Risso’s Dolphin

April 2020

Risso’s dolphin is a globally distributed species that is found in the temperate and tropical offshore zones of all oceans, typically at water depths of 400-1000 m. With a blunted head, crescent melon and a large stocky body heavily patterned with white scars, Risso’s dolphins have distinct features compared to other Delphinidae species, making them easy to recognise.

The species is a visitor rather than a resident species to the cooler waters of NAMMCO member countries.

ABUNDANCE

There are no estimates of global abundance for the species, but Risso’s dolphins are considered abundant in most of their distribution area. On the European continental shelf, the abundance is estimated to be approximately 11,000 individuals, with highest densities off eastern Ireland and north-western Scotland.

DISTRIBUTION

Risso’s dolphins are widely distributed in both hemispheres in tropical to temperate oceans. They are predominantly found in water depths of 400-1000m along the continental shelf edge and slope.

RELATION TO HUMANS

There is no history of commercial hunt of Risso’s dolphins in the North Atlantic.

CONSERVATION AND MANAGEMENT

In the eastern North Atlantic, the populations show no evidence of significant decline, although population abundance and trends have not been quantified thoroughly.

IUCN lists the species as “Least Concern” on both global (2018) and European Red List (2023).

Risso’s dolphins are protected in the North Atlantic. It is not a resident species in the waters of NAMMCO member countries and no assessment effort has been dedicated to the species to date.

Scientific name: Grampus griseus

Faroese: Risso’s springari

Greenlandic: As the species is rare in this area, no common name has been given

Icelandic: Höfrungur rissós

Norwegian: Arrdelfin

Danish: Risso’s delfin

English: Risso’s dolphin, grey dolphin

Lifespan

Risso’s dolphins reach more than 40 years of age.

Size

Adult Risso’s dolphins reach a size of 360-400 cm and weigh 300-500 kg.

Productivity

Breeding and calving may occur year-round. Females give birth to a single calf after a gestation period lasting 13 to 14 months.

Movements

The species is not known for undertaking large migrations, but they do travel within their local distribution area in search of areas where prey is abundant.

Feeding

In the North Atlantic, Risso’s dolphins prey mainly on squid, octopus and cuttlefish. The primary prey species varies across the distribution range.

General Characteristics

As the fifth largest member of the Delphinidae family, adult Risso’s dolphins reach up to four metres in length and weigh up to half a tonne. This makes it the largest dolphin species. Males and females are around the same size.

The basic body structure of this species resembles other oceanic dolphins although it is considerably stockier. The extremely robust anterior body tapers to a narrow tail. With a blunt face, a crescent melon and no distinct beak, the species differs significantly from typical Delphinidae and is easily distinguished from other species. The dorsal fin is one of the tallest in proportion to body length of any cetacean, with the exception of adult male killer whales.

Jumping Risso’s dolphin © Peter Evans.

Another highly distinctive feature of Risso’s is the heavily scarred grey pigmentation of the adults. The nuance of the grey base colouration changes throughout their lifetime. They are born with a silvery grey colour, turn pale-grey as juveniles, are dark-brown or black as subadults and become paler on the abdomen, head and sides until almost white in adult individuals, particularly males. The discolouration in adult specimens is a result of distinctive linear scars accumulated over time. The origin of the scarring is not certain, but probably a result of social interaction (Hartman 2018, MacLeod 1998). Some of the marks are also scratches from the beaks and suction cups of cephalopod prey. The species have a whitish anchor-shape coloration patch on the chest between the flippers, which resembles that of pilot whales.

Risso’s dolphins have no teeth in the upper jaw but between two and seven pairs of peg-like teeth in the lower jaw, which is an unusual feature for a dolphin species. The teeth have little or no function for foraging, as the species is specialised in cephalopod hunting and swallow their prey whole. Researchers hypothesise that Risso’s dolphins use their teeth mostly in and for social interactions with conspecifics, which is thought to be the cause of the criss-cross scarring pattern on the animals. Some scarring is usual in cetaceans, however the extent that it appears in Risso’s dolphins is unusual.

Risso’s dolphins © Peter Evans.

The name Grampus griseus is of Latin descent. The exact meaning of Grampus is not clear but is thought to originate from grandis piscis which translates to grand or big fish. Griseus refers to the mottled grey colouration of the species.

