White-beaked Dolphin

Latest update: March 2026

The white-beaked dolphin (Lagenorhynchus albirostris) is a large, robustly built dolphin with black, white and grey colouration that varies considerably between individuals. It has a sloping melon and a beak that is short, thick, and ranges in colour from white to dark grey and mottled. The dorsal fin is relatively tall and strongly curved. It has a northerly distribution and is found in the cold temperate and subarctic waters of the North Atlantic Ocean, in waters both on and off the continental shelf. The white-beaked dolphin may easily be misidentified as the Atlantic white-sided dolphin (Leucopleurus acutus) as their ranges overlap considerably; until 2025, they were even placed in the same genus. The white-beaked dolphin is typically larger than the white-sided dolphin and lacks the yellow streaks on its side that the white-sided has. White-beaked dolphins are also commonly found in waters further north than most other dolphins.

White-beaked dolphins are quite abundant in the temperate and subarctic shelf habitats of the North Atlantic Ocean, with a total population upwards of 300,000. In many regions it is the most common dolphin present.

This species has a northerly distribution and is found in the cold temperate and subarctic waters of the North Atlantic Ocean.

This species has never been subject to any commercial hunt. Small scale hunting of this species for food has occurred in Norway, Greenland, Iceland, the Faroe Islands and Canada.

As a widespread and abundant species, with no reported population declines or major threats identified, it receives little specific management attention.

In the most recent assessment (2018) the species is listed as ‘Least Concern’ on the global IUCN Red List.

LIFESPAN

Can live to be more than 30 years old.

AVERAGE SIZE

Adults are on average 240–280 cm long and weigh 200–300 kg, with males generally being longer and heavier than females.

MIGRATION AND MOVEMENTS

There appear to be some seasonal movements, with dolphins moving north in the summer months and south during the winter. In some cases, their movements seem to follow schooling capelin or other fish. Water temperature is also an important determinant of habitat use for this species.

FEEDING

Primarily piscivorous, consuming a variety of fish species, but also occasionally feeds on squid, octopus and benthic crustaceans. Cooperative feeding has been observed.

General Characteristics

The white-beaked dolphin (Lagenorhynchus albirostris) is a large, robustly built dolphin with black, white, and grey colouration. It has a short, thick rostrum or “beak” about 5 to 8 cm long in front of a sloping melon. Despite their name, the beak is not always white. In one photographic study of the species, only 7% of adults had completely white beaks (Bertulli et al. 2016a). More often, the beak is a mottled or a dark grey colour, especially in older individuals, although the tip may be white. The body is black or dark grey except behind the dorsal fin, where a pale grey to whitish area extends up from the flanks, forming a distinctive pale “saddle” or patch. This patch is often less distinct in young animals.

The underside is light grey to white in colour, while the flippers, fluke and dorsal fin are all dark grey to black, although there may be light patches on the anterior leading edges of the fin and flippers in adults. The dorsal fin is located at the mid-point of the body and is relatively tall and strongly curved. In front of the dorsal fin in some animals is a grey chevron which can extend into an irregular strip along the animal’s sides and into the dorsal patch. Around the eye is a pale ring, which may be connected to the beak by a thin, white line. Overall, there is considerable variation in colouration between individuals of this species (Lien et al. 2001, Bertulli et al. 2016a).

VARIATION BY AGE

Colouration also varies by age, and in one study, four different age-classes of dolphin: adults, juveniles, calves, and neonates could be distinguished based on colour pattern (Bertulli et al. 2016a). Juveniles and calves, for example, were identified by the presence of any of three colour patterns: speckling, a semicircular head blaze, and a lateral patch. In this species, speckling decreased with age and was lost completely when the dolphin became sexually mature, the opposite of most other dolphin species, in which speckles appear as the animal matures (Bertulli et al. 2016a).

MISIDENTIFICATION

The white-beaked dolphin may easily be misidentified as the Atlantic white-sided dolphin (Leucopleurus acutus), as their ranges overlap considerably. The white-beaked is typically larger than the white-sided and lacks the yellow streaks on its side that the white-sided has. The number of teeth is also different, with the white-beaked having fewer teeth than the white-sided. White-beaked dolphins are also commonly found in waters further north than other dolphins

Life History and Ecology

Behaviour

Diving and swimming

White-beaked dolphins are fast, powerful swimmers and are quite active at the water’s surface. Their local names of “jumper” or “springer” come from their common practice of breaching and leaping vertically clear out of the water.

Photo-identification and other observations of these dolphins around Iceland found that white-beaked dolphins spend much of their time travelling, with one tagged dolphin covering over 5000 km in 201 days (Rasmussen et al. 2013). They seem to be attracted to small boats and will often ride the bow or stern wave (Reeves et al. 1999, Lien et al. 2001).

The diving behaviour of this species is not well known. Only one individual has so far been tagged with a bio-logging device – a juvenile male in Faxaflói Bay in western Iceland. This animal was found to make fairly shallow dives, to a mean depth of 24 m, with its deepest dive being 45 m. The maximum dive time observed was 78 seconds, but the dives were generally shorter with a mean duration of 28 seconds (Rasmussen et al. 2013).

Social behaviour

White-beaked dolphins generally travel in small pods of less than 10 individuals. During the 2016 SCANS III survey of the North Sea, the mean group size seen was 3.86 (Hammond et al. 2017). It is not unusual , however, to see larger groups of several hundred, or even thousands, of animals (Dong et al. 1996, Reeves et al. 1999, Lien et al. 2001). Groups in some cases appear to be segregated by age and sex (Evans & Smeenk 2008), with groups of juveniles separated from groups of adults with calves.

Cooperative feeding has been observed in white-beaked dolphins, with the dolphins working together to herd or encircle schools of fish and trap them at the water’s surface (Reeves et al. 1999, Evans and Smeenk 2008). They also seem to associate with certain species of whales, especially fin, sei, and humpback whales, perhaps obtaining food by catching the fish that the whales miss as they surface (Reeves et al. 1999). While feeding, they may also form mixed schools with other types of dolphins such as Atlantic white-sided and bottlenose dolphins.

Sounds

White-beaked dolphins produce a variety of sounds, described as whistles, squeaks, buzzes, and clicks. Whistles may be used to identify individuals and are likely used for group members to keep in contact with each other, or for mothers and calves to keep contact. Whistles have been found to be directional and can be used at distances of up to around 10.5 km (Rasmussen et al. 2006).

Pulsed sounds such as the clicks, are primarily used for echolocation (Reeves et al. 1999), although the white-beaked dolphin has been observed to use “burst pulse” vocalizations for communication (Simard et al. 2008).

Strandings and entrapments

Mass strandings for this species are rare and seem to be less common than for white-sided dolphins (Lien et al. 2001, Waring et al. 2006). They are regularly found stranded, however, this is more common as individuals or in small groups of 2–7 animals. These dolphins are in fact one of the most frequently stranded cetaceans along the North Sea coast of the UK (Reeves et al. 1999), although the number of reported strandings has steadily declined since the 1970s (Canning et al. 2008).

