2013). Narwhals and seismic exploration: Is seismic noise increasing the risk of ice entrapments? Biological Conservation, 158, 50–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2012.08.005

Heide-Jørgensen M.P., Sinding M.H., Nielsen N.H., Rosing-Asvid A. and Hansen R.G. (2016) Large numbers of marine mammals winter in the North Water polynya. Polar Biology, 39(9), 1605–1614. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00300-015-1885-7

Heide-Jørgensen MP, Hansen RG, Fossette S, Nielsen NH, Borchers DL, Stern H and Witting L. (2017). Rebuilding beluga stocks in West Greenland. Animal Conservation, 20(3), 282–293. https://doi.org/10.1111/acv.12315

Higdon, J.W. and Ferguson, S.H. (2009). Loss of Arctic sea ice causing punctuated change in sightings of killer whales (Orcinus orca) over the past century. Ecological Applications, 19(5), 1365–1375. https://doi.org/10.1890/07-1941.1

Hobbs, K.E., Muir, D.C.G., Michaud, R., Beland, P., Letcher, R.J. and Norstrom, R.J. (2003). PCBs and organochlorine pesticides in blubber biopsies from free-ranging St. Lawrence River Estuary beluga whales (Delphinapterus leucas), 1994–1998. Environmental Pollution, 122(4), 291–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0269-7491(02)00288-9

Hobbs, R. C., Reeves, R. R., Prewitt, J. S., Desportes, G., Breton-Honeyman, K., Christensen, T., Citta, J. J., Ferguson, S. H., Frost, K. J., Garde, E., Gavrilo, M., Ghazal, M., Glazov, D. M., Gosselin, J.-F., Hammill, M., Hansen, R. G., Harwood, L., Heide-Jørgensen, M. P., Inglangasuk, G., … Watt, C. A. (2019). Global Review of the Conservation Status of Monodontid Stocks. Marine Fisheries Review, 81(3–4), 53. https://doi.org/10.7755/MFR.81.3–4.1

Innes, S. and Stewart, R.E.A. (2002). Population size and yield of Baffin Bay beluga (Delphinapterus leucas) stocks. NAMMCO Scientific Publications, 4, 225–238. http://dx.doi.org/10.7557/3.2846

Innes, S., Heide-Jørgensen, M.P., Laake, J.L., Laidre, K.L., Cleator, H.J., Richard, P., and Stewart, R.E.A. (2002a). Surveys of belugas and narwhals in the Canadian High Arctic in 1996. NAMMCO Scientific Publications, 4, 169–190. http://dx.doi.org/10.7557/3.2843

Innes, S., Muir, D. C. G., Stewart, R. E. A., Heide-Jørgensen, M. P. and Dietz, R. (2002b). Stock identity of beluga (Delphinapterus leucas) in Eastern Canada and West Greenland based on organochlorine contaminants in their blubber. NAMMCO Scientific Publications, 4, 51–68. http://dx.doi.org/10.7557/3.2837

Jefferson, T.A., Karkzmarski, L., Laidre, K., O’Corry-Crowe, G., Reeves, R., Rojas-Bracho, L., Secchi, E., Slooten, E., Smith, B.D., Wang, J.Y. and Zhou, K. (2012). Delphinapterus leucas. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2014.2. Available at https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/13704/17691711

Kilabuk, P. (1998). A study of Inuit knowledge of the Southeast Baffin beluga. Report for the Southeast Baffin Beluga Management Committee. Nunavut Wildlife Management Board, Iqaluit, NT, 74. Available at https://www.nwmb.com/en/publications/southeast-baffin-beluga/1825-se-baffin-beluga-study

Kingsley, M. C. S. (2002). Status of the belugas of the St. Lawrence estuary, Canada. NAMMCO Scientific Publications, 4, 239–258. http://dx.doi.org/10.7557/3.2847

Koski, W.R., Davis, R.A. and Finley, K.J. (2002). Distribution and abundance of Canadian High Arctic belugas, 1974-1979. NAMMCO Scientific Publications, 4, 87–126. http://dx.doi.org/10.7557/3.2839

Kovacs, K. M., Lydersen, C., Overland, J. E., Moore, S. E. (2011) Impacts of changing sea-ice conditions on Arctic marine mammals. Marine Biodiversity, 41, 181-194. DOI 10.1007/s12526-010-0061-0

Laidre, K.L., Heide-Jørgensen, M.P., Jørgensen, O.A. and Treble, M.A. (2004). Deep-ocean predation by a high Arctic cetacean. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 61(3), 430–440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icesjms.2004.02.002