Essentially nothing is known about the population structure of this species. However, genetic studies suggest that Risso’s dolphin populations are genetically differentiated throughout their distribution range (Gaspari, Airoldi and Hoelzel 2006). The differentiation between populations is also supported by the distinctness found in whistle characteristics between individuals from the Mediterranean and British waters (Benoldi et al. 1999).

Taxonomy

Within the Delphinid family, the species is closest related to false killer whale (Pseudoorca crassidens), melon headed whale (Peponocephala electra), pygmy killer whale (Feresa attenuata) and pilot whale (Globicephala sp) (Hartman et al. 2018).

Did you know?

Risso’s dolphin have one of the largest dorsal fins in comparison to their body size. This has caused observers to confuse them with killer whales and sharks when seen from afar.

Life History and Ecology

Life History

Adults probably reach sexual maturity at a length of about 2.8m, and the females at 8-10 years of age (Whitehead and Mann 2000) and males between 10-12 years years of age (Bloch et al. 2012, Hartman 2018).

In mature males, the testicular mass represents 3% of the total body mass (Bloch et al. 2012). Based on this large size of the testes, it is believed that Risso’s dolphins have a promiscuous mating system in which females mate with multiple males in a single oestrus period.

Risso’s dolphins calve year-round. In the North Atlantic, calving peaks in the summer between March and July (Evans 2008, Hartman et al. 2014, Pereira 2008). Females gives birth to a single calf born with a mean size of 1.3 m (Whitehead and Mann 2000). The lactation period lasts between 2 and 3 years (Amano and Miyazaki 2004, Bloch et al. 2012).

The lifespan of Risso’s dolphins is not known, but growth rings (growth layer groups) in their teeth indicate that they can reach more than 40 years of age. The oldest reproducing female ever recorded was 38 years old, and age determination using scar accumulation suggest lifespans of 45-50 years in some individuals (Bloch et al. 2012, Hartman et al. 2016, Kruse 1999, Taylor et al. 2007).

Social Interactions

Risso’s dolphins form pods of various sizes throughout their distributional range. In European waters, they gather in pods of 2-50 individuals, with smaller group sizes in British waters compared to Spanish and Italian waters (Evans 2008, Gaspari et al. 2008, Gómez de Segura et al. 2008).

Several Risso’s dolphins together © Peter Evans

Overall, for the European populations, research on gene flow suggests a fluid social structure. Surveillance of individuals recognised by photo-identification of unique morphological traits (Photo-ID) suggests some stable bonds between non-related individuals within the pods, based on age and sex (Hartman et al. 2008). Pod size and spatial distribution varies with the presence of calves. Groups with new-born and nursing calves tend to be larger and closer to shore in the Azores (Hartman et al. 2014).

Group composition in Faroese, Japanese and Azorean waters (Amano and Miazaki 2004, Bloch et al. 2012, Hartman et al. 2008, 2014) suggests age and sex-stratified social structure. In a pod landed in the Faroes, 71% of the individuals were females, of which 67% were mature. There was an equal number of immature males and females, but only 17% of adult individuals were males (Bloch et al. 2012). Young individuals of both sexes may leave the natal school after weaning and adult males are segregated from mature females.

A significant amount of – aggressive – interactions between individuals of the species takes place, as evidenced by the heavily scarred body surface and discolouration that is particularly visible in mature/older individuals. This is likely caused by the loss of pigment during the healing process of skin wounds caused by the teeth (MacLeod 1998). The scarring intensity of a male may function as an indicator of “male quality” or dominance, thus decreasing the need for aggressive behaviour within groups/pods and contributing to stability (Hartman et al. 2008, MacLeod 1998).

Sound/Communication

Risso’s dolphins may use echolocation to a lesser extent than other odontocetes with a similar-sized melon. The different structure of the melon and the number of bioluminescent prey species in stomach contents suggests that Risso’s dolphins may rely on their sight when foraging, using bioluminescence as a target (Bloch et al. 2012, Öztürk 2007). However, a trained Risso’s dolphin was observed using echolocation in a similar way to that of other dolphins, although the clicks emitted were of slightly lower amplitude and frequency (Phillips et al. 2003). The use of echolocation in the species therefore remains to be fully investigated and established.

Diving and Swimming

Risso’s dolphin jumping @ Peter Evans

In the North Atlantic, there is little knowledge about the behaviour of Risso’s dolphins. The species is usually cautious around vessels, making behavioural studies difficult. During the daytime, the species usually seems to travel, socialise or rest, while most feeding occurs at night (Smultea et al. 2018).

