Blog: Getting to know a new group

I am sure we have all been there before…We arrive at a meeting, workshop, seminar, or course and the host invites us to take a round of introductions to get to know each other. One by one we go around the room with everyone saying their name, position, institute and something about their area of interest or expertise. Except, almost everyone is thinking about what they are going to say rather than listening to what others are saying and typically, no one remembers any of the details.

In professional environments, this approach to getting to know a new group is so common that it is almost as if we have forgotten that there might be other ways to establish connections and learn about one another.

One of my roles as Lead Facilitator for the 4th cohort of Homeward Bound (HB4) was to design and run the exercises we would do when the participants first came together. This included just before the welcome dinner which was held on the first night, as well as the opening session of the first day with program content. The women had already spent 11 months receiving HB leadership training in a virtual space and had therefore started to get to know each other through a range of platforms, constellations and conversations. However, the welcome dinner and the opening day of program delivery would be the first time that the whole group was physically together in the same space.

In this blog post I will describe the opening exercises I used to help the 100 women of HB4 get to know each other in those first moments of meeting. These exercises were crucial for preparing them for living and working together in the complex, contained and cross-cultural environment that was our 3 week voyage to Antarctica. I share this information in the hope that others organising professional meetings might also become interested in experimenting with the range of approaches available for getting to know a new group beyond performing the standard round of introductions.

Breaking the Ice

On the first night, HB4 hosted a welcome dinner for all participants. Of course, with 100 women it was never going to be possible to do a traditional round of introductions. So, before the participants were let into the dining room, I was given 15 minutes with the group milling about in the foyer to begin the process of encouraging them to get to know each other. Although there are lots of great icebreaker exercises out there (see here for some examples), 15 minutes is not a very long time to work with a group of 100, so I had to think very carefully about what we were trying to achieve in those opening moments.

In the wonderful book, The Art of Gathering: How we meet and why it matters, Priya Parker emphasises the importance of thinking about the purpose of your gathering and designing the various elements and aspects accordingly. She also emphasises the significance of both the opening and closing moments. Taking her lessons to heart, I noted that the aim we had for the first 15 minutes before their shared dinner was to make them feel welcome as part of the group, to try and get them to relax enough to start having conversations with one another, and to feel comfortable enough to approach anyone and everyone. However, I was also very aware that I needed to maintain the energy and excitement of the group given the adventure we were about to embark on. This meant I needed to open the gathering in such a way that the participants felt relaxed, but not too relaxed!

With this in mind, I first asked the participants to shout out how they were feeling, repeating over the microphone the words that I heard. This helped to immediately make clear the overall mood of the group. It also worked to demonstrate that many people were feeling the same things – nervous, excited, hungry, tired from travelling etc. With this simple exercise, we quickly established how the group was feeling and highlighted that many people felt the same way. This helped create a sense of commonality and all being in this experience together.

I then asked the participants to find someone they thought was different from them and introduce themselves. After allowing a few minutes for conversation, I brought the group back together and asked them to shout out what characteristics they had used to identify difference. This not only worked to get them talking to someone ostensibly different from themselves, but also demonstrated the range of answers, approaches and ways we have of thinking about both our similarities and differences.

Thirdly, I asked them to find someone they had not met before and have a conversation that did not involve what they did or where they were from. This encouraged them to find non-standard modes of starting conversations with a new person and to approach others in the room as having complex and interesting lives beyond their work and place of residence. After a few minutes of conversation, I again brought them back as a group and asked them to shout out what kind of things they had asked and learned about. This highlighted a range of possible conversation starters that the group as a whole could use throughout the rest of the night.

By using these different questions and exercises in the first 15 minutes of our gathering, we managed to quickly establish the group’s mood, get participants talking to one another, break down barriers, and generate ideas for possible conversation starters. Following this, motivational music began blaring from the dining room and the participants were let into the room to share their first dinner together.

Introducing Myself & Our Hand Signals

The start of the following day – our first day delivering program content in person – was another important moment for the opening of our gathering.

To start this day, I began by giving them an overview of the plan for the morning, ran my first 5 minute “check-in” meditation (see previous post for more information) and gave my ‘Symposium at Sea’ (S@S). The HB S@S is something all participants are asked to do during the voyage. It involves delivering a talk about yourself and your work in 3 minutes and 2 slides. This was my opportunity to tell the group about who I was and how I wanted to work as their Lead Facilitator.

