Blue whale

Updated: August 2025

The blue whale is a cosmopolitan species. It is found in all the major oceans of the world and has a tendency to remain in deep waters. It is the largest of the baleen whales and also the largest animal to have ever lived.

The blue whale appears lighter in colour than most other large whales. It has a bluish grey mottled pigmentation with light and dark patches.

The average size of blue whales in the Northern Hemisphere is 24–28 m, with an average weight between 50 and 150 tonnes. Females are slightly larger than males. Their spout can reach up to 12 m and their vocalizations can be heard for hundreds of kilometres. Despite their large size, blue whales feed almost exclusively on tiny krill.

ABUNDANCE

There are more than 3,000 blue whales in the Central and Eastern North Atlantic and their numbers are increasing (NAMMCO 2018b, Pike et al. 2019).

DISTRIBUTION

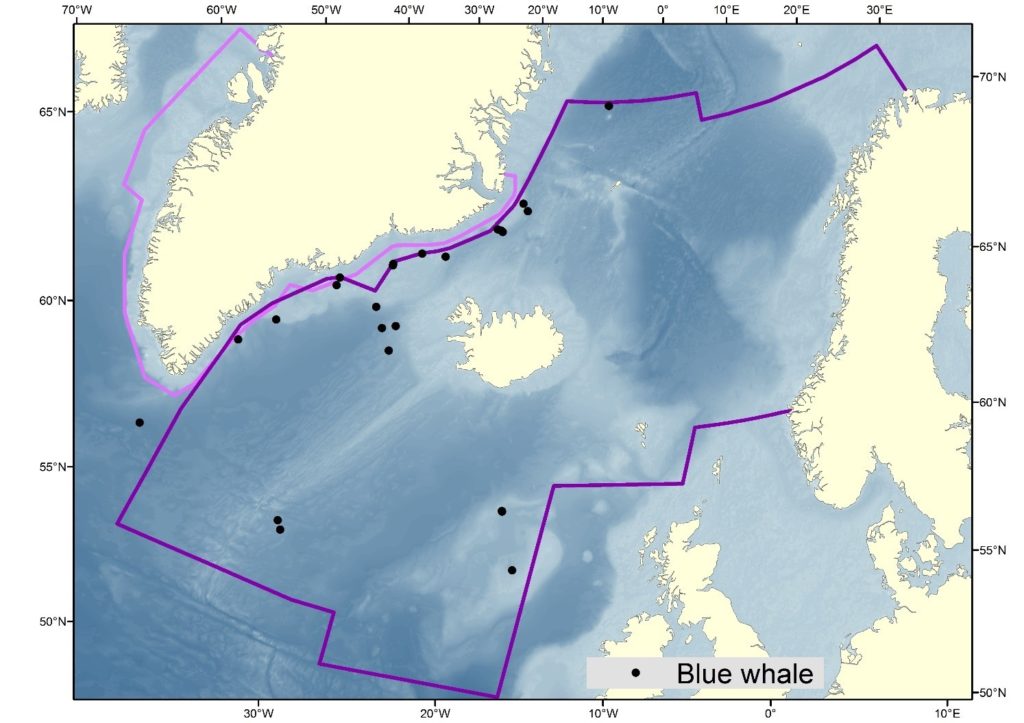

In the North Atlantic, blue whales are most frequently found around west and north Iceland. They can also be found around Jan Mayen and Svalbard, as well as along the coast of Norway and mainland Europe. They are rare in the West Atlantic.

RELATION TO HUMANS

The blue whale was hunted almost to extinction up until the mid-1900s. The last recorded catches were off Spain in 1978. The species is now protected globally.

CONSERVATION AND MANAGEMENT

There are international management regimes through NAMMCO and the International Whaling Commission (IWC).

In the most recent regional assessment (2023) for Europe the species is listed as ‘Near threatened’ but increasing’ in the IUCN Red List. It is listed as ‘Vulnerable’ on the Norwegian, Greenlandic and Icelandic national red lists.

Scientific name: Balaenoptera musculus

Faroese: Royður

Greenlandic: Tunnulik

Icelandic: Steypireyður

Norwegian: Blåhval

Danish: Blåhval

English: Blue whale

At least three subspecies: B. musculus intermedia (found in Antarctic waters, the largest subspecies), B. musculus musculus (found only in the Northern Hemisphere), and B. musculus brevicauda (found in the subantarctic zone of the Southern Indian Ocean and Southwestern Pacific Ocean, known as the “pygmy blue whale”).

LIFESPAN

Blue whales live for at least 80–90 years, and probably longer than this.

AVERAGE SIZE

On average, blue whales weigh between 50 and 150 tonnes, and 24–28 m in length. They are larger in the Southern Hemisphere and females are slightly larger than males.

PRODUCTIVITY

From about 10 years of age, females have one calf every 2–3 years.

MIGRATION AND MOVEMENTS

This is not well documented, but there is some migration between high-latitude feeding grounds in summer and lower-latitude breeding grounds in winter.

FEEDING

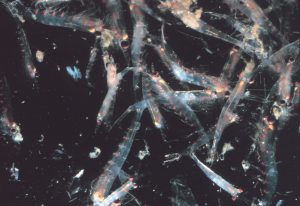

Blue whales lunge feed almost exclusively on euphausiids (krill).

General characteristics

The blue whale is the largest of the baleen whales and also the largest animal to have ever lived on Earth. Its blow is characteristically tall at 10–12 m high and is denser and broader than that of the fin whale.

They have a bluish grey mottled pigmentation with light and dark patches giving them a lighter appearance than most other large whales. These patches are unique to each individual and are therefore used as a basis for photo identification.

The flippers are long and bluntly pointed and can reach lengths up to 15% of total body length. The dorsal fin is proportionally smaller than in other whales of this family and it is located far back on the body. When the whale surfaces, the dorsal fin becomes visible well after the blow.

Blue whales are also more tapered and elongated than other rorqual whales and have a broad, U-shaped head. The shoulder and blow hole region are also raised more out of the water than other rorquals when surfacing. Less than 20% of blue whales in the North Atlantic raise their fluke when diving (Sears & Perrin 2018).

Blue whale baleen is black, with over 800 plates per individual, and 55–68 throat grooves extend from the throat to the navel.

In the Northern Hemisphere, the average weight of blue whales is 50–150 metric tonnes and their length 24–28 m, with females being slightly larger than males. The Antarctic blue whale is larger, reaching up to 32.6 m in length and weighing up to 190 tonnes.

Did you know?

The blue whale is the largest animal to have ever lived on Earth, surpassing even the largest known dinosaur – Argentinosaurus huinculensis. The blue whales found in the Northern Hemisphere, which are smaller than the Antarctic blue whale, can weigh as much as 25 African elephants. The tongue alone weighs around 2.7 metric tonnes, and the heart weighs approximately 180 kg.

Life history and ecology

Lifespan

Blue whale longevity is thought to be at least 80–90 years, probably longer. Photo identification studies have confirmed ages of more than 40 years (Sears and Perrin 2018, Øien 2019).

The age of the blue whale (like for other baleen whales) is read in the yearly deposit seen on the waxy ear plug. This is similar to the way we read the age of a tree from its annual growth rings. Blue whale ear plugs are larger than most other balaenopterid whale plugs.

Reproduction

Blue whale females reach sexual maturity when they are about 10 years of age, males when they are a couple of years older. Little is known about blue whale mating rituals, but rigorous surface displays of up to 50 minutes have been documented in the Gulf of St. Lawrence from summer into autumn, some taking place for as long as five weeks (Sears and Perrin 2018). Blue whales have also been observed racing each other, most likely as a form of male competition to impress females (Torres 2016).