White-beaked dolphins also occasionally become trapped in moving pack ice and may die due to drowning or being crushed by the ice. In Svalbard, one such incident led to the dolphins becoming prey for polar bears (Aars et al. 2015). Around Newfoundland, 29 entrapment events were recorded between 1979–1991, with up to 350 dolphins killed during this time (Dong et al. 1996).

Life History

At birth, white-beaked dolphins are around 110–120 cm long and 40 kg in weight (Lien et al. 2001, Evans & Smeek 2008). They grow quickly up to age 3, with males growing faster than females (Dong et al. 1996). Adult males are larger than females, averaging 250–280 cm and 250–300 kg, with the longest male recorded being 310 cm. The heaviest reported male was 354 kg. Adult females generally range in length from 240–270 cm and weigh 200–250 kg. The heaviest female seen was 306 kg, although a pregnant female was found that weighed 387 kg (Reeves et al. 1999, Evans & Smeek 2008).

White-beaked dolphin in Kolgrafafjörður, near the small fishing village of Grundarfjörður, Iceland. © AlecOwenEvans/iStock

Reproduction

The biology of this species is not well known, but both mating and parturition are thought to occur during the summer months (Galatius & Kinze 2016). In one study, testes weights of stranded males found between mid-April and late August were more than double the “baseline” weights for mature males, suggesting that breeding occurs at this time (Galatius et al. 2013).

Strandings of newborns and very young calves are reported almost exclusively between June and September, which seems to indicate that births occur during that time (Lien et al. 2001, Canning et al. 2008). Females give birth to one calf after a gestation period of about 11 months (Reeves et al. 1999). It is not known if a female produces a calf each year, or if there is a resting period between calves.

White-beaked dolphin females become sexually mature somewhere between 6–10 years old, at a length of 230–250 cm (Evans & Smeek 2008, Galatius & Kinze 2016). Males become sexually mature around 2 years later than females, between 8–12 years old, and generally between 230–260 cm in length. There appears to be considerable variation in age and size at sexual maturity for both males and females (Dong et al. 1996), with one study finding an immature male that was 16 years old (Galatius et al. 2013). White-beaked dolphins can live to be over 30 years.

Food and feeding

White-beaked dolphins are primarily piscivorous, consuming a variety of fish species. In one study, 25 different species of fish were found in dolphin stomach contents (Jansen et al. 2010). Some of the main types of fish that these dolphins eat are species of Clupea, Mallotus, Gadus, Merlangius, Melanogrammus, Trisopterus, Eleginus, Merluccius, Trachurus, Scomber, as well as various species of Ammodytidae, Gobiidae, Soleidae, Pleuronectidae, and Bothidae (Evans & Smeenk 2008). While they will eat a variety of fish, some of the larger species dominate the diet, particularly Gadidae.

In the only long-term study of white-beaked dolphin diet, in which stranded animals were examined over a 35 year period, no overall change in the diet was observed, nor any clear differences in the diet between different sexes or size-classes of dolphins (Jansen et al. 2010).

Dominant prey by area

In a study of 45 white-beaked dolphins stranded on the Dutch coast between 1968 and 2005, Gadidae, particularly whiting (Merlangius) and cod (Gadus), were found in every stomach and were the dominant component of the diet by both weight (98%) and number (40%) (Jansen et al. 2010). Other studies of the diet of white-beaked dolphins from both the North Sea and Newfoundland found cod (Gadus morhua), whiting (Merlangius merlangus), and hake (Merluccius merluccius) to be the dominant prey items (Reeves et al. 1999, Evans & Smeenk 2008). Off Newfoundland, 90% of the dolphin stomachs examined contained otoliths or bones from cod (Dong et al. 1996). Dolphins stranded on the Scottish east coast had stomachs that contained predominantly haddock (Melanogrammus) and whiting (Canning et al. 2008).

In West Greenland, fish species such as capelin (Mallotus villosus), sandeel (Ammodytes sp), and haddock are important components in the diet of these dolphins (Hansen & Heide-Jørgensen 2013). They have also been observed feeding on capelin off south-eastern Greenland (Reeves et al. 1999). Dolphins in Iceland have a similar diet, with larger fish such as haddock, cod, and saithe (Pollachius virens) as the most important constituents (Víkingsson & Olafsdóttir 2004 in Galatius & Kinze 2016). A study by Samarra et al. (2022) corroborated this, with herring, capelin, and sandeel (in decreasing order of proportion in the diet) also being consumed.

Other prey items

In addition to fish, white-beaked dolphins occasionally feed on squid, octopus, and benthic crustaceans (Reeves et al. 1999, Lien et al. 2001, Evans & Smeenk 2008). Remains of seaweed were also found in a few dolphin stomachs from Newfoundland (Dong et al. 1996).

Predators

White-beaked dolphins have few natural predators. The killer whale (Orcinus orca) appears to be their main predator, with rake marks, probably from these whales, found on the back and flanks of some dolphins in Icelandic waters (Bertulli et al. 2012). Some wounds found on white-beaked dolphins also appeared to be caused by conspecifics (Bertulli et al. 2016b).

In Svalbard, a polar bear was observed feeding on two white-beaked dolphins (Aars et al. 2015). The dolphins were part of a small pod that had become trapped in ice and were probably killed by the bear as they were forced to surface for air.

Health – diseases and parasites

White-beaked dolphins may become infected with various bacteria, viruses, and parasites. A thorough description may be found in Galatius and Kinze (2016). Infections in the jaws and teeth of stranded dolphins are often noted (Lien et al. 2001), which are thought to be due to old age. Infections may also be present on the skin. Among 76 white-beaked dolphins observed in Faxaflói Bay, western Iceland, 56 (or 73.7%) had at least one skin condition (Bertuilli et al.2012), with “tattoo-like” lesions and traumas most often seen.

These dolphins also seem to be susceptible to spinal deformities, with fused vertebrae and other conspicuous vertebral malformations found in stranded individuals (Galatius et al. 2009, Bertulli et al. 2015b).

Like many other marine mammals, white-beaked dolphins often contain parasites such as tapeworms and various nematodes (Lien et al. 2001, Galatius & Kinze 2016).

Distribution and habitat

The white-beaked dolphin has a northerly distribution and is found in the cold temperate and subarctic waters of the North Atlantic Ocean. In the Northwest Atlantic, they are found around southern Greenland and into the Davis Strait. They very rarely occur on the western side of Davis Strait, with only 2 individuals sighted off southern Baffin Island between 2004 and 2013 (Reinhart et al. 2014). The species is common along the coast of Labrador in the summer and fall, and ranges as far south as Cape Cod, Massachusetts, in the winter and spring (Dong et al. 1996, Evans & Smeek 2008).

In the northeastern Atlantic, white-beaked dolphins are common around Iceland, east to Svalbard and Novaya Zemlya in the Barents Sea. They are also found along portions of the Atlantic coast of Norway and south to Denmark. They occur in the Kattegat, between Denmark and Sweden, but rarely go into the Baltic Sea. White-beaked dolphins are found all around the British Isles and along parts of the Atlantic coast of Ireland. They have been reported as far south as 47°N along the French coast, and there have been rare sightings off Spain and Portugal (Reeves et al. 1999).

