Striped Dolphin

Updated: April 2020

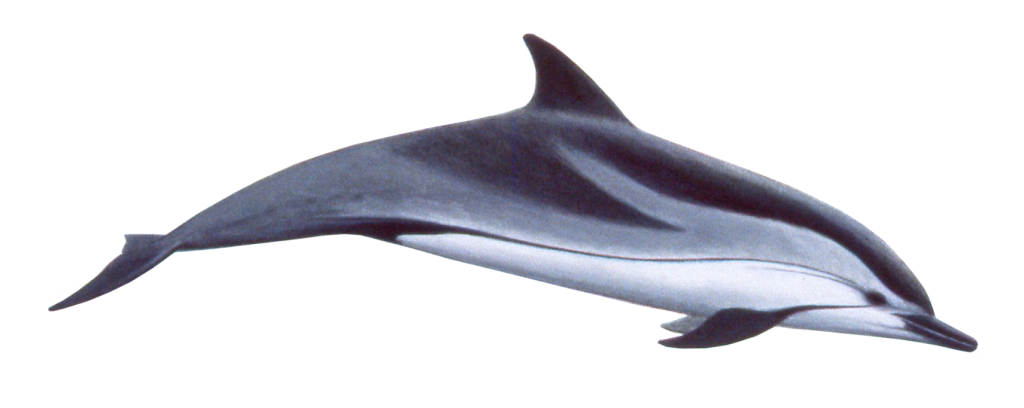

The striped dolphin is a globally distributed species that is mostly found offshore in tropical and subtropical waters. Built like most oceanic dolphin species, striped dolphins are known for their distinct and striking side colouration pattern, which includes a bold, thin stripe that originates at the beak, encircles the eyes and extends one branch down to the flipper and the other down the side of the body to the anal region. Above this black line, a wider brushstroke of blue/grey runs from head to tail, with a blaze running to the rear of the dorsal fin dividing the dark coloration of the back.

This unique coloration, combined with an acrobatic and gregarious behaviour, distinguishes the striped dolphin from other cetacean species.

The species is not a resident but a visitor in the waters of NAMMCO member countries.

Abundance

There are estimated to be more than 2 million striped dolphins on a global scale. In the North Atlantic they are in the top three most abundant cetacean species.

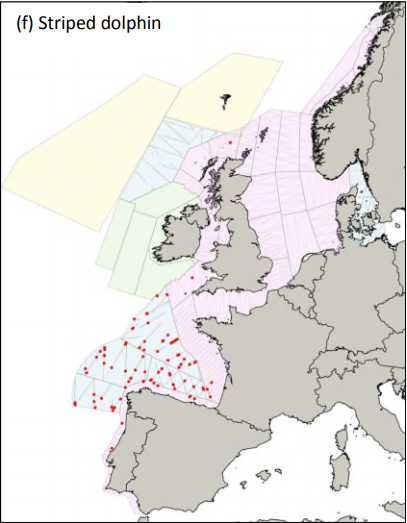

Distribution

Striped dolphins are distributed in tropical to warm temperate waters and are commonly found off the continental shelf and in up-welling areas. They are occasionally observed in the temperate Northeast Atlantic, with extralimital records at sea in southern Greenland, Iceland and the Faroe Islands. There have also been some strandings in Norway.

Relation to humans

There is no history of commercial hunt in the North Atlantic, although there is a small-scale hunt in the Caribbean today.

Conservation and management

The population of the eastern North Atlantic shows no evidence of decline, although abundance and trends have only been estimated in a few areas and there have been concerns about the level of by-catch by pelagic trawl and driftnet fisheries.

The IUCN lists the species as “Least concern” on both global (2019) and regional European Red List (2023).

The striped dolphin is protected in the North Atlantic. It is not a resident species in the waters of NAMMCO member countries, which is why no assessment effort has been dedicated to this species.

Scientific name: Stenella coeruleoalba

Faroese: Rípuspringari

Greenlandic: As the species is rare in this area, no common name has been given

Icelandic: Rákahöfrungur

Norwegian: Stripedelfin

Danish: Stribet delfin

English: Striped dolphin or Streakers

Lifespan

Striped dolphins have been estimated to live up to 58 years.

Size

Females reach a length of around 240 cm and males 260 cm. Adults of both sexes weigh between 150 – 160 kg.

Productivity

Females give birth to one calf every three to four years after a 12-14 month gestation period.