The mating period is in autumn, and females give birth every 2-3 years in winter, after a 10-12 month gestation period. The calves are 2-3 tonnes and 6-7 m at birth. They drink up to 200 litres of milk a day, giving them a daily weight gain of more than 100 kg. Calves are weaned at approximately 16 m and 6-8 months of age.

A hybrid of fin and blue whale at the Icelandic whaling station © Marine Research Institute, Iceland

No specific breeding grounds have been discovered in any ocean, but mothers and calves are sighted regularly in the Gulf of California, Mexico in late winter and spring (Sears & Perrin 2018). There does not seem to be any area in the Northeast Atlantic where mothers have been observed with calves.

Hybridisation

Several hybrids of fin and blue whales (some pregnant) have been documented and some of these have been genetically confirmed (Árnason et al. 1991, Spilliaert et al. 1991, Bérubé & Aguilar 1998, Cipriano & Palumbi 1999, Berube et al. 2017). In 2013 and 2018, hybrids were caught west of Iceland, with the 2018 whale confirmed as the offspring of a fin whale father and blue whale mother (MRFI 2018, see also the section on Hunting and Utilisation).

Recent genetic research suggests that hybridisation may be more common than previously thought. All present-day North Atlantic blue whales tested showed signs of gene flow from another rorqual: about 3.5 percent of their genome comes from fin whales, and this gene flow appears to be one-way, from fin to blue whales (Jossey et al. 2024).

Feeding

The blue whale requires about 1.5 million kilocalories a day (Ellis 1991). It eats up to one metric tonne per feeding session and consumes 3.6 tonnes per day (NOAA n.d.). It appears to feed almost exclusively on euphausiids (krill) (Mizroch et al. 1984, Ellis 1991, Sears & Perrin 2018, Øien 2019). In the North Atlantic generally, the krill species Meganyctiphanes norvegica and Thysanoessa spp. are consumed (Visser et al. 2011, McQuinn et al. 2016). The specific feeding ecology of blue whales in Icelandic waters has not been well studied (Vikingsson et al. 2015).

When high concentrations of prey are encountered, blue whales feed by lunging and gulping large mouthfuls, expelling water through their baleen when closing the mouth (Sears & Perrin 2018). They feed mostly during daytime, both at the surface and at depths (usually below 100 m (Sears & Perrin 2018)). Blue whales feeding down to 300 m have been recorded off California, as well as progressively shallower feeding dives after dark, with a shift into non-feeding dives during the night (Calambokidis et al. 2008).

Did you know?

Blue whale hearts can beat as slow as two beats per minute! When a blue whale feeds at depth, its heart rate slows down to conserve oxygen, beating an average of four times per minute, with the lowest extreme recorded at two times per minute. It speeds up again as the whale approaches the surface, reaching a rate of 37 beats per minute while the whale breathes (Goldbogen et al. 2019).

Feeding strategies

Large whales exhibit different feeding strategies, with some whales lunging for food, while others “cruise along” with their mouths open, sifting out water as they go. The blue whale is a lunge-feeder, meaning that they “attack” patches of prey at speed while opening their mouths, resulting in an instant slowing of their speed.

Out of 6 identified rorqual surface lunge-feeding behaviours, blue whales were shown to exhibit 4 (Kot et al. 2014). This included left and right lateral lunges as well as ventral lunges clockwise and counter-clockwise. No blue whales showed oblique lunges (upright body orientation at oblique angles) or vertical lunges. There was evidence of behavioural lateralization (with a preference for right-sided lunges). Blue whales also exhibited less diversity in behaviours at depth, most likely due to the shorter time available to feed when using more energy-demanding behaviours at depth.

Underwater lunges have been documented by data tags and underwater cameras attached to the whales (Calambokidis et al. 2008, Goldbogen et al. 2012). These behaviours include lunges into dense aggregations of krill during characteristic series of vertical movement at depth and 360° rolling lunge-feeding manoeuvres to both position their lower jaws and visually process the prey field. You can see footage of this below.

Did you know?

Blue whales can consume up to 3,600 kg of food per day, constituting about 40 million individual krill.

Behaviour

The blue whale is seen most commonly alone, sometimes in pairs. A maximum group size of three was observed during the 2015 Icelandic and Faroese NASS survey, while 81% of the sightings were composed of single individuals (Pike et al. 2019). Concentrations of more than 50 can, however, be found spread out in areas of high productivity (Sears & Perrin 2018).

Diving/swimming

Generally, the blue whale stays under water for 8–15 minutes at a time (Øien 2019). However, diving times of up to 36 minutes have also been documented. Normal swimming speed when feeding has been recorded between 3–6 km/hr, and travel speed between 5–30 km/hr.

Blue whales have been shown to exhibit extended gliding sequences, which decrease the energetic cost of diving compared to active swimming (Williams et al. 2000). With increased dive depth, the whales displayed longer gliding sequences, exceeding 78% of the descent period for the deepest dives recorded. Stroke frequency on the initial dive was 6–10 per minute.

Deployments of Crittercam in the Southern California Bight revealed consistent feeding at depths of 250–300 m, deeper than had been previously reported for blue whales (Calambokidis et al. 2008).

Vocalization

Blue whales vocalize regularly throughout the year, with the highest level of activity from midsummer to winter. The majority of their song is of such a low frequency that it is undetectable to the human ear (Sears & Perrin 2018). Blue whales from most regions emit long, multi-part 15-40 Hz phrases, with phrase durations varying from 18–60 seconds and phrase periods around 70–120 seconds (Mellinger & Clark 2003). At 188 dB, blue whale sounds are also among the loudest sounds made by any animal, and they can be heard for hundreds, if not even thousands, of kilometres under optimal conditions (Sears & Perrin 2018).

Blue whale song can be divided into 10 types. The best-known sounds are from the Pacific Ocean where there are 4 different types, while there is only one song type in the North Atlantic (McDonald et al. 2006). A decline in the tonal frequency of blue whale song has also been found, with the best documented song type now at a frequency 31% lower than it was in the 1960s (McDonald et al. 2009).

A low-intensity, very low-frequency sound following a tonal FM downsweep (9 and 11 Hz) has been recorded in blue whales from both the North Atlantic and Northeastern Pacific (Mellinger & Clark 2003). There are distinct differences in sounds produced by blue whales between regions, and the sounds can thus be used to delineate the population structure of these widely dispersed and nomadic whales (Mellinger & Clark 2003, McDonald et al. 2006, Sears & Perrin 2018).

Listen to blue whale vocalisations from the links below:

Predators

Being so large, the blue whale has few natural enemies. The killer whale is the principal predator and is known to work in groups to attack blue whales. As much as 25% of photo-identified blue whales off Mexico in the North Pacific carry scars originating from killer whale teeth on their tails. There is, however, little evidence of these kinds of attacks in the North Atlantic or Southern Ocean (Sears and Perrin 2018). In spring 2019, killer whales were observed attacking and killing pygmy blue whales on two occasions off the coast of Australia.

Other natural sources of mortality

Ice entrapments

40 blue whales have been killed by ice entrapments in the Northwest Atlantic since 1974, with whales being crushed, stranded or suffocated (Gomez et al. 2017, Sears & Perrin 2018). In 2014, a total of 9 blue whales were killed after getting trapped in shifting ice in the Gulf of Maine, posing a significant loss to an already small population (“9 blue whales die after getting trapped off Newfoundland’s coast” 2014). There does not seem to be any record of ice entrapments of this scale in the Northeast Atlantic.