Lydersen, C., Martin, A.R., Kovacs, K.M. and Gjertz, I. (2001). Summer and autumn movements of white whales Delphinapterus leucas in Svalbard, Norway. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 219, 265–274. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps219265

Lydersen, C., Nøst, O.A., Lovell, P., McConnell, B.J., Gammelsrød, T., Hunter, C., Fedak, M.A. and Kovacs, K.M. (2002). Salinity and temperature structure of a freezing Arctic fjord – monitored by white whales (Delphinapterus leucas). Geophysical Research Letters, 29(3), 34-1–34-4. https://doi.org/10.1029/2002GL015462

Martineau D, Lemberger K, Dallaire A, Labelle P, Lipscomb TP, Michel P and Mikaelian I. (2002). Cancer in wildlife, a case study: beluga from the St. Lawrence Estuary, Quebec, Canada. Environmental Health Perspectives, 110, 285–292. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.02110285

McQuinn, I.H., Lesage, V., Carrier, D., Larrivee, G., Samson, Y., Chartrand, S., Michaud, R. and Theriault, J. (2011). A threatened beluga (Delphinapterus leucas) population in the traffic lane: Vessel-generated noise characteristics of the Saguenay-St. Lawrence Marine Park, Canada. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 130(6), 3661–3673. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.3658449

North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO). (2000). Report of the NAMMCO Scientific Committee Working Group on the Population Status of Narwhal and Beluga in the North Atlantic. In NAMMCO Annual Report 1999, 153–188. NAMMCO, Tromsø, Norway. Available at https://nammco.no/topics/annual-reports/

North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO). (2002a). Report of the Joint meeting of the Scientific Committee Working Group on the Population Status of Narwhal and Beluga in the North Atlantic and the Scientific Working Group of the Joint Commission on the Conservation and Management. In NAMMCO Annual Report 2001, 213–248. NAMMCO, Tromsø, Norway. Available at https://nammco.no/topics/annual-reports/

North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO). (2002b). Greenland Progress Report on Marine Mammal Research. In NAMMCO Annual Report 2001, 279–282. NAMMCO, Tromsø, Norway. Available at https://nammco.no/topics/annual-reports/

North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO). (2003). Greenland Progress Report on Marine Mammal Research. In NAMMCO Annual Report 2002, 291–295. NAMMCO, Tromsø, Norway. Available at https://nammco.no/topics/annual-reports/

North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO). (2004). Greenland Progress Report on Marine Mammal Research. In NAMMCO Annual Report 2003, 319–322. NAMMCO, Tromsø, Norway. Available at https://nammco.no/topics/annual-reports/

North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO). (2005a). Report of the twelfth meeting of the Scientific Committee. In NAMMCO Annual Report 2004, 207–278. NAMMCO, Tromsø, Norway. Available at https://nammco.no/topics/annual-reports/

North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO). (2005b). Report of the thirteenth meeting of the Scientific Committee. In NAMMCO Annual Report 2005, 161–310. NAMMCO, Tromsø, Norway. Available at https://nammco.no/topics/annual-reports/

North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO). (2009). Norway Progress report on marine mammal research in 2006 and 2007. In NAMMCO Annual Report 2007-8, 337–366 NAMMCO, Tromsø, Norway. Available at https://nammco.no/topics/annual-reports/

North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO). (2010). Report of the sixteenth meeting of the Scientific Committee. In NAMMCO Annual Report 2009, 237–456. NAMMCO, Tromsø, Norway. Available at https://nammco.no/topics/annual-reports/

North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO). (2012a). Report of the 19th Scientific Committee Meeting, Tasiilaq, Greenland. Available at https://nammco.no/topics/scientific-committee-reports/

North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO). (2012b). Report of the NAMMCO Expert Group Meeting to Assess the Hunting Methods for Small Cetaceans, Copenhagen, Denmark. Available at https://nammco.no/topics/expert-group-meetings/

North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO). (2017). Report of the NAMMCO-JCNB Joint Scientific Working Group on Narwhal and Beluga, 8–11 March, Copenhagen, Denmark. Available at https://nammco.no/topics/sc-wg-reports/

North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO). (2018). Report of the NAMMCO Global Review of Monodontids meeting (GROM), 13–16 March, Hillerød, Denmark. Available at https://nammco.no/topics/report-global-review-monodontids-now-available/

North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO). (2021a). Report of the 27th meeting of the NAMMCO Scientific Committee. Tromsø, Norway: NAMMCO. Available at https://nammco.no/topics/scientific-committee-reports/