Movements

Striped dolphins do not undertake large migrations but rather tend to stay in areas where prey is abundant.

Feeding

In the North Atlantic, striped dolphins prey mostly on oceanic pelagic fish, particularly lanternfish and cod, down to 700m depth.

General Characteristics

Striped dolphin is a classic oceanic delphinid species. They have a long prominent clearly defined beak, a rounded forehead (melon) and long narrow flippers (pectoral fins). The dorsal fin has a typical sickled shape and is placed centrally on the back.

The back (or cape) and dorsal fin, tail (dorsal parts), flippers and beak are dark grey/black, while the underside (ventral side) is white to almost pinkish. A black stripe originating from the beak incircle the eyes and divides to run to the flippers and the anus. The distinctive marking is the brushstrokes of bluish or light grey running from the head towards the tail above the side bold stripe. It creates a contrasting shoulder blaze that curves back and up toward the animal’s dorsal fin and divide the dark coloration of the back. This unique coloration distinguishes the striped dolphin from other cetacean species and is the origin of its common name.

The highly aerial and gregarious behaviour of the striped dolphin associated to its striking and distinctive colour pattern, with usually large groups encountered, make the species easy to spot and recognise at sea.

Taxonomy

Striped dolphin belongs to the genus Stenella, consisting of five oceanic species: spinner dolphins (Stenella longirostris), spotted dolphins (Stenella frontalis and Stenella attenuata), clymene dolphin (Stenella clymene) and striped dolphins (Stenella coeruleoalba). The genus has, however, been found to be paraphyletic, which means that the Stenella genus includes the most recent common ancestor, but not all descendants. Therefore, the taxonomy for Stenella coeruleoalba, might be revised in the time to come (McGowen et al. 2009).

DID YOU KNOW?

The name coeruleoalba is the combination of the latin words coeruleo meaning blue and alba meaning white, which refers to the elaborate striped patterns in blue and white characterizing this species.

Life History and Ecology

Life History

Females reach a length of around 2.4 metres and males 2.6 metres and adults of both sexes weigh between 150 – 160 kg, with some regional variation. Striped dolphins are estimated to live up to 58 years (Archer and Perrin 1999). Females become sexually mature at 5-13 years and males at 7-15 years. Generally, individuals reach maturity when they are larger than 2 meters in length, which explains the large age span for maturity (Archer 2018).

The mating system of striped dolphin seems to vary between populations but overall is believed to be polygynous (polygamy), i.e., one male mating with several females, but females only mating with one male. After a gestation period of ca. one year (12-14 months), females give birth to a single calf in the summer or autumn, with a three- or four-year gap between calving in the reproductive cycle (Archer and Perrin 1999).

Social Interactions

Striped dolphins are a very social species. Groups/schools commonly consist of 10-30 individuals but can be up to several hundred and sometimes a thousand individuals of similar breeding status and age. Three different kinds of schools are generally observed across their distribution: juveniles, non-breeding adults, and breeding adults (Archer and Perrin 1999, Miyazaki and Nishiwaki 1978). When juveniles become mature, they either join a non-breeding or a breeding group depending on factors still to be understood (Archer and Perrin 1999).

Sound/Communication

As all other dolphins, striped dolphins are believed to communicate within their social groups using elaborate whistle and click sequences (Jefferson and LeDuc 2018). Like other cetaceans, they also use echolocation – a series of high frequency sounds to locate prey and orientate themselves underwater (Whitlow 2018). As striped dolphins feed down to depths of 700m, the ability to using echolocation is essential since lighting underwater below a few meters is minimal.

Diving and Swimming

Striped dolphins are highly conspicuous. They often appear in large groups, are fast swimming and often leap high above the surface. Their swimming behaviour is best described as athletic and energetic. They can perform leaps as high as 7 metres above the water, as well as tail spins and backward flips. They also generally travel at a steady pace up to 11km/h (Lafortuna et al. 1993).

They perform short dives between 5-10 minutes and will often dive several hundred metres in search of prey.

Food and Feeding

Most of the knowledge about the feeding habits of striped dolphins comes from the Bay of Biscay (Ringelstein 2006), the Mediterranean (Meissner et al. 2012) and the Pacific (Perrin et al. 2008). In the North Atlantic, their predominant prey item is lantern fish (Hassani et al. 1997, Archer 2018). However, across their distribution, striped dolphins feed on a variety of prey species found at various depths in the water column (mesopelagic and benthopelagic species), such as lanternfish (Myctophidae family), cod and squid, and in some areas, crustaceans.