Habitat

The white-beaked dolphin is pelagic and can be found in waters both on and off the continental shelf, although there is evidence suggesting that they prefer waters less than 200 m deep (Evans & Smeenk 2008, Hammond et al. 2012). In a study of the Barents Sea, dolphin density peaked at depths of 150–200 m, but also at depths of around 400 m (Fall and Skern-Mauritzen 2014). Off the coasts of Newfoundland and Labrador, sightings of these dolphins are more common in nearshore waters than offshore, but that may just be due to the greater amount of human activity near shore resulting in more sightings (Lien et al. 2001).

In other areas, they are found in deeper waters. Off the West Greenland shelf, large groups of this species were associated with depths of 300–1,000 m and smaller groups were found over even deeper waters (Hansen & Heide-Jørgensen 2013).

The species is highly mobile and transient and can range over large ocean areas (Bertulli et al. 2015a).

Migrations and movements

A change in habitat use has been documented in U.S. waters, where white-beaked dolphins were observed mainly on the continental shelf prior to the 1970s but were primarily found over slope waters during the 1970s. This shift appeared to be associated with changes in the abundance of some of their fish prey species, as well as a change in the distribution of Atlantic white-sided dolphins, Leucopleurus acutus (Waring et al. 2006).

There appear to be some seasonal movement with dolphins moving north in the summer months and south during the winter. This is seen both along the coasts of Labrador (Lien et al. 2001) and West Greenland (Hansen & Heide-Jørgensen 2013). In some cases, their movements seem to follow schooling capelin or other fish (Lien et al. 2001). While travelling, they are generally found in small groups, however they can congregate in larger numbers in good feeding areas (Hansen & Heide-Jørgensen 2013).

There is some evidence that female white-beaked dolphins may move into nearshore waters to give birth. This is suggested by a peak in calf strandings in UK waters during the summer months, which coincides with a peak in female strandings (Canning et al. 2008).

Water temperature is also an important determinant of habitat use for this species. White-beaked dolphins appear to prefer cooler waters, with their occurrence decreasing significantly in water temperatures greater than around 12–14°C (Tetley & Dolman 2013). This has also been suggested as a factor in white-beaked dolphin movements around the UK, with dolphin distribution shifting northwards perhaps due to increasing water temperatures in the south (Canning et al. 2008).

North Atlantic stocks

The white-beaked dolphin has a wide range across the North Atlantic Ocean. Across this range, there appear to be four areas with higher densities of dolphins: off the Labrador Shelf in the Northwest Atlantic and around southwestern Greenland; around Iceland; around the northern part of the British Isles and the North Sea; and the shelf along the Norwegian coast and into the Barents Sea (Kinze 2009).

A recent genomic study by Gose et al. (2024) found evidence of population structure, with four different stocks identified: the western North Atlantic, Iceland and the Barents Sea, the North Sea, and west Scotland and Ireland. At present, it is unclear which stock(s) the white-beaked dolphins in East and West Greenland belong to, as genetic analyses have not yet been performed on these animals. The low genetic connectivity between the eastern and western North Atlantic confirms earlier findings by Mikkelsen and Lund (1994), who found differences in skull morphometrics between white-beaked dolphins from the eastern (North Sea and English Channel) and western North Atlantic (US coast). This difference is also in line with an earlier genetic study looking at mitochondrial and microsatellite DNA variation (Banguera-Hinestroza et al. 2010).

Based on these studies and the distribution patterns observed over decades of sighting surveys, the NAMMCO Working Group on Dolphins delineated four management areas for this species: 1) Western North Atlantic (Canadian and northern US waters); 2) Icelandic waters; 3) Northern Norway; and 4) around the British Isles and all of the North Sea (NAMMCO 2023).

Current abundance and trends

There are some population estimates available for white-beaked dolphins in different parts of their range. Generally, however, the population has not been extensively surveyed, with most estimates arising from surveys where other species were the primary target.

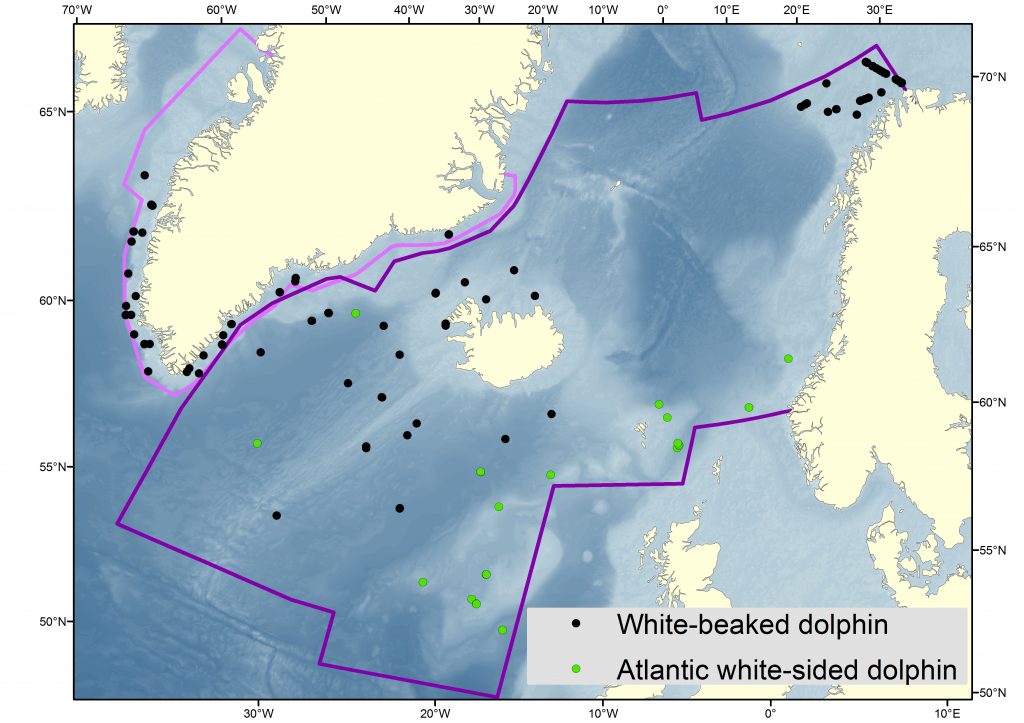

Sightings of white-sided and white-beaked dolphins during NASS2015. Map: Nils Øien, IMR

Greenland

A survey was conducted in 2007 off the shelf of West Greenland as far north as 71° and up to 90 km off the coast, which gave a population estimate for white-beaked dolphins in that area of 11,984 (CV = 0.19) (Hansen & Heide-Jørgensen 2013 ). Both East and West Greenland were surveyed in 2015, with population estimates of 2,747 white-beaked dolphins (95% CI: 1,257–6,002) in West Greenland and 2,140 (95% CI: 825–5,547) in East Greenland (NAMMCO 2016).

