Narwhal

Updated: July 2025

The narwhal is a medium-sized toothed whale that belongs to the family Monodontidae. The only other member of this family is the beluga. Narwhals have stout, torpedo-shaped bodies with a low dorsal ridge in place of a dorsal fin, and a concave-shaped tail fin. Like belugas, narwhals have short paddle-shaped front flippers, but they lack their extremely flexible neck and well-defined beak. At birth, narwhals are grey to greyish-blue in colour. They become darker and more mottled as they grow older, with white patches developing from their abdomen to up over their backs. Adult narwhals are usually light grey in colour, with a mottled pattern of darker markings over a lighter background. Very old narwhals become almost completely white. Male narwhals develop a tusk, which is a modified canine tooth that grows out the left side of the jaw, twisting anti-clockwise to form a spiral.

Abundance

An approximate estimate of global abundance is 85,000–100,000 animals (NAMMCO 2017).

Distribution

Narwhals are found in Arctic waters in areas that are seasonally ice-covered. They are found in the northern waters of Canada, Greenland, Norway, and Russia.

Relation to Humans

Narwhals are hunted for their tusks and for their meat and skin in Canada and Greenland. There is a commercial domestic trade for narwhal skin (mattak) in Greenland. The sustainable utilisation of narwhals has recently been subject of intense debate in Greenland, NAMMCO, and internationally (Heide-Jørgensen et al. 2020a).

Conservation and Management

There is an international management regime under the Joint Commission for the Conservation and Management of Narwhal and Beluga (JCNB) and NAMMCO. In West Greenland, hunting quotas have been introduced and present harvests are within sustainable limits. Narwhal in Northeast Greenland are protected within the boundaries of the world’s largest National Park. In East Greenland, narwhal aggregations are considered to be small, depleted, and declining. Noting this, as well as the impacts of climate change on the species, in 2019 the NAMMCO Scientific Committee recommended that catches in all management areas in East Greenland be reduced to zero. In 2022, the NAMMCO Scientific Committee reiterated this recommendation and stressed that there is a significant threat of extinction from a continued hunt.

In the most recent assessment (2023) the species is listed as being of ‘Least Concern’ on the regional European IUCN Red List. On the Norwegian red list, the species is listed as ‘Vulnerable’, while the Greenlandic red list places the West Greenland Narwhal population in the ‘Near Threatened’ category and the East Greenland population under ‘Endangered’.

Close up of male narwhal in water showing ivory tooth. © Carsten Engvang

Scientific name: Monodon monoceros

Faroese: Náhvalur

Greenlandic: Qilalugaq qernertaq

Icelandic: Náhvalur

Norwegian: Narhval

English: Narwhal

Danish: Narhval

The English name “narwhal” is derived from the Old Norse word ‘nar’ which means ‘corpse’, perhaps in reference to the animal’s grey colour, thought to resemble that of a drowned sailor (Heide-Jørgensen and Laidre 2006).

Size

Adult male narwhals reach lengths of up to 460 cm and weights of 1,645 kg, while females are smaller at up to 400 cm and 1,200 kg. The tusk of a male narwhal can exceed 2 m in length.

Productivity

On average, female narwhals have one calf every 3 years. They reach sexual maturity between 7 and 9 years of age.

Migration

Narwhals spend their entire lives in cold Arctic waters. They are periodically associated with sea ice but they are primarily found in open-water coastal areas in summer.

Feeding

Narwhals feed primarily on fish and squid, particularly polar cod (Boreogadus saida), Arctic cod (Arctogadus glacialis), Greenland halibut (Reinhardtius hippoglossoides) and squid of the genus Gonatus.

Lifespan

Narwhals can live for more than 100 years.

General Characteristics

The narwhal is a medium-sized toothed whale that belongs to the family Monodontidae. The only other member of this family is the beluga.

Narwhals have stout, torpedo-shaped bodies with a low dorsal ridge in place of a dorsal fin and a concave-shaped tail fin. They lack the extremely flexible neck and well-defined beak of their closest relative, the beluga. Like the beluga, the narwhal has short paddle-shaped front flippers.

At birth, narwhals are grey to greyish-blue in colour. They become darker and more mottled as they grow older, with white patches developing from their abdomen to up over their backs. Adult narwhals are usually light grey in colour, with a mottled pattern of darker markings over a lighter background. Very old narwhals become almost completely white.

Male narwhals develop a tusk, which is a modified canine tooth that grows out the left side of the jaw, twisting anti-clockwise to form a spiral. Occasionally male narwhals have two tusks and a small percentage of females also have a tusk.

LIFE HISTORY

The narwhal is a medium-sized toothed whale, with males reaching a maximum length of about 460 cm and a maximum weight of 1,645 kg, with females slightly smaller at 400 cm and 1,200 kg (NAMMCO 2013, Garde et al. 2007, 2021). Narwhals are very long-lived animals. Recent research looking at chemical changes in the eye lens has demonstrated that narwhals can live for more than 100 years (Garde et al. 2007). This makes the narwhal the longest-lived of the toothed whales and one of the longest-lived of all mammals.

The narwhal reaches sexual maturity between the ages of 7 and 9. They mate from late May to early June and calves are born about a year later, during the time the animals are migrating towards their summering areas (Heide-Jørgensen and Garde 2010). On average, narwhals have a single calf every 3 years throughout their lifetime (NAMMCO 2013, Garde et al. 2007, 2021).

The Unicorn of the sea

The most distinguishing feature of the narwhal is the male’s long tusk, which has led them to be called the “unicorn of the sea”. The tusk is actually a modified canine tooth. Usually only one tusk erupts from the left side of the upper jaw, but a small percentage of male narwhals have a tusk on both sides of the jaw. Other than the single tusk, narwhals are toothless. The tusk is spiral in form, almost always in an anti-clockwise direction. In some narwhals the tusk may exceed 2 m in length (NAMMCO 2013, Garde et al. 2007).

Double Narwhal © Zoologisches Museum Hamburg

FEEDING

Narwhals feed primarily on fish and squid throughout their range. Both the diet and the intensity of feeding vary seasonally.

During the summer, narwhals apparently feed little; hence the stomachs of narwhals harvested at this time of year are often empty (Garde et al. 2021). They begin to feed more heavily in the autumn during migration and especially during the winter at their deep-water wintering grounds. In Baffin Bay, the winter diet is dominated by the Greenland halibut (Reinhardtius hippoglossoides) (Laidre and Heide-Jørgensen 2005b). To access this bottom-dwelling species, narwhals must make repeated dives to depths of between 800 and 1,600 m. Each dive takes up to 25 minutes, with about half of that spent near the bottom (Laidre et al. 2003, 2004).

Arctic cod (Arctogadus glacialis), polar cod (Boreogadus saida), and squid of the genus Gonatus also form an important part of the winter diet. These species may be available in mid-water in areas too deep for narwhals to reach the bottom (Laidre et al. 2003, 2004, Laidre and Heide-Jørgensen 2005b). During the spring, as narwhals follow the retreating ice edge, polar and Arctic cod become more important in the diet (Laidre et al. 2004). Recently, capelin (Mallotus villosus) have also been found in narwhal stomachs during summer in East Greenland (Garde et al. 2021). Plasticity in feeding ecology suggests that narwhals are able to change their foraging ecology in response to changing environments (Dietz et al. 2021, Watt et al. 2013, 2015, Watt and Ferguson 2015).

Locating prey

Like all toothed whales, narwhals use echolocation to find prey (Blackwell et al. 2018). This is particularly important for a species that does most of its feeding in very deep waters during the long nights of the Arctic winter. A recent study in which a camera was attached to free ranging narwhals demonstrated that narwhals spend a high proportion of their time upside down while diving and swimming at the sea bottom (Dietz et al. 2007). This may allow them to better project their echolocation clicks to locate prey, and perhaps also to protect their lower jaw and tusk from contact with the bottom.

Importance as predators

There have been some attempts to determine the importance of narwhals as predators by modelling how much fish they consume. Laidre et al. (2004) used a bioenergetic model to estimate the biomass of Greenland halibut needed to sustain narwhals during the five months that they spend at their wintering grounds. Estimates were made for varying levels of Greenland halibut in the narwhal diet: 25%, 50% and 75%. Assuming a diet comprised of 50% Greenland halibut, the 32,000 narwhals in the southern overwintering area would eat approximately 576 tonnes per day, or about 86,000 tonnes of Greenland Halibut for the five-month winter period (DFO 2014). The area classified as the northern over-wintering ground supports a larger number of whales (approx. 45,000) and was estimated to require 700 tonnes per day with a mean consumption over five months of 110,700 tonnes (95% CI of 53,000 – 310,300 t) (DFO 2014, DFO 2007). This amount is, however, larger than the estimated biomass of Greenland halibut in that area, suggesting that narwhals in this area make greater use of other prey species.

DIMORPHISM

Narwhals show sexual dimorphism, with several differences between males and females. Adult male narwhals are on average longer and heavier than females, reaching a maximum length of about 460 cm and a maximum weight of 1,645 kg. Adult females have a maximum length of 400 cm and weight of 900 kg (NAMMCO 2013, Garde et al. 2007).

The other obvious difference between the sexes is the presence of the tusk in males. While a small percentage of females may also have a tusk (roughly 6% of tusked narwhals in the Canadian Inuit harvest were females (Petersen et al. 2012)), it is a feature found in all adult males. The tusk is actually a modified canine tooth, and is in fact the only tooth these whales possess. Usually, only one tusk erupts from the left side of the upper jaw, but in a small percentage of male narwhals a second tusk erupts from the right side of the jaw. The tusk is spiral, almost always in an anti-clockwise direction (NAMMCO 2013, Garde et al. 2007).