Breaching happens at low swimming speed with occasional jumping behaviour. They are known to tail slap and spy hop among other social activities, and in some areas of their distribution, they bow ride (Hartman et al. 2008). Although considered relatively slow swimmers (4-12 km/h at cruise speed), Risso’s dolphins will travel at speeds of 20-25 km/h when frightened or evading vessels (Evans 2008, Kruse et al. 1999).

Risso’s dolphins have also been observed showing different kinds of interspecific behaviour (interacting with other species). In the Azores, Risso’s dolphins have been observed harassing other odontocete species such as sperm whales, which also forage on the same squid species (Pereira 2008).

In the waters of the coast of the Lewis Hebrides in the UK, researchers’ observations suggest that Risso’s dolphins hybridise with other species, e.g. the bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) (Hodgins, Dolman and Wier 2014).

Food and Feeding

In the North Atlantic, Risso’s dolphins feed on both pelagic and benthic species of squid, octopus and cuttlefish (Bloch et al. 2012). They dive down to about 800m depth in their search for prey (Whitehead 2003). Findings of bioluminescent squid species, such as flying squid (Todarodes sagittatus), veined squid (Loligo forbesi), and the benthic octopus (Eledona cirrhosa) in the stomach contents of stranded specimens indicates that Risso’s dolphins hunt at night or at least at twilight. This would allow them to prey on the mesopelagic squid and fish that inhabit deep waters but rise with the deep scattering layer (DSL) at night (Bearzi et al. 2010, Soldevilla et al. 2010, 2011, Jefferson et al. 2015).

Predators

It is likely that Risso’s dolphins are preyed upon by sharks and orcas in areas where they share habitat.

Health – diseases and parasites

There is essentially no knowledge on the diseases and parasites that affect Risso’s dolphins. Since they seldom strand, have little to no history of a commercial hunt, and have an offshore habitat information on their general health is difficult to gather.

Strandings

Most strandings of Risso’s dolphins involve single individuals, although one mass stranding in southern Peru has been documented (Garcìa-Godos and Cardich 2011).

Did you know?

Risso’s dolphin lack teeth in the upper jaw but have up to seven pairs of conical teeth in the lower jaw, which is a very unusual feature for a dolphin species.

Distribution and habitat

Distribution

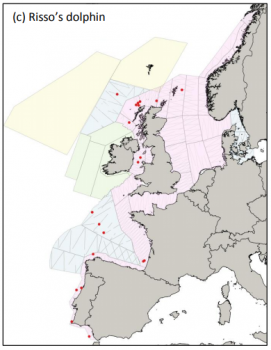

Risso’s dolphins are found in tropical and temperate waters across both hemispheres (Jefferson et al. 2014). The species’ preferred temperature range is 15-25°C, although it is also found in waters between 7.5 – 28°C (Evans 2008, Wells et al. 2009). The abundance and distribution of the species is also determined by prey abundance more than water depth.

Risso’s dolphin jumping out of the water © Peter Evans

In the North Atlantic, the Risso’s dolphin is an occasional visitor in the cooler waters of NAMMCO member countries. Its northern most distribution boundaries are south of Newfoundland in the west to southern Norway in the east. In the 1980s, several observations were made in the Trondheimsfjord (64° N) and the species came into the national species list (Sundnes, 1988), however the species is still considered a rare visitor to Norway (Syvertsen et al. 2010). According to a citizens science observation platform, published on the Ocean Biogeographic Information Systems website (ORBIS 2020) Risso’s dolphins have been observed even further North into Northern Norway and around Iceland.

Until August 2009, the most northerly record of Risso’s dolphins in the middle Northeast Atlantic was at 60° 23′ N. The more recent observations from the Faroe Islands and further North could indicate a northward extension of the species (Bloch et al. 2012, Syvertsen et al. 2010). Increasing water temperature might induce this larger distributional range (MacLeod 2009).