Striped dolphins feed over the continental slope or oceanic regions, anywhere within the water column where prey is concentrated, and can dive at depths down to 700 metres.

Predators

Killer whales and sharks are the only species known as natural predators of striped dolphins (Archer and Perrin 1999).

Health – diseases and parasites

The most well documented disease in striped dolphins is the cetacean morbillivirus (CeMV, Van Bressem et al. 2009). The Mediterranean sub-population was devastated by severe outbreak of the disease in 1990-92 and 2006-2007, resulting in thousands of deaths and strandings.

It was later hypothesized, based on the first outbreak, that this sub-population was immunosuppressed due to extremely high concentrations of polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) and other organochlorine pollutants, and therefore stricken harder by the virus (Archer and Perrin 1999). However, data from the second event did not support that hypothesis (Castrillon et al. 2010).

Obductions of stranded specimens in British waters revealed various bacteria and vira as well as high pollutant loads, suggesting strandings and disease are correlated (Parsons et al. 2000, Davidson et al. 2014).

Strandings

Striped dolphins strand on a regular basis on the coasts of UK, Ireland and France, most often as single individuals or small groups (Spitz et al. 2006; Santos et al. 2008). However, two mass mortalities occurred in 1990-1992 and 2006-2007 in the Mediterranean, as mentioned above (Domingo et al. 1990, Archer and Perrin 1999).

Did you know?

Striped dolphins got their nickname “streakers” due to their increased swimming speed as they leave to avoid vessels in the Pacific.

Distribution and habitat

Distribution

Striped dolphins are primarily found in tropical to temperate oceanic waters around the globe (Jefferson et al. 1993). Their northern and southern range limits are about 50°N and 40°S. There are extralimital records from cooler boreal waters off Norway, Faroe Islands, Iceland and southern Greenland; the most northern observations of striped dolphins were made at the Kamchatka Peninsula, Prince Edward Island, Northern Norway and the Kola Peninsula (Bloch et al. 1996, Archer and Perrin 1999, Braulik 2019, OBIS 2019).

In the North East Atlantic, the species resides year-round around the British Isles and in the Bay of Biscay (MacLeod et al. 2009, Marcos et al. 2010).

Habitat

Throughout their range, the preferred habitat of striped dolphins is the deep oceanic waters of the continental shelf and slope. They may also be found in coastal areas where deep waters come close to shore. They are often found in upwelling areas or around convergence zones, where the associated high productivity creates favourable feeding opportunities (Balance et al. 2006). Their preferred water temperature range is 10-26°C, with most observations in waters between 18-22°C.

Movements and Migration

In the Atlantic, striped dolphins do not undertake extensive migration but rather tend to stay around areas where prey is abundant. They are therefore not considered a migratory species.

In the western Pacific, however, a distinctive migration pattern has been identified between South East Asian waters and Japan (Rudolph and Smeenk 2009).

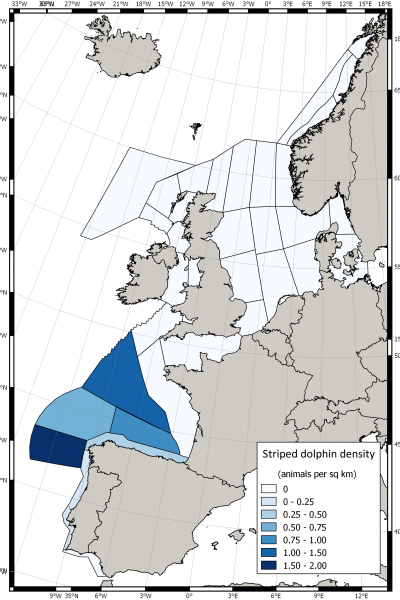

Abundance and Stocks

Worldwide

The population of striped dolphins is estimated to exceed 2 million individuals on a global scale.

North Atlantic

Aerial and ship-board line transect surveys of European Atlantic waters in the summer of 2016 generated an estimate of approximately 372,000 individuals (95% CI: 198,583 – 698,134) (Hammond et al. 2017). The striped dolphin was the third most abundant species recorded during the survey and was strongly concentrated in offshore waters (Hammond et al. 2017).