Narwhal tusks protruding out of the water. © Mads Peter Heide-Jørgensen

PREDATION AND OTHER NATURAL THREATS TO THE POPULATION

Apart from man, the main predators of the narwhal are the killer whale and the polar bear. Narwhals react to the presence of killer whales by moving close to land or sea ice, and forming tight groups. They may move into very shallow water and even occasionally become beached (Laidre et al. 2006). Current reductions in sea ice and increases in Arctic killer whale sightings in the Canadian Arctic could potentially affect movement and behaviour of narwhals (Breed et al. 2017).

Because of their association with heavy ice cover, narwhals are vulnerable to becoming trapped in ice if high winds move ice around or the temperature drops suddenly. Narwhals require leads or open areas in the ice to breathe, since they are unable to open or maintain a breathing hole through thick ice. A cetacean entrapment in ice is called a savsaat in Inuktitut, and is a relatively common if unpredictable occurrence. Such entrapments may be a major source of natural mortality for narwhals (Heide-Jørgensen et al. 2002). Many of these events probably go undetected, especially if they are small and in a remote location.

A savsaat in 2008 in Eclipse Sound saw more than 600 narwhals entrapped. 629 narwhals were harvested from the savsaat, but more animals may have drowned (DFO 2008). Such a large entrapment of animals is rare in Nunavut, having been recorded only once before in the previous century (Heide-Jørgensen et al. 2002).

Polar bears in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago will attack narwhals from the ice edge or when the whales are in shallow water.

Distribution and Habitat

The narwhal is one of three species of whales (along with beluga and bowhead whales) that spend their entire lives in cold Arctic waters.

During the autumn, winter and early spring, the narwhal lives in dense pack ice, using leads and polynyas (open water areas within pack ice) to breathe. In the spring, narwhals follow the receding pack ice and spend the summer usually in shallower, ice-free waters closer to land, often within fjords or close to glacier fronts.

SEASONAL MIGRATION

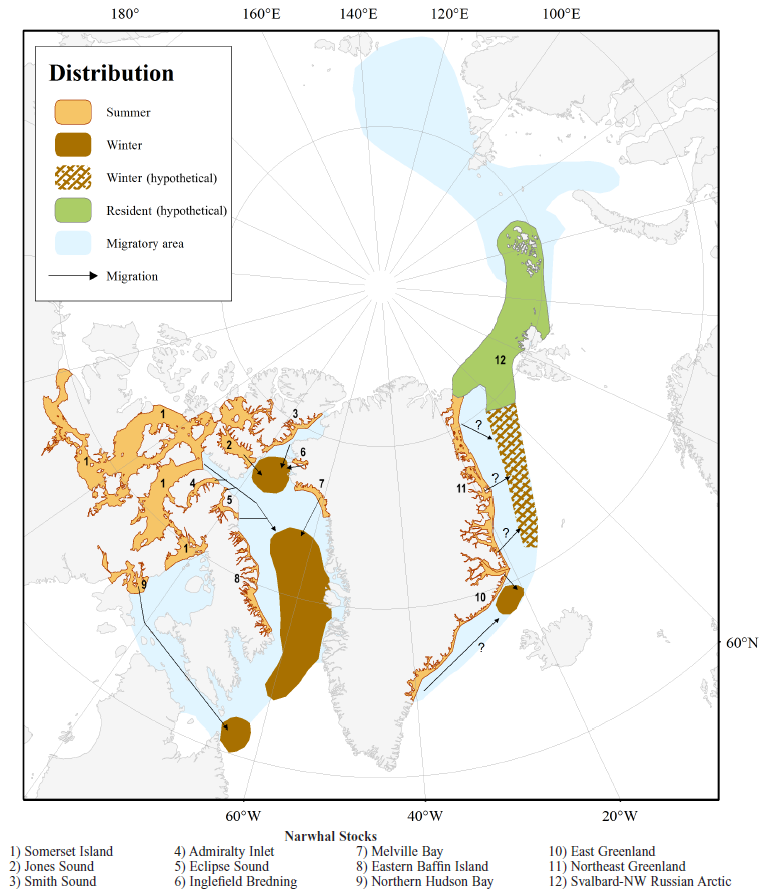

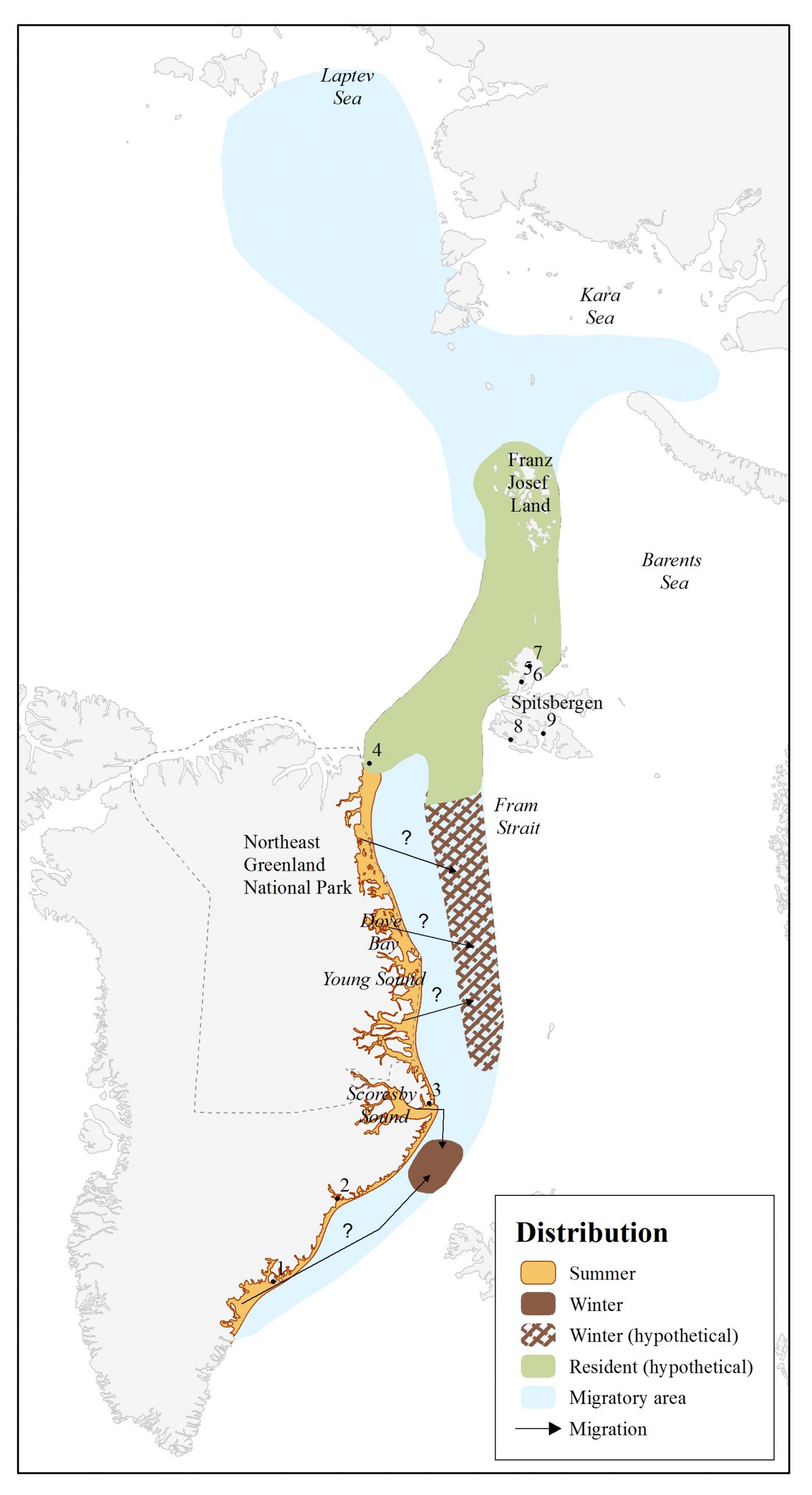

Narwhal distribution and migration as recognised by the Global Review of Monodontids (Hobbs et al. 2019)

Much has been learned about the physical and seasonal habitat of narwhals through the application of satellite-linked tags. In such studies, narwhals are captured in nets and the tags are attached either to the tusk (in male narwhals) or by bolts through the dorsal ridge. The tags transmit data when the narwhal surfaces. Along with location, tags can collect data on diving and the time spent at specific depth intervals. To date, tagging studies have been conducted on almost all summer aggregations of narwhals in Canada and Greenland (Heide-Jørgensen et al. 2013b) and in Svalbard (Lydersen et al. 2007). Read more in Section 11: Research in NAMMCO member countries.

Spring

Narwhals begin migrating as early as late March or early April, following the receding pack ice into areas inaccessible in the winter. At this time of year they can be found at ice edges in the Canadian Eastern Arctic, West and East Greenland and Svalbard. Narwhals tend to spend more time near the surface and travel farther each day during the spring (Laidre et al. 2004).

Summer

During the summer, narwhals can be found closer to land and in shallower water than at other times of the year (Laidre et al. 2004, Heide-Jørgensen et al. 2013ab). They move into areas of the Canadian Eastern Arctic, West and East Greenland and Svalbard that are covered by landfast ice and therefore inaccessible at other times of the year. During this period, narwhals often congregate in fjords and at glacier fronts. They also form larger groups than during other periods, up to several hundred animals.

Autumn

Their return to wintering areas begins in late September or later, depending on when the sea ice begins to form. Autumn movements are often quite rapid, although narwhals may occupy other coastal areas that remain ice-free for periods at this time of year (Heide-Jørgensen et al. 2013ab). They reach their wintering grounds by November or early December.

Winter

In winter, narwhals are usually found offshore in areas with mobile pack-ice, often over deep water where they can target deep-water prey like Greenland halibut (Heide-Jørgensen et al. 2002, Kenyon et al. 2018, Laidre and Heide-Jørgensen 2011).