Distribution and habitat

Worldwide distribution

The blue whale is a cosmopolitan species found in all the major oceans of the world, with a tendency to remain in deep waters. The population structure is not clear, and both three and four large geographic regions have been suggested. The three regions currently accepted are the North Atlantic, North Pacific, and Southern Ocean, while it is still unclear whether the blue whales found in the Northern Indian Ocean constitute their own population (Sears & Perrin 2018).

Blue whale distribution is probably dictated by food availability and sea ice, and to a lesser extent, predation risks (Lesage et al. 2018, Sears & Perrin 2018). Sea surface temperature, regional concentrations of chlorophyll, and ocean depth provided the greatest contributions to a blue whale species distribution model built by Gomez et al. (2017).

Distribution in the North Atlantic

Historically

Historical whaling information indicates a distribution around Svalbard and the Northern Norwegian coast, Iceland, the Faroe Islands, Shetland, Ireland, the UK and Eastern Canada, (off Newfoundland and the Gulf of St. Lawrence) (Sigurjónsson & Gunnlaugsson 1990). Only a few blue whales were caught off Spain and Portugal, although the last recorded catches were six whales off Spain in 1978 (Allison 2017).

American whalers in the 18th and 19th century also reported encounters with blue whales across the southern half of the North Atlantic, in tropical and warm temperature latitudes during winter months. Summer encounters showed a narrower and more northerly distribution. However, these logbook entries only cover the extent of the whaling areas, and areas such as the Gulf of St. Lawrence and Iceland were seldom visited by American whalers (Reeves et al. 2004).

Today

The low abundance of blue whales and their deep water and offshore preferences have made them difficult to observe and study. They have only been studied intensely along the north shore of the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Their seasonal occurrence and movements elsewhere in the North Atlantic are poorly known (Reeves et al. 2004).

The available sightings and acoustic data show a wide-ranging use of the North Atlantic, with blue whales moving over great distances and being observed from north of Disko Bay and off Svalbard in the north, to south of Bermuda and off the Cape Verde Islands (e.g. Reeves et al. 2004, Sears et al. 2005, MICS n.d., NAMMCO 2017b). See also below under Migration.

Central and East Atlantic

The largest aggregation of blue whales in the North Atlantic is found around Iceland; otherwise, they are rare in the Northeast Atlantic. In recent years, blue whales have been sighted regularly around Svalbard and Jan Mayen. There have, however, been too few sightings to estimate abundance from the four series of Norwegian mosaic surveys done since 1996 (Pike et al. 2009, 2019; Øien 2009, 2019; Leonard and Øien 2020a,b).

Between 1987 and 2001, the increase in blue whale abundance was higher in the northeast than in the west of Iceland (Pike et al. 2009). This indicates a northward shift in relative distribution. This shift is consistent with the experience of whale watching companies in Iceland, as well as photo-identification studies showing that at least some of the whales previously found in the west had moved to the northeast (Vikingsson et al. 2015). During the Icelandic and Faroese shipboard surveys in 2015, blue whale sightings were concentrated in the north and west of Iceland, particularly off the eastern coast of Greenland (Pike et al. 2019).

West Atlantic

In the summer, blue whales are sighted in Disko Bay, and 2016 was the first year with consistent sightings all summer (NAMMCO 2017b).

Four important feeding and socializing areas have been identified off eastern Canada: the lower St. Lawrence Estuary and north-western Gulf of St. Lawrence, the shelf waters south and southwest of Newfoundland, the Mecatina Trough area, and the continental shelf edge of Nova Scotia (Lesage et al. 2018).

Did you know?

The blue whale’s scientific name is Balaenoptera musculus. Balaenoptera (the genus name), comes from Latin “balaena” (whale) and Ancient Greek “pteron” (fin). The specific name, musculus, is Latin for “muscle”, but it can also be interpreted as “little mouse”. It is highly likely that Carl Linnaeus, who first described the blue whale scientifically, was well aware of this double meaning of the name he gave it.

Migration

The blue whale undertakes extensive north-south migrations each year (Mizroch et al. 1984, Heide-Jørgensen et al. 2001, Sears et al. 2005, Pike et al. 2009, 2019). Blue whales are usually present in the northern areas of the North Atlantic only during the summer months (Pike et al. 2009). They appear to depart from northern areas earlier in autumn than fin or humpback whales (Pike et al. 2019).

Memory appears to play an important role in the movement decisions of blue whales, which tend to go to areas where they have experienced plenty of food over several seasons (Abrahms et al. 2019). Blue whales have been shown to forage while they migrate, which contradicts the common belief that these animals fast during this period (Silva et al. 2013).

Central and East Atlantic

Whales tagged off Svalbard and East Greenland have been tracked south to Iceland (Heide-Jørgensen et al. 2001, NAMMCO 2017b, 2018a), moving through the Denmark Strait.

The area southwest of Ireland might also be part of the migration route from high latitudes in summer to winter feeding areas in the Northwest African upwelling zones (Baines et al. 2017). Blue whales are sighted frequently in the Azores during spring and early summer and whales tagged here have been tracked almost up to Iceland (Silva et al. 2014, NAMMCO 2017b). One individual has also been identified both off Mauritania and Iceland (Sears et al. 2005).

West Atlantic

A seasonal shift in Baffin Bay–Davis Strait from a winter dominance of Arctic cetaceans to a summer dominance of temperate species like the blue whale has been observed since the 18th century. Blue whales were reported as moving into Greenlandic waters (up to 76ºN) in August-September and disappearing from Baffin Bay–Davis Strait by late November (Laidre & Heide-Jørgensen 2012).

Blue whales are known to frequent the Gulf of St. Lawrence during the summer and the eastern Scotian Shelf between January and November (e.g. Gomez et al. 2017). An extension of the summer feeding areas to autumn has been confirmed with evidence for new feeding areas off southern Newfoundland and Nova Scotia (Lesage et al. 2017). Two “transit corridors” were identified in eastern Canada: the Cabot and Honguedo Straits (Lesage et al. 2017). The wintering areas in the west Atlantic include the Gulf of St. Lawrence, southwest Newfoundland and the Scotian Shelf, as well as the Mid-Atlantic Bight off the US coast and warm, deep oceanic waters off this area.

North Atlantic stocks

Different timing of depletions of feeding stocks off Norway, Iceland, and the Western Atlantic suggest that discrete feeding aggregations exist, with limited mixing between areas (Pike et al. 2009). Photo-identification studies also suggest that there are at least two largely discrete blue whale populations in the North Atlantic (Sears et al. 2016).

Photo-identification studies have found no matches between whales photographed off the Azores, Spain or the Canary Islands and the rest of the North Atlantic (Sears et al. 2005). However, whales tagged off the Azores have been tracked almost up to Iceland (NAMMCO 2017). One individual has been identified both off Mauritania and Iceland (Sears et al. 2005). Despite the first St Lawrence (1984) to Azores (2014) match, comparison of the Northwest Atlantic and Northeast Atlantic blue whale catalogues revealed no further matches between the East and the West (Sears et al. 2016).

In the Northwest Atlantic, records are centred in eastern Canadian waters, ranging from west Greenland and south along North America to New England.

In the Northeast Atlantic, blue whale observations are centred in Icelandic waters. In summer they extend from Denmark Strait, Iceland, Jan Mayen, north to Spitsbergen and the Barents Sea, moving south to Northwest Africa in winter (e.g. Sears & Calambokidis 2002, Sears et al. 2005, 2015, Sears & Perrin 2018, MICS n.d.).

A new genetic study has shown that blue whales in the Northeast and Northwest Atlantic are not completely separate groups. Although there are some small differences between them, the study found that whales from the western side (for example, off Canada) are regularly mixing with those from the eastern side (around Iceland and Norway). In fact, more whales are moving from west to east than the other way around. This indicates that all blue whales in the North Atlantic are likely part of one large, connected population, even if there are some regional differences (Jossey et al. 2024).