Following my S@S, I introduced some hand signals to help the group communicate – both with me and each other. Everyone is familiar with the signal of raising their hand when they want to say something in a professional setting. In addition to this classic signal, I also invited the group to use “jazz hands” (open hands waving back and forth) to signal when they agreed with something. This is a really effective way for people in large groups to show their support for something as soon as it is said (without waiting to be given the word) and for those speaking to actually see this support immediately. I also introduced an L symbol (made by the thumb and first finger) that participants could use to specifically request clarification on language. When working in multi-cultural and multi-disciplinary groups, it is really important to have the possibility to easily ask for these types of clarifications. Having a hand signal specifically for this purpose can also help destigmatise a lack of understanding around terminology, jargon or slang

Another hand signal that HB uses regularly is that of one arm raised high in the air as a call for silence. When 100 fiercely intelligent and deeply motivated women are chatting, on break or while engaged in an exercise, it can be really difficult to call them back into quiet focused attention. In HB, when you see someone with their arm in the air, you are requested to stop talking and raise your own arm. This signalling quickly spreads through the room and silence typically falls within less than a minute. This was such an effective way to gain the group’s attention that even the expedition staff starting using it when they wanted to communicate with us.

The Orientation Map

Following the introduction to who I was and how I wanted to work as their Lead Facilitator, it was important to begin finding out more about who the participants were. For this, I began by running an orientation exercise.

In this exercise, I placed a compass on the screen and asked the participants to position themselves in the room according to where they were born. To do this, they had to talk to each other, find out where they were from and then place themselves in relation to what they learned. This exercise allowed the group to have a visual map of our global distribution (by birth) as well as to see and meet those who came from the same country, region or language group as them.

After highlighting some of the features of our distribution by birth, I asked people to move and orient themselves according to where they lived now. This second round allowed us to see the mobility of the group, how many people live in different places from where they were born, and where the majority of our participants were based now. It also highlighted a couple of nomads who jogged around the room without stopping anywhere in particular!

Finally, I asked the participants to move to a place that felt like home. This was to recognise that home is not necessarily where you were born or where you live now. Once repositioned in this way, I asked them to talk to others nearby about the landscape (plants, animals, features) of that place and how this had shaped who they were. This specific invitation was to encourage them to begin thinking about the agency of the land to affect who we are. This was a particularly important aspect to establish before we introduced Antarctica as our 13 faculty member.

The Spectrum Line

After the orientation map exercise, I had all the participants line up single file across the room for an exercise I called the spectrum line. In this exercise, I really wanted to highlight the potential for very different opinions within the group on some basic things that could affect our living and working together. For example, different preferences regarding scheduling, punctuality, and how to deliver feedback.

In her book The Culture Map, Erin Meyer highlights that although some of the different ways people like to work are based on individual differences, culture can also impart different preferences for certain ways of thinking, organising and communicating. Inspired by this work, I designed the spectrum line exercise to map the group’s diversity according to 4 of Meyer’s categories: scheduling, communicating, disagreeing and evaluating.

Using paired statements, I asked the participants to step left from the single file line if they leaned more towards the first statement, and right if they leaned more towards the second. With the possibility to take one or multiple steps depending on how strongly they felt about the issue. This created a visual map of how the group varied across the spectrum of possible responses on these topics. The statements I used in this spectrum line exercise were:

Scheduling:

- It is rude if someone arrives 10 minutes late to a scheduled work meeting without an excuse or explanation

- It is okay if someone arrives 10 minutes late to a scheduled work meeting without an excuse or explanation

Communicating:

- Good communication is simple, direct, explicit, to the point, and repetitive if necessary

- Good communication is nuanced, layered, implied, requires some reading between the lines

Disagreeing

- Disagreement and debate are healthy and constructive when working in a group

- Disagreement and debate are detrimental and destructive when working in a group

Evaluating

- Negative feedback is best delivered honestly and directly

- Negative feedback is best delivered softly and subtly

After everyone had stepped left or right and taken their position on the questions for each topic, I highlighted the importance of the divergence in the group and what it meant in terms of how we should behave towards one another for the next 3 weeks on the ship (before asking them to step back into line for the next set of statements).