Habitat

Sea ice with open water leads in Labrador, Canada. © Wikipedia

During the winter, narwhals occupy areas covered with heavy pack ice over water up to 2,000 m in depth. In Baffin Bay they spend the winter in areas with as little as 0.5% open water (Laidre and Heide-Jørgensen 2005a), diving repeatedly to depths down to 1,600 m to feed on fish at or near the sea bottom. Narwhals are physiologically adapted for long dives, having a very high ratio of slow oxidative to fast twitch muscle fibres, and by having the highest levels of myoglobin recorded in any marine mammal, giving them exceptional oxygen storage capacity (Williams et al. 2011). They can dive aerobically for up to 24 minutes, giving them the ability to feed at great depths and move up to 1.4 km between breathing holes.

DEFINING STOCKS

A “stock” of animals is a term often used in wildlife management. The stock is the basic unit of management, mainly because it describes a group of animals that is reproductively and often physically isolated from other groups. Animals in a stock generally share similar life history characteristics, such as age of sexual maturity, rate of breeding etc. Most importantly, animals within a stock mate and breed primarily with other members of that stock.

It is important to try to determine whether narwhals are all members of one stock, or if there are different stocks, for a number of reasons. Narwhals are hunted throughout Nunavut in Canada and in Greenland. In order to set appropriate harvest levels, managers need to know if narwhals are being taken from one or more stocks, and which stocks those are. It is also important to know if there are different stocks in order to make sound population estimates.

Stock identity is determined in various ways: through analysing the genetic makeup of individuals, tagging studies, studies of stable isotope ratios, use of traditional ecological knowledge, and studies of morphology.

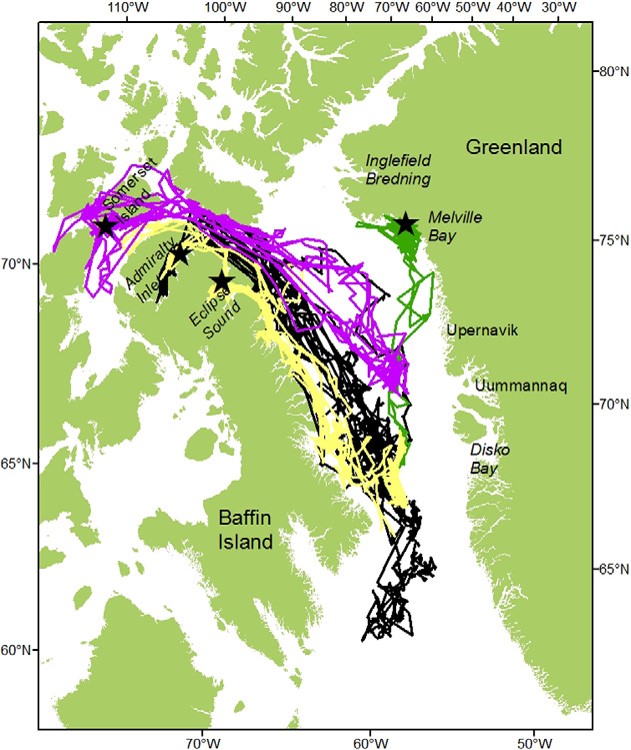

Tracklines of narwhals tagged at various summering locations (stars) to their wintering area in Baffin Bay and Davis Strait. From Heide-Jørgensen et al. (2012).

Genetic studies, stable isotope analysis, and morphology

In general, narwhals appear to have low genetic diversity and there is little differentiation among stocks (NAMMCO 2013). There are two possible reasons for this: either a “bottleneck”, or population restriction, occurred at some point in the distant past, or there is currently a high rate of gene flow between areas. Either or both explanations could be correct.

Despite this overall low genetic diversity, genetic studies have found that narwhals in East Greenland are distinct from those in West Greenland (NAMMCO 2013). Within West Greenland, far northern (Uummannaaq) narwhals are different from those found further south. Differences are also seen between Baffin Bay, Northern Hudson Bay, and East Greenland populations (Petersen et al. 2011, NAMMCO 2013). Less distinct differences have also been found between narwhals that summer in Jones Sound and the Somerset Island area (Petersen et al. 2011). A more recent genetic study of East Greenland aggregations (NAMMCO 2023) confirmed indications from local hunters, morphological, behavioural, and survey data, that the animals supplying the spring hunt in Scoresby Sound are distinct from those hunted in the summer in that area. Indeed, the “spring” animals are more closely related to animals from Northeast Greenland and Svalbard, while the “summer” animals are linked to aggregations further south. Animals from around Sermilik and Kuummiut are likely also genetically distinct from the more northern aggregations.

Similar results have been found using stable isotope analysis of carbon and nitrogen from skin samples. In this analysis, a clear difference was seen between northern Hudson Bay, East Greenland, and all other stocks (Watt et al. 2012b).

East Greenland narwhals are also distinct from the other populations in their cranial (the part of the skull that encloses the brain) morphology (Wiig et al. 2012a). However, no differences in cranial morphology were seen between West Greenland and Canadian narwhals.

Contaminant level analysis

Another method that has been used to try to identify stocks is analysis of organochlorine (OC) contaminant levels in narwhal tissues. Differences in contaminant levels can be caused by differences in feeding, which may depend on prey selection, feeding patterns in summering/wintering areas or on migration routes, and in the feeding behaviour of the individual. In a 2003 study using this approach, narwhals sampled from Repulse Bay could be distinguished from all other narwhals studied (de Marche and Stern 2003). More recently, Pedersen et al. (2024) found significant differences in contaminant loads between East Greenland narwhals and those from other regions, further supporting the use of contaminant markers as evidence of stock separation.

Tagging studies

Tagging studies have been conducted in a number of locations throughout the narwhal’s range. These studies suggest interannual site fidelity, which means that narwhals generally return to the same summering and wintering areas year after year. There are, however, exceptions to this rule. One narwhal tagged in Admiralty Inlet wintered in Northern Foxe basin rather than Davis Strait (Watt et al. 2012a, NAMMCO 2013), and another tagged in northern Greenland migrated to Somerset Island in the summer (Heide-Jørgensen et al. 2013).

Mating

Most narwhal stocks from northern Canada and West Greenland mix in the winter in Baffin Bay/ Davis Strait (Heide-Jørgensen et al. 2013). Mating, however, occurs during the spring migrations to the summering areas, which maintains summer stock identity (Heide-Jørgensen and Garde 2011, NAMMCO 2013).

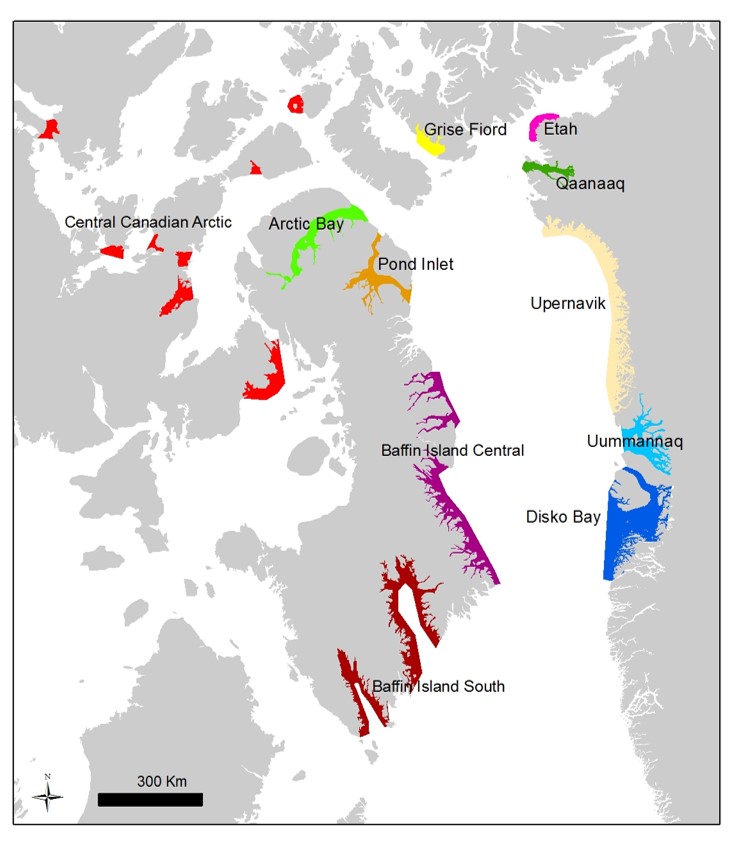

SUMMER AGGREGATIONS

The “summering aggregations” (areas where narwhals are found in the summer) currently provide the basis for the determination of management areas. This is primarily because: 1) narwhal stocks tend to be geographically isolated during the summer, and 2) because it is during the summer and at these locations that narwhals are usually hunted. The Global Review on Monodontids (NAMMCO 2018, Hobbs et al. 2019) recognised seven stocks in Canada, two in West Greenland, two in East Greenland and one in Svalbard–Northwest Russia (NAMMCO 2018). Since then, the Ad hoc Working Group on Narwhal in East Greenland (NEGWG) has further distinguished two stocks in the area around Ittoqqortoormiit/Scoresby Sound at different times of the year (NAMMCO 2023). Recent findings now support the recognition of a summering population in Nares Strait as an additional stock. This group appears to be geographically and potentially genetically distinct, with implications for future management (Heide-Jørgensen et al., 2024).

Geographically, East Greenland is divided into three management areas to support a precautionary approach (see below for more information), with the NEGWG recommending that the animals supplying the “spring” hunt of narwhals in Scoresby Sound be managed separately from the “summer” animals.

Narwhal distribution around East Greenland, Svalbard and Northern Russia as recognised by the Global Review of Monodontids (Hobbs et al. 2019).