In the North West Atlantic, the total number of striped dolphins is unknown, but the best estimate for the region is about 54,800 (CV = 0.3) individuals from a 2011 survey (Waring et al. 2014).

Management

The species is protected by NAMMCO member countries. It is protected by law in Norway, the Faroe Islands and Greenland. In Iceland it is not permitted to hunt the species. The striped dolphin is not a resident species in the waters of NAMMCO member countries and therefore no assessment effort has been dedicated to the species within NAMMCO to date.

With a global “Least Concern” IUCN listing (Braulik 2019), no reported population declines, or major threats identified, the striped dolphin receives little management and conservation attention in Europe. However, by-catch is of concern in some areas. Overall, researchers call for more information to establish a management plan for this species both at regional and global levels.

Species Status in Europe

The species is listed as “Not Applicable” on both the Icelandic and Norwegian National Red list, due to its vagrant nature in these areas. It does not appear on the Greenlandic Red list.

IUCN Red List:

- Global: Least Concern in 2018 (Braulik 2019)

- European: Data Deficient in 2007 (IUCN 2007)

- Mediterranean: Vulnerable in 2010 (Aguilar and Gaspari 2012) because of population decline within the last 30 years.

The Mediterranean population is listed in Appendix II of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS, Bonn Convention), which covers migratory species that have an unfavourable conservation status and that require international agreements for their conservation and management, as well as those that have a conservation status which would significantly benefit from the international cooperation that could be achieved by an international agreement.

The species is listed in Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). This appendix includes species not necessarily threatened with extinction, but in which trade must be controlled in order to avoid utilisation incompatible with their survival.

The species is also mentioned in Appendix II of the Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats (Bern Convention), which aims to ensure the conservation of wild flora and fauna species and their habitats. Special attention is given to endangered and vulnerable species, including endangered and vulnerable migratory species specified in appendices.

It is listed, as all European cetaceans, on Annex IV of the EU Habitats Directive, which lists the species and sub-species for which a strict protection regime must be applied across their entire natural range within the EU, both within and outside Natura 2000 sites.

Striped dolphins are also covered by the Agreement on the Conservation of Small Cetaceans of the Baltic, North East Atlantic, Irish and North Seas (ASCOBANS) and the Agreement of the Conservation of Cetaceans of the Black Sea, Mediterranean Sea and Contiguous Atlantic Area (ACCOBAMS).

Human impacts

Human Removals: Hunt / By-catch

Hunt

Striped dolphins are not subject to direct hunt in the North East Atlantic today. They are, however, a food resource in the Caribbean in the West Atlantic. The species is also currently used as a food resource in Sri Lanka and Japan, with the latter accounting for most of the takes (Robards and Reeves 2011). In Sri Lanka and the Caribbean, the hunt is mainly for subsistence purposes (Kasuya 2017, Ilangakoon et al. 2000, Perrin et al. 1994).

Historically, the species was caught and used for human consumption in Italy, the Philippines, Trinidad and Tobago, St.Vincent and the Grenadines, St.Lucia and the Solomon Islands between 1970 – 2009, in Ukraine between 1990-2009 and in Portugal and Taiwan between 1970 – 1989 (Robards and Reeves 2011). They were also hunted for use as bait for shrimp traps and longlines and to supply food for consumption on board fishing vessels. Illegal catches occurred in southern Spain and probably in other areas up until, at least, the mid 2000’s (Aguilar 2006).

By-catch

The species is susceptible to by-catch throughout its range. However, more research is needed to establish the frequency and extent. Bycatch has been reported in gillnets and large pelagic tuna driftnets in the Northwest Atlantic (Rogan and Mackay 2007) and Mediterranean as well as in trawls, purse seines, longlines and various other fishing gear in the Pacific and other areas of their range (Archer 2018).

Particularly during the 1990’s, by-catch in pelagic trawl and driftnet fisheries was a source of concern for the striped dolphin population in western European waters (Tregenza and Collet 1998). In a study on marine megafauna mortality rates based on an observer program focused on a driftnet fishery in the eastern North Atlantic in 1996 and 1998, the number of landings of albacore tuna was used to extrapolate the number of by-caught dolphins for the period 1990-2000. This study estimated that out of 24,358 dolphins killed, 12,635 (10,009–15,261) were striped dolphins (Rogan and Mackey 2007).

Noise / Disturbance

Like for many other marine mammal species, disturbance from noise pollution can pose a threat to striped dolphins. As individuals are dependent on sound for both orientation (by echolocation) and communication, noise disturbance can disrupt their natural behaviour.