Habitat

Risso’s dolphins are primarily found on the continental slope and outer shelf (400-1000 m) in areas where the topography of the bottom is steep (Hartman 2018, Jefferson et al. 2014), as well as in oceanic areas (beyond the 2,000 m depth contour). They tend to occur in deep waters (Hammond et al. 2017, Jefferson et al. 2014), but can be found close to shore, where the continental slope is steep near the coast as it is in the Mediterranean (Azzellino et al. 2008, Praca and Gannier 2007). Interestingly, Risso’s dolphins are also found in the shallow waters around the UK, where they inhabit waters of 30-40m depth and right up to 7 m depth, such as in the English Channel, (Kiszka et al. 2004, 2007), the Celtic Sea (Reid et al. 2003) and the Irish Sea. A population of more than 100 animals frequent the shallow waters off Bardsey Island, North Wales (DeBoer et al. 2013), which is surprising behaviour for this oceanic species.

Movements and Migration

The Risso’s dolphin is not considered a migratory species and is present year-round across most of its range. In their northernmost distributional areas, however, Risso’s dolphins might undertake seasonal migration. It is, for example, more abundant around northern Scotland in the summer than in the winter (Evans 1998).

The species is believed to have some degree of residency within their distributional range. In some waters, Risso’s dolphins express site fidelity (animals revisit or stay in the same location over time) as is seen around the Azores (Hartman 2015, 2018, Visser 2014).

Abundance and Stocks

Worldwide

There are only regional/local abundance estimates for Risso’s dolphins and therefore no estimate of global abundance for this species.

North Atlantic

Risso’s dolphin sightings during SCANS III (Hammond et al. 2017)

There are no overall estimates for the abundance of Risso’s dolphins in the North Atlantic. In the Northeast Atlantic, the aerial SCANS-III survey carried out in summer 2016 generated an abundance of around 11,000 individuals in the waters of the European continental shelf (Hammond et al. 2017). Currently, population trends in European waters are not known (Evans 2008) and more research on distribution and abundance is crucial.

In the Northwest Atlantic, the best estimate in U.S. waters comes from surveys conducted in 2011, which estimated about 18,000 individuals (Hayes et al. 2016), with an additional 1,589 in the northern Gulf of Mexico based on surveys in 2003 and 2004 (Waring et al. 2011).

Management

The species is protected by all NAMMCO member countries. The species is protected by law in Norway, the Faroe Islands and Greenland, and the hunting of Risso’s dolphins is illegal in Iceland. As the Risso’s dolphin is not a resident species in the waters of NAMMCO member countries, no assessment effort has been dedicated to the species within NAMMCO to date.

With a global “Least Concern” IUCN listing (Kiszka and Braulik 2018), no reported population declines, or major threats identified, Risso’s dolphins receive little management and conservation attention in Europe. Researchers call for more information to establish a management plan for this species at both regional and global levels.

Species Status in Europe

Risso’s dolphin is listed as “Not Applicable” on the Norwegian National Red List, due to the vagrant nature of the species in the Northeast Atlantic, and it is not mentioned on the Greenlandic or Icelandic National Red Lists.

IUCN Red List:

Global: Least Concern 2018 (Kiszka and Braulik 2018).

European: Data Deficient 2007 (Species account by IUCN SSC Cetacean Specialist Group 2007).

Mediterranean: Data Deficient 2010 (Gaspari and Natoli 2012).

The North, Baltic and Mediterranean Seas populations are included in Appendix II of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS, Bonn Convention). This covers migratory species that have an unfavourable conservation status and require international agreements for their conservation and management, as well as those that have a conservation status that would significantly benefit from the international cooperation that could be achieved by an international agreement.

The species is listed in Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). This includes species not necessarily threatened with extinction, but in which trade must be controlled in order to avoid utilisation incompatible with their survival.

Risso’s dolphins are covered by the Agreement on the Conservation of Small Cetaceans of the Baltic, North East Atlantic, Irish and North Seas (ASCOBANS) and the Agreement of the Conservation of Cetaceans of the Black Sea, Mediterranean Sea and Contiguous Atlantic Area (ACCOBAMS).

The Risso’s dolphin is mentioned in Appendix II of the Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats (Bern Convention). This convention aims to ensure conservation of wild flora and fauna species and their habitats. Special attention is given to endangered and vulnerable species, including endangered and vulnerable migratory species specified in appendices.

It is also listed, as all European cetaceans, in Annex IV of the EU Habitats Directive (1992), which lists the species and sub-species for which a strict protection regime must be applied across their entire natural range within the EU, both within and outside Natura 2000 sites.