Current abundance and trends

Globally

A recent reliable global population estimate is not available. However, it is thought that mature blue whales number between 5,000 and 15,000 individuals globally, and between 10,000 and 25,000 in total (Cooke 2018). This is markedly different from the estimate that there were 140,000 in 1926. Since its protection in 1966, the population is now increasing in the North Atlantic and the Antarctic.

Northeast Atlantic

Central North Atlantic

The main aggregation of blue whales in the North Atlantic is found off Western and Northern Iceland, where the population seems to be increasing (Pike et al. 2009, 2019). The latest abundance estimate for this region is from 2015 and estimates the presence of 2,490 animals (95% CI: 1,234 – 5,022) (NAMMCO 2019).

The previous estimate is from 2001. No abundance estimate was made during the 2007 surveys of the area due to too few sightings. During the Icelandic and Faroese shipboard surveys in 2015, blue whale sightings were concentrated to the north and west of the survey area, particularly off the eastern coast of Greenland, and uncommonly in the eastern half of the area (Pike et al. 2019).

For the period 1987-2001, the rate of increase of blue whales off Iceland and the Faroe Islands was 9% annually (Pike et al. 2009). The uncorrected estimate from the 2015 survey is more than double that of the two previous ones, suggesting an increase in blue whale numbers in the entire area, and particularly to the west of Iceland (Pike et al. 2019).

| Year | Estimate | 95% CI | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1987 | 222 | 115-400 | Uncorrected estimate. |

| 1989 | 531 | 288-759 | Uncorrected estimate. |

| 1995 | 979 | 137-2,542 | Best estimate of NASS 1987-2001. Uncorrected estimate. |

| 2001 | 855 | 358-1,419 | Negatively biased because the main blue whale concentration was most likely missed during the survey. Uncorrected estimate. |

| 2015 | 3,000 | 1,377-6,534 | Estimate corrected for perception bias. |

Eastern North Atlantic

The blue whale continues to be rare in the rest of the Northeast Atlantic, particularly around Svalbard and along the coast of Northern Norway (Pike et al. 2009). There have been too few sightings to estimate abundance from the four series of Norwegian mosaic surveys since 1996 (Øien 2009, Leonard & Øien 2020a,b). However, there were notable increases in the numbers of blue whales observed in Svalbard between 2011 and 2015. 24 whales were sighted close to Svalbard and between Svalbard and Franz Joseph Land during the Norwegian Sightings survey and the Arctic part of the ecosystem survey in 2014 (NAMMCO 2014, 2015). During a survey in August 2017, blue whales were also seen north of Svalbard. There was only one blue whale sighting in the East Greenland 2015 survey (Hansen et al. 2019).

Sufficient data for abundance estimates of blue whales was not obtained during the SCANS-III survey in European Atlantic waters in the summer of 2016 (Hammond et al. 2017). However, 16 blue whales were sighted during a survey over the Porcupine Seabight, southwest of Ireland in July to October 2013. This exceeded the total number of blue whales previously reported from Irish waters (Baines et al. 2017).

Stock status

No assessment has been performed yet for the blue whale in the North Atlantic, in part because of a lack of reliable abundance estimates for the whole area.

Blue whales are protected over their whole range. Although the Northeast Atlantic population seems to be increasing (Pike et al. 2009, 2019, Cooke 2018), the situation for the Northwest population is less clear.

The Greenlandic Red List (2007) lists the species as data deficient.

The Icelandic (2018) and Norwegian (2015) Red Lists both list the species as vulnerable.

STATUS ACCORDING TO OTHER INTERNATIONAL ORGANISATIONS

The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) listed the blue whale as Endangered following an assessment in 2002 (COSEWIC 2002). This was re-examined and confirmed again in 2012 (COSEWIC 2012) and the species is also listed as endangered by the Canadian Species at Risk Act (SARA).

The International Whaling Commission (IWC) has not carried out a full assessment of the present status, but notes “Encouragingly though, the available evidence suggests they are increasing, at least in the area of the central North Atlantic”.

At a global level, the IUCN Red List classifies the species as Endangered, but increasing in those regions where the species was most depleted (the Antarctic and the North Atlantic) (Cooke 2018).

The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) has the species in its Appendix I. This appendix lists species that are the most endangered among CITES-listed animals and plants. This includes species threatened with extinction, for which CITES prohibits international trade in specimens except when the purpose of the import is non-commercial.

The Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS) lists the blue whale in its Appendix I. This is comprised of migratory species that have been assessed as being in danger of extinction throughout all or a significant portion of their range. “Parties that are a Range State to a migratory species listed in Appendix I shall endeavour to strictly protect them by: prohibiting the taking of such species, with very restricted scope for exceptions; conserving and where appropriate restoring their habitats; preventing, removing or mitigating obstacles to their migration and controlling other factors that might endanger them.”

Management

Blue whales fall under the management of both the International Whaling Commission, and since its inception in 1992, NAMMCO. NAMMCO provides management advice to the Faroe Islands, Greenland, Iceland, and Norway on the conservation status of blue whales.

Blue whales have been protected worldwide since 1966 (Cooke 2018). This was following severe depletion rates of blue whale populations during the first half of the 20th century – when they were estimated to be at 89-97% of the 1926 population.

The IWC adopted a moratorium on whaling in 1982, which sought a pause to all commercial whaling from the 1985/1986 season until adequate assessment and regulatory measures could be put in place (Ellis 1991).

MANAGEMENT MEASURES IN NAMMCO MEMBER COUNTRIES

Blue whales are protected by all NAMMCO member countries, which were actually the first countries to initiate protection for this species.

Iceland

A temporary complete ban on whaling around Iceland for whales larger than common minke whales was declared in 1916, although whaling was resumed in 1948. Hunting of blue whales was completely prohibited in Iceland in 1959 (Pike et al. 2009), 7 years before international protection came into effect.

Norway

Whaling in Norway, including for blue whales, was temporarily banned for a short period from 1905 (Tønnessen & Johnsen 1982).

In 1929, the Norwegian Whaling Act was drafted. It forbid the capture of right whales, females and calves of all species, and blue whales less than 18 m long. This led to the first International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling in 1946. This convention protected right whales and females with calves, as well as California grey whales. The Convention also established the International Whaling Commission.

Hunting and utilisation

Historically

The blue whale was too swift and powerful for the 19th century whalers to hunt. Blue whales were thus not hunted on a regular basis until equipment developed to a point that could allow it. In particular this included the arrival of deck-mounted harpoon cannons. This type of blue whaling began in the North Atlantic in 1868, eventually spreading to other oceans when the Northeast Atlantic population had been severely depleted (Cooke 2018). The greatest numbers were caught between the early 1900s to the late 1930s (Sears & Perrin 2018). By the time worldwide protection came into effect in 1966, the populations in both the North Atlantic and the Antarctic were estimated to be depleted into the low hundreds (Cooke 2018).

According to hunting logbooks, about 11,000 blue whales were killed in the North Atlantic (Sigurjónsson & Gunnlaugsson 1990, Sears & Perrin 2018). However, the total number was probably between 15,000 and 20,000, taking into consideration the substantial struck and lost rate pre-1916 as well as the unspecified large whales reported (Cooke 2018). The largest catches were taken off Iceland, Northern Norway and Svalbard.