Iceland

White-beaked dolphins are considered common in the waters around Iceland. From the North Atlantic Sightings Surveys (NASS) conducted in 2001, a population estimate of 31,653 (95% CI 17,679–56,672) was calculated (Pike et al. 2009). This estimate did include other dolphin species, although the overwhelming majority of the sightings were white-beaked dolphins. The Icelandic and Faroese components of the Trans North Atlantic Sightings Survey (T-NASS) ship surveys conducted in 2007 resulted in an estimate of 91,277 white beaked dolphins (95% CI: 32,351–257,537) (NAMMCO 2019).

A series of aerial surveys around Iceland have also produced estimates for white-beaked dolphins (see NAMMCO 2019 for all endorsed estimates). In 2007, sightings during the CIC aerial survey led to an abundance estimate of 46,683 white-beaked dolphins (95% CI: 22,409–97,251). This survey had harbour porpoises as a focal species and was therefore flown at a lower altitude than the other surveys that followed. In 2009, the estimated abundance from the CIC aerial survey was 75,959 (95% CI: 26,366–218,834). In 2016, the estimated abundance from the CIC aerial survey was 59,966 (95% CI: 24,907–144,377). All of these estimates from the aerial surveys are considered to be negatively biased as they have not been corrected for animals submerged beyond visibility during the passage of the plane (availability bias). Performing this correction requires information on the temporal distribution of the animals in the water column, which is not presently available for this species.

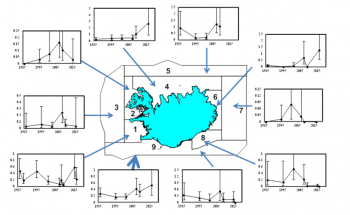

Trends in the relative abundance (uncorrected line transect density, whales nm-2) of white-beaked dolphins by stratum and for the entire survey area (thick arrow)

There has been an overall annual increase in estimated abundance for white-beaked dolphins in the survey area around Iceland from 1986 to 2016 of 0.07 (CV=0.22). This is due primarily to observed increases in the large northern blocks 4 and 5, which had the highest densities of white-beaked dolphins in the survey area in most years and positive increase rates over the period. In other strata, estimated density showed no obvious pattern with time. Since NASS ship surveys show a continuous distribution of the species offshore, the apparent increase in abundance is at least partly due to changes in distribution both inside and outside the survey area (NAMMCO 2019).

North Sea and Norway

In the North Sea, several surveys have been carried out. From ship surveys for minke whales carried out in the southern North Sea, southern Barents Sea and west to Svalbard in 1988, a population estimate of 132,000 small delphinids was calculated (95% CI: 79,000–220,000). A similar survey in 1995 gave an estimate of 91,000 (CV = 0.59) (Øien 1996). The great majority, likely 90%, of these were white-beaked dolphins, based on previous surveys where animals were identified to species level (Reeves et al. 1999). Around Iceland, 92% of the dolphins observed during the NASS surveys were white-beaked (Pike et al. 2009).

The multinational Small Cetacean Abundance in the North Sea and Adjacent Waters (SCANS) surveys were carried out in 1994, 2005, 2016, and 2022. The 1994 survey estimated 7,856 white-beaked dolphins in this area, although in the most recent report this figure has been revised to 23,716. The 2005 estimate was 16,536, and this estimate has also been revised to 37,689 (Hammond et al. 2017). The 2016 estimate for white-beaked dolphins in this region is 36,287 (CV = 0.29, 95% CI: 18,694–61,869) (Hammond et al. 2017). The estimated abundance of white-beaked dolphins for 2022 in this area is 67,138 (CV = 0.325, 95% CI: 33,978–119,349) (Gilles et al., 2023)

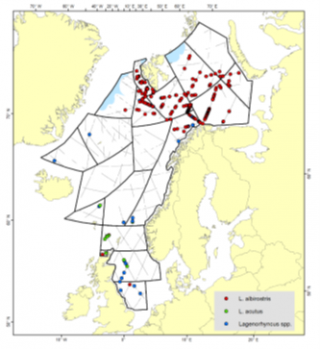

Area covered by Norwegian mosaic surveys and distribution of sightings of white-beaked and white-sided dolphins during the 2014-2018 survey

The Norwegian mosaic surveys, which cover the northern North Sea, the Norwegian Sea, the Greenland Sea, and the Barents Sea, have grouped white-beaked and white-sided dolphins together due to a lack of confidence in species identification and therefore abundance estimates from these surveys are provided at the level of the genus they both belonged to prior to 2025 (Lagenorhynchus). In 2002–2007, the Norwegian mosaic survey estimated abundance for these delphinids as 218,640 animals (95% CI: 150,330–318,000). In 2008–2013, abundance was estimated at 163,688 animals (95% CI: 112,673–237,800). In 2014–2018, abundance was estimated as being 187,482 animals (95% CI: 112,434–312, 624). All of these abundance estimates, as well as a discussion of the anonymously low estimate in the 2008–2013 cycle, can be found in the 2019 report of the NAMMCO Abundance Estimates Working Group (NAMMCO 2019).

Overall

Another population estimate was calculated for white-beaked dolphins in the Northeast Atlantic using estimates of nucleotide diversity from a recent genetics study. Fernández et al. (2016) calculated an effective population size of 61,253–88,963 individuals.

Overall, the white-beaked dolphin is quite abundant in the temperate and subarctic shelf habitats of the North Atlantic Ocean. Summing the most recent abundance estimates from different areas and taking into account the gaps between surveyed areas, the total population is likely well over 300,000 individuals.

Stock status

One of the few projects able to give an indication of possible population trends is the multinational Small Cetacean Abundance in the North Sea and Adjacent Waters (SCANS) survey project. Results of the trend analysis of population estimates for white-beaked dolphins in the North Sea show no indication of changes in abundance since 1994 (Hammond et al. 2017).

Given the considerable uncertainties around stock identity and removal rates in Greenland, it is currently not possible to conduct a full stock assessment for white-beaked dolphins. Instead, a Potential Biological Removal (PBR) approach was used by the Working Group on Dolphins (NAMMCO 2023), calculating the number of animals that can sustainably be removed from the population while allowing it to remain at or recover to adequate abundance (Wade 1998). When assessing West Greenland independently from East Greenland, Iceland, and the Faroe Islands, PBR is 31 animals for the former area and 1,661 for the latter. When assessing all areas together, PBR is 1,662 animals. In either case, recent catch statistics suggest that the removals of white-beaked dolphins in Greenland are well above the PBR threshold and are, therefore, likely unsustainable.

Iceland

In Icelandic waters, numbers of white-beaked dolphins showed little change and no trend between 1986 and 2001, as the uncorrected abundances for those years ranged from 11,717 (95% CI: 7,684–17,864) in 1995 to 18,706 (95% CI: 11,93–629,317) in 2001 (Pike et al. 2009). The most recent uncorrected NASS estimate, for 2015, is over twice that found in those surveys and is significantly larger than the 1995 estimate, although not significantly larger than the 2001 estimate (Pike et al. 2020). It is difficult, however, to say if this indicates an upwards population trend, as the surveys are unlikely to be covering an entire stock unit (if there is a separate Icelandic stock). The increase in numbers seen could be a result of changes in dolphin distribution over an area larger than that covered by the survey.