Risso’s dolphins are furthermore on the original UK Biodiversity Action Plan priority species list of 2007. The Scottish Government has listed the Risso’s dolphin as Priority Marine Features, warranting marine protected areas (MPAs) (Dolman et al. 2013 – in ECS 2013). It is also a species of principal importance in Wales (UK; S.42under section 42 of the Natural Environment and Rural Communities Act (NERC) 2006.

DID YOU KNOW?

A Risso’s dolphin named Pelorus Jack became famous for guiding boats across Cook’s Strait in New Zealand between 1888 and 1912. It sparked the first government protection for a cetacean after someone fired a rifle at the curious dolphin in 1904. The Scottish ceilidh dance Pelorus Jack is named after this famous dolphin.

Human impacts

Human Removals: Hunt / By-catch

Hunt

The species is protected in the North Atlantic and therefore not subject to direct hunt. However, Risso’s dolphins were intentionally taken in two separate incidents in 2009 and 2010 in the Faroe Islands by an opportunistic drive fishery (Bloch et al. 2012).

In other areas, Risso’s dolphins are considered a food resource and are taken intentionally or as by-catch. In Sri Lanka, the species was the third most hunted cetacean during the 1980s. This may have affected the abundance of the population in the area (Jefferson et al. 1993) as surveys have suggested a possible decline of Risso’s Dolphins off Sri Lanka, particularly along the south coast (Anderson 2013). Risso’s dolphins are taken regularly by hand harpoon and driving, in set nets, and as a limited catch in the small-type whaling industry, with reported catches in recent years ranging from about 250–500 (Kasuya 2018, Kiszka and Braulik, 2018).

By-catch

The threat from by-catch is generally believed to be low for Risso’s dolphins in the Northeast Atlantic. There are observations of by-catch in the Mediterranean Sea in longline and gillnet fisheries. Risso’s dolphins have been reported as being by-caught in pelagic longline fisheries, which they are particularly susceptible to since they regularly depredate squid used as bait (Kiszka 2015). They have also been reported as by-catch in large-mesh driftnets for large pelagic fish in many areas of the world (for a review see Kiszka and Braulik, 2018).

Noise / Disturbance

Like other deep divers such as beaked whales, Risso’s dolphins are likely to be affected by disturbance from noise from various anthropogenic sources such as that generated by military sonar and seismic surveys. (Southall et al. 2016, Modest 2015). The extent of the effect of anthropogenic noise on Risso’s dolphins is still unclear and research on the issue is important as significant military exercises occur in North Atlantic waters.

Recreational disturbance, however, has also become of increasing concern in recent years. Whale watching and “swim-with” tours, which are significant activities in the Azores and some parts of Italy, pose a threat to this species. Research has revealed significant altered resting patterns when whale watching vessels are present in the area (Visser et al. 2011, Hartman et al. 2014).

Contaminants

Little is known of contaminant levels in Risso’s dolphins in the North Atlantic. In the Mediterranean, Risso’s dolphins (like other odontocete species) carry high levels of contaminants, which is also the case in several regions of the Pacific (Chou, Chen and Li 2004, Kruse et al. 1999, Marsili and Focardi 1997, Kim et al. 1996). In addition, foreign materials such as plastic and metal have been documented in the stomachs of stranded specimens in Japan (Frodello et al. 2000).

Climate Change

For Risso’s dolphins, the most likely impact from global warming within the North Atlantic will be changes to their distributional range due to the increasing water temperature (Evans and Bjørge 2012, MacLeod 2009). Recently, observations suggest an extension of the range northwards to Faroese waters (Bloch et al. 2012). The species is now recorded in the northern North Sea on a regular basis. This is likely linked to cephalopods having become abundant in areas where they used to be rare (Evans and Bjørge 2012).

Amano, M. & Miyazaki, N. (2004). Composition of a school of Risso’s dolphin, Grampus griseus. Marine Mammal Science, 20, 152-160. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2004.tb01146.x

Anderson, R. C. (2013). Risso’s dolphin (Grampus griseus): impact of the Sri Lankan tuna gillnet fishery. Working Party on Ecosystems and Bycatch (WPEB). Indian Ocean Tuna Commision. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Available at: IOTC-2013-WPEB09-30.

Azzellino, A., Gaspari, S., Airoldi, S., & Nani, B. (2008). Habitat use and preferences of cetaceans along the continental slope and the adjacent pelagic waters in the western Ligurian Sea. Deep-Sea Research I, 55, 296-323.