Svalbard and Northwest Russian Arctic

There is very little information on the narwhals that inhabit this area. Generally, narwhals were historically sighted and sometimes caught by Norwegian sealers and whalers in the area between East Greenland, Svalbard, the New Siberian Islands and Novaya Zemlya (Gjertz 1991, Lydersen et al. 2007). Narwhals are most frequently observed in the northwest and northeast parts of the Svalbard archipelago, but this probably reflects the numbers of observers rather than the number of animals. The abundance in part of their distribution north of Svalbard was estimated at 837 (CV=0.50) in 2015 (Vacquié-Garcia et al. 2017). Generally, narwhals in this area appear to be widely dispersed and do not form large predictable aggregations as they do in other areas. The wintering area of Northeast Atlantic narwhals is not known, but it is likely that they overwinter within the extensive pack ice in this area. Farther east, sightings of narwhals are very rare or non-existent.

East Greenland

During the summer, narwhals are found along the East Greenland coast with concentrations found in the areas around Scoresby Sound, Tasiilaq, and Kangerlussuaq (Heide-Jørgensen et al. 2010, NAMMCO 2017). Narwhals have a scattered distribution along the coast and periodically occupy many fjords in the area. The NAMMCO-JCNB Joint Working Group (see “Management”), the NAMMCO Scientific Committee, and the NAMMCO Management Committee for Cetaceans agreed to recognise three separate “management units” in East Greenland in order to adopt a precautionary approach to providing management advice and minimise the potential for local depletions. The three management areas currently recognised for narwhals in East Greenland are: Tasiilaq (south of 67°N), Kangerlussuaq (68°30’N to 67°N), and Ittoqqortoormiit (Scoresby Sound and Blosseville Coast south to 68°30’N). In 2023, the NEGWG agreed that a fourth management unit should be included, specifically for the animals supplying the spring hunt in the Ittoqqortoormiit area.

Northeast Greenland

Narwhals are frequently found north of Scoresby Sound and as far north as Nordøst Rundingen – 82°N (Boertmann and Nielsen 2009 and 2010). Given the long coastline, it is possible that there are several stocks in Northeast Greenland. However, there is currently very little available data to determine stock structure with confidence (NAMMCO 2018). Narwhals may also occur between Greenland and Svalbard but there is little supporting data for this, despite recent genetic evidence indicating that the Northeast Greenland and Svalbard stocks are related (NAMMCO 2023).

West Greenland (Inglefield Bredning and Melville Bay stocks)

Narwhals are found off West Greenland at all times of the year. Two stocks occur in summer aggregations at Inglefield Bredning and Melville Bay. During the autumn, winter and spring they are found in the ice pack off the West Greenland coast from Smith Sound to just south of Disko Bay (Heide-Jørgensen et al. 2010). While the summering aggregations are considered to be stocks for management purposes, at other times of the year, narwhals off West Greenland are likely composed of a mixture of animals from several summering areas, including stocks that summer in Canada (Heide-Jørgensen et al. 2012).

Canadian Stocks

Distribution and locations associated with narwhal stocks of eastern Canada and West Greenland: (1) Somerset Island (2) Eclipse Sound (3) Admiralty Inlet (4) Jones Sound (6) Inglefield Bredning (7) Prince Regent Inlet (8) Peel Sound (9) Barrow Strait (10) Cambridge Bay (11) Gjoa Haven (12) Hall Beach (13) Igloolik (14) Baffinland-Mary River (15) Kugaaruk (16) Resolute (17) Creswell Bay (18) Taloyoak (19) Pond Inlet (20) Arctic Bay (21) Nanisivik (22) Grise Fiord (23) Cape D’Urville (24) Lancaster Sound (25) Clyde River (26) Qikitarjuak (27) Cape Dorset (28) Coral Harbour (29) Chesterfield Inlet (30) Baker Lake (31) Rankin Inlet (32) Repulse Bay (33) Whale Cove (34) Arviat (35) Kimmirut (36) Renselaer Bay (37) Qaanaaq (38) Siorapaluk (39) Qeqertat (40) Upernavik (41) Uummannaq (Hobbs et al. 2019).

There are seven stocks/summer aggregations of narwhals in Canada.

The North Hudson Bay narwhals summer in northwestern Hudson Bay, particularly near Repulse Bay and into Foxe Basin. Tagging studies indicate that this group winters in the pack ice at the eastern end of Hudson Strait (DFO 2010a, Heide-Jørgensen et al. 2012). The Northern Hudson Bay stock can be separated from other Canadian stocks through genetics, contaminant analysis and by the fact that its distribution does not overlap with that of any other group of narwhal.

The six other Canadian stocks (Somerset Island, Jones Sound, Smith Sound, Eclipse Sound, Admiralty Inlet, and East Baffin Island) winter in southern Baffin Bay/northern Davis Strait and have summer concentrations throughout the eastern Canadian Arctic Archipelago. These stocks are considered “shared stocks” with Greenland, as they migrate into Greenlandic waters seasonally. Tagging studies have indicated that there is little mixing between areas during the summer, although it does sometimes occur.

The distribution of all these stocks, and the two stocks in West Greenland, overlaps in the winter and, unsurprisingly, they cannot be readily differentiated genetically or by other means. Nevertheless, these divisions are useful for management purposes as it allows a stock allocation to hunting areas, which is a more conservative and precautionary approach than assuming that there is only one “panmictic” stock of narwhals in the area. This is because the latter approach could result in local depletions if an underlying stock structure did exist.

ESTIMATING ABUNDANCE

Estimating the abundance of narwhals is difficult due to the remoteness and large size of their distribution area, the mobility of the animals, and their close association with sea ice. Aerial surveys are most commonly used. However, the results must be corrected for both whales that are at the surface but missed by observers, and those that are below the surface/out of sight when the survey airplane is overhead. Another problem is that direct comparisons between surveys are not always possible, since surveys rarely have the same timing or cover the same area.

A rough estimate for the total world population is 85,000 – 100,000 animals (White 2012, NAMMCO 2017). A more detailed breakdown of the population status in different areas of the Arctic is given below.

Svalbard-Northwest Russian Arctic

There has not yet been a survey around Svalbard specifically targeting narwhals. However, a multi-species survey in the marginal ice zone north of Svalbard in August 2015 resulted in an estimate of 837 narwhals (CV = 0.50) (Vacquié-Garcia et al. 2017). This is likely a minimum estimate as the survey did not cover all of the area where narwhals may occur. There are no previous abundance estimates to compare with this 2015 estimate, so it is not possible to say anything about trends for this stock.

Information on narwhal sightings in the northwestern Russian Arctic (Barents and Kara Seas) comes mostly from the annual National Park “Russian Arctic” monitoring program, as well as opportunistic observations during oil/gas geological explorations, scientific expeditions, and tourist cruises. There is no abundance estimate for narwhals in this region.

East Greenland

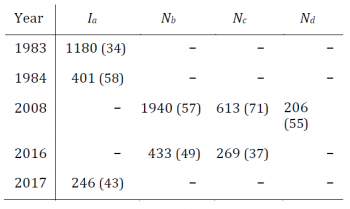

The East Greenland stock of narwhals occurs along the coast from about 64°N to 72°N and is divided into the three management areas of Scoresby Sound/Ittoqqortoormiit, Kangerlussuaq and Tasiilaq (see section on North Atlantic Stocks). Aerial surveys have been conducted around the hunting grounds in Scoresby Sound in 1983-84 and 2017, and from Tasiilaq to Scoresby Sound in 2008 and 2016. The NAMMCO Ad Hoc Working Group on Narwhal in East Greenland reviewed data from all of these surveys and applied correction factors for perception and availability bias to the abundance estimates, including retrospectively to the initial estimates from the 1983 and 1984 surveys (Larsen et al. 1994). The corrected abundance estimates from all currently available surveys in East Greenland are presented in the table below.

Abundance estimates with CV in brackets (given in %). Ia is relative estimates covering only Scoresby Sound. Nb is an absolute estimate for Scoresby Sound and the Blosseville Coast. Nc is an absolute estimate for Kangerlussuaq. Nd is an absolute estimate for Tasiilaq (NAMMCO 2019).

A recent study by Hansen et al. (2024) applied a Hidden Markov Line Transect Model to improve abundance estimates and revealed a marked decline in both abundance and distribution of narwhals in Southeast Greenland between 2008 and 2017. While group sizes remained stable, sightings became more clustered, and narwhals were no longer found in the southernmost areas where they were previously observed in 2008. These findings highlight a worrying contraction in summer habitat use, likely due to environmental changes and other pressures.

Northeast Greenland

The area north of Scoresby Sound is a National Park. It is the largest protected area in the world and includes protection of the sea up to 3 nautical miles from the shoreline. Northeast Greenland is therefore not part of the hunting grounds for narwhals, although narwhals from this area may be supplying the hunt in regions further south. The Northeast Water polynya can be an important habitat in winter. There is, however, little documentation of the population abundance and distribution in this area. A dedicated aerial survey was conducted in Northeast Greenland (covering the Northeast Water polynya) in March/April 2017. Narwhals were detected twice during this survey and no abundance estimation was made on this low sighting rate.

However, Hansen et al. (2024) provided the first robust estimates for Dove Bay and the Greenland Sea based on summer surveys. In Dove Bay, fully corrected abundance was estimated at 2,297 (CV= 0.30) individuals in 2017 and 1,395 (CV=0.33) individuals in 2018. The difference was likely due to a late ice breakup in 2018, which may have caused narwhals to move to other fjord systems nearby. In the Greenland Sea, the same study estimated 2,908 (CV= 0.30) narwhals in 2017 based on sightings from the coastal area north of Dove Bay. These results represent the first quantitative population assessments for these areas and significantly improve our understanding of narwhal distribution in Northeast Greenland.

Aerial surveys were conducted over the eastern part of the North Water polynya in April 2014. The resulting estimates suggested that 3,059 narwhals (95 % CI: 1,760–5,316) wintered in the eastern part of the North Water polynya during this time (Heide-Jørgensen et al. 2016). Narwhal sightings were also recorded during a 2018 multi-species survey of the North Water, with 23 narwhal sightings recorded.

Inglefield Bredning

Migration patterns for this stock are unknown but a portion of the whales that winter in the North Water polynya could be the same narwhals that summer in Inglefield Bredning (see abundance estimate above).