Whaling efforts decreased in the North Atlantic as stocks were depleted and whalers moved to the Southern Ocean. Following the 1966 implementation of worldwide protection, the blue whale hunt ceased. However, Spain was not a member of the IWC until 1979, and 15 blue whales were caught in Iberian waters between 1966 and 1978 (Covelo et al. 2017). Blue whales were also caught illegally by USSR fleets until 1972 (Cooke 2018).

Today

Blue whales have been protected worldwide since 1966, and no deliberate catch of blue whales has been recorded since 1978 (Cooke 2018).

In July 2018, there was a “worldwide uproar” when a whale caught by Icelandic hunters was speculated to be a blue whale. However, preliminary assessments and thorough genetic testing proved that the whale was a blue-fin whale hybrid (MFRI 2018). The hybrid was taken off the Icelandic quota for fin whales, which was 161 in 2018.

Recent research by Pampoulie et al. (2020) has indicated that all but one of the fin/blue whale hybrids that have been identified in Icelandic waters were the result of successful mating between a male fin whale and a female blue whale. They also suggested that at least one of these animals was a second generation adult resulting from a backcross between a female hybrid and a male fin whale. Furthermore, hybridisation between blue and fin whales may be underestimated and could be an additional factor challenging blue whale population recovery (Pampoulie et al. 2020).

Other human impacts

The main threat to the blue whale historically has been overexploitation. However the species has been globally protected since 1966. The current anthropogenic activities that affect blue whales are habitat degradation and oceanographic changes.

HABITAT DEGRADATION

A range of anthropogenic activities has the potential to degrade habitats important to blue whale survival. These can occur both when whales are present and absent. These activities include:

- entanglement (e.g. in marine debris, fishing gear, etc)

- physical injury and death from vessel collisions (e.g. in shipping lanes)

- acoustic pollution with disturbance from low-frequency noise (e.g. from vessels, seismic surveys, military activities)

- changing water quality and pollution (e.g. from runoff from agriculture, oil spills)

- prey depletion due to over-hunting

- human harassment through whale watching programmes

The biggest threats for blue whales are listed as ship strikes, disturbance from increasing whale watching activity and noise (e.g. shipping and seismic surveys) (e.g. COSEWIC 2002, 2012, Cooke 2018). Priority monitoring areas for blue whales in the Northwest Atlantic have been identified and these areas overlap with known shipping routes and sites for seismic surveys (Gomez et al. 2017).

Entanglements

Incidental catches of blue whales in fisheries appear to be rare and entanglements of blue whales have not been reported in NAMMCO member countries.

However, there are reports from other areas. 12% of whales observed in the Northwest Atlantic carry marks related to contact with fishing gear. However, few lethal entanglements have been reported (Sears & Perrin 2018). Identifying the source of scars is harder for blue whales from cold waters, as they often carry scars attributable to contact with ice (Cooke 2018). In US waters, the first confirmed entangled blue whale was in 2015, and new entanglements were reported both in 2016 and 2017 (NOAA 2018). An entangled blue whale was reported in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence in 2002.

Ship strikes

The blue whale has been identified as one of the 11 species of great whales found to collide with ships, although there are comparatively fewer records for blue whales than for instance fin or humpback whales. This could, however, be due to the comparatively fewer numbers of blue whales (Laist et al. 2001). Ship strikes fatal to whales first occurred late in the 1800s but remained infrequent until about 1950, when the number and speed of vessels increased. The most lethal or severe injuries are caused by ships 80 m or longer, or with ships travelling 14 km or faster.

Blue whales (as other whales in the fin whale family), exhibit negative buoyancy, thereby reducing energetic costs when diving (Goldbogen, Friedlaender et al. 2013, Williams et al. 2000). This negative buoyancy also means that these animals sink when dead, challenging recovery and identification. Ship strikes could actually go unnoticed, especially by large vessels, as visibility immediately in front of the ships is more limited and the greater mass makes impact less likely to be felt. There have even been instances of dead whales being carried on bows of ships and not being detected until the vessel reached port (Laist et al. 2001, Rockwood et al. 2017).

Blue whale ship strikes in the North Atlantic

There are not many records of blue whale ship strikes in the Atlantic Ocean. Although reporting may not be comprehensive, there are no reports of ship strikes from any NAMMCO member countries and none have been reported in the IWC’s ship strike database. Laist et al. (2001) found only one record of a ship strike from the Atlantic Ocean in their review; a dead, juvenile blue whale that was carried on the bow of a tanker as it entered Narragansett Bay, Rhode Island in 1998. However, at least 25% of photo-identified whales in the Gulf of St. Lawrence carry scars attributable to collisions with ships, something that could have a negative impact on populations (Laist et al. 2001, Rockwood et al. 2017, Sears & Perrin 2018).

Noise

Increasing anthropogenic noise from shipping and oil explorations may limit the recovery of blue whales (Sears & Perrin 2018). This is because noise disturbance can lead to changes in behaviour and a cessation of feeding. Blue whales have been shown to alter their vocalizations in areas with ongoing seismic surveys, calling consistently more on seismic exploration days than non-exploration days (Di Iorio & Clark 2010).

Military sonar

Several aspects of blue whale diving behaviour have been shown to be significantly affected by the exposure to mid-frequency sound, with the whale’s initial behaviour state strongly affecting reactions. Whales that were deep feeding or not feeding were affected the most, while animals feeding at the surface were affected the least (Goldbogen, Southall et al. 2013). Similarly, responses to military sonar were found in more than 50% of deep-feeding whales, while surface-feeding whales displayed no changes (Southall et al. 2019). Both studies found behavioural changes that included termination of feeding behaviours, changes in diving behaviour and horizontal avoidance of the sound source. The cessation of feeding, especially, could significantly affect individual blue whales, as it reduces foraging efficiency and could also affect the whales on a population level.

Persistent organic pollutants

The level of presence of persistent organic pollutants in blue whales is not known. As with other marine mammal species, it may have an impact on reproduction and limit the recovery of certain populations (Sears & Perrin 2018).

OCEANOGRAPHIC CHANGES

Climate change

The exact implications of climate change on oceanographic conditions and processes are unclear, as well as their subsequent implications for whales. Reduced productivity of some ecosystems, altered ocean water temperatures, changing ocean currents, rising sea levels and reductions in sea ice are, however, predicted and widely recognised as likely consequences of climate change. All of these have the potential to impact whale populations.

Due to both increasing ocean acidity and reduced ocean productivity associated with warming waters, a decline in the Antarctic blue whale’s main food, the krill species Euphausia superba and E. crystallorophias is predicted (Cooke 2018). Such changes are also likely in other oceans.

Research in NAMMCO member countries

The blue whale is not a target species of abundance surveys in the North Atlantic. However, it is still encountered and recorded during surveys in all NAMMCO areas.

Greenland

There is no ongoing research on blue whales in Greenland, but they are recorded on acoustic buoys.

Iceland

“Project Blue Whale” launched in 2008 and aims to gain more knowledge of blue whales using techniques such as photo-identification, behavioural and prey logging, sound recording, genetic sampling, and tagging with AUSOMS mini (Automatic Underwater Sound Monitoring System). This ongoing project is led by researchers from the University of Iceland’s Research Centre in Húsavik (HRC) and involves collaboration with the Marine and Freshwater Research Institute and the Húsavik Whale Museum. The photo-identification part of this project was started in 2001, and is mostly focusing on blue and humpback whales and white-sided dolphins, the species most commonly observed in Skjálfandi Bay.

One blue whale was satellite tagged north of Iceland in July 2013 and two in 2014. The whale tagged in 2013 travelled southwards to 59° N while the two tagged in 2014 travelled north of Iceland towards 73° N. In 2016, another blue whale was instrumented with a satellite tag and data was received from 24th June until 2nd August (National Progress Report Iceland 2016).