Bearzi, G., Reeves, R. R., Remonato, E., Pierantonio, N. & Airoldi, S. (2011). Risso’s dolphin Grampus griseus in the Mediterranean Sea. Mammalian Biology, 76(4), 385-400. doi: doi.org/10.1016/j.mambio.2010.06.003

Benoldi, C., Gill, A., Evans, P. G. H., Manghi, M., Pavan, G., & Priano, M. (1999). Comparison between Risso’s dolphin vocal repertoire in Scottish waters and in the Mediterranean Sea. European Research on Cetaceans, 12, 235-239.

Bloch, D., Desportes, D., Harvey, P., Lockyer, C. and Mikkelsen, B. (2012), Life History of Risso’s Dolphin (Grampus griseus) in the Faroe Islands. Aquatic Mammals 2012, 38(3), 250-266. doi:10.1578/AM.38.3.2012.250

Chou, C. C., Chen, Y. N. & Li, C. S. (2004). Congener-Specific Polychlorinated Biphenyls in Cetaceans from Taiwan Waters. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 47, 551–560. doi:10.1007/s00244-004-3214-y

DeBoer, M., Clark, J.,., Lepold, M. F., Simmonds, M., & Reijnders, P. J. H. (2013). Photo-Identification Methods Reveal Seasonal and Long-Term Site-Fidelity of Risso’s Dolphins (Grampus griseus) in Shallow Waters (Cardigan Bay, Wales). Open Journal of Marine Science, 3, 65-74. doi:10.4236/ojms.2013.32A007

Dolman et al. (2013). In, Chen, I., Hartman, K., Simmonds, M., Wittich, A. and Wright, A. J. (Eds.). Grampus griseus 200th anniversary: Risso’s dolphins in the contemporary world. Report from the European Cetacean Society Conference Workshop, Galway, Ireland. European Cetacean Society Special Publication Series, 54, 108 pages.

Evans, P. G. H. (1998), Biology of cetaceans in the North-East Atlantic (in relation to seismic energy). In M L Tasker & C Weir, (Eds.) Proceedings of the Seismic and Marine Mammals Workshop, London 23-25 June 1998, Sea Mammal Research Unit, U of St. Andrews, Scotland.

Evans, P. G. H. (2008). Risso’s dolphin, Grampus griseus. In S. Harris & D. W. Yalden (Eds.), Mammals of the British Isles: Handbook (4th ed., pp. 740-743). Southampton, UK: The Mammal Society.

Evans, P. G. H. & Bjørge, A. (2012). Impacts of climate change on marine mammals. Marine Climate Change Impacts Partnership (MCCIP) Annual Report Card 2011-2012 Scientific Review, 1-26. doi:10.14465/2013.arc15.134-148

Frodello, J.P., Romeo, M., Viale, D. (2000). Distribution of mercury in the organs and tissues of five toothed-whale species of the Mediterranean. Environmental Pollution, 108, 447–452.

García-Godos, I. & Cardich, C. (2011). First mass stranding of Risso’s dolphins (Grampus griseus) in Peru and its destiny as food and bait. Marine Biodiversity Records, 3. doi:10.1017/S1755267209991084.

Gaspari, S., Airoldi, S & Hoelzel, R. (2006). Risso’s dolphins (Grampus griseus) in UK waters are differentiated from a population in the Mediterranean Sea and genetically less diverse. Conservation Genetics. 8. 727-732. doi:10.1007/s10592-006-9205-y.

Gaspari, S. & Natoli, A. 2012. Grampus griseus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2012: e.T9461A3151471.

Genov, T. 2023. Grampus griseus (Europe assessment). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2023: e.T9461A218567526. Accessed on 22 December 2023.

Gómez de Segura, A., Crespo, E., Pedraza, S., Hammond, P., Raga, J. (2006). Abundance of small cetaceans in waters of the central Spanish Mediterranean. Marine Biology, 150, 149–160.

Hammond, P.S., Lacey, C., Gilles, A., Viquerat, S., Börjesson, P., Herr, … Øien, N. (2017). Estimates of cetacean abundance in European Atlantic waters in summer 2016 from the SCANS-III aerial and shipboard surveys. Wageningen Marine Research. Available from: St. Andrews University.

Hartman, K. L., Visser, F., and Hendriks, A. J. E. (2008). Social structure of Risso’s dolphins (Grampus griseus) at the Azores: a stratified community based on highly associated social units. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 86, 294 -306.