The most recent abundance estimate for the Inglefield Bredning stock is from 2019, with a fully corrected estimate of 2,874 animals (CV=0.28) (Hansen et al., 2024; NAMMCO-JCNB, 2022). The last survey before that was in 2007, resulting in an abundance estimate of 4,109 (CV=0.29) (Heide-Jørgensen et al., 2010; NAMMCO-JCNB, 2022). Surveys conducted in 1985–1986 and 2001–2002 have used different methods and covered different areas, so the abundance estimates are not directly comparable to allow for determination of trends (Born et al. 1994; Heide-Jørgensen 2004). The estimates from 2007 and 2019 suggest a decrease in abundance, but this is not significantly different from zero (Hansen et al., 2024). The distribution seen in between 2007 and 2019 was, however, similar to past surveys (Heide-Jørgensen et al. 2010).

Melville Bay

Melville Bay was last surveyed in 2019 and the fully corrected estimate was 4,755 animals (CV=0.77) (Hansen et al., 2024). Previous surveys resulted in abundance estimates of 1,834 (CV=0.92, 95% CI: 396–8,500) in 2007, 915 (CV=0.44, 95% CI: 431–2,141) in 2012, and 1,768 (CV=0.39, 95% CI: 864–3,709) in 2014. Although there is a suggestion of increase in abundance since 2012, this trend is not significantly different from zero. Additionally, the distribution of sightings has remarkably changed. Where in 2007 narwhals were detected in all four surveyed strata, in 2012 narwhals were sighted in 3 out of 4 strata, in 2014 in 2 out of 4 strata, and in 2019 only in the central stratum. This decline in area usage in the coastal part of Melville Bay could be an indication of a decline in the population (Hansen et al., 2024).

The wintering area in eastern Baffin Bay along the West Greenland coast was most recently surveyed in March–April 2012, as part of a long-term series of surveys conducted 7 times since 1981. The survey resulted in a corrected estimate of 18,583 narwhals (95% CI: 7,308–47,254). Aggregations of narwhals were seen clumping at the sea ice edge, probably due to bathymetric features in this area. Numbers here seem to fluctuate from year to year, probably because of annual variations in ice conditions in the area, as well as variations in the timing of seasonal migrations. This result is a large increase in the abundance from the previous survey in 2006, which was 7,819 narwhals. This is likely because the 2012 survey covered a larger survey area, especially in the north part of the area where 1/3 of all the animals were seen. This area had not been previously surveyed.

Canadian Stocks

A comprehensive survey with narwhals as the main target species was carried out in Canadian waters in August 2013 and abundance estimates for most stocks have been developed from this survey. The survey covered all major known summer aggregation areas for Baffin Bay narwhals in Canada, including Peel Sound, Prince Regent Inlet, Admiralty Inlet, Eclipse Sound and the East Baffin Coast. Jones Sound and Smith Sound were surveyed for the first time. This was the largest aerial survey ever carried out in Canada, with three planes and 15 observers taking part over a four-week period. It is also the first time that all major narwhal habitat has been surveyed in a single year.

Somerset Island

The most recent abundance estimate for this stock is from the 2013 survey and was 51,730 (CV=0.28), which has been corrected for perception and availability bias (Doniol-Valcroze et al., 2015; NAMMCO-JCNB, 2022). This stock has been surveyed in 1981, 1984, 1996, 2002–2004 and 2013, with variable coverage. Based on the data available from the last 30 years, the stock appears to be increasing (NAMMCO 2015, Witting 2016).

Jones Sound

The 2013 survey was the only time this stock has been surveyed and resulted in an abundance estimate of 13,200 (CV=0.38) narwhals, corrected for perception and availability bias (Doniol-Valcroze et al., 2015; NAMMCO-JCNB, 2022). Since this is the only survey that has been conducted, it is not possible to determine a trend for this stock.

Smith Sound

The survey conducted in 2013 resulted in an abundance estimate for the Smith Sound stock of 17,010 (CV=0.68) narwhals, corrected for perception and availability bias (Doniol-Valcroze et al. 2015, NAMMCO-JCNB, 2022). This is the only survey that has been conducted of this area and there is therefore not enough information to determine a trend.

Eclipse Sound

The most recent survey in Eclipse Sound was conducted in 2019 and resulted in an abundance estimate of 8,460 animals (CV=0.32), corrected for perception and availability bias (Golder, 2020; NAMMCO-JCNB, 2022). This stock was previously surveyed in 2004 (21,110; CV=0.41), 2013 (21,110; CV=0.31), and 2016 (12,040; CV=0.30) (Doniol-Valcroze et al. 2015). There is concern about a possible decline in abundance in Eclipse Sound.

Admiralty Inlet

The most recent survey in Admiralty Inlet was conducted in 2019 and resulted in an abundance estimate of 25,260 animals (CV=0.25), corrected for perception and availability bias (Golder, 2020; NAMMCO-JCNB, 2022). The previous survey in 2013 estimated an abundance of 36,430 (CV=0.47) (Doniol-Valcroze et al., 2015; NAMMCO-JCNB, 2022). Six surveys of this stock have been conducted since 1975 and indicate no significant change in abundance (Richard et al., 2010; Asselin and Richard, 2011; Witting, 2016).

Eastern Baffin Island

The most recent abundance estimate for this stock is based on the 2013 survey and estimates 11,990 (CV=0.40) animals. A previous survey in 2003 resulted in an abundance estimate of 10,710 (CV=0.34). Both of these estimates have been adjusted for availability and perception bias (Doniol-Valcroze et al., 2015; NAMMCO-JCNB, 2022). It is not possible to determine a trend from these two estimates.

North Hudson Bay

This stock has been surveyed in the early 1980s, 2000 and 2011 using different scales, methods and procedures. The most recent survey from 2011 resulted in an estimate of 12,485 narwhals (95% CI: 7,515 – 20,743) (Asselin et al. 2011). However, to provide comparability of estimates from across the different surveys, the 2011 data were re-analysed using the methods of the visual surveys in 1982 and 2000. This yielded surface estimates of 1737 (95% CI: 1002 – 3011) in 1982, 1945 (95% CI: 1089 – 3471) in 2000, and 4452 (95% CI: 2707 – 7322) narwhals in 2011 (Asselin et al. 2012).

Svalbard – Northwest Russian Arctic

There is currently very little information about narwhal abundance, distribution, and stock identity in this area, and therefore it is difficult to assess the status of the stock. The experts at the Global Review of Monodontids (GROM) meeting held in 2017 (NAMMCO 2018, see box to the right) gave a moderate level of concern for narwhals in this area, mainly due to the lack of information available and the likelihood that there is a low abundance. Narwhals are protected in Svalbard and Russia.

East Greenland

In 2017, the NAMMCO-JCNB Joint Working Group and the Global Review of Monodontids (GROM), both recognised that the environment in this area is changing rapidly, including increased sea surface temperatures, rapidly retreating ice cover, and disappearance of tidewater glaciers. These changes are resulting in poor and reduced narwhal habitat. In addition, boreal species (including humpback whales) have been observed in the area, which is likely causing competition for prey, exposure to novel diseases, etc. It is difficult to tease apart the impacts of these environmental changes from the hunting pressure in the area.

Given the concerns about a changing habitat for narwhals in East Greenland, the GROM (NAMMCO 2018) stated “There is a high level of concern for narwhals in East Greenland due to the lack of data (particularly on stock structure), low abundance, declining trend, likely overharvest, and the numerous climate-related changes in habitat.” In 2019, NAMMCO convened an Ad Hoc Working Group on Narwhal in East Greenland (NEGWG) to review and assess the status of the stock and provide advice on the future sustainability of catches for all three management areas (NAMMCO 2019a). The NEGWG has met twice more since then, in 2021 and 2023. At its latest meeting, the Working Group conducted stock assessments based on recent genetic findings and abundance estimates from the three management areas in East Greenland.

In management area 1—Ittoqqortoormiit, Scoresby Sound, and Blosseville Coast south to 68°30’N—the population assessment model estimated a small and depleted summer aggregation (down to only 11% of the historical population estimate of 1,570 animals in 1955). The 2022 abundance estimate is approximately half of the last absolute estimate from 2016, and one third (i.e., 71 individuals) of the 2022 point estimate (214 narwhals) was removed by the hunt in 2022 and 2023. With an assessment estimate of 173 (90% CI:67–314) narwhals remaining in 2024, if annual catches continue at the 2024 quota-level, there is 90% risk that the stock will become near extirpated by 2030 (falling below 100 individuals) (NAMMCO 2023).

In management area 2—Kangerlussuaq 68°30’N to 67°N—the population assessment model estimated a small, depleted aggregation (down to 12% of the historical population estimate of approximately 1,150 narwhals in 1955) in 2024, namely, 138 (90% CI:72–231) individuals remaining. The model estimated a 90% risk of near extirpation by 2030 if annual catches continue at the 2024 quota-level, a risk that is reduced to 15% if no narwhals are taken (NAMMCO 2023).

In management area 3—Tasiilaq, south of 67°N—the population model estimated a near extirpated stock of only 3 (90% CI:0–65) individuals remaining in 2024. This follows an almost continuous decline from 769 narwhals in 1955, with the two latest surveys of the area, in 2016 and 2022, resulting in abundance estimates of zero animals. The population model estimated a 91% risk that the stock will be extirpated by 2030 if annual catches continue at the 2024 quota-level (NAMMCO 2023).

The continued hunting of these small and depleted stocks, combined with observed impacts from climate change, and possible disturbance from other anthropogenic stressors such as noise, lead to both the NEGWG (NAMMCO 2023) and the NAMMCO Scientific Committee (NAMMCO 2024a) repeatedly expressing significant concern over the status of these stocks. As a result, in 2024, the NAMMCO Management Committee forwarded a recommendation urging Greenland to implement a management approach aiming at zero quotas, to ensure the long-term sustainability of these stocks (NAMMCO 2024b).