West Greenland

In West Greenland, a decline in abundance was noted between the 2007 and 2015 surveys, with the number of sightings in West Greenland in 2015 being only half of the sightings in 2007 (NAMMCO 2016). Further surveys would be needed in order to determine if this is a population trend or not. No previous estimate is available from East Greenland for comparison.

Other areas

Around the UK, there seems to be a decline in white-beaked dolphin numbers, as evidenced by numbers of strandings declining since the 1970s in all areas except in the north-east of Scotland (Canning et al. 2008). It is difficult to say whether this is a result of actual population decline though or a result of a shift in habitat use.

Management

The white-beaked dolphin is a widespread and abundant species, with no reported population declines or major threats identified. As such, it receives little specific management attention, with the meeting of the NAMMCO Working Group on Dolphins in 2023 being the first time a stock assessment was attempted for the North Atlantic.

Hunting is allowed in Greenland year-round for this species. While there are no quotas or catch limits, catch numbers are reported and monitored annually (e.g. Piniarneq 2014). Since 2007, this species has been listed in the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) regional European red list in the category of “Least Concern” (Sharpe and Berggren, 2023). The species is listed as “Least Concern” on Norwegian national red list as well.

While not considered endangered, white-beaked dolphins are listed in Appendix II of CITES, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna, as well as in Appendix II of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS). These conventions provide for international cooperation in the management of widely distributed species.

Hunting and utilisation

Historically

The white-beaked dolphin has never been subject to any commercial hunt. Small-scale hunting of this species for food has occurred in Norway, Greenland, Iceland, the Faroe Islands and Canada (Lien et al. 2001, Hammond et al. 2012).

Recent catches

Canada

In Canada, white-beaked dolphins are opportunistically hunted by communities in Newfoundland and Labrador. From interviews conducted in the 1980s, an estimated 366 dolphins were taken each year in this area, although the numbers from year to year were highly variable (Alling & Whitehead 1987).

Greenland

Hunting of this species for subsistence purposes occurs in Greenland. Catch numbers are reported each year, although data from between 1992 and 2020 are combined catches of white-beaked and Atlantic white-sided dolphins, as there was no Greenlandic name to distinguish between the two species prior to 2020. Between 2003 and 2021, a total of 2692 dolphins were taken according to the Greenlandic catch statistics. Hunting for dolphins in Greenland is opportunistic, with the numbers taken each year varying from 39 in 2007 to the peak of 381 in 2020. The average catch of dolphins between 2011 and 2015 was 160 per year, which was an increase over the previous 5 years (2006-2010) in which the average was 115 per year (NAMMCO 2016). It is not known whether this was due to an increase in the dolphin population around Greenland or if hunters are targeting dolphins more. There has been an increase in the last five years (2016-2020) with average of 193 caught animals per year.

Faroe Islands

In the Faroe Islands, white-beaked and Atlantic white-sided dolphins are occasionally taken in the drive catches traditionally done for pilot whales. Over close to 300 years (1709–1995), the reported combined numbers of Lagenorhynchus albirostris and Leucopleurus acutus hunted in the Faroe Islands was 5,148 individuals, most of which were white-sided dolphins (Bloch 1996 in Galatius & Kinze 2016). Catches of dolphins in the Faroe Islands decreased greatly after 2007, and there have been few drive hunts in recent years (NAMMCO 2015). There has not been reported any catches of white-beaked dolphins in the Faroe Islands since at least 1992.

Catches in NAMMCO member countries since 1992

| Country | Species (common name) | Species (scientific name) | Year or Season | Area or Stock | Catch Total | Quota (if applicable) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greenland | White-sided/-beaked dolphin | Lagenorhynchus spp. | 1992-2002 | Total | *No reported catches | No quota |

| Greenland | White-sided/-beaked dolphin | Lagenorhynchus spp. | 2023 | Total | 215 | No quota |

| Greenland | White-sided/-beaked dolphin | Lagenorhynchus spp. | 2022 | Total | 185 | No quota |

| Greenland | White-sided/-beaked dolphin | Lagenorhynchus spp. | 2021 | Total | 337 | No quota |

| Greenland | White-sided/-beaked dolphin | Lagenorhynchus spp. | 2020 | Total | 382 | No quota |

| Greenland | White-sided/-beaked dolphin | Lagenorhynchus spp. | 2019 | Total | 225 | No quota |

| Greenland | White-sided/-beaked dolphin | Lagenorhynchus spp. | 2018 | Total | 130 | No quota |

| Greenland | White-sided/-beaked dolphin | Lagenorhynchus spp. | 2017 | East | 42 | No quota |

| Greenland | White-sided/-beaked dolphin | Lagenorhynchus spp. | 2017 | West | 54 | No quota |

| Greenland | White-sided/-beaked dolphin | Lagenorhynchus spp. | 2017 | Total | 96 | No quota |

| Greenland | White-sided/-beaked dolphin | Lagenorhynchus spp. | 2016 | East | 50 | No quota |

| Greenland | White-sided/-beaked dolphin | Lagenorhynchus spp. | 2016 | West | 76 | No quota |

| Greenland | White-sided/-beaked dolphin | Lagenorhynchus spp. | 2016 | Total | 126 | No quota |

| Greenland | White-sided/-beaked dolphin | Lagenorhynchus spp. | 2015 | East | 27 | No quota |

| Greenland | White-sided/-beaked dolphin | Lagenorhynchus spp. | 2015 | West | 69 | No quota |

| Greenland | White-sided/-beaked dolphin | Lagenorhynchus spp. | 2015 | Total | 96 | No quota |

| Greenland | White-sided/-beaked dolphin | Lagenorhynchus spp. | 2014 | East | 35 | No quota |

| Greenland | White-sided/-beaked dolphin | Lagenorhynchus spp. | 2014 | West | 102 | No quota |

| Greenland | White-sided/-beaked dolphin | Lagenorhynchus spp. | 2014 | Total | 137 | No quota |

| Greenland | White-sided/-beaked dolphin | Lagenorhynchus spp. | 2013 | East | 44 | No quota |

| Greenland | White-sided/-beaked dolphin | Lagenorhynchus spp. | 2013 | West | 102 | No quota |

| Greenland | White-sided/-beaked dolphin | Lagenorhynchus spp. | 2013 | Total | 146 | No quota |

| Greenland | White-sided/-beaked dolphin | Lagenorhynchus spp. | 2012 | East | 25 | No quota |

| Greenland | White-sided/-beaked dolphin | Lagenorhynchus spp. | 2012 | West | 155 | No quota |

| Greenland | White-sided/-beaked dolphin | Lagenorhynchus spp. | 2012 | Total | 180 | No quota |

| Greenland | White-sided/-beaked dolphin | Lagenorhynchus spp. | 2011 | East | 29 | No quota |