Hartman, K. L., Fernandez, M., & Azevedo, J. M. N. (2014). Spatial segregation of calving and nursing Risso’s dolphins (Grampus griseus) in the Azores, and its conservation implications. Marine Biology, 161(6), 1419-1428. doi:10.1007/s00227-014-2430-x

Hartman, K.L., Fernandez, M., & Azevedo, J. M. N. (2015). Sex differences in residency patterns of Risso’s dolphins (Grampus griseus) in the Azores: Causes and management implications, Marine mammal Science, 31(3) doi:10.1111/mms.12209

Hartman, K.L. (2018). Risso’s dolphin. In B Würsig, J. G. M., Thewissen, & K. M. Kovacs (Eds.). Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals, (Third edition., pp. 824-827), London, UK: Elsevier

Hayes, S. A., Josephson, E., Maze-Foley, K., and Rosel, P. E. (2016). US Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico Marine Mammal Stock Assessments – 2016. NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-NE-241. US: NOAA.

Hodgins, Nicola & Dolman, Sarah & Weir, Caroline. (2014). Potential hybridism between free-ranging Risso’s dolphins (Grampus griseus) and bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) off north-east Lewis (Hebrides, UK). Marine Biodiversity Records, 7, doi:10.1017/S175526721400089X.

Jefferson, T.A., Leatherwood, S. & Webber, M.A. (1993). FAO species identification guide. Marine mammals of the world. Italy, Rome: FAO. 152-153.

Jefferson, T.A., Weir, C.R., Anderson, R.C., Ballance, L.T., Kenney, R.D., Kiszka, J.J. (2014). Global distribution of Risso’s dolphin Grampus griseus: a review and critical evaluation. Mammal Review, 44(1). 56-68.

Kasuya, T. (2018). Japanese whaling. In. B. Würsig, J. G. M. Thewissen and K. M. Kovacs (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals, Third Edition, (pp. 1066-1070). UK, London: Academic Press.

Kim, G.B., Tanabe, S., Iwakir,i R., Tatsukawa, R., Amano, M., Miyazaki, N. & Tanaka, H. (1996). Accumulation of butyltin compounds in Risso’s dolphin (Grampus griseus) from the Pacific coast of Japan: Comparison with organochlorine residue pattern. Environmental Science and Technology, 30, 2620-2625. doi:org/10.1021/es9600486

Kiszka, J. (2015). Marine mammals: a review of status, distribution and interaction with fisheries in the Southwest Indian Ocean. In. R.P. Van der Elst and B.I. Everett (Eds). Offshore fisheries of the Southwest Indian Ocean: their status and the impact on vulnerable species (pp. 303-323). Durban, South Africa: Oceanographic Research Institute.

Kiszka, J. & Braulik, G. (2018). Grampus griseus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018: e.T9461A50356660. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T9461A50356660.en.

Kiszka, J., Hassani, S. and Pezeril, S. (2004). Status and distribution of small cetaceans along the French Channel coast: using opportunistic records for a preliminary assessment. Lutra, 47, 33-46.

Kiszka, J., Macleod, K., Van Canneyt, O., Walker, D. and Ridoux, V. (2007). Distribution, encounter rates, and habitat characteristics of toothed cetaceans in the Bay of Biscay and adjacent waters from platform-of-opportunity data. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 64, 1033-1043. doi:10.1093/icesjms/fsm067

Kruse, S., Caldwell, D. K., & Caldwell, M. C. (1999). Risso’s dolphin Grampus griseus (G. Cuvier, 1812). In S. H. Ridgway & R. J. Harrison (Eds.), Handbook of marine mammals. Vol. 6: River dolphins and the larger toothed whales (pp. 183-212). London: Academic Press.

MacLeod, C. D. (2009). Global climate change, range changes and potential implications for the conservation of marine cetaceans: a review and synthesis. Endangered Species Research, 7, 125-136. doi: 10.3354/esr00197

MacLeod, C. D. (1998). Intraspecific scarring in odontocete cetaceans: An indicator of male ‘quality’ in aggressive social interactions? Journal of Zoology, 244, 71-77. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1998.tb00008.x

Marsili, L. & Focardi, S. (1997). Chlorinated hydrocarbon (HCB, DDTs and PCBs) levels in cetaceans stranded along the Italian coasts: an overview. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment,45, 129-180. doi:1023/A:1005786627533

Modest, M. (2015). Anthropogenic noise pollution: understanding the effect of mid-frequency active sonar on Risso’s dolphin behavior. MSc thesis, Imperial College London.