Reviewing the status of all belugas and narwhals

© M.P. Heide-Jørgensen

In March 2017, NAMMCO organised a Global Review of Monodontids (GROM), which discussed the conservation status, threats, and data gaps for all stocks of belugas and narwhals globally. The previous review had been performed almost 20 years ago and a large amount of new information had become available since then, especially on stock identity, movements, abundance, and threats to the populations. Additionally, many new stressors have emerged in the last 20 years, especially related to climate change.

Stock experts representing Greenland, Canada, Alaska, Russia, the Government of Nunavut, Nunavut Tunngavik, Inc., the Inuvialuit Settlement Area, and the Nunavik Wildlife Management Board participated in the review.

The report can be found here and the Global Review of Monodontid Stocks was published in 2019 (Hobbs et al., 2019).

NORTHEAST GREENLAND

Narwhals are frequently sighted along the coast north of Scoresby Sound. This area is within the Northeast Greenland National Park (the largest protected area in the world) and no hunting takes place in marine waters along the Park’s boundary. Despite the protection of narwhals in this area, there is moderate concern for this stock due to the lack of information on abundance, distribution, and stock structure, and the climate-related habitat changes already seen to be taking place in the waters south of this area (NAMMCO 2018).

WEST GREENLAND

Narwhals that summer in West Greenland are from the Inglefield Bredning and Melville Bay stocks.

The Inglefield Bredning stock is considered to be depleted from its previous abundance, but has been stable since the 1980s (Witting 2016). With the stable abundance and sustainable harvest levels, there is currently low concern for this stock (NAMMCO 2018).

The Melville Bay stock is apparently stable, but is considered to be a small stock for which the current harvest levels exceed the recommendations of the NAMMCO-JCNB Joint Working Group. Therefore, the GROM expressed high concern for this stock (NAMMCO 2017, 2018).

Narwhals that occur in West Greenland during the autumn, winter, and spring are likely from a mix of stocks that include Inglefield Bredning and Melville Bay, but also narwhals that are from the summer aggregations/stocks from Canada (see below).

CANADIAN STOCKS

There are seven stocks of narwhals that summer in Canada, six of which are “shared stocks” with Greenland (i.e., they may migrate into Greenlandic waters and are available to Greenlandic hunters at some point during the year).

Somerset Island, Jones Sound and Smith Sound stocks

The Somerset Island stock is the largest narwhal stock and appears to be increasing. This stock is hunted by multiple communities in Canada and also in Greenland during the migration, but the removals are considered sustainable. Given these factors, there is low concern for this stock (NAMMCO 2018).

The Jones Sound and Smith Sound narwhal stocks are fairly large (about 12,000 and 16,000, respectively), removal numbers are low and sustainable, and there are few habitat concerns. Therefore, there is low concern for both of these stocks (NAMMCO 2018).

Admiralty Inlet and Eclipse Sound stocks

The Admiralty Inlet stock is fairly large and stable, and the hunt is considered sustainable. Although there are habitat concerns related to increasing human activities (including disturbance from freighters, cruise ships, and supply vessels) in their summer habitat, the GROM had low concern due to the size and sustainability of the hunts (NAMMCO 2018).

The Eclipse Sound stock appears to be stable at around 10,000 narwhals (although there is considerable uncertainty around the abundance estimate) and removals are considered sustainable. A major and growing concern is ship traffic related to the Baffinland–Mary River iron mine and tourism. Overall, the Eclipse Sound stock of narwhals was deemed to be of moderate concern (NAMMCO 2018).

Eastern Baffin Island and Northern Hudson Bay stocks

The Eastern Baffin Island stock is fairly large and removals relatively low. However, there is moderate concern for the stock due the lack of data on movements and stock structure, and the possibility that several stocks may inhabit the region in summer (NAMMCO 2018).

The Northern Hudson Bay stock of narwhals is separated from the other stocks in both summer and winter. This is the only narwhal stock in Canada that is not shared with Greenland. This is a fairly large stock of around 12,500 animals and the current level of hunting removals is considered sustainable. Although the loss of sea ice and concomitant increases in shipping and other industrial activities are of concern, overall concern for this stock is low (NAMMCO 2018).

STATUS ACCORDING TO OTHER ORGANISATIONS

Narwhals are currently listed on Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) (as are all species of cetaceans not listed on Appendix I). CITES is a legally-binding multilateral environmental agreement that aims to ensure that international trade does not threaten the survival of species in the wild. Both Denmark (Greenland) and Norway are signatories to the convention. A listing on Appendix II means that an export permit shall only be granted when the Scientific Authority of the State of export has advised that such export will not be detrimental to the survival of the species in the wild.

On the IUCN “Red list” narwhals are listed as Least Concern in an assessment made in 2017.

Management

Narwhals inhabit the waters of two NAMMCO member states: Norway and Greenland.

Norway

Norway does not presently permit the catch of narwhals in its territory.

Greenland

Some West Greenland narwhals may travel to Canadian waters, therefore management is a shared responsibility between Greenland and Canada. Greenland and Canada have established a bilateral management body, the Canada/Greenland Joint Commission on the Conservation and Management of Narwhal and Beluga (JCNB). The JCNB has a Joint Scientific Working Group (JWG) together with the NAMMCO Scientific Committee Working Group on the Population Status of Narwhal and Beluga in the North Atlantic. This NAMMCO-JCNB JWG provides advice at the request of the JCNB and NAMMCO, pertaining to such issues as stock delineation, total allowable catches and threats to beluga and narwhal populations. The JCNB Commission meets periodically to receive this advice and provide management advice to Canada and Greenland.

Regulations and Requirements

Quotas for narwhals were introduced in 2004 for West Greenland and in 2008 for East Greenland (Nielsen and Meilby 2013). A license for the species and period is required in order to hunt narwhal, in addition to a hunting permit. There is no narwhal hunting permitted in the national park in Northeast Greenland. The Ministry of Fisheries, Hunting and Agriculture is responsible for regulating narwhal whaling in Greenland. Regulations govern the seasons in which narwhals can be hunted and the weapons and equipment that may be used. Successful whale hunts must be reported to municipal authorities to facilitate monitoring of the hunt. Compliance with quotas and other regulations is monitored by wildlife officers at the local level.

WEST GREENLAND

Assessment of sustainable catch levels for West Greenland were provided in JCNB/NAMMCO JWG report 2021.

Melville Bay

Assessment of sustainable catch levels for West Greenland were provided in JCNB/NAMMCO JWG report 2021.

Melville Bay

For the stock of narwhals summering in Melville Bay there are four aerial surveys that provided absolute stock estimates, the last of which is from 2019. It is estimated that the population has been reduced from 2,910 (90% CI: 1,710-4,890) narwhals in 1970 to 1,250 (90% CI: 420-2,730) in 2022. This decline began specifically to increase after 1990 where the annual catches including losses increased from less than 100 to around 200 at the turn of the millennium. Today, the population, like the three populations in East Greenland, has been greatly reduced, likely to approximately 25% of its original size.

Inglefield Bredning

The narwhal population in Inglefield Bredning is the largest summer population in Greenland. There are six absolute estimates from aerial surveys in the period from 1985 to 2019. In comparison with the four other huntable stocks of narwhals in Greenland, there is for Inglefield Bredning a better balance between the size of the hunt and the production in the stock. This has meant a smaller and relatively even decline from an estimate of 4,540 (90% CI: 3,440-6,540) narwhals in 1970 to 2,630 (90% CI: 1,640-3,940) in 2022. Where today there is only approximately 40% left of the 1970 stock in Melville Bay, there is approximately 60% left of the 1970 stock in Inglefield Bredning.

The advice from NAMMCO SC in 2022 suggests that 55 narwhals can be hunted annually in Inglefield Bredning and that a harvest at that magnitude will allow the population to increase at a probability of 70%.

EAST GREENLAND

In 2019 and 2023 the Ad Hoc Working Group on Narwhal in East Greenland (NAMMCO 2019a, NAMMCO 2023) expressed concerns regarding a small and declining population experiencing an ongoing harvest and significant habitat changes. On the basis of this, the NAMMCO Scientific Committee recommended there be an immediate reduction to 0 catches in all three management areas of East Greenland, at least until new abundance estimates are generated (NAMMCO 2019b, NAMMCO 2024a). This recommendation was stressed by the NAMMCO Scientific Committee in 2022 and 2024, due to an imminent risk of near-term extirpation of the stocks. At its meeting in 2024, the NAMMCO Management Committee for Cetaceans put forward a recommendation to Greenland, urging for the implementation of a management approach that will reduce narwhal (and beluga) quotas to zero (NAMMCO 2024b).