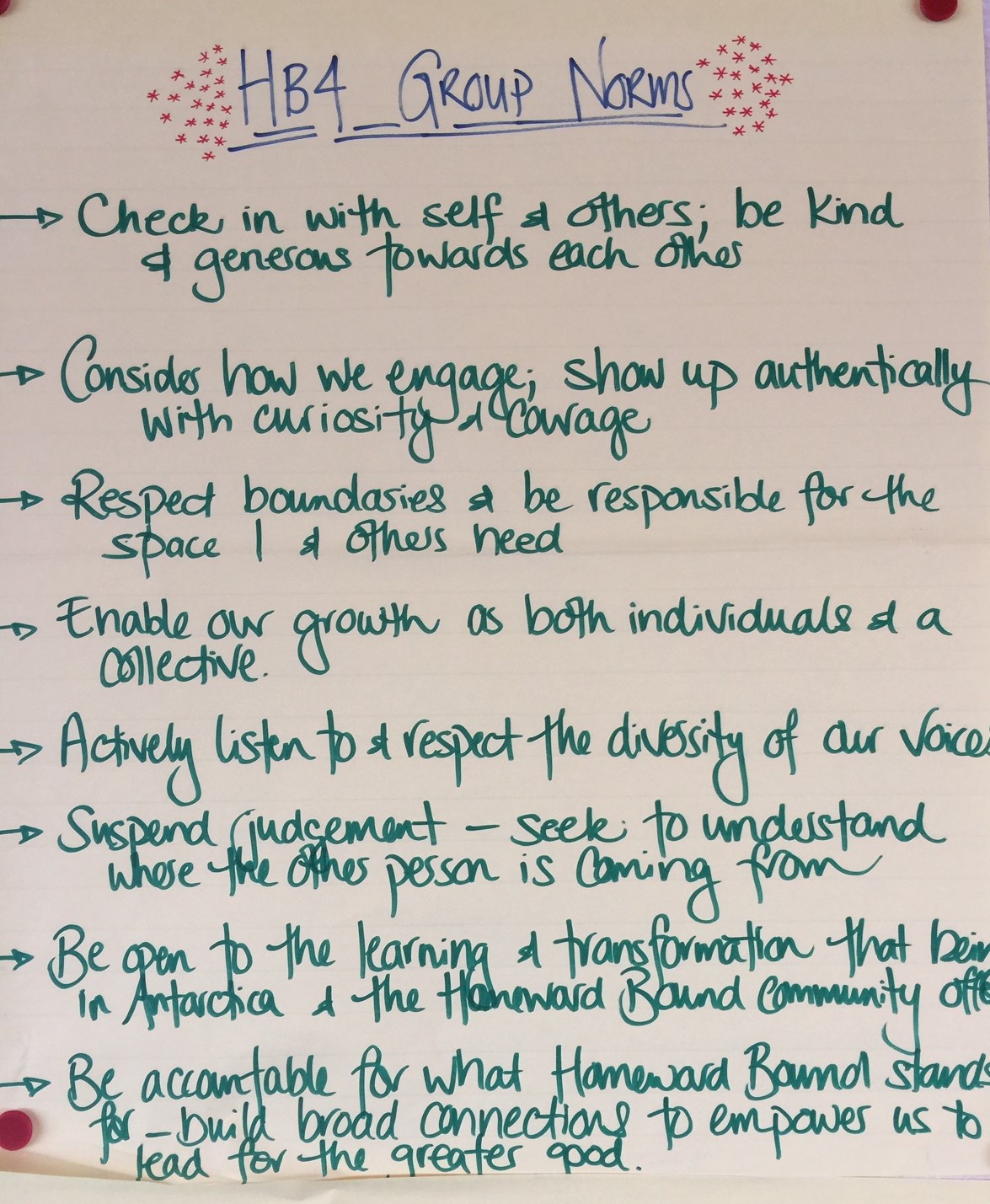

Group Norms

The final piece of the program that I ran on the first day was not just about getting to know each other better but also to establish how we wanted to be together in the intense environment of living and working on the ship for the next three weeks – particularly given the different preferences the spectrum line revealed. We did this by taking time to establish a set of group norms – an agreement on how the group would behave together.

For HB4, we spent considerable time developing these norms. Inspired by the work of Brené Brown, this included having the participants first build a courage container by answering the following questions (first individually and then discussing their answers within small groups): 1. What brought you here? 2. What are your fears/concerns about the group? 3. What would a successful experience look like for you? 4. What support do you need from this group to do the work? 5. What boundaries need to be put in place for you to feel safe?

After spending time in small groups working to turn their answers to these questions into norms for how the group would behave, I introduced them to the work Brené Brown has done on building trust through BRAVING. Braving is an acronym she uses for what she calls the 7 elements of trust: Boundaries, Reliability, Accountability, Vault, Integrity, Non-judgement, and Generosity. She talks about these elements of trust in terms of braving with self and braving with others. After the participants had time to reflect on their emerging norms in the context of BRAVING and make any additions or amendments they felt necessary, we began to share the group norms from each table in plenary. After hearing from all the tables, the faculty synthesised the common elements into a single set of norms.

These shared group norms then hung at the front of the room for the rest of our time together. They were regularly referred to by both participants and faculty and really helped shape the way the group interacted with one another.

Creating and facilitating these different ice breaker and get to know you exercises was an important part of my role in the first few days. These exercises were crucial for establishing the early tone of the experience and how the participants would relate to one another. It was really important that we used these opening moments of our gathering to facilitate both the group getting to know each other better and to build appreciation and respect for their diversity before we began living and working in the complex, contained and cross-cultural environment of our 3 week voyage to Antarctica.

And thank goodness we did not have to rely on a stale round of introductions to do it!

In the next blog post about my work as Lead Facilitator for HB4, I will talk more about the major content piece I delivered on board the ship. This was a two-part session on what happens when science meets ethics and politics in environmental decision-making.

By Fern Wickson