| Greenland | White-sided/-beaked dolphin | Lagenorhynchus spp. | 2011 | West | 208 | No quota |

| Greenland | White-sided/-beaked dolphin | Lagenorhynchus spp. | 2011 | Total | 237 | No quota |

| Greenland | White-sided/-beaked dolphin | Lagenorhynchus spp. | 2010 | East | 18 | No quota |

| Greenland | White-sided/-beaked dolphin | Lagenorhynchus spp. | 2010 | West | 243 | No quota |

| Greenland | White-sided/-beaked dolphin | Lagenorhynchus spp. | 2010 | Total | 261 | No quota |

| Greenland | White-sided/-beaked dolphin | Lagenorhynchus spp. | 2009 | East | 5 | No quota |

| Greenland | White-sided/-beaked dolphin | Lagenorhynchus spp. | 2009 | West | 87 | No quota |

| Greenland | White-sided/-beaked dolphin | Lagenorhynchus spp. | 2009 | Total | 92 | No quota |

| Greenland | White-sided/-beaked dolphin | Lagenorhynchus spp. | 2008 | East | 2 | No quota |

| Greenland | White-sided/-beaked dolphin | Lagenorhynchus spp. | 2008 | West | 106 | No quota |

| Greenland | White-sided/-beaked dolphin | Lagenorhynchus spp. | 2008 | Total | 108 | No quota |

| Greenland | White-sided/-beaked dolphin | Lagenorhynchus spp. | 2007 | East | 1 | No quota |

| Greenland | White-sided/-beaked dolphin | Lagenorhynchus spp. | 2007 | West | 38 | No quota |

| Greenland | White-sided/-beaked dolphin | Lagenorhynchus spp. | 2007 | Total | 39 | No quota |

| Greenland | White-sided/-beaked dolphin | Lagenorhynchus spp. | 2006 | East | 2 | No quota |

| Greenland | White-sided/-beaked dolphin | Lagenorhynchus spp. | 2006 | West | 67 | No quota |

| Greenland | White-sided/-beaked dolphin | Lagenorhynchus spp. | 2006 | Total | 69 | No quota |

| Greenland | White-sided/-beaked dolphin | Lagenorhynchus spp. | 2005 | East | 3 | No quota |

| Greenland | White-sided/-beaked dolphin | Lagenorhynchus spp. | 2005 | West | 23 | No quota |

| Greenland | White-sided/-beaked dolphin | Lagenorhynchus spp. | 2005 | Total | 26 | No quota |

| Greenland | White-sided/-beaked dolphin | Lagenorhynchus spp. | 2004 | East | N/A | No quota |

| Greenland | White-sided/-beaked dolphin | Lagenorhynchus spp. | 2004 | West | N/A | No quota |

| Greenland | White-sided/-beaked dolphin | Lagenorhynchus spp. | 2004 | Total | N/A | No quota |

| Greenland | White-sided/-beaked dolphin | Lagenorhynchus spp. | 2003 | East | 3 | No quota |

| Greenland | White-sided/-beaked dolphin | Lagenorhynchus spp. | 2003 | West | 4 | No quota |

| Greenland | White-sided/-beaked dolphin | Lagenorhynchus spp. | 2003 | Total | 7 | No quota |

This database of reported catches is searchable, meaning you can filter the information by for instance country, species or area. It is also possible to sort it by the different columns, in ascending or descending order, by clicking the column you want to sort by and the associated arrows for the order. By default, 30 entries are shown, but this can be changed in the drop-down menu, where you can decide to show up to 100 entries per page.

Lagenorhynchus spp. refers to animals that could be either white-beaked or white-sided dolphins, for catches prior to 2025.

Carry-over from previous years are included in the quota numbers, where applicable.

You can find the full catch database with all species here.

For any questions regarding the catch database, please contact the Secretariat at nammco-sec@nammco.no.

Other human impacts

By-catch

White-beaked dolphins may become caught in the gill nets or trawls used in commercial fisheries. Scars or wounds suspected to have resulted from entanglement in fishing gear were seen in 15 of 90 photo-identified white-beaked dolphins off Iceland (Bertulli et al. 2012). In some cases, entanglement leads to death of the dolphins by drowning. Such by-catch was reported to be “common” in Newfoundland and Labrador (Dong et al. 1996) but was thought to be under-reported as the dolphins did little damage to the gear. Because the extent of by-catch of this species is unknown, it is difficult to state whether or not it has any impact on the population.

Struck and lost

During the small-scale hunting of these dolphins, some animals that are hit may not be retrieved. This is referred to as struck and lost. Fishermen interviewed along the Newfoundland and Labrador coasts reported a struck and lost rate of 25–50% (Alling & Whitehead 1987). Estimates from hunting in other areas have not been reported, although a preliminary analysis of videos of a rifle hunt in West Greenland suggests that the struck and lost rates using this method may be quite high (NAMMCO 2023).

Noise/disturbance

White-beaked dolphin in Kolgrafafjörður, near the small fishing village of Grundarfjörður, Iceland. © AlecOwenEvans/iStock

Because white-beaked dolphins use sound to communicate, any noise from human activities may interfere with their behaviour. This has been seen, for example, in their response to noise from airguns used in seismic surveys (Stone & Tasker 2006). Other potential sources of disturbance could be activities such as shipping, oil and gas exploration, or any other human activity occurring in their habitat.

Contaminants

Both heavy metals and organochlorines have been found in white-beaked dolphin tissue samples from across the species’ range. In samples from Newfoundland, concentrations of both heavy metals and organochlorines were substantially higher in white-beaked dolphins than in other cetaceans (Muir et al. 1988). The main types of organochlorines detected were DDTs, PCBs, toxaphenes and chlordanes.

Similar contaminants were found in white-beaked dolphins from the North Sea – PCBs and heptachlor epoxide (Lien et al. 2001).

The possible effects of these pollutants are not known for this species, nor what “safe” levels of these compounds might be.

Climate change

White-beaked dolphin distribution appears to depend heavily on water temperature. This species seems to prefer cooler waters, with their occurrence decreasing significantly in water temperatures greater than 12–14°C (Tetley & Dolman 2013). Water temperature has also been suggested as a factor in white-beaked dolphin movements around the UK, with dolphin distribution shifting northwards (Canning et al. 2008) and declining on the west coast of Scotland (MacLeod et al. 2005), due to rising water temperatures.

If water temperatures increase due to global climate change, this could have an impact on the distribution and habitat available for these dolphins, particularly in northwestern Europe, where the area of suitable shelf waters may be dramatically reduced (MacLeod et al. 2005). In some areas, the white-beaked dolphin could become displaced by other species, such as the common dolphin, which prefer warmer waters (MacLeod et al. 2008). Other possible consequences of changing water temperatures include redistribution of the dolphin’s prey species, and the introduction of new diseases or parasites. Sea lampreys, for example, have recently been observed on white-beaked dolphins in Icelandic waters for the first time (Bertulli et al. 2016b).