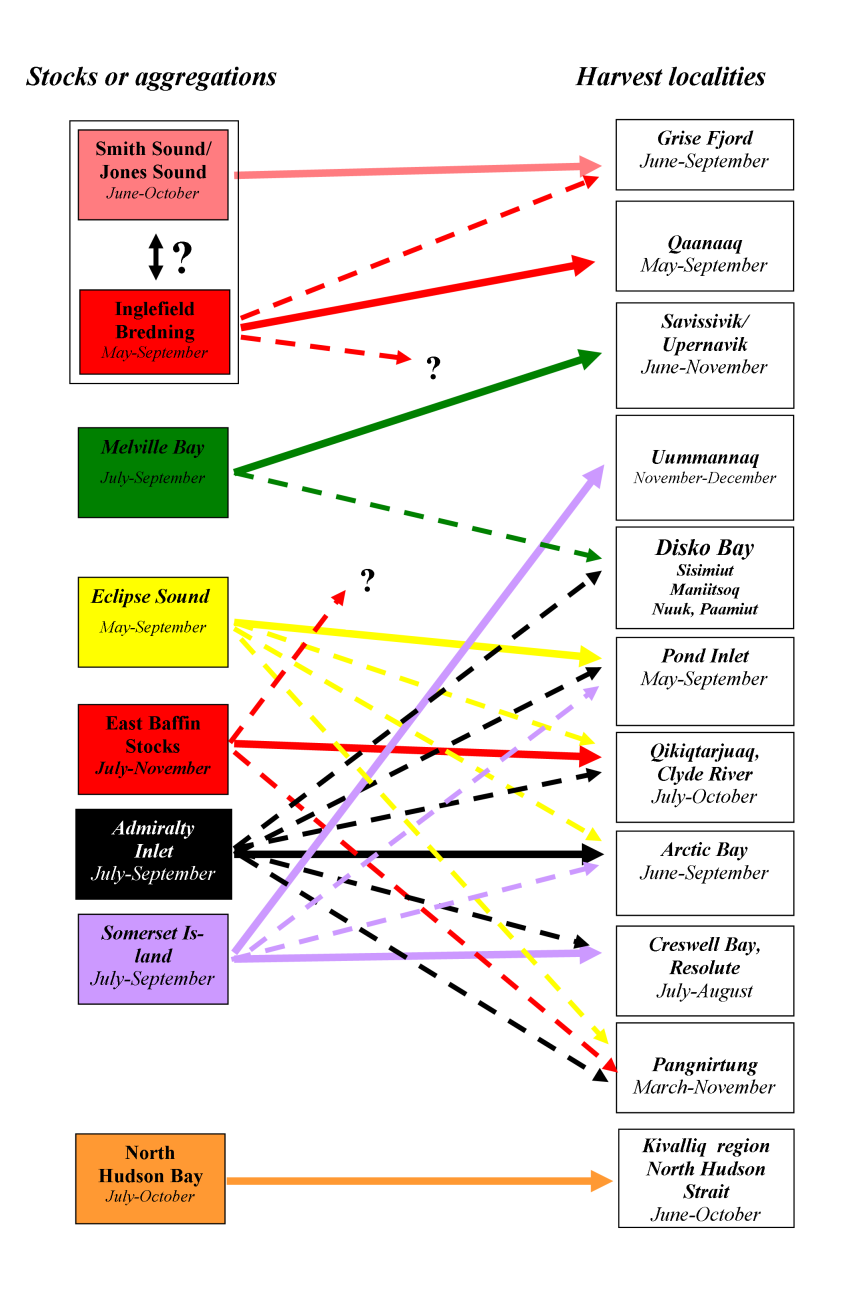

Catch allocation model for shared stocks

Managing a shared stock between two countries can be challenging, especially when that stock of animals migrates. The main problem is how to identify which stock the hunters are taking in various areas in different seasons. The NAMMCO-JCNB Joint Scientific Working Group has developed a model that allows managers to assign catches from the narwhal metapopulation that is shared by Canada and Greenland to the appropriate summering aggregation, by different hunting grounds and seasons (Watt et al. 2019, Witting et al. 2019). The model includes all information that is available on narwhal movements including telemetry data, all abundance estimates, seasonal occurrence and historical catch data (see examples of the types of information used below). This model is a good example of how management of migratory species shared by two or more countries can be developed. From the catch allocation model’s analysis of all satellite tracking, stock estimates and their uncertainties, it is estimated that about 10% and 20% of the narwhals caught in Uummannaq and Disko Bay may come from the stock in Melville Bay. There is therefore a negative correlation between the sustainable catch in these areas, where catch in Upernavik/Savissivik must be matched by a reduction in Uummannaq and Disko Bay if the total catch is to be sustainable. This means that if you catch 1 whale less in Upernavik/Savissivik, then you can catch approx. 5 whales extra in Uummannaq, and approx. 2.5 extra whales in Disko Bay.

For the total catch of narwhals in West Greenland to be optimised, zero whales must be caught in Upernavik/Savissivik in order to be able to catch 123 and 54 narwhals per year in Uummannaq and Disko Bay. In this case, one can sustainably catch 229 narwhals per year in West Greenland, the majority of which (i.e., 150) come from summer populations in Eastern Canada.

If, on the other hand, it is desirable to maintain the largest possible sustainable catch in Upernavik/Savissivik (i.e., 24 narwhals per year) then it is not possible to catch narwhals in Uummannaq and Disko Bay if the catch is to be sustainable. In this case, only 79 narwhals per year can be caught in West Greenland, none of which come from the summer populations in Eastern Canada.

Management in Canada

Canada sets harvest levels for narwhals using a “Precautionary Approach Framework” (DFO 2008), which takes a conservative approach to management. As part of this approach, the Potential Biological Removal (PBR) method is used to determine the Total Allowable Harvest. This method was developed in the United States for the regulation of human-induced mortality on marine mammals, and produces a single threshold value for removals from a population, which allows depleted stocks to grow and other stocks to maintain their numbers.

The method produces a total allowable landed catch (TALC) for a narwhal stock, which takes into account whales that are struck and lost by hunters. Hunt loss corrections are derived from annual reports of landed and lost whales from communities under Community Based Management (DFO 2008).

UTILISATION

Narwhals have long been a staple food resource for indigenous peoples throughout the Arctic and continue to be an important part of northern diets today. The skin and attached subcutaneous fat is considered a delicacy called mattak (various spellings and pronunciations, including maktaaq and muktuk). The meat varies in quality depending on the cut and is eaten raw, dried or cooked, or used as dog food.

Narwhal meat, organs and skin are sewn into bundles then buried in gravel for several months. © J. Blair Dunn, Fisheries and Oceans Canada.

Sometimes the meat and mattak are aged and prepared in specific ways to make traditional delicacies. The flippers, organs and intestines are also used as food. The skin from the top part of the whale can be cut and prepared to make rope, and the tendons have been used to make sinew for sewing. The blubber can be rendered to oil and used in traditional lamps (qulliq) as a source of light and heat. Even the bones have been used as a food source, construction material and for carving. While many of these uses have been replaced by modern materials, narwhal mattak and meat are still an important part of the diet in some areas of Arctic Canada and Greenland.

Although narwhals contribute only about 5–6% of the total meat supply in East Greenland, their economic and cultural value remains high. Mattak, in particular, is a valued delicacy and is often the main driver of hunting rather than meat needs. The retail price for mattak has increased exponentially from 50 kr/kg in 1982 to 500 kr/kg in 2020 in Greenland. The high market demand for mattak means that narwhals are among the most valuable wildlife products in Greenland (Heide-Jørgensen et al., 2025).

Share of catch

Cutting mattak with an Ulu © Lola Akinmade Åkerström, Visit Greenland

Historically, the catch of narwhals or other large animals was divided and shared among participating hunters and their extended families according to complex traditional rules (Inuktitut ningiqtuq, Greenlandic ningerpoq). This helped to ensure that the entire camp or community received a portion of the catch (Wenzel 1995). More recently, the regulation of narwhal hunting and changing hunting methods and equipment have led to changes in the sharing system (Sejersen 2001). In Greenland particularly, part of the catch is sold in super markets and open-air markets (Greenlandic Kalaalimineerniarfik, Danish brædtet). This provides a welcome source of income for hunters and a way for non-hunters to access wild country foods.

HUNTING

Hunting occurs during the open water season from boats and from the floe edge during the fall, winter, and spring. The timing of the hunt depends on the weather, the nature of the ice, and the movements of the narwhals. The timing of each of these depends on location. For example, Arctic Bay generally has a shorter hunting period (June–September) than Pangnirtung, which may run from March to November (Heide-Jørgensen et al. 2013b).

In West Greenland, in the Upernavik, Uummanaaq, and Disko Bay areas, hunting generally occurs during the fall and winter (NAMMCO 2013). In the far north of West Greenland, hunters from Qaanaaq sometimes see narwhals in the Smith Sound area in winter and spring (January–June). However, most hunting takes place between May and September, with peaks in the months of July and August (Heide-Jørgensen et al. 2013b).

In East Greenland, the majority of the harvest occurs during the summer months (Garde et al. 2019). As with other stocks, the timing of the hunt depends on the movement of the narwhals.

Methods

The following descriptions of hunting methods in Canada and Greenland were taken from the NAMMCO Expert Group Meeting to Assess the Hunting Methods for Small Cetaceans, held in 2011 (NAMMCO, 2012):

Small whale hunting Greenland © P. Hegelund

In West Greenland and Canada, narwhals are hunted during the spring, summer, and fall from small boats, or at the ice edge or at ice cracks. The kayak is still used for hunting in some areas of Northwest Greenland. In this type of hunting, the animal is approached quietly by one or two kayaks and the hunter uses a hand-held harpoon with a detachable head (Greenlandic: tuukaak). The harpoon head is attached by a line to a float (Greenlandic: quataq), which is then used as a drag or brake (Greenlandic: miutak) to slow the wounded animal. The hunter then shoots the whale with a high-powered rifle when it resurfaces. Having the float attached before shooting minimises the risk that the animal is struck but lost by the hunter.

Similar hunting methods are used from small motor boats and from the ice in Greenland and Canada. Ideally, the whale is harpooned first to secure it; it is thereafter dispatched using a rifle. The harpoon strike alone is, in some cases, sufficient to kill the animal. In other cases, the narwhal is shot first to wound it and slow it down so it can be secured using a harpoon and line.

Nets are sometimes used to capture narwhals in East Greenland. The narwhal swims into the net, becomes entangled, and will drown if it cannot surface. If they remain alive, they are shot by the hunter when the net is checked.