Animals identified earlier via photo-id off West Iceland in mid-summer have been found north of Iceland in mid-summer in recent years. Iceland is also collecting biopsy samples, with 10-20 samples stored in the MRI archive in 2014 (NAMMCO 2014). In 2015, the HRC made recordings of blue whales using a large hydrophone array (National Progress Report Iceland 2015). From 2017 to 2019, acoustic tags were deployed on a total of 6 blue whales in Skjálfandi Bay (National Progress Report Iceland 2017, 2018, 2019).

For a project funded by WWF, and in collaboration with Whale Wise, two sound traps were deployed off west-Iceland in 2020 to collect blue whale and shipping traffic data. Additionally, a soundtrap was deployed for 3 months in Skjálfandi Bay to investigate the sound scape of the bay (National Progress Report Iceland 2020).

Norway

Although not a target species of surveys, the blue whale is regularly sighted and recorded around Svalbard and Jan Mayen (Øien 2019). During a survey in August 2017, many blue whales were seen north of Svalbard. A total of 4 summer surveys have been done, and Norway is preparing an analysis of the presence of blue whales in relation to relevant prey species in the upper 100-150 m (NAMMCO 2017).

Passive acoustic listening devices have been deployed at various sites around Svalbard, collecting data on the phenology of arrivals and departures to the area (NAMMCO 2015). These devices were serviced and redeployed in 2019 (National Progress Report Norway 2019).

Photos for identification studies are also collected, with Iceland providing photos to the same study (NAMMCO 2016, 2017).

Satellite tracking

The Norwegian Polar Institute (NPI) started instrumenting animals with satellite tracking devices in 2014. They are also collecting biopsies for studies of genetics, diet and ecotoxicology. This work is ongoing, with new efforts scheduled for autumn 2019. In 2017, a total of 20 biopsies had been collected around Svalbard, with 4 more collected in 2018 and 1 in 2019 (NAMMCO 2017, National Progress Report Norway 2018, National Progress Report Norway 2019).

Initial results from the satellite tracks of tagged whales have showed that blue whales move in the same pattern between Svalbard and Iceland through the Denmark Strait, which was the same area where the sightings of blue whales occured during the surveys. One animal tagged in 2018 was close to the west coast of Iceland in November the same year. Two blue whales were tagged north of Svalbard with experimental MINTAG tags in 2024, showing similar movement towards the Denmark Strait.

Tagging and biopsy sampling of a blue whale by the NPI, in Isfjorden, Svalbard. © Andrew Lowther/Norwegian Polar Institute

Collaborative studies

Mingan Island Cetacean Study (MICS) curate the western and eastern North Atlantic blue whale catalogues. Blue whale photos collected around Svalbard and Iceland are contributed to these catalogues.

A worldwide project, “Happy whale”, helps track individual whales throughout the world’s oceans by providing a website were photos can be posted and become available for anyone to analyse and use (NAMMCO 2017).

In 2018, the Scientific Committee of NAMMCO was informed that the International Whaling Commission has recommended that an estimate of blue whales be generated, with a specific recommendation to use photo ID catalogues. The IWC has specifically requested participation in this work from Iceland, the US and Canada.

9 blue whales die after getting trapped off Newfoundland’s coast (2014, April 9), CTV News. Available at https://aus.libguides.com/apa/apa-newspaper-web

Abrahms, B., Hazen, E.L., Aikens, E.O., Savoca, M.S., Goldbogen, J.A., Bograd, S.J., Jacox, M.G., Irvine, L.M., Palacios, D.M. and Mate, B.R. (2019). Memory and resource tracking drive blue whale migrations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 116(12), 5582–5587. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1819031116

Allison C. (2017). International Whaling Commission Catch Data Base v. 6.1.

Árnason, Ú, Spilliaert, R., Pálsdóttir, Á.K. and Árnason, A. (1991). Molecular identification of hybrids between the two largest whale species, the blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus) and the fin whale (B. physalus). Hereditas, 115(2), 183–189. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1601-5223.1991.tb03554.x

Baines, M., Reichelt, M. and Griffin, D. (2017). An autumn aggregation of fin (Balaenoptera physalus) and blue whales (B. musculus) in the Porcupine Seabight, southwest of Ireland. Deep-Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 141, 168–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr2.2017.03.007

Beauchamp, J., Bouchard, H., de Margerie, P., Otis, N. and Savaria, J.-Y. (2009). Recovery Strategy for the blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus), Northwest Atlantic population, in Canada [FINAL]. Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series. Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Ottawa. 62 pp. Available at https://www.sararegistry.gc.ca/virtual_sara/files/plans/rs_blue_whale_nw_atlantic_pop_0210_e.pdf

Bérubé, M. and Aguilar, A. (1998). A new hybrid between a blue whale, (Balaenoptera musculus), and a fin whale, (B. physalus): Frequency and implications of hybridization. Marine Mammal Science, 14(1), 82–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-7692.1998.tb00692.x

Bérubé, M., Oosting, T., Aguilar, A., Hao, W., Kovacs, K. M., Landry, S., Larsen, F., Lydersen, C., Øien, N., Prieto, R., Ramp, C., Robbins, J., Sears, R., e Silva, M. A., Vikingsson, G. A. and Palsboll, P. (2017). Are the “Bastards” Coming Back? Molecular Identification of the First Live Blue and Fin Whale Hybrids in the North Atlantic Ocean. Abstract from 22nd Biennial Conference on the Biology of Marine Mammals, Halifax, Canada. Available at http://hdl.handle.net/11370/02e3db53-d0a9-42e7-9533-3725ecd1c016

Calambokidis, J., Schorr, G.S., Steiger, G.H., Francis, J., Bakhtiari, M. Marshall, G., Oleson, E., Gendron, D. and Robertson, K. (2008). Insights into the underwater diving, feeding, and calling behavior of blue whales from a suction-cup attached video-imaging tag (CRITTERCAM). Marine Technology Society Journal, 41(4), 19–29. https://doi.org/10.4031/002533207787441980

Cipriano, F. and Palumbi, S.R. (1999). Genetic tracking of a protected whale. Nature, 397, 307–308. https://doi.org/10.1038/16823

Cooke, J.G. (2018). Balaenoptera musculus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018: e.T2477A50226195. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T2477A50226195.en.

COSEWIC. (2002). COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Blue Whale Balaenoptera musculus in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 32 pp. Available at https://www.registrelep-sararegistry.gc.ca/default.asp?lang=En&n=D9FFF798-1

COSEWIC. (2012). COSEWIC status appraisal summary on the Blue Whale Balaenoptera musculus, Atlantic population, in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. xii pp. Available at https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/species-risk-public-registry/cosewic-assessments-status-reports/blue-whale-atlantic-appraisal-summary-2012.html

Covelo, P., Ocio, G. and Hidalgo, J. (2017). First record of a live blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus) in the Iberian Peninsula after three decades. Galemys, 29, 34–37. https://doi.org/10.7325/Galemys.2017.N6

Di Iorio, L. and Clark, C.W. (2009). Exposure to seismic survey alters blue whale acoustic communication. Biology Letters, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2009.0651

Ellis, R. (1991). Men and Whales. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

Goldbogen, J.A., Calambokidis, J., Friedlaender, A.S., Francis, J., DeRuiter, S.L., Stimpert, A.K., Falcone, E. and Southall, B.L. (2012). Underwater acrobatics by the world’s largest predator: 360° rolling manoeuvres by lunge-feeding blue whales. Biology Letters, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2012.0986

Goldbogen, J.A, Friedlaender, A.S., Calambokidis, J., McKenna, M.F., Simon, M. and Nowacek, D.P. (2013). Integrative Approaches to the Study of Baleen Whale Diving Behavior, Feeding Performance, and Foraging Ecology. Bioscience, 63(2), 90–100. https://doi.org/10.1525/bio.2013.63.2.5

Goldbogen, J.A., Southall, B.L., DeRuiter, S.L., Calambokidis, J., Friedlaender, A.S., Hazen, E.L., Falcone, E.A., Schorr, G.S., Douglas, A., Moretti, D.J., Kyburg, C., McKenna, M.F. and Tyack, P.L. (2013). Blue whales respond to simulated mid-frequency military sonar. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 280(1765). http://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2013.0657

Goldbogen, J.A., Cade, D. E., Calambokidis, J., Czapanskiy, M. F., Fahlbusch, J., Friedlaender, A. S., Gough, W. T., Kahane-Rapport, S. R., Savoca, M. S., Ponganis, K. V., & Ponganis, P. J. (2019). Extreme bradycardia and tachycardia in the world’s largest animal. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America,116(50) 25329-25332, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1914273116.