However, responses to noise and disturbances may differ between populations. Mediterranean striped dolphins are known to bow ride (Würsig 2018). In contrast, the Pacific striped dolphin flees at high speed from approaching vessels – a behaviour that gave them their nickname “streakers”. Behavioural responses to vessels can therefore vary and the effect of noise disturbance remains to be thoroughly investigated in striped dolphins, both at individual and population levels.

Contaminants

Striped dolphins, as many other odontocetes, show high accumulation rates of contaminants. In the Mediterranean, the population has a tissue level of organochlorine compounds beyond what is safe for mammals (Aguilar 2000, Storelli et al. 2012). Around Japan, extremely high concentrations of heavy metals, DDT and PCB’s have been documented as well (Tanabe et al. 1983). High levels of organochlorine compounds possibly cause immunosuppression, which lowers the natural resistance to disease outbreaks (Desforges et al. 2016).

In addition, contamination from plastic debris, oil spills and dumping of industrial wastes, can lead to bioaccumulation of a range of toxic substances in body tissues of marine mammals. Most contaminants degrade slowly, if at all, and concentration can therefore continuously build up in marine mammals and cause serious health issues (Reijnders et al. 2009).

Climate Change

Climate change will affect cetacean species in various ways according to their distribution and temperature requirements. For some there may be positive impacts (e.g. a widening of the possible geographical distribution) while for others it will be negative (particularly Arctic species for which suitable habitat can shrink due to rising temperatures and loss of sea ice). The consequences for the striped dolphin are not clear, but the changes in ocean temperatures may extend their distribution northwards.

Aguilar, A. (2000). Population biology, conservation threats and status of Mediterranean striped dolphins (Stenella coeruleoalba). Journal of Cetacean Research and Management, 2, 17-26. https://archive.iwc.int/pages/search.php?search=%21collection15&k=

Aguilar, A. (2006). Striped dolphin (Stenella coeruleoalba), mediterranean subpopulation. In. R. R. Reeves and G. Notarbartolo di Sciara (eds.), The status and distribution of cetaceans in the Black Sea and Mediterranean Sea, 57-63. IUCN Centre for Mediterranean Cooperation.

Aguilar, A. and Gaspari, S. (2012). Stenella coeruleoalba Mediterranean subpopulation. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2012: e.T16674437A16674052. https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2012-1.RLTS.T16674437A16674052.en

Archer, F. I. (2018). Striped dolphin. In B. Würsig, J. G. M Thewissen and K. M. Kovacs (eds.), Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals (3rd ed., pp. 954-956), London, UK: Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-804327-1.00251-X

Archer, F. I. and Perrin, W.F. (1999). Stenella coeruleoalba. Mammalian Species, 603, 1-9. https://doi.org/10.2307/3504476

Balance, L. T., Pitman, R. L. and Fiedler, P. C. (2006). Oceanographic influences on seabirds and cetaceans in the eastern tropical Pacific: A review. Progress in Oceanography, 69, 360-390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pocean.2006.03.013

Braulik, G. (2019). Stenella coeruleoalba. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2019: e.T20731A50374282. https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-1.RLTS.T20731A50374282.en

Bloch, D., Deportes, G., Petersen, A. and Sigirjøansson, J. (1996). Strandings of striped dolphins (Stenella coeruleoalba) in Iceland and the Faroe Islands and sightings in the Northeast Atlantic, North of 50○N latitude. Marine Mammal Science, 12(1), 125-132. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.1996.tb00310.x

Castrillon, J., Gomez-Campos, E., Aguilar, A., Berdie, L. and Borrell, A. (2010). PCB and DDT levels do not appear to have enhanced the mortality of striped dolphins (Stenella coeruleoalba) in the 2007 Mediterranean epizootic. Chemosphere, 81, 459-463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2010.08.008

Davison, N. J., Barnett, J. E. F., Koylass, M., Whatmore, A. M., Perkins, M. W., Deaville, R. C. and Jepson, P. D. (2014). Helicobacter cetorum infection in striped dolphin (Stenella coeruleoalba), Atlantic white-sided dolphin (Lagenorhynchus acutus), and short-beaked common dolphin (Delphinus delphus) from the southwest coast of England. Journal of Wildlife Diseases, 50(3), 431-437. doi:10.7589/2013-02-047

Desforges, J. P., Sonne, C., Levin, M., Siebert, U., De Guise, S. and Dietz, R. (2016). Immunotoxic effects of environmental pollutants in marine mammals. Environment International, 86, 126-139. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2015.10.007

Domingo M., Ferrer L., Pumarola, M. and Marco, A. (1990). Morbillivirus in dolphins. Nature, 348(21). doi: 10.1038/348021a0

Genov, T. 2023. Stenella coeruleoalba (Europe assessment). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2023: e.T20731A219009389. Accessed on 22 December 2023.