Research in NAMMCO member countries

NAMMCO member countries work cooperatively on projects such as the North Atlantic Sightings Survey (NASS) to obtain population estimates for white-beaked dolphins in member country waters. Norway has also participated in the multinational Small Cetacean Abundance in the North Sea and Adjacent Waters (SCANS) surveys.

Much research is being done in Iceland on white-beaked dolphins, including life history, ecology, and behaviour. The Húsavik Research Centre (HRC) runs long-term photo-identification and sightings studies of white-beaked dolphins in Skjálfandi Bay. Since 2018, Continuous Porpoise Detectors (C-PODS) have been deployed each year in the bay for detection of white-beaked dolphins (National Progress Report Iceland 2018, 2019, 2020). Efforts to estimate by-catch rates in fisheries are also ongoing. In 2020, the University of Iceland (UI) and the Marine and Freshwater Research Institute (MFRI) have analysed samples of stranded or bycaught white-beaked dolphins from the MFRI tissue bank to investigate their trophic ecology (National Progress Report Iceland 2020). This was done as part of a larger study that investigates the diet of killer whales.

Aars, J., Andersen, M., Breniėre, A. et al. (2015) .White-beaked dolphins trapped in the ice and eaten by polar bears. Polar Research, 34, 26612. http://dx.doi.org/10.3402/polar.v34.26612

Alling, A. K. and Whitehead, H. P. (1987). A preliminary study of the status of White-beaked Dolphins, Lagenorhynchus albirostris, and other small cetaceans off the coast of Labrador. Canadian Field-Naturalist, 101, 131–135.

Banguera-Hinestroza, E., Bjørge, A., Reid, R. J. et al. (2010). The influence of glacial epochs and habitat dependence on the diversity and phylogeography of a coastal dolphin species: Lagenorhynchus albirostris. Conservation Genetics, 11, 1823–1836. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10592-010-0075-y

Bertulli, C. G., Cechetti, A., van Bressem, M.-F. et al. (2012). Skin disorders in common minke whales and white-beaked dolphins off Iceland, a photographic assessment. Journal of Marine Animals and Their Ecology, 5, 29–40. Available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/236239009

Bertulli, C. G., Tetley, M. J., Magnúsdóttir, E. E. et al. (2015a). Observations of movement and site fidelity of white-beaked dolphins (Lagenorhynchus albirostris) in Icelandic coastal waters using photo-identification. Journal of Cetacean Research and Management, 15, 27–34. https://archive.iwc.int/pages/search.php?search=%21collection15&k=

Bertulli, C. G., Galatius, A., Kinze, C. C. et al. (2015b). Vertebral column deformities in white-beaked dolphins from the eastern North Atlantic. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms, 116, 59–67. https://doi.org/10.3354/dao02904

Bertulli, C. G., Galatius, A., Kinze, C. C. et al. (2016a). Color patterns in white-beaked dolphins (Lagenorhynchus albirostris) from Iceland. Marine Mammal Science, 32(3), 1072–1098. https://doi.org/10.1111/mms.12312

Bertulli, C. G., Rasmussen, M. H. and Rosso, M. (2016b). An assessment of the natural marking patterns used for photo-identification of common minke whales and white-beaked dolphins in Icelandic waters. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 96(4), 807–819. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025315415000284

Canning, S., Santos, M., Reid, R. et al. (2008). Seasonal distribution of white-beaked dolphins (Lagenorhynchus albirostris) in UK waters with new information on diet and habitat use. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 88(6), 1159–1166. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025315408000076

Dong, J. H., Lien, J., Nelson, D. et al. (1996). A contribution to the biology of the white-beaked dolphin, Lagenorhynchus albirostris, in waters off Newfoundland. Canadian Field-Naturalist, 110, 278–287.

Evans, P. G. H. and Smeenk, C. (2008). Genus Lagenorhynchus. In S. Harris and D. W. Yalden (eds.), Mammals of the British Isles, 724–727. Southampton, United Kingdom: The Mammal Society.

Evans, P. G. H. and Teilmann, J. (eds.). (2009). Report of ASCOBANS/HELCOM small cetacean population structure workshop. Bonn, Germany: ASCOBANS 141 pp.

Fall, J. and Skern-Mauritzen, M. (2014). White-beaked dolphin distribution and association with prey in the Barents Sea. Marine Biology Research, 10(10), 957–971. https://doi.org/10.1080/17451000.2013.872796

Fernández, R., Schubert, M. , Vargas-Velázquez, A. M. et al. (2016). A genomewide catalogue of single nucleotide polymorphisms in white-beaked and Atlantic white-sided dolphins. Molecular Ecology Research, 16(1), 266–276. https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.12427

Galatius, A. and Kinze, C. C. (2016). Lagenorhynchus albirostris (Cetacea: Delphinidae). Mammalian Species, 48(933), 35–47. https://doi.org/10.1093/mspecies/sew003

Galatius, A., Sonne, C., Kinze, C. C. et al. (2009). Occurrence of vertebral osteophytosis in a museum sample of white-beaked dolphins (Lagenorhynchus albirostris) from Danish waters. Journal of Wildlife Diseases, 45(1), 19-28. https://doi.org/10.7589/0090-3558-45.1.19

Galatius, A., Jansen, O. E. and Kinze, C. C. (2013). Parameters of growth and reproduction of white-beaked dolphins (Lagenorhynchus albirostris) from the North Sea. Marine Mammal Science, 29(2), 348–355. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-7692.2012.00568.x

Gilles, A, Authier, M, Ramirez-Martinez, NC, Araújo, H, Blanchard, A, Carlström, J, Eira, C, Dorémus, G, Fernández-Maldonado, C, Geelhoed, SCV, Kyhn, L, Laran, S, Nachtsheim, D, Panigada, S, Pigeault, R, Sequeira, M, Sveegaard, S, Taylor, NL, Owen, K, Saavedra, C, Vázquez-Bonales, JA, Unger, B, Hammond, PS (2023). Estimates of cetacean abundance in European Atlantic waters in summer 2022 from the SCANS-IV aerial and shipboard surveys. Final report published 29 September 2023. 64 pp. https://www.tiho-hannover.de/itaw/scans-iv-survey

Gose, MA., Humble, E., Brownlow, A. et al. Population genomics of the white-beaked dolphin (Lagenorhynchus albirostris): Implications for conservation amid climate-driven range shifts. Heredity 132, 192–201 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41437-024-00672-7

Hammond, P. S., Bearzi, G., Bjørge, A. et al. (2012). Lagenorhynchus albirostris. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2012: e.T11142A17875454. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2012.RLTS.T11142A17875454.en

Hammond, P. S., Lacey, C., Gilles, A. et al. (2017). Estimates of cetacean abundance in European Atlantic waters in summer 2016 from the SCANS-III aerial and shipboard surveys. Report May 2017.