Gomez, C., Lawson, J., Kouwenberg, A.-L., Moors-Murphy, H., Buren, A., Fuentes-Yaco, C., Marotte, E., Wiersma, Y.F. and Wimmer, T. (2017). Predicted distribution of whales at risk: identifying priority areas to enhance cetacean monitoring in the Northwest Atlantic Ocean. Endangered Species Research, 32, 437–458. https://doi.org/10.3354/esr00823

Hammond, P.S., Lacey, C., Gilles, A., Viquerat, S., Börjesson, P., Herr, H., Macleod, K., Ridoux, V., Santos, M.B., Scheidat, M., Teilmann, J., Vingada, J. and Øien, N. (2017). Estimates of cetacean abundance in European Atlantic waters in summer 2016 from the SCANS-III aerial and shipboard survesy. Wageningen Marine Research. Available at https://synergy.st-andrews.ac.uk/scans3/files/2017/05/SCANS-III-design-based-estimates-2017-05-12-final-revised.pdf

Heide-Jørgensen, M.P., Kleivane, L., Øien, N., Laidre, K. L. and Jensen, M. V. (2001). A new technique for satellite tagging baleen whales: tracking a blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus) in the North Atlantic. Marine Mammal Science, 17(4), 949–954. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-7692.2001.tb01309.x

Jossey, S., Haddrath, O., Loureiro, L., Weir, J. T., Lim, B. K., Miller, J., Scherer, S. W., Goksøyr, A., Lille-Langøy, R., Kovacs, K. M., Lydersen, C., Routti, H., & Engstrom, M. D. (2024). Population structure and history of North Atlantic Blue whales (Balaenoptera musculus musculus) inferred from whole genome sequence analysis. Conservation Genetics, 25(2), 357–371. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10592-023-01584-5

Kot, B.W., Sears, R., Zbinden, D., Borda, E. and Gordon, M.S. (2014). Rorqual whale (Balaenopteridae) surface lunge-feeding behaviors: Standardized classification, repertoire diversity, and evolutionary analyses. Marine Mammal Science ,30(4), 1335–1357. https://doi.org/10.1111/mms.12115

Laidre, K.L. and Heide-Jørgensen, M.P. (2012). Spring partitioning of Disko Bay, West Greenland, by Arctic and Subarctic baleen whales. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 69(7), 1226–1233. https://doi.org/10.1093/icesjms/fss095

Laist, D.W., Knowlton, A.R., Mead, J.G., Collet, A.S. and Podesta, M. (2001). Collisions between ships and whales. Marine Mammal Science, 17(1), 35–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-7692.2001.tb00980.x

Lawson, J.W. and Gosselin, J.-F. (2009). Distribution and preliminary abundance estimates for cetaceans seen during Canada’s marine megafauna survey – A component of the 2007 TNASS. DFO Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat. Res. Doc. 2009/031. vi + 28 p. Available at https://files.pca-cpa.org/pcadocs/bi-c/2.%20Canada/3.%20Exhibits/R-0830.PDF

Leonard, D. and Øien, N. (2020a). Estimated Abundances of Cetacean Species in the Northeast Atlantic from Two Multiyear Surveys Conducted by Norwegian Vessels between 2002–2013. NAMMCO Scientific Publications, 11. https://doi.org/10.7557/3.4695

Leonard, D. and Øien, N. (2020b). Estimated Abundances of Cetacean Species in the Northeast Atlantic from Norwegian Shipboard Surveys Conducted in 2014–2018. NAMMCO Scientific Publications, 11. https://doi.org/10.7557/3.4694

Lesage, V., Gavrilchuk, K., Andrews, R.D. and Sears, R. (2017). Foraging areas, migratory movements and winter destinations of blue whales from the western North Atlantic. Endangered Species Research, 34, 27–43. https://doi.org/10.3354/esr00838

Lesage, V., Gosselin, J.-F., Lawson, J.W., McQuinn, I., Moors-Murphy, H., Plourde, S., Sears, R. and Simard, Y. (2018). Habitats important to blue whales (Balaenoptera musculus) in the western North Atlantic. DFO Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat. Res. Doc. 2016/080. iv + 50 p. https://waves-vagues.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/Library/40681373.pdf

Long, J. A. (2012). The Dawn of the Deed: The Prehistoric Origins of Sex. University of Chicago Press. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226002118.001.0001

Marine and Freshwater Research Institute (MFRI) (2018, July 19). Press release from the Marine and Freshwater Research Institute (MFRI) – Peculiar baleen whale – genetic results. Available at https://www.hafogvatn.is/

McDonald, M. A., Mesnick, S.L. and Hildebrand, J.A. (2006). Biogeographic characterization of blue whale song worldwide: Using song to identify populations. Journal of Cetacean Research and Management, 8(1), 55–65. Available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228639435

McDonald, M. A., Hildebrand, J.A. and Mesnick, S.L. (2009). Worldwide decline in tonal frequencies of blue whale songs. Endangered Species Research, 9, 13–21. https://doi.org/10.3354/esr00217

McQuinn, I.H., Gosselin, J.-F., Bourassa, M.-N., Mosnier, A., St-Pierre, J.-F., Plourde, S., Lesage, V. and Raymond, A. (2016). The spatial association of blue whales (Balaenoptera musculus) with krill patches (Thysanoessa spp. and Meganyctiphanes norvegica) in the estuary and northwestern Gulf of St. Lawrence. DFO Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat, Res. Doc. 2016/104. iv + 19 pp. Available at http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/csas-sccs/publications/resdocs-docrech/2014/2014_104-eng.html

Mellinger, D.K. and Clark, C.W. (2003). Blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus) sounds from the North Atlantic. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 114(2), 1108–1119. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.1593066

Mingan Island Cetacean Study (MICS). (n.d.). Blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus). Available at https://www.rorqual.com/english/our-whales/blue-whale

Mizroch, S.A., Rice, D.W. and Breiwick, J.M. (1984). The Blue Whale, Balaenoptera musculus. Marine Fisheries Review, 46(4), 15–19. Available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242159289

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). (n.d.). Blue Whales. Available at https://www.afsc.noaa.gov/nmml/education/cetaceans/blue.php

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). (2018). National Report on Large Whale Entanglements Confirmed in the United States in 2017. Available at https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/resource/document/national-report-large-whale-entanglements-2017

North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO). (2014). Report of the 21st Scientific Committee Meeting, 3-6 November, Norway. Available at https://nammco.no/topics/scientific-committee-reports/#2014