Hammond, P. S., Lacey, C., Gilles, A., Viquerat, S., Börjesson, P., Herr, … and Øien, N. (2017). Estimates of cetacean abundance in European Atlantic waters in summer 2016 from the SCANS-III aerial and shipboard surveys. University of St. Andrews. https://synergy.st-andrews.ac.uk/scans3/files/2017/05/SCANS-III-design-based-estimates-2017-05-12-final-revised.pdf

Hassani, S., Antoine, L. and Ridoux, V. (1997). Diets of albacore, Thunnus alalunga, and dolphins, Delphinus delphis and Stenella coeruleoalba, caught in the northeast Atlantic albacore drift-net fishery: a progress report. Journal of Northwest Atlantic Fishery Science, 22, 119-124. doi: 10.2960/J.v22.a10

Ilangakoon, A. D., Miththapala, S. and Ratnasooriya, W. D. (2000). Sex ratio and size range of small cetaceans in the fisheries catch on the west coast of Sri Lanka. Vidyodaya Journal of Science, 9, 25-35.

International Whaling Commission (IWC). (1998). Report of the scientific committee. Report of the International Whaling Commission, 48, 53-302.

Jefferson, T. A., Leatherwood, S. and Webber, M. A. (1993). FAO species identification guide. Marine mammals of the world. Rome, Italy: FAO.

Jefferson, T. A. and LeDuc, R. (2018). Delphinids overview. In B. Würsig, J. G. M. Thewissen and K. M. Kovacs (eds.), Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals (3rd ed., pp. 242-246). London, UK: Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-804327-1.00101-1

Kasuya, T. (2017). Small Cetaceans of Japan: Exploitation and Biology. US: CRC Press. 476 pp. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781315395425

Lafortuna, C. L., Jahoda, M., Notarbartolo-Di-Sciara, G. and Sabiene, F. (1993). Respiratory pattern in free-ranging striped dolphins. In P. G. H. Evans (eds.), Proceedings of the seventh annual conference of the European Cetacean Society (pp. 241-246). Cambridge: European Cetacean Society, 306 pp.

MacLeod, C., Brereton, T. and Martin, C. (2009). Changes in the occurrence of common dolphins, striped dolphins and harbour porpoises in the English Channel and Bay of Biscay. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 89(5), 1059-1065. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-373553-9.00205-4

Marcos, E., Salazar, J. M. & de Stephanis, R. (2010). Cetacean diversity and distribution in the coast of Gipuzkoa and adjacent waters, southeastern Bay of Biscay. Munibe (Ciencias Naturales-Natur Zientziak), 58, 221-231.

McGowen, M. R., Spaulding, M. and Gatesy, J. (2009). Divergence date estimation and a comprehensive molecular tree of extant cetaceans. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 58, 891-906. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2009.08.018

Meissner, A., MacLeod, C. D., Richard, P., Ridoux, V. and Pierce, G. (2012). Feeding ecology of striped dolphins, Stenella coeruleoalba, in the north-western Mediterranean Sea based on stable isotope analyses. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 92. doi:10.1017/S0025315411001457.

Moore, S. E. (2018). Climate Change. In B. Würsig, J. G. M. Thewissen and K. M. Kovacs (eds.), Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals (3rd ed., pp. 194 – 197). London, UK: Elsevier. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128043271000923

Miyazaki, N. and Nishiwaki, M. (1978). School structure of the striped dolphin off the Pacific coast of Japan. Scientific Reports of the Whales Research Institute, 30, 65-115.

Parsons, E. C. M., Shrimpton, J. and Evans, P. G. H. (2000). Cetacean Conservation in Northwest Scotland: Perceived threates to ceataceans. European Research on Cetaceans 13, 128 – 133.