Catches in NAMMCO member countries since 1992

| Country | Species (common name) | Species (scientific name) | Year or Season | Area or Stock | Catch Total | Quota (if applicable) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2009/2010 | Inglefield Bredning | 63 | 85 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2009/2010 | Melville Bay | 96 | 81 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2009/2010 | West | 139 | 144 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2009/2010 | East | 12 | 85 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2009/2010 | Total | 310 | 395 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2008/2009 | Inglefield Bredning | 115 | 90 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2008/2009 | West | 267 | 320 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2008/2009 | East | 76 | No quota |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2008/2009 | Total | 458 | 410 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2007/2008 | Inglefield Bredning | 106 | 85 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2007/2008 | West | 227 | 215 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2007/2008 | East | 15 | No quota |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2007/2008 | Total | 348 | 300 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2006/2007 | Inglefield Bredning | 72 | 70 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2006/2007 | West | 209 | 247 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2006/2007 | East | 40 | No quota |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2006/2007 | Total | 321 | 317 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2005/2006 | Inglefield Bredning | 99 | 100 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2005/2006 | West | 291 | 200 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2005/2006 | East | 8 | No quota |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2005/2006 | Total | 398 | 300 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2004/2005 | Inglefield Bredning | 0 | 100 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2004/2005 | West | 45 | 200 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2004/2005 | East | N/A | No quota |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2004/2005 | Total | 45 | 300 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2023 | Total | 599 | 683 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2023 | Zone 1 - Etah | 0 | 10 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2023 | Zone 2 - Qaanaaq | 132 | 128 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2023 | Zone 3 - Melville Bugt | 173 | 128 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2023 | Zone 4 - Uummannaq | 132 | 209 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2023 | Zone 5 - Disko bugt | 121 | 147 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2023 | Zone 6 - Tasiilaq | 5 | 21 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2023 | Zone 7 - Ittoqqortoormiit | 11 | 20 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2023 | Zone 8 - kangerlussuaq | 25 | 20 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2022 | Total | 527 | 771 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2022 | Zone 1 - Etah | 0 | 10 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2022 | Zone 2 - Qaanaaq | 78 | 107 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2022 | Zone 3 - Melville Bugt | 85 | 117 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2022 | Zone 4 - Uummannaq | 220 | 305 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2022 | Zone 5 - Disko bugt | 80 | 157 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2022 | Zone 6 - Tasiilaq | 4 | 15 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2022 | Zone 7 - Ittoqqortoormiit | 45 | 45 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2022 | Zone 8 - kangerlussuaq | 15 | 15 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2021 | Total | 419 | 547 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2021 | Zone 1 - Etah | 3 | 6 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2021 | Zone 2 - Qaanaaq | 91 | 98 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2021 | Zone 3 - Melville Bugt | 70 | 70 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2021 | Zone 4 - Uummannaq | 143 | 154 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2021 | Zone 5 - Disko bugt | 92 | 173 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2021 | Zone 6 - Tasiilaq | 7 | 7 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2021 | Zone 7 - Ittoqqortoormiit | 2 | 29 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2021 | Zone 8 - kangerlussuaq | 11 | 10 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2021 | Zone 9 - Northeast Greenland | 0 | 0 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2020 | Zone 1 - Etah | 2 | 6 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2020 | Zone 2 - Qaanaaq | 91 | 93 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2020 | Zone 3 - Melville Bugt | 46 | 71 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2020 | Zone 4 - Uummannaq | 16 | 197 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2020 | Zone 5 - Disko bugt | 68 | 153 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2020 | Zone 6 - Tasiilaq | 22 | 12 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2020 | Zone 7 - Ittoqqortoormiit | 36 | 32 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2020 | Zone 8 - kangerlussuaq | 0 | 0 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2020 | Zone 9 - Northeast Greenland | 0 | 0 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2020 | Total | 281 | 564 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2019 | Inglefield Bredning | 150 | 152 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2019 | Melville Bay | 110 | 73 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2019 | West | 198 | 303 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2019 | East | 78 | 64 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2019 | Total | 536 | 592 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2018 | Inglefield Bredning | 52 | 98 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2018 | Melville Bay | 65 | 90 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2018 | West | 317 | 271 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2018 | East | 73 | 66 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2018 | Total | 507 | 530 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2017 | Inglefield Bredning | 108 | 103 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2017 | Melville Bay | 93 | 100 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2017 | West | 134 | 231 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2017 | East | 91 | 98 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2017 | Total | 426 | 532 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2016 | Inglefield Bredning | 81 | 103 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2016 | Melville Bay | 91 | 90 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2016 | West | 176 | 306 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2016 | East | 53 | 82 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2016 | Total | 401 | 581 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2015 | Inglefield Bredning | 75 | 85 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2015 | Melville Bay | 71 | 72 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2015 | West | 72 | 153 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2015 | East | 94 | 105 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2015 | Total | 312 | 415 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2014 | Inglefield Bredning | 102 | 85 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2014 | Melville Bay | 113 | 120 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2014 | West | 119 | 150 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2014 | East | 81 | 110 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2014 | Total | 415 | 465 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2013 | Inglefield Bredning | 83 | 85 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2013 | Melville Bay | 71 | 81 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2013 | West | 130 | 144 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2013 | East | 66 | 88 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2013 | Total | 350 | 398 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2012 | Inglefield Bredning | 131 | 85 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2012 | Melville Bay | 83 | 83 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2012 | West | 99 | 161 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2012 | East | 48 | 129 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2012 | Total | 361 | 458 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2011 | Inglefield Bredning | 55 | 85 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2011 | Melville Bay | 79 | 81 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2011 | West | 117 | 144 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2011 | East | 45 | 85 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2011 | Total | 296 | 395 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2010 | Inglefield Bredning | 89 | 85 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2010 | Melville Bay | 52 | 81 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2010 | West | 44 | 144 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2010 | East | 33 | 85 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2010 | Total | 218 | 395 |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2003 | West | 666 | No quota |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2003 | East | N/A | No quota |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2003 | Total | 666 | No quota |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2002 | West | 488 | No quota |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2002 | East | N/A | No quota |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2002 | Total | 488 | No quota |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2001 | West | 609 | No quota |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2001 | East | N/A | No quota |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2001 | Total | 609 | No quota |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2000 | West | 600 | No quota |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2000 | East | N/A | No quota |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 2000 | Total | 600 | No quota |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 1999 | Total | 912 | No quota |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 1998 | Total | 822 | No quota |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 1997 | Total | 797 | No quota |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 1996 | Total | 727 | No quota |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 1995 | Total | 461 | No quota |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 1994 | Total | 847 | No quota |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 1993 | Total | 741 | No quota |

| Greenland | Narwhal | Monodon monoceros | 1992 | Total | *No reported catches | No quota |

This database of reported catches is searchable, meaning you can filter the information by for instance country, species or area. It is also possible to sort it by the different columns, in ascending or descending order, by clicking the column you want to sort by and the associated arrows for the order. By default, 30 entries are shown, but this can be changed in the drop-down menu, where you can decide to show up to 100 entries per page.

Carry-over from previous years are included in the quota numbers, where applicable.

You can find the full catch database with all species here.

For any questions regarding the catch database, please contact the Secretariat at nammco-sec@nammco.no.

DIRECT AND INDIRECT IMPACTS OF CLIMATE CHANGE

Narwhals are endemic to the Arctic and depend on cold water. Their habitat range is therefore being restricted by the warming oceans as a result of climate change. Since they primarily get rid of heat through the dorsal ridge and tail fluke, their ability to adapt to these warming temperatures is also limited. While there have recently been several sightings of narwhals in areas north of their traditional range (e.g. Dove Bay), evidence suggests that a combination of hunting and climate change is negatively impacting the long-term viability of populations in Southeast Greenland.

Two major oceanographic changes linked to climate change have recently been observed in coastal areas of Southeast Greenland—a lack of pack ice in summer and increasing sea temperatures (NAMMCO 2019a). This has had cascading effects on the marine ecosystem, as observed through changed fish fauna and the presence of a large number of boreal cetaceans either new to the area or now occurring in surprisingly large numbers (e.g. humpback, fin, killer, and pilot whales, as well as white-beaked dolphins).

Another concern relating to changing sea ice cover is that loss of sea ice, particularly during the summer, may increase the access of killer whales to narwhals, thus increasing predation. Access to narwhals by man is also influenced by changes in sea ice concentration and extent. In Smith Sound, climate change has decreased spring and summer ice cover, which has enabled people in North Greenland to access the area and increase their catches (Nielsen 2009). The presence of open water is an important influence on the narwhal hunt, with the majority (72%) of the hunt in Nunavut taking place during the summer months (25th July–1st October) (White 2012).

Narwhals have also recently been moving further west in the Canadian Arctic, perhaps due to changes in sea ice cover, and they have been sighted and hunted near communities in the Central Canadian Arctic where they have seldom been seen before (White 2012).

Disturbances

Increasing industrial development in the Arctic, especially increased ship traffic, could also pose a threat to narwhal populations. Narwhals can detect the noise made by large icebreakers from at least 25 to 30 km away (Cosens and Dueck 1993). Other studies have found narwhals reacting to such noise at distances of 40–60 km (Finlay et al. 1990, Cosens and Dueck 1988, Tervo et al. 2021). Communities close to shipping routes in the Northwest Passage, Arctic Bay, and Pond Inlet report fewer narwhals in their areas than there have been in the past, and some hunters attribute this to increased ship traffic (White 2012). This is a concern, since vessel traffic is expected to increase as sea ice cover decreases with climate change.

Fisheries

Prior to 1996, there had been very little fishing in NAFO Division 0A, the waters on the Canadian side of Baffin Bay. Since 1998, the Greenland halibut fishery in this area has expanded. Currently, both otter trawls and gillnets are used in this fishery. As the fishery has expanded, concerns have been raised by both DFO and the Nunavut Wildlife Management Board that narwhals could be affected by removal of their primary prey species on their overwintering grounds, damage to bottom habitat by trawling, and entanglement in lost gillnets.

In order to mitigate these concerns, a number of measures were introduced. For example, an end date of 10th November was established for the gill net season, in an effort to reduce the risk of gear loss due to late season ice conditions. This date may be changed in response to seasonal conditions. Furthermore, starting in 2007, the southeast part of NAFO area 0A was closed to Greenland halibut fishing in order to protect this important food source for overwintering narwhals.

OIL AND GAS EXPLORATION