North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO). (2015). Report of the 22nd Scientific Committee Meeting, 9-12 November, Faroe Islands. Available at https://nammco.no/topics/scientific-committee-reports/#2015

North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO). (2016). Report of the 23rd Scientific Committee Meeting, 4-7 November, Greenland. Available at https://nammco.no/topics/scientific-committee-reports/#2016

North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO). (2017a). Marine Mammals: A multifaceted Resource. Available at https://nammco.no/topics/other_documents/#MMFR

North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO). (2017b). Report of the 24th Scientific Committee Meeting, 14-17 November, Iceland. Available at https://nammco.no/topics/scientific-committee-reports/#2017

North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO). (2018a). Report of the 25th Scientific Committee Meeting, 13-16 November, Norway. Available at https://nammco.no/topics/scientific-committee-reports/#2018

North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO). (2018b). Report of the Working Group on Abundance Estimates, 22-24 May, Denmark. Available at https://nammco.no/abundance_estimates_reports/

North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO). (2019). Report of Abundance Estimates Working Group, October 2019, Tromsø, Norway. https://nammco.no/abundance_estimates_reports/

Pike, D.G., Vikingsson, G.A., Gunnlaugsson, Th. and Øien, N. (2009). A note on the distribution and abundance of blue whales (Balaenoptera musculus) in the Central and Northeast North Atlantic. NAMMCO Scientific Publications, 7, 19–29. https://doi.org/10.7557/3.2703

Pike, D.G., Gunnlaugsson, T., Mikkelsen, B., Halldórsson, S.D. and Víkingsson, G.A. (2019) Estimates of the abundance of cetaceans in the central North Atlantic based on the NASS Icelandic and Faroese shipboard surveys conducted in 2015. NAMMCO Scientific Publications, 11. https://doi.org/10.7557/3.4941

Pampoulie, C.,Gíslason, D., Ólafsdóttir, G., Chosson, V., Halldórsson, S.D., Mariani, S. Elvarsson, B.Þ. et al. (2020). ‘Evidence of Unidirectional Hybridization and Second‐generation Adult Hybrid between the Two Largest Animals on Earth, the Fin and Blue Whales’. Evolutionary Applications https://doi.org/10.1111/eva.13091.

Ramp, C., Bérube, M., Hagen, W. and Sears, R. (2006). Survival of adult blue whales Balaenoptera musculus in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, Canada. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 319, 287–295. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps319287

Reeves, R.R., Smith, T.D., Josephson, E.A., Clapham, P.J. and Woolmer, G. (2004). Historical observations of humpback and blue whales in the North Atlantic Ocean: Clues to migratory routes and possibly additional feeding grounds. Marine Mammal Science, 20(4), 774–786. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-7692.2004.tb01192.x

Rockwood, R.C., Calambokidis, J. and Jahncke, J. (2017). High mortality of blue, humpback and fin whales from modeling of vessel collisions on the U.S. West Coast suggests population impacts and insufficient protection. PLoS ONE, 13(7): e0201080. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0183052

Sears, R. and Calambokidis, J. (2002). Update COSEWIC status report on the Blue Whale Balaenoptera musculus in Canada, in COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Blue Whale Balaenoptera musculus in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1–32 pp. https://www.registrelep-sararegistry.gc.ca/default.asp?lang=En&n=D9FFF798-1

Sears, R., Burton, C.L.K. and Vikingsson, G. (2005). Review of blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus) photo-identification distribution data in the North Atlantic, including the first long-range match between Iceland and Mauritania. Poster presented at the Sixteenth Biennial Conference on the Biology of Marine Mammals, San Diego, California. Available at https://www.rorqual.com/

Sears, R. and Perrin, W.F. (2018). Blue whale. In Würsig, B., Thewissen, J.G.M. and Kovacs, K.M. (eds.), Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals, 3rd ed., 110–114. London (UK): Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-804327-1.00070-4

Sears, R., Ramp, C., Santos, R., Silva, M.A., Steiner, L. and Vikingsson, G.A. (2016). Comparison of the Northwest Atlantic-NWA and Northeast Atlantic-NEA Blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus) photo-identification catalogs. Available at https://www.rorqual.com

Silva, M.A., Prieto, R., Jonsen, I., Baumgartner, M.F. and Santos, R.S. (2013). North Atlantic Blue and Fin Whales Suspend Their Spring Migration to Forage in Middle Latitudes: Building up Energy Reserves for the Journey? PLoS ONE, 8(10), e76507. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0076507

Silva, M.A., Prieto, R., Cascão, I., Seabra, M.I., Machete, M., Baumgartner, M.F. and Santos, R.S. (2014). Spatial and temporal distribution of cetaceans in the mid-Atlantic waters around the Azores. Marine Biology Research, 10, 123–137. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17451000.2013.793814

Southall, B.L., DeRuiter, S.L., Friedlander, A., Stimpert, A.K., Goldbogen, J.A., Hazen, E., Casey, C., Fregosi, S., Cade, D.E., Allen, A.N., Harris, C.M., Schorr, G., Moretti, D., Guan, S. and Calambokidis, J. (2019). Behavioral responses of individual blue whales (Balaenoptera musculus) to mid-frequency military sonar. Journal of Experimental Biology, 222. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.190637

Spilliaert, R., Vikingsson, G., Arnason, U., Sigurjonson, A. and Arnason, A. (1991). Species hybridization between a female blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus) and a male fin whale (B. physalus): molecular and morphological documentation. Journal of Heredity, 82(4), 269-274. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a111085

Torres, L. (2016). The Power and Beauty of Two Blue Whales Racing. National Geographic (February 3). Available at https://blog.nationalgeographic.org/2016/02/03/the-power-and-beauty-of-two-blue-whales-racing/

Tønnessen, J.N. and Johnsen, A.O. (1982). The History of Modern Whaling. Berkeley, California: University of California Press.

Vikingsson, G.A., Pike, D.G., Valdimarsson, H., Schleimer, A., Gunnlaugsson, Th., Silva, T., Elvarsson, B.Þ., Mikkelsen, B., Øien, N., Desportes, G., Bogason, V. and Hammond, P.S. (2015). Distribution, abundance, and feeding ecology of baleen whales in Icelandic waters: have recent environmental changes had an effect? Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 17(3). https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2015.00006

Visser F., Hartman K.L., Pierce G.J., Valavanis V.D. and Huisman J. (2011). Timing of migratory baleen whales at the Azores in relation to the North Atlantic spring bloom. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 440, 267–279. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps09349

Weir, C.R. 2023. Balaenoptera musculus (Europe assessment). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2023: e.T2477A221061186. Accessed on 19 December 2023.

Williams, T.M., Davis, R.W., Fuiman, L.A., Francis, J., Le Boeuf, B.J., Horning, M., Calambokidis, J. and Croll, D.A. (2000). Sink or Swim: Strategies for Cost-Efficient Diving by Marine Mammals. Science, 288(5463), 133–136. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.288.5463.133

Øien, N. (2019). Blåhval. Havforskningsinstituttet (July 5). Available at http://www.imr.no/hi/temasider/arter/blahval

Norwegian Polar Institute – Blue whale

Institute of Marine Research – Blåhval (in Norwegian)

Canadian Recovery Strategy for the Blue Whale, Northwest Atlantic Population

NOAA’s Draft Recovery Plan for the Blue Whale

American Cetacean Society – Blue whale

Mingan Island Cetacean Study – Blue whale

The Marine Mammal Center – Blue whales, the largest animal on Earth

Live Science – Blue whales, the most enormous creatures on Earth

Greenlandic Red list (in Danish)

Icelandic Red List (in Icelandic)

Norwegian Red List – Blåhval (in Norwegian)