Öztürk, B., Salman, A., Öztürk, A.A., Tonay, A. (2007). Cephalopod remains in the diet of striped dolphins (Stenella coeruleoalba) and Risso’s dolphins (Grampus griseus) in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Vie Milieu, 57, 53–59.

Pereira, J. N. D. S. G. (2008). Field notes on Risso dolphin (Grampus griseus) distribution, social ecology, behavior and occurrence in the Azores. Aquatic Mammals, 34, 426 – 435.

Philips, J. D., Nachtigall, P. E., Au, W. W. L., Pawloski, J. L., Roitblat, H. L. (2003). Echolocation in the Risso’s dolphin, Grampus griseus. The Journal of Acoustical Society of America, 113, 605-616. doi: 10.1121/1.1527964

Praca, E. & Gannier, A. (2008). Ecological niches of three teuthophageous odontocetes in the northwestern Mediterranean Sea. Ocean Science, 4, 49-59.

Reid, J.B., Evans, P. G. H. and Northridge S. P. (2003). Atlas of Cetacean distribution in north-west European waters., Peterborough, U.K: Joint Nature Conservation Committee.

Soldevilla, M. S., Wiggins, S. M. & Hildebrand, J. A. (2010). Spatial and temporal patterns of Risso’s dolphin echolocation in the Southern California Bight. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 127, 124-132.

Southall, B. L., Nowacek, D. P., Miller, P. J. & Tyack, P.L. (2016). Experimental field studies to measure behavioral responses of cetaceans to sonar. Endangered Species Research, 31, 293-313. doi: 10.3354/esr00764

Smultea, M. A., Lomac-MacNair, K., Nations, C. S., McDonald, T. & Würsig, B. (2018). Behavior of Risso’s Dolphins (Grampus griseus) in the Southern California Bight: An Aerial Perspective. Aquatic Mammals 2018, 44(6), 653-667. doi:10.1578/AM.44.6.2018.653

Species account by IUCN SSC Cetacean Specialist Group; regional assessment by European Mammal Assessment team. (2007). Grampus griseus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2007: e.T9461A12989112.

Sundnes, G. (1988). Rissodelfiner I Trondheimsfjorden [Rissodolphins in the Trondheimsfjord]. Fauna, 41(3), 104. (In Norwegian with abstract in English)

Syvertsen, P. O., Isaksen, K., Olsen, K. M., Ree, V., Solheim, R., & Wiig, Ø. (2010). New Norwegian names for mammals, with an updated national species list. Fauna, 63(2), 50-59.

Taylor, B. L., Baird, R., Barlow, J., Dawson, S. M., Ford, J., Mead, J. G., . . . Pitman, R. L. (2008). Grampus griseus. In IUCN red list of threatened species, Version 2010.4. Retrieved 5 July 2012 from www.iucnredlist.org.

Visser, F. (2014). Moving in concert: Social and migratory behaviour of dolphins and whales in the North Atlantic Ocean. PhD thesis. Available at: University of Amsterdam

Visser, F., Hartman, K. L., Rood, E. J. J., Hendriks, A. J. E., Zult, D. B., Wolff, W. I., Huis, J. & Pierce, G. J. (2011). Risso’s dolphins alter daily resting pattern in response to whale watching at the Azores. Marine Mammammal Science, 27, 366-381. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2010.00398.x

Waring, G. T., Josephson, E., Maze-Foley, K., and Rosel, P. E. (Eds). (2012). U.S. Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico Marine Mammal Stock Assessments – 2011. NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-NE-219. 330pp.

Wells, R.S., Manire, C.A., Byrd, L., Smith, D.R., Gannon, J.G., Fauquier, D.& Mullin, K.D. (2009). Movements and dive patterns of a rehabilitated Risso’s dolphin, Grampus griseus, in the Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic Ocean. Marine Mammal Science, 25, 420-429. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2008.00251.x

Whitehead, H. and Mann, J. (2000). Female reproductive strategies of cetaceans: life histories and calf care. In. J. Mann, R.C. Connor, P.L. Tyack, and H. Whitehead (Eds.). Cetacean societies. Field studies of dolphins and whales (219-246). US, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.