North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO) (2021b). Report from the Management Committee for Cetaceans. March, 2021. Tromsø, Norway: NAMMCO. Available at https://nammco.no/topics/mc_reports/

NAMMCO-JCNB Joint Working Group (NAMMCO-JCNB JWG) (2020). Report of the Joint Working Group Meeting of the NAMMCO Scientific Committee Working Group on the Population Status of Narwhal and Beluga in the North Atlantic and the Canada/Greenland Joint Commission on Conservation and Management of Narwhal and Beluga Scientific Working Group. October, 2020. Tromsø: Norway. Available at: https://nammco.no/topics/sc-wg-reports/

O’Corry-Crowe, G. M. (2018) Beluga Whale: Delphinapterus leucas. Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals, 3, 93-96.

O’Corry-Crowe, G., Lydersen, C., Heide-Jørgensen, M.P., Hansen, L., Mukhametov, L.M., Dove, O. and Kovacs, K.M. (2010). Population genetic structure and evolutionary history of North Atlantic beluga whales (Delphinapterus leucas) from West Greenland, Svalbard and the White Sea. Polar Biology, 33, 1179–1194. https://doi.org/10.1029/2002GL015462

O’Corry-Crowe, G. M., Suydam, R. S., Rosenberg, A., Frost, K. J., Dizon, A. E. (1997). Phylogeography, population structure and dispersal patterns of the beluga whale Delphinapterus lecuas in the western Nearctic revealed by mitochondrial DNA. Mol. Ecol., 6, 955-970. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-294X.1997.00267.x

Palsbøll, P. J., Heide-Jørgensen, M. P. and Bérubé, M. (2002). Analysis of mitochondrial control region nucleotide sequences from Baffin Bay belugas (Delphinapterus leucas): detecting pods or sub- populations? NAMMCO Scientific Publications, 4, 39–50. http://dx.doi.org/10.7557/3.2836

Richard, P.R. (2005). An estimate of the Western Hudson Bay beluga population size in 2004. DFO Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat, Res. Doc. 2005/17.Available at http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/csas-sccs/publications/resdocs-docrech/2005/2005_017-eng.htm

Richard, P.R., Heide-Jørgensen, M.P., Orr, J.R., Dietz, R. and Smith, T.G. (2001). Summer and autumn movements and habitat use by belugas in the Canadian High Arctic and adjacent areas. Arctic, 54(3), 207–222. https://doi.org/10.14430/arctic782

Sejersen, F. (2001). Hunting and management of beluga whales (Delphinapterus leucas) in Greenland: Changing strategies to cope with new national and local interests. Arctic, 54(4), 431–443. https://doi.org/10.14430/arctic800

Sharpe, M. & Berggren, P. 2023. Delphinapterus leucas (Europe assessment). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2023: e.T6335A219012513. Accessed on 19 December 2023.

Smith T.G and Hammill M.O. (1986). Population estimates of white whale, Delphinapterus leucas, in James Bay, Eastern Hudson Bay, and Ungava Bay. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 43(10), 1982–1987. https://doi.org/10.1139/f86-243

Stewart, R.E.A., Campana, S.E., Jones, C.M. and Stewart, B.E. (2006). Bomb radiocarbon dating calibrates beluga (Delphinapterus leucas) age estimates. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 84(12), 1840–1852. https://doi.org/10.1139/z06-182

Thiemann, G. W., Iverson, S. J., Stirling, I. (2008). Polar bear diets and arctic marine food webs: Insights from fatty acid analysis. Ecological Monographs, 78, 4, 591-613. https://doi.org/10.1890/07-1050.1

Turgeon, J., Duchesne, P., Colbeck, G.J., Postma, L.D. and Hammill, M.O. (2012). Spatiotemporal segregation among summer stocks of beluga (Delphinapterus leucas) despite nuclear gene flow: implication for the endangered belugas in eastern Hudson Bay (Canada). Conservation Genetics, 13, 419–433. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10592-011-0294-x

Vacquié-Garcia, J., Lydersen, C., Marques, T.A., Andersen, M. and Kovacs, K.M. 2020. First abundance estimate for white whales Delphinapterus leucas in Svalbard, Norway. Endangered Species Research 41, 253-263.

Wenzel, G.W. (1995). Ningiqtuq: Resource sharing and generalized reciprocity in Clyde River, Nunavut. Arctic Anthropology, 32(2), 43–60. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40316386?seq=1