Hansen, R. G. and Heide-Jørgensen, M. P. (2013). Spatial trends in abundance of long-finned pilot whales, white-beaked dolphins and harbour porpoises in West Greenland. Marine Biology, 160, 2929–2941. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-013-2283-8

Jansen, O. E., Leopold, M. F., Meesters, E. H. W. G. et al. (2010). Are white-beaked dolphins Lagenorhynchus albirostris food specialists? Their diet in the southern North Sea. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 90(8), 1501–1508. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025315410001190

Kingsley, M. C. S. and Reeves, R. R. (1998). Aerial surveys of cetaceans in the Gulf of St. Lawrence in 1995 and 1996. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 76(8), 1529–1550. https://doi.org/10.1139/z98-054

Kinze, C. C. (2009). White-beaked dolphin Lagenorhynchus albirostris. In W. F. Perrin, B. Würsig, and J. G. M. Thewissen (eds.), Encyclopedia of marine mammals, 2nd ed., 1254–1258. SanDiego, California: Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-373553-9.00285-6

Lawson, J. W. and Gosselin, J.-F. (2009). Distribution and preliminary abundance estimates for cetaceans seen during Canada’s marine megafauna survey – a component of the 2007 TNASS. DFO Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat, Res. Doc. 2009/031. http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/csas-sccs/publications/resdocs-docrech/2009/2009_031-eng.htm

Lien, J., Nelson, D. and Hai, D. J. (2001). Status of the White-beaked Dolphin, Lagenorhynchus albirostris, in Canada. Canadian Field-Naturalist, 115(1), 118–126.

MacLeod, C. D., Bannon, S. M., Pierce, D. J. et al. (2005). Climate change and the cetacean community of north-west Scotland. Biological Conservation, 124(4), 477–483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2005.02.004

MacLeod, C. D., Weir, C. R., Begoña Santos, M. et al. (2008). Temperature-based summer habitat partitioning between white-beaked and common dolphins around the United Kingdom and Republic of Ireland. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 88(6), 1193–1198. https://doi.org/10.1017/S002531540800074X

Mikkelsen, A. M. H. and Lund, A. (1994). Intraspecific variation in the dolphins Lagenorhynchus albirostris and L. acutus (Mammalia, Cetacea) in metrical and nonmetrical skull characters, with remarks on occurrence. Journal of Zoology, 234(2), 289–299. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7998.1994.tb06076.x

Muir, D. C. G., Wagemann, R., Grift, N. P. et al. (1988). Organochlorine chemical and heavy metal contaminants in white-beaked dolphins (Lagenorhynchus albirostris) and pilot whales (Globicephala malaena) from the coast of Newfoundland, Canada. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 17, 613–629. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01055830

NAMMCO-North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (2023). Report of the Scientific Committee Working Group on Dolphins, October 2023, Copenhagen, Denmark. Available at https://nammco.no/dwg_reports/

North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO). (2016). Report of the 23rd Scientific Committee Meeting, Nuuk, Greenland. Available at https://nammco.no/topics/scientific-committee-reports/

North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO). (2019). Report of the Abundance Estimates Working Group, Tromsø, Norway. Available at https://nammco.no/topics/abundance_estimates_reports/

Øien, N. (1996). Lagenorhynchus species in Norwegian waters as revealed from incidental observations and recent sighting surveys. Cambridge, UK: International Whaling Commission.

Pike, D. G., Paxton, C. G. M., Gunnlaugsson, T. et al. (2009.) Trends in distribution and abundance of cetaceans from aerial surveys in Icelandic coastal waters, 1986–2001. NAMMCO Scientific Publications, 7, 117-142. https://doi.org/10.7557/3.2710

Pike, D. G., Gunnlaugsson, T., Sigurjonsson, J. and Víkingsson, G. (2020). Distribution and Abundance of Cetaceans in Icelandic Waters over 30 Years of Aerial Surveys. NAMMCO Scientific Publications, 11. https://doi.org/10.7557/3.4805

Piniarneq. (2014). Jagtinformation og fangstregistrering. Government ofGreenland, Nuuk, Greenland.

Rasmussen, M. H., Lammers, M., Beedholm, K. et al. (2006). Source levels and harmonic content of whistles in white-beaked dolphins (Lagenorhynchus albirostris). Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 120, 510–517. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.2202865

Rasmussen, M. H., Akamatsu, T., Teilmann, J. et al. (2013). Biosonar, diving and movements of two tagged white-beaked dolphin in Icelandic waters. Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 88–89, 97–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr2.2012.07.011

Reeves, R. R., Smeenk, C., Kinze, C. C. et al. (1999). White-beaked dolphin Lagenorhynchus albirostris Gray, 1846. In S. H. Ridgway and R. Harrison (eds.), Handbook of marine mammals, Vol. 6: The second book of dolphins and the porpoises, 1–30. Academic Press.

Reinhart, N. R., Fortune, S. M. E., Richard, P. R. et al. (2014). Rare sightings of white-beaked dolphins (Lagenorhynchus albirostris) off south-eastern Baffin Island, Canada. Marine Biodiversity Records, 7, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755267214001031

Samarra, F.I.P., Borrell, A., Selbmann, A., et al. (2022) Insights into the trophic ecology of white-beaked dolphins Lagenorhynchus albirostris and harbour porpoises Phocoena phocoena in Iceland. Marine Ecology Progress Series 702:139-152. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps14208

Sharpe, M. & Berggren, P. 2023. Lagenorhynchus albirostris (Europe assessment). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2023: e.T11142A219011385. Accessed on 12 January 2024.

Simard, P., Mann, D. and Gowans, S. (2008). Burst-pulse sounds recorded from white-beaked dolphins (Lagenorhynchus albirostris). Aquatic Mammals, 34(4), 464–470. https://doi.org/10.1578/AM.34.4.2008.464

Stone, C. J. and Tasker, M. L. (2006). The effects of seismic airguns on cetaceans in UK waters. Journal of Cetacean Research and Management, 8, 255–263. https://archive.iwc.int/pages/search.php?search=%21collection15&k=

Tetley, M. J. and Dolman, S. J. (2013). Towards a Conservation Strategy for White-beaked Dolphins in the Northeast Atlantic. Report from the European Cetacean Society’s 27th Annual Conference Workshop, The Casa da Baía, Setúbal, Portugal. European Cetacean Society Special Publication Series No. XX, 121pp.

Wade, P. R. (1998). Calculating limits to the allowable human-caused mortality of cetaceans and pinnipeds. Marine Mammal Science, 14, 1–37.

Waring, G. T., Josephson E., Fairfield, C. P. et al. (eds). (2006). U.S. Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico Marine Mammal Stock Assessments – 2005. NOAA Tech.Memo.NMFS-NE 194; 346 pp. Available at https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/tags/marine-mammal-stock-assessments

Waring, G. T., Josephson, E., Fairfield-Walsh, C. P. et al. (2008). U.S. Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico Marine Mammal Stock Assessments – 2008. NOAA Tech Memo NMFS- NE 210; 440 pp. Available at https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/tags/marine-mammal-stock-assessments

ASCOBANS – White-beaked dolphin

Greenland Institute of Natural Resources – white-beaked dolphin

International Union for the Conservation of Nature – white-beaked dolphin

Mingan Island Cetacean Study – white-beaked dolphin

Norwegian Polar Institute – white-beaked dolphin

Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society – white-beaked dolphin