Perrin, W. F., Robertson, K. and Walker, W. (2008). Diet of the Striped Dolphin, Stenella coeruleoalba, in the Eastern Tropical Pacific Ocean. Publications, Agencies and Staff of the U.S. Department of Commerce. available at: digitalcommons.unl.edu

Perrin, W. F., Wilson, C. E. and Archer, F. I. (1994). Striped dolphin Stenella coeruleoalba (Meyen, 1833). In S. H. Ridgway and R. Harrison (eds.), Handbook of marine mammals, Volume 5: The first book of dolphins (pp. 129-159). Academic Press.

Reijnders, P. J. H., Aguilar, A. and Borrell, A. (2009). Pollution. In B. Würsig, J. G. M Thewissen and K. M. Kovacs (eds.), Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals (3rd ed., pp. 746-752), London, UK: Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-804327-1.00202-8

Ringelstein. J., Pusineri, C., Hassani, S., Meynier, L., Nicolas, R. and Ridoux, V. (2006). Food and feeding ecology of the striped dolphin, Stenella coeruleoalba, in the oceanic waters of the north-east Atlantic. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 86, 909-918. doi:10.1017/S0025315406013865

Robards, M. D. and Reeves, R. R. (2011). The global extent and character of marine mammal consumption by humans: 1970–2009. Biological Conservation, 144(12), 2770-2786. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2011.07.034.

Rogan, E. and Mackay, M. (2007). Megafauna bycatch in drift nets for albacore tuna (Thunnus alalonga) in the NE Atlantic. Fisheries Research, 86(1), 6-14. doi:10.1016/j.fishres.2007.02.013

Rudolph, P. and Smeenk C.(2009). Indo-West Pacific Marine Mammals. In W. F Perrin, B. Würsig. and J. G. M. Thewissen (eds.), Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals (2nd ed., pp. 608-616). London, UK: Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-373553-9.00142-5

Santos, M. B., Pierce, G. J., Learmonth, J. A. and Ried, R. J. (2008). Strandings of striped dolphin Stenella coeruleoalba in Scottish waters (1992 – 2003) with notes on the diet of this species. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 8(6), 1175-1183. doi:10.1017/S0025315408000155

Spitz, J. Richard, E. Meynier, L. Pusineri, C. and Ridoux, V. (2006). Dietary plasticity of the oceanic striped dolphin. Stenella coeruleoalba, in the neritic waters of the Bay of Biscay. Journal of Sea Research, 55(4), 309-320. doi:10.1016/j.seares.2006.02.001

Storelli, M. M., Barone, G., Giacominelli-Stuffler, R. and Marcotrigiano, G. O. (2012). Contamination by polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) in striped dolphins (Stenella coeruleoalba) from the Southeastern Mediterranean Sea. Environmental monitoring and assessment, 184, 1269-1275. doi:10.1007/s10661-011-2382-2

Tanabe, S., Mori, T., Tatsukawa, R. and Miyazaki, N. (1983). Global pollution of marine mammals by PCBs, DDTs, and HCHs (BHCs). Chemosphere, 12, 1269-1275. doi:10.1016/j.seares.2006.02.001

Tregenza, N. J. C. and Collet, A. (1998). Common dolphin Delphinus delphis bycatch in pelagic trawl and other fisheries in the North East Atlantic. Reports of the International Whaling Commission, 48, 453-459. doi:10.1016/0045-6535(83)90132-7

Van Bressem, M. F., Raga, J., Di Guardo, G., Jepson, P., Duignan, P., Siebert, U., … and Van Waerebeek, K. (2009). Emerging infectious diseases in cetaceans worldwide and the possible role of environmental stressors. Diseases of aquatic organisms, 86, 143-57. doi:10.3354/dao02101.

Waring, G. T., Josephson, E., Maze-Foley, K., Rosel, P. E., Cole, T. V., Engleby, L., … Orphanides, C. (2014). U.S. Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico marine mammal stock assessments, 2013. NOAA Technical Memorandum. NOAA-TM-SWFSC-228. U.S. Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Marine Fisheries Service, Northeast Fisheries Science Center.

Whitlow W. L Au. (2018). Echolocation. In B. Würsig, J. G. M Thewissen and K. M. Kovacs (eds.). Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals (3rd ed., pp. 298-299). London, UK: Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-804327-1.00113-8

Würsig, B. (2018). Bow-riding. In B. Würsig, J. G. M Thewissen and K. M. Kovacs, (Eds.). Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals (3rd. ed., pp. 135-136). London, UK: Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-804327-